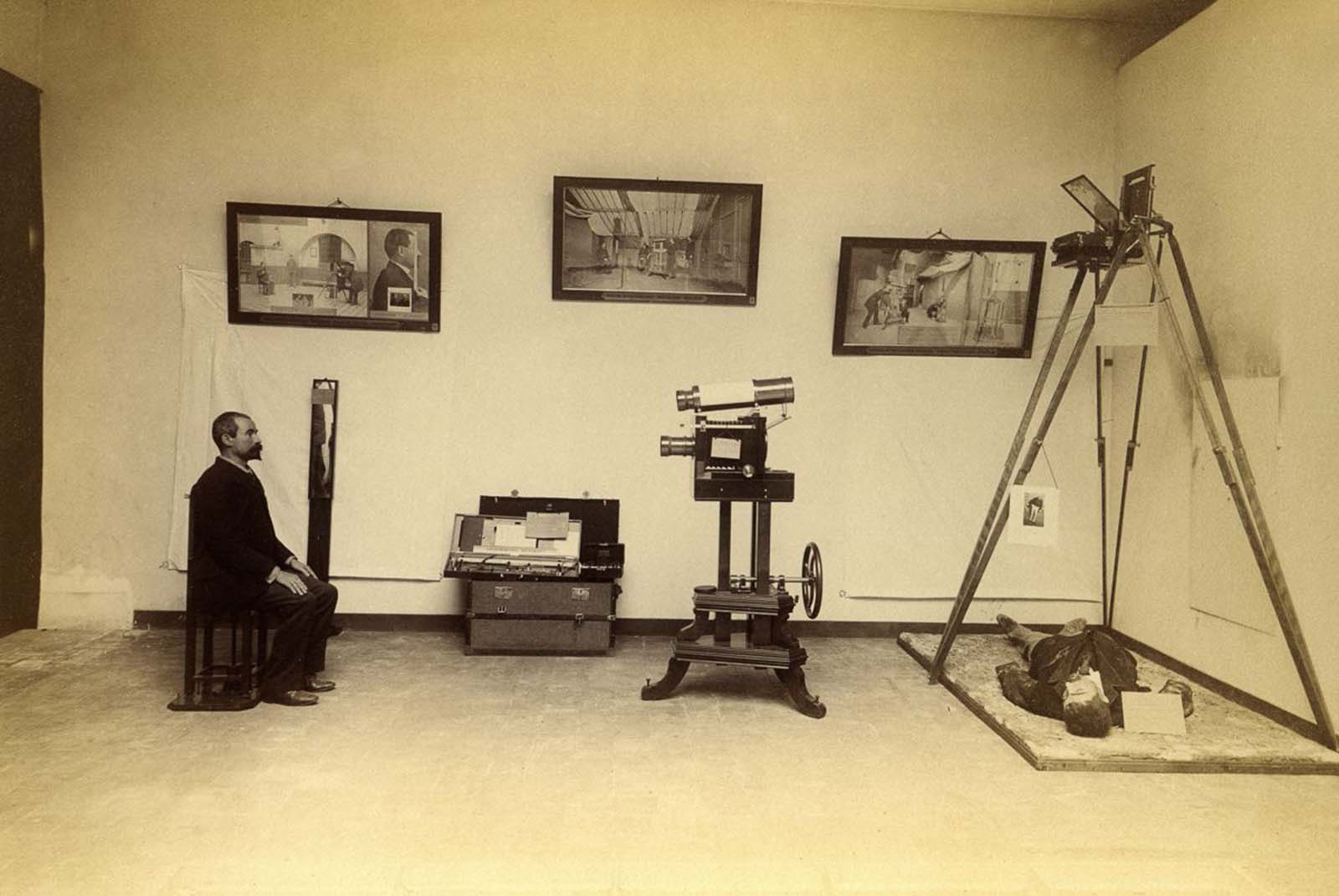

