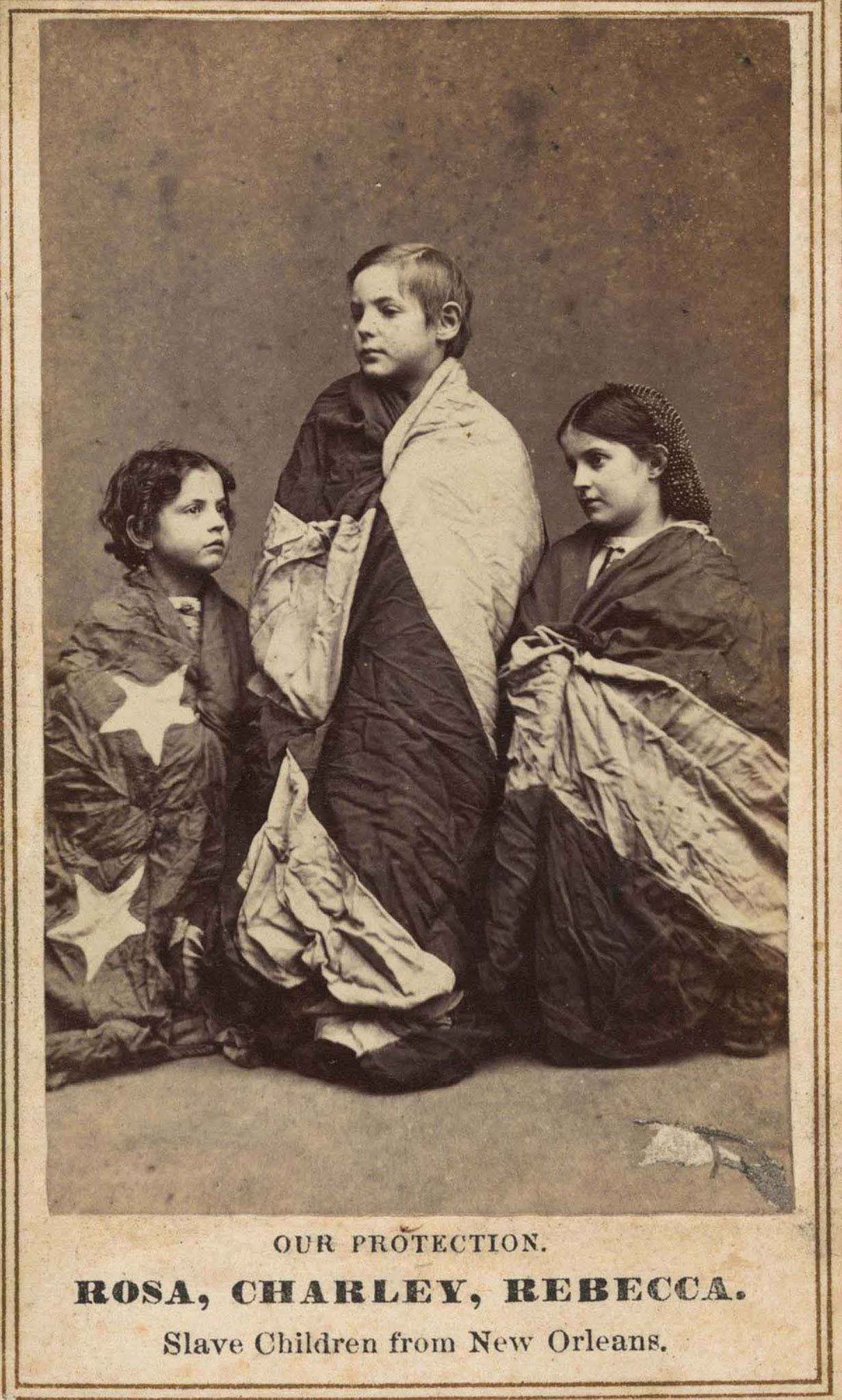

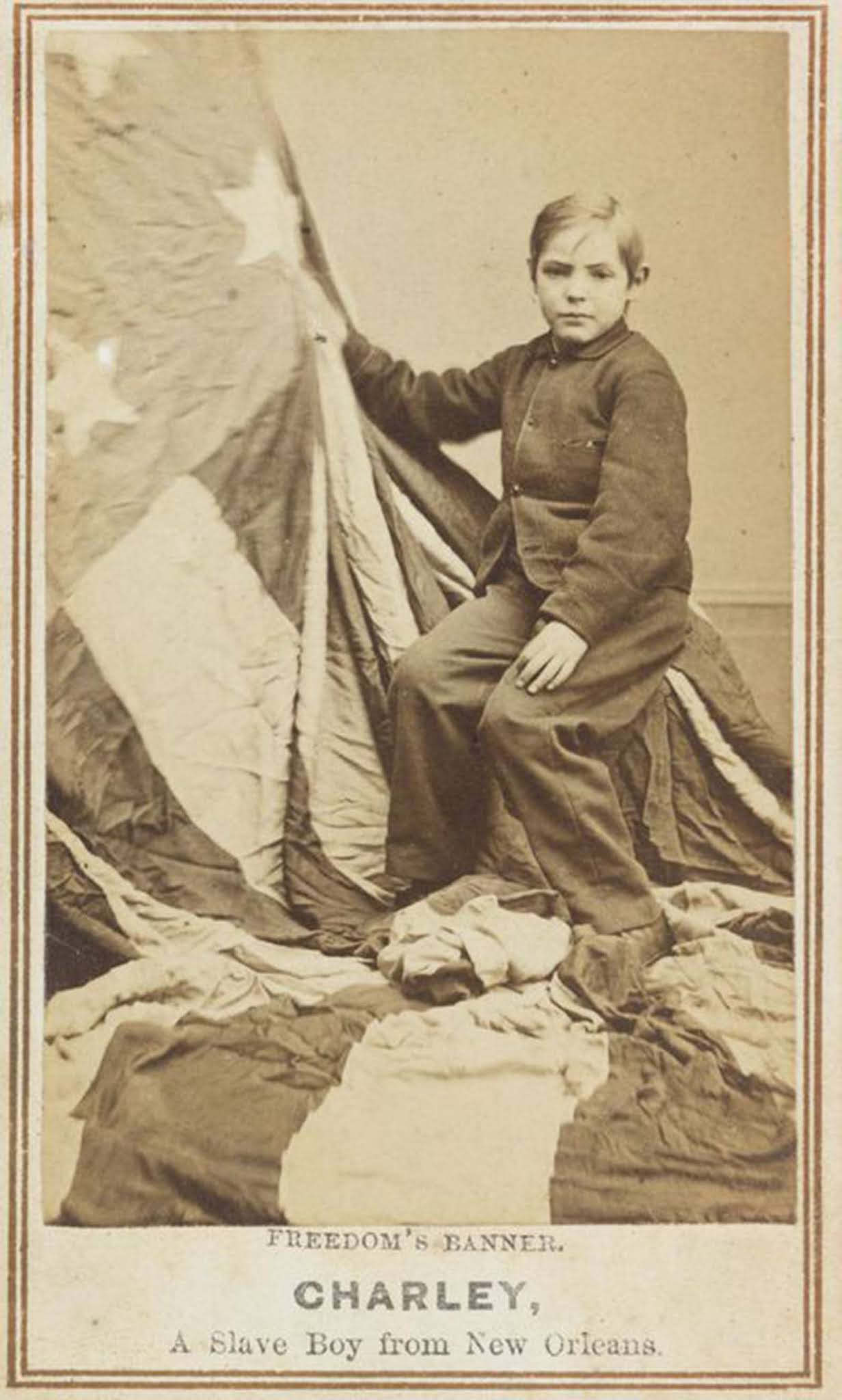

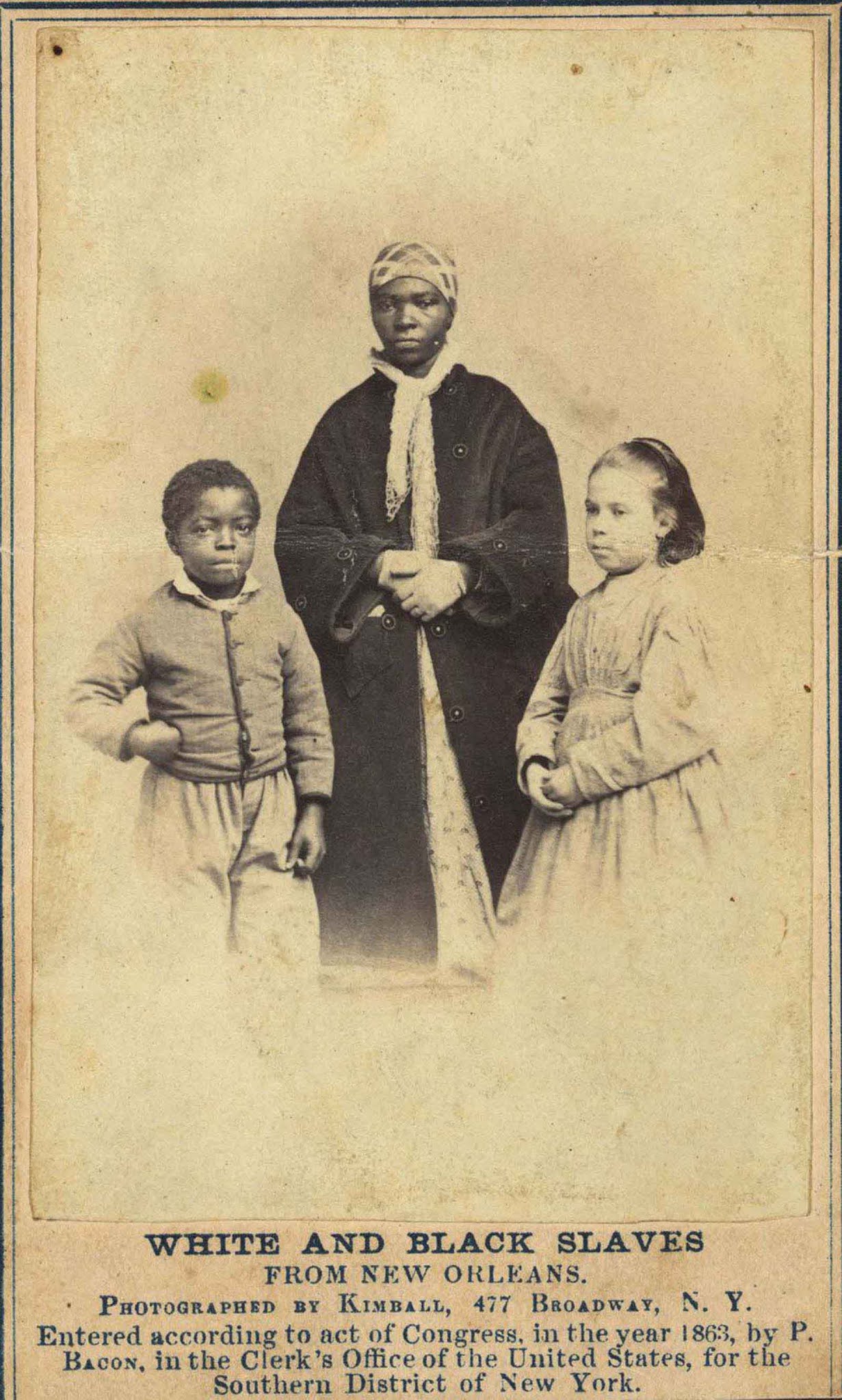

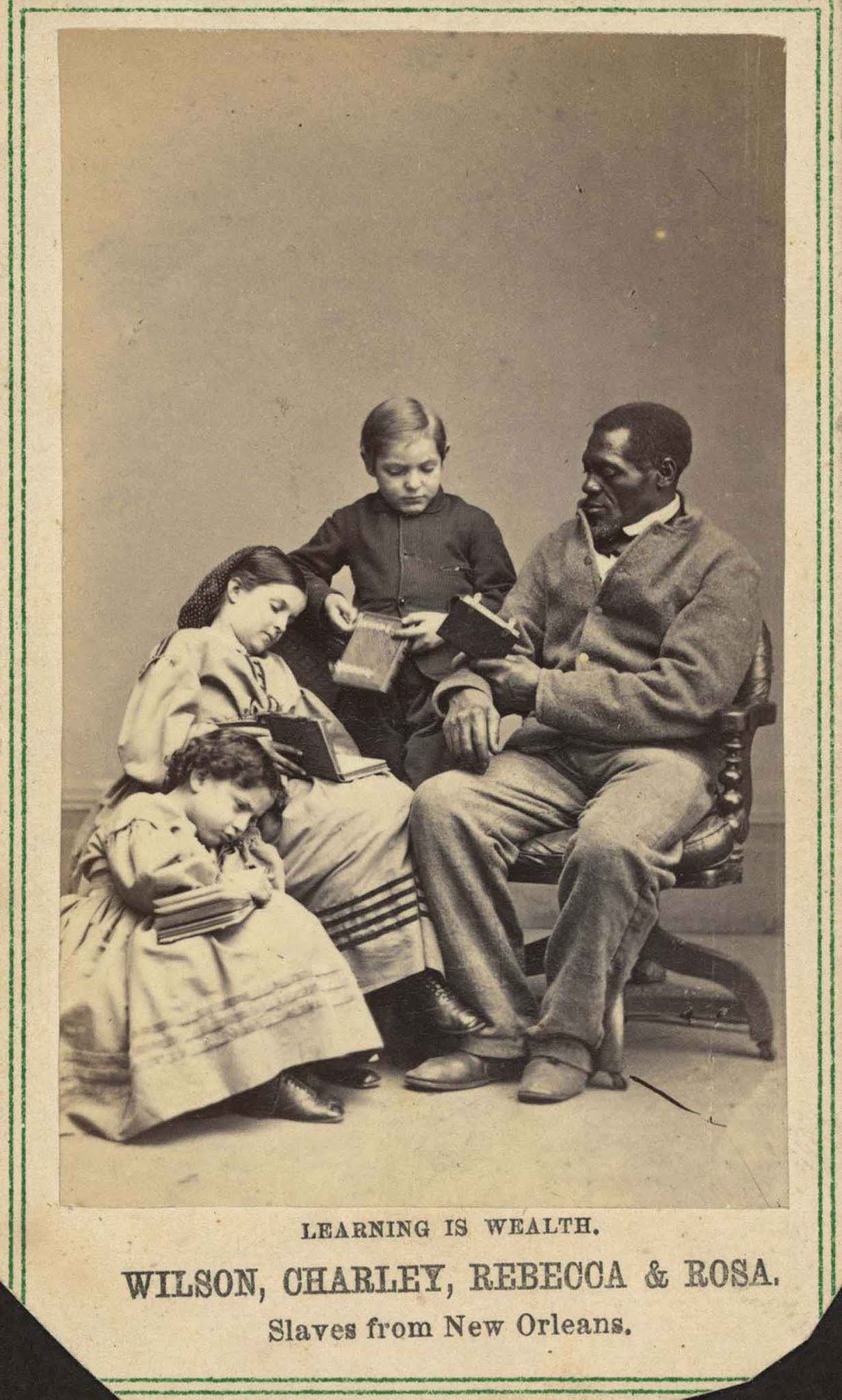

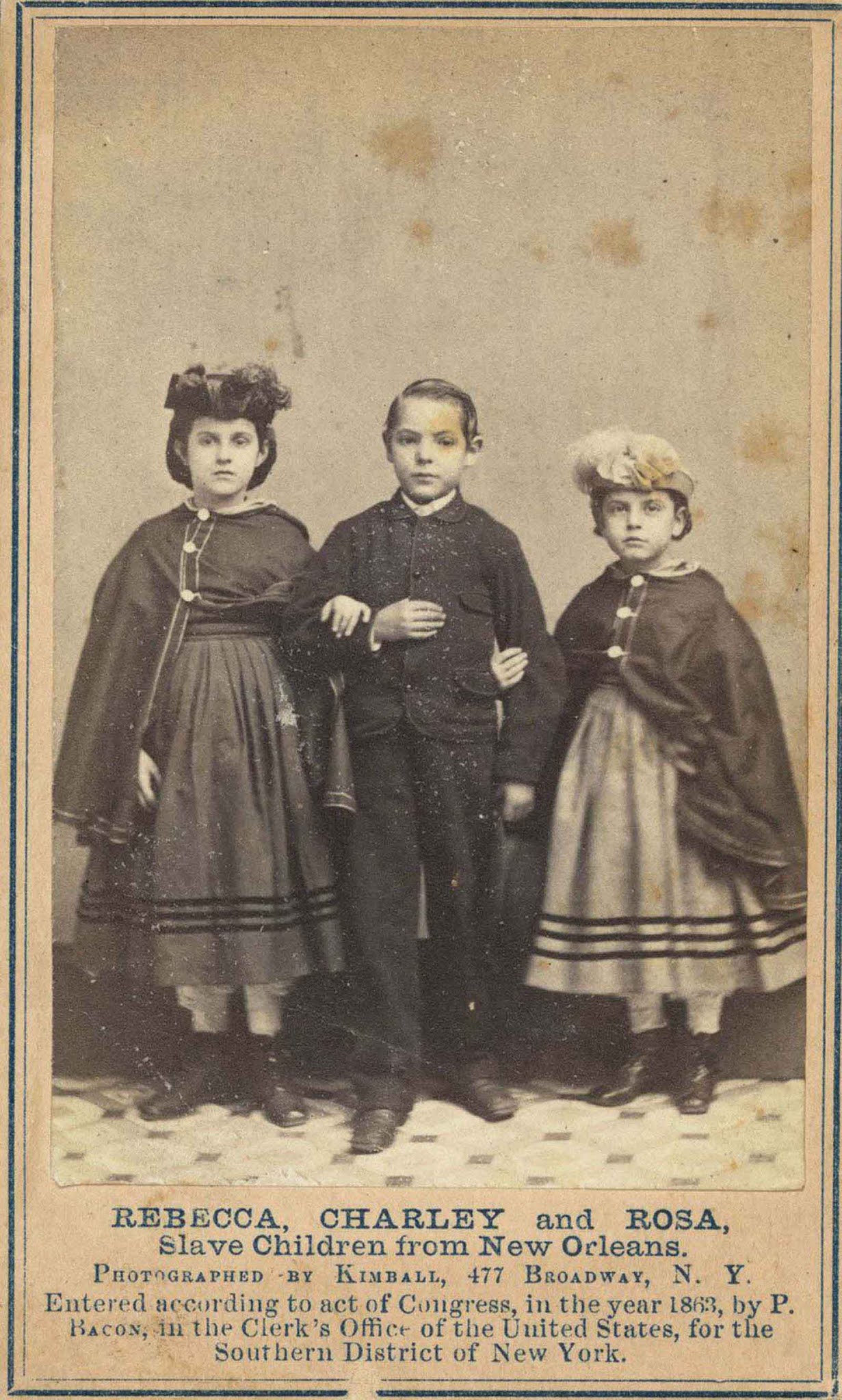

The children featured in these photographs drew attention to the fact that slavery was not solely a matter of color. If a child’s mother was a slave, then he or she was a slave as well. The images included children with predominantly European features photographed alongside dark-skinned adult slaves with typically African features. It was intended to shock the viewing audiences with a reminder that slaves shared their humanity, and evidence that slaves did not belong in the category of the “Other”. By disseminating images of seemingly white children, the campaign organizers alluded to the horrific conditions of slavery while creating a palatable image of emancipation for anxious audiences. These were not the lustful, violent slaves of planters’ nightmares, but rather docile, sentimentalized children and patient, pious adults. The pointed use of children naturalizes stereotypes of mixed-raced individuals. As historian Walter Johnson has described, frailty, delicacy, and submissiveness were all characteristics identified by slave traders and buyers as inherent to the special status and high value of light-skinned slaves on the slave market. These qualities could be read on the bodies of children without the artifice of costuming or attributes that an adult subject might have necessitated. At the same time, these images participated in the wider discourse of photography’s indexical relationship to nature and its ability to reveal the unseen. The pale bodies of these young children visualized miscegenation, which was and would continue to be a great source of anxiety in the wake of emancipation, but the effects of which had primarily been hidden from public scrutiny before the war. Moreover, through this campaign, miscegenation resulting in white slaves would be constructed as part of the history and not the future of a post-Civil War United States. With the end of slavery legally decreed, abolitionism would need to find a new cause to champion. Depicted as eager to learn, patriotic, and pious, these New Orleanian children would also be used to vindicate the much-maligned abolitionist movement, which had been considered a radical political third rail in the struggle to preserve the Union in the late 1850s. Of the “Emancipated Slaves from New Orleans” series, at least 22 different prints remain in existence today. The bulk was produced by New York photographers Charles Paxson, and Myron H. Kimball, who took the initial group portrait later reproduced as a woodcut in Harper’s Weekly. At least one CDV remains by Philadelphia photographer James E. McClees: a portrait of Rebecca. Transcript of the Harper’s Weekly article, January 30, 1864: Charles Taylor is eight years old. His complexion is very fair, his hair light and silky. Three out of five boys in any school in New York are darker than he. Yet this white boy, with his mother, as he declares, has been twice sold as a slave. First by his father and “owner,” Alexander Wethers, of Lewis County, Virginia, to a slave-trader named Harrison, who sold them