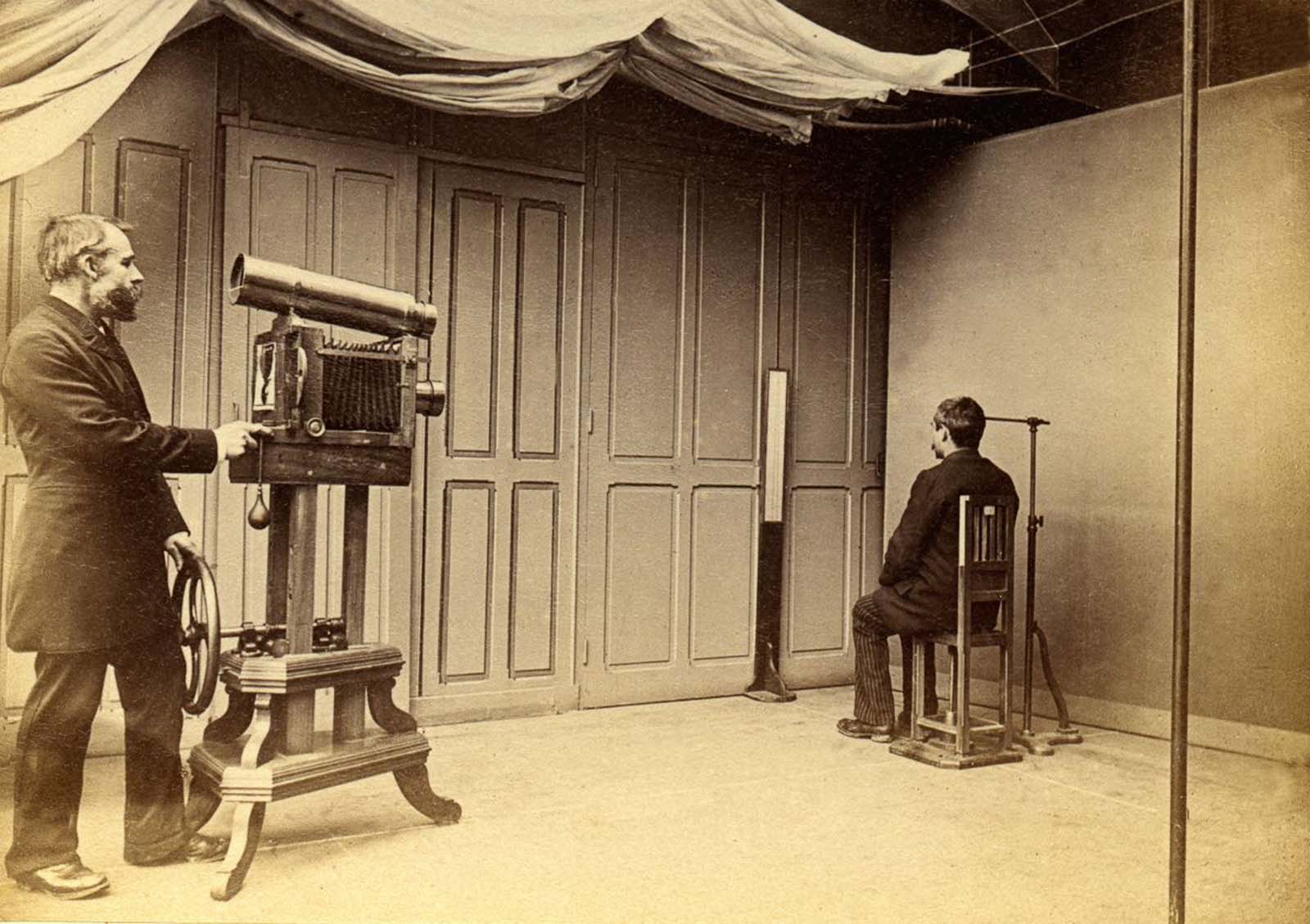

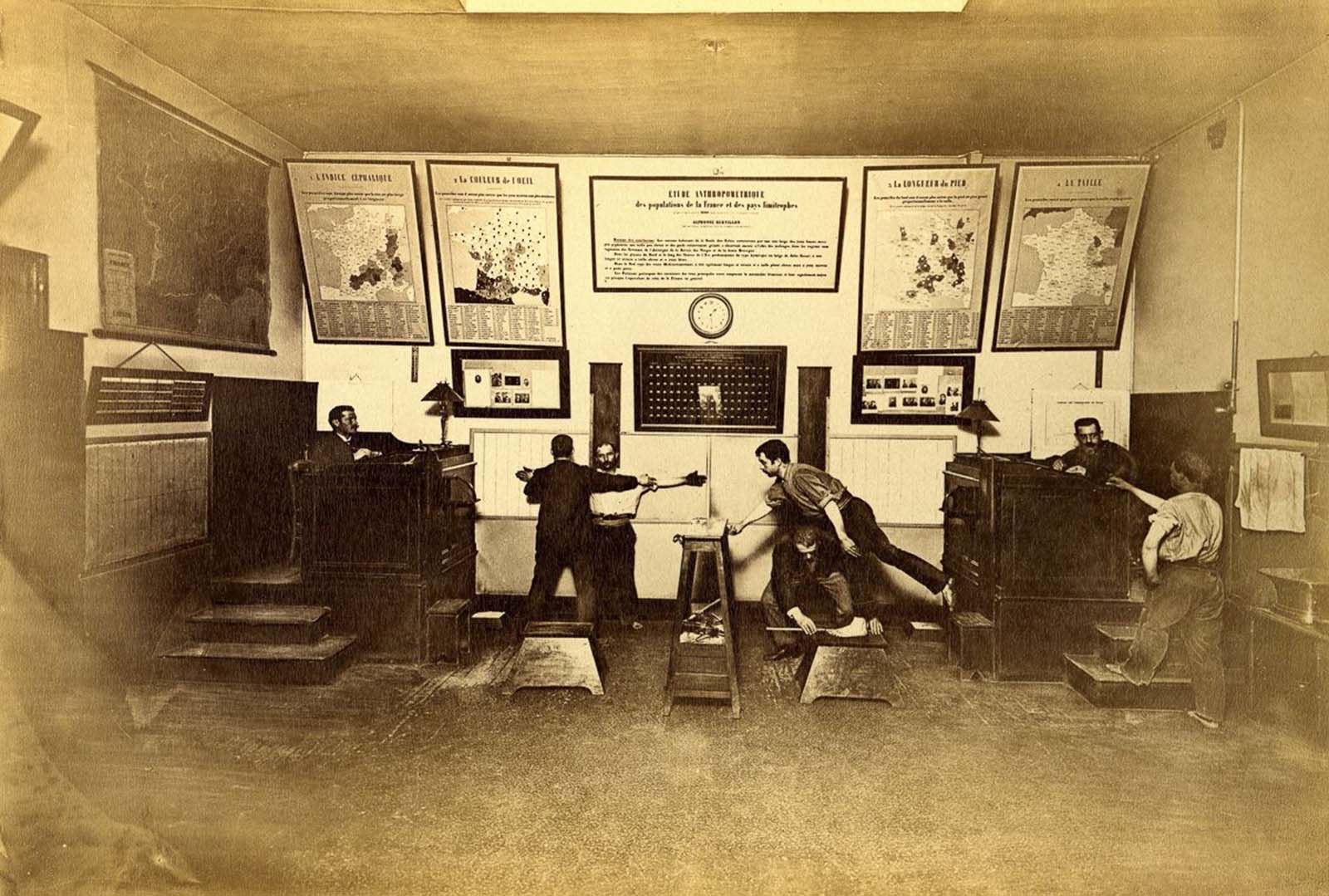

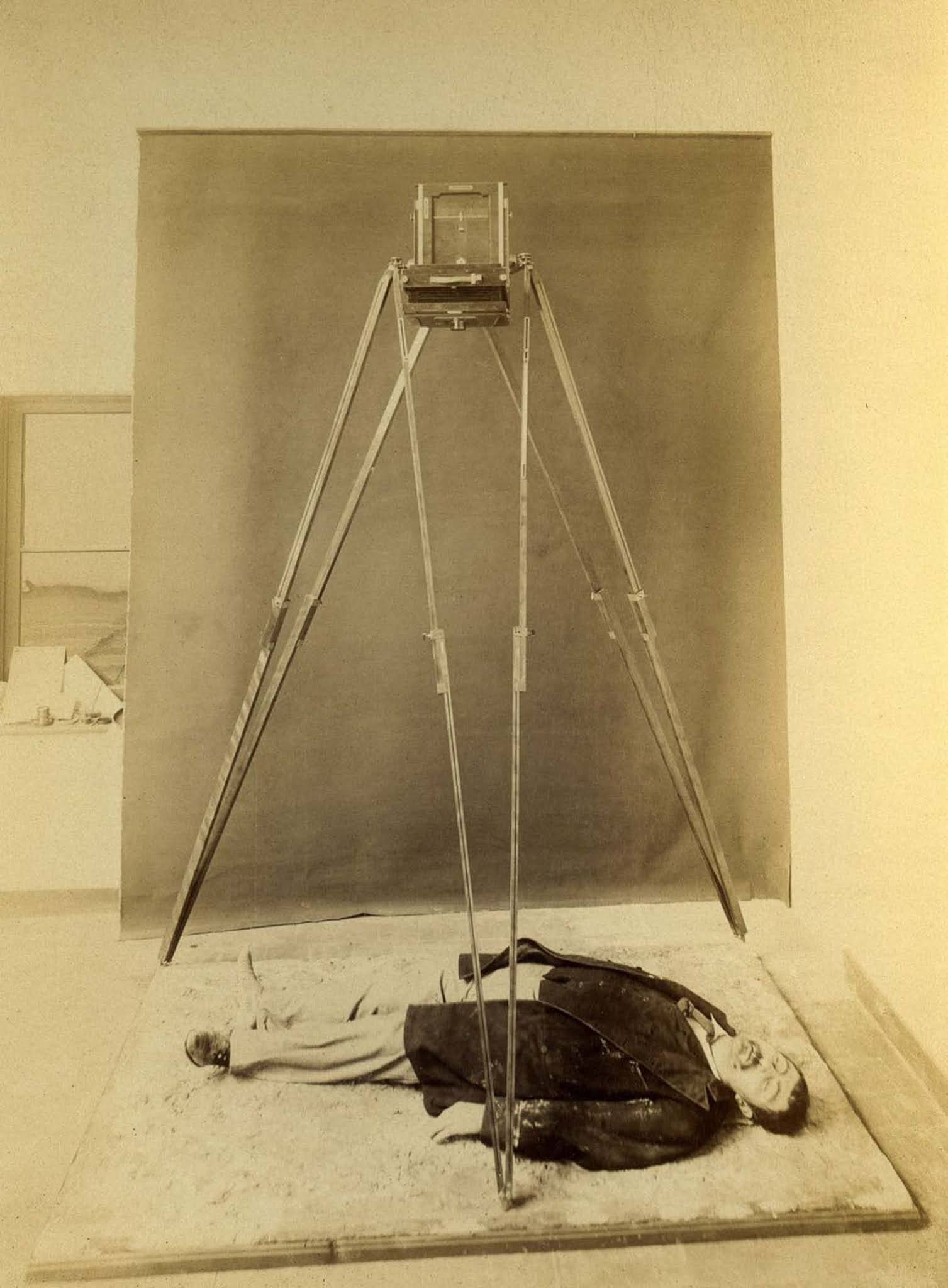

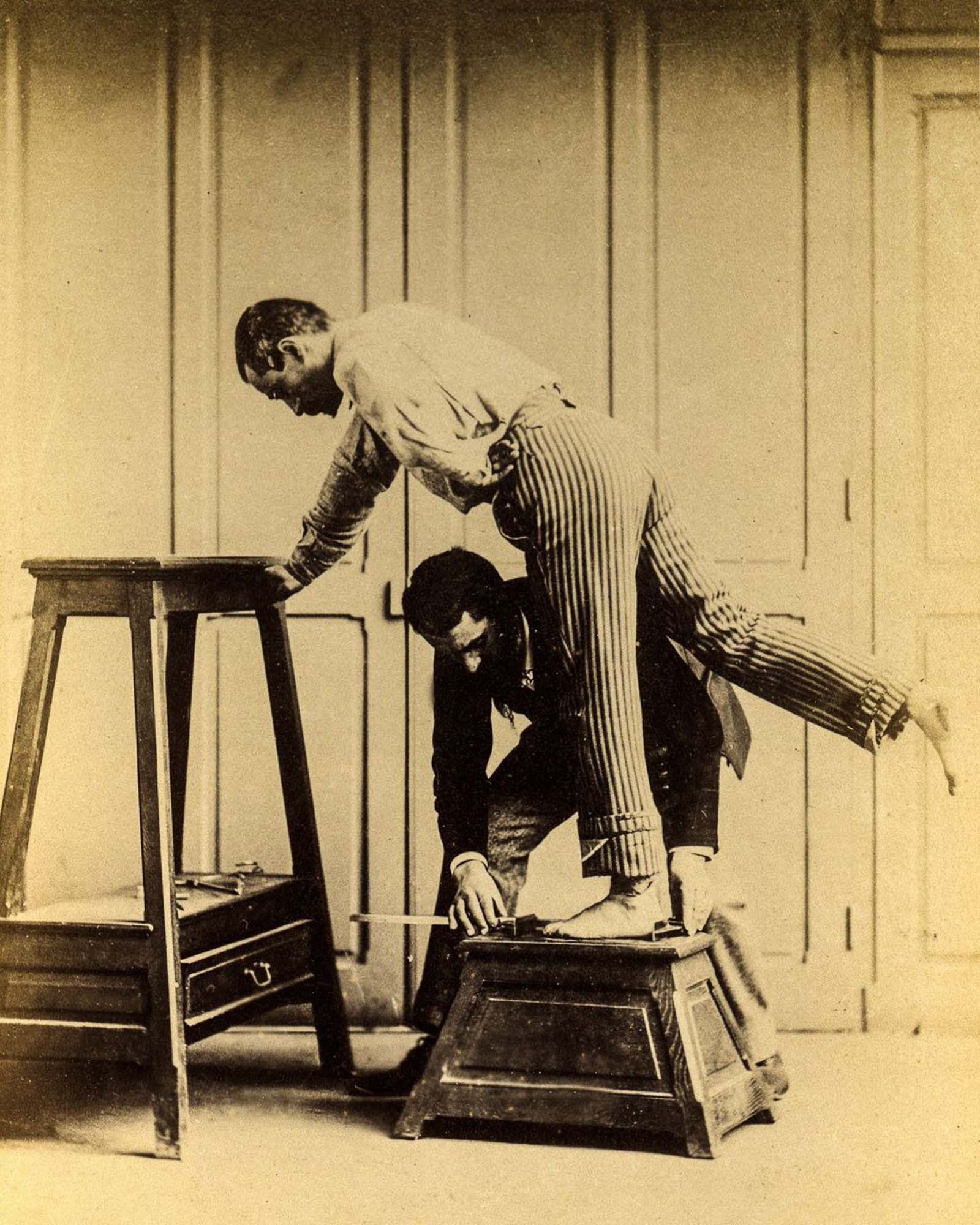

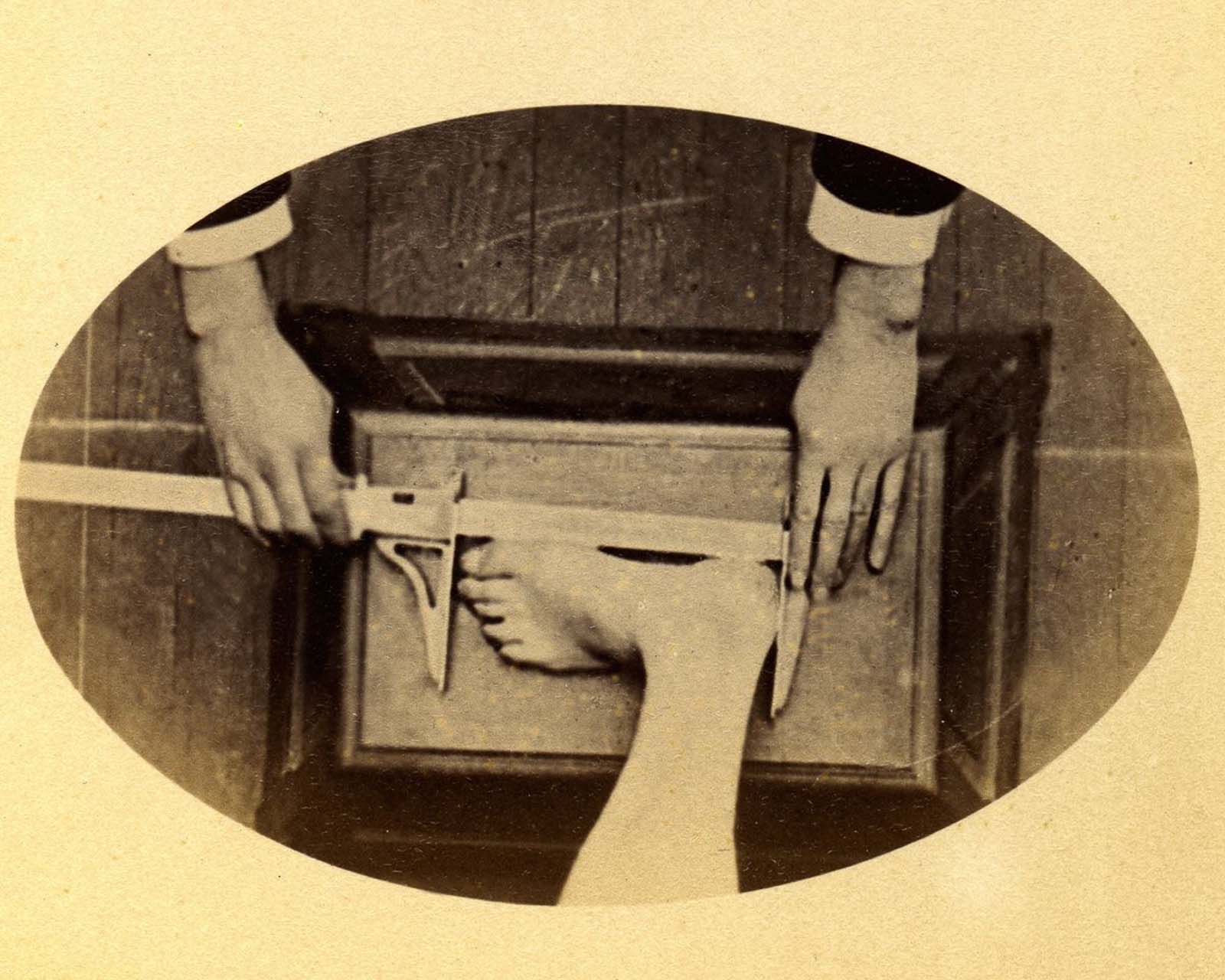

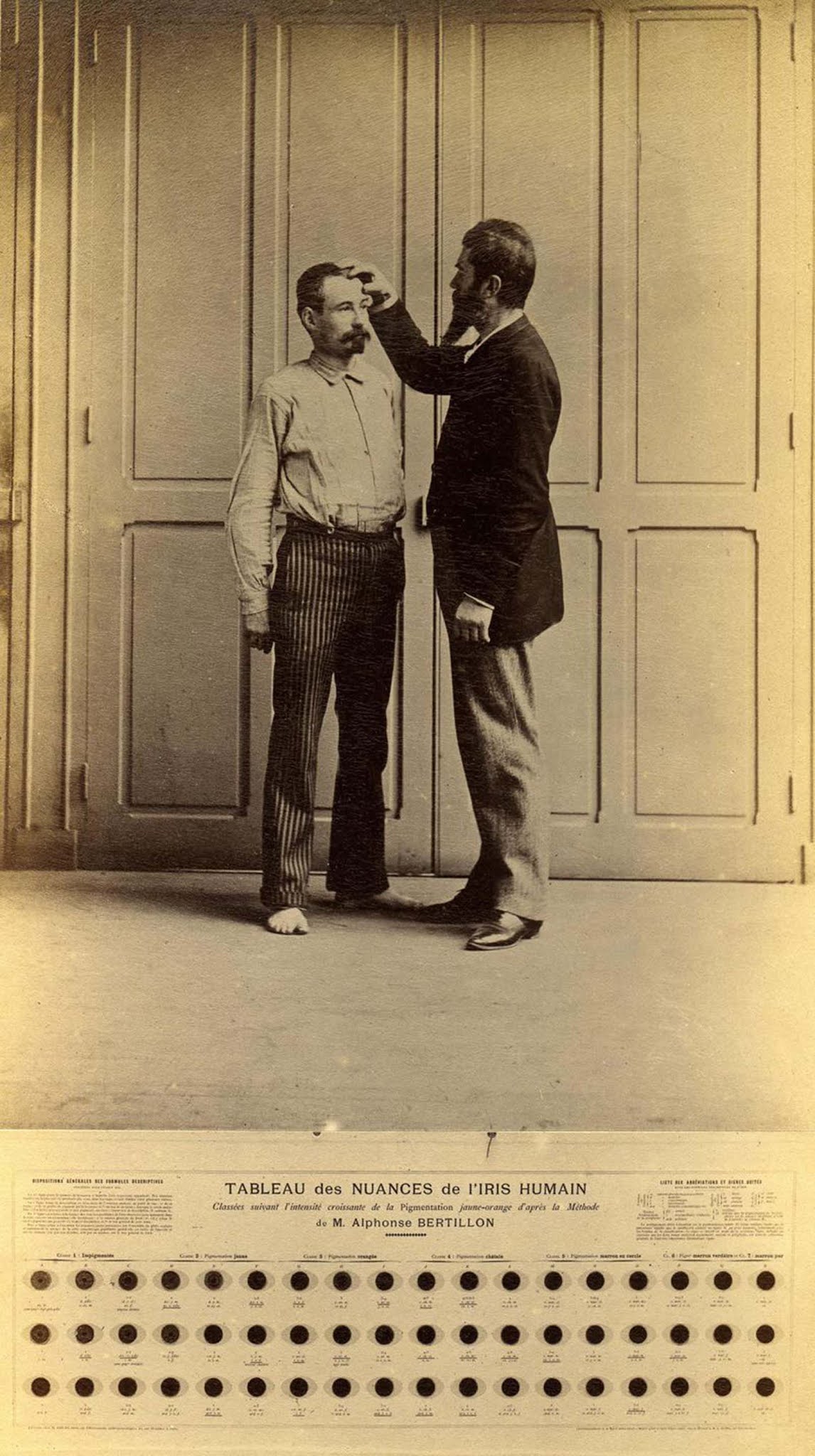