to Mr. Thornhill of New Orleans. This man fled at the approach of our army, and his slaves were liberated by General Butler. The boy is decidedly intelligent, and though he has been at school less than a year he reads and writes very well. His mother is a mulatto; she had one daughter sold into Texas before she herself left Virginia, and one son who, she supposes, is with his father in Virginia. These three children, to all appearances of the unmixed white race, came to Philadelphia last December and were taken by their protector, Mr. Bacon, to the St. Lawrence Hotel on Chestnut Street. Within a few hours, Mr. Bacon informed me, he was notified by the landlord that they must therefore be colored persons, and he kept a hotel for white people. From this hospitable establishment, the children were taken to the “Continental,” where they were received without hesitation. Transcript of the Harper’s Weekly article, January 30, 1864: Rebecca Huger is eleven years old, and was a slave in her father’s house, the special attendant of a girl a little older than herself. To all appearance, she is perfectly white. Her complexion, hair, and features show not the slightest trace of African blood. In the few months during which she has been at school, she has learned to read well and writes as neatly as most children of her age. Her mother and grandmother live in New Orleans, where they support themselves comfortably by their own labor. The grandmother, an intelligent mulatto, told Mr. Bacon that she had “raised” a large family of children, but these are all that are left to her. Transcript of the Harper’s Weekly article, January 30, 1864: Rosina Downs is not quite seven years old. She is a fair child, with blonde complexion and silky hair. Her father is in the rebel army. She has one sister as white as herself and three brothers who are darker. Her mother, a bright mulatto, lives in New Orleans in a poor hut and has hard work to support her family. Transcript of the Harper’s Weekly article, January 30, 1864: Isaac White is a black boy of eight years, but none the less intelligent than his whiter companions. He has been in school about seven months, and I venture to say that not one boy in fifty would have made as much improvement in that space of time. Transcript of the Harper’s Weekly article, January 30, 1864: Wilson Chinn is about 60 years old, he was “raised” by Isaac Howard of Woodford County, Kentucky. When 21 years old he was taken down the river and sold to Volsey B. Marmillion, a sugar planter about 45 miles above New Orleans. This man was accustomed to brand his black slaves, and Wilson has on his forehead the letters “V. B. M.” Of the 210 slaves on this plantation 105 left at one time and came into the Union camp. Thirty of them had been branded like cattle with a hot iron, four of them on the forehead, and the others on the breast or arm. Transcript of the Harper’s Weekly article, January 30, 1864: Augusta Boujey is nine years old. Her mother, who is almost white, was owned by her half-brother, named Solamon, who still retains two of her children. (Photo credit: Library of Congress / Based on essays by Anjuli J. Lebowitz and Celia Caust-Ellenbogen). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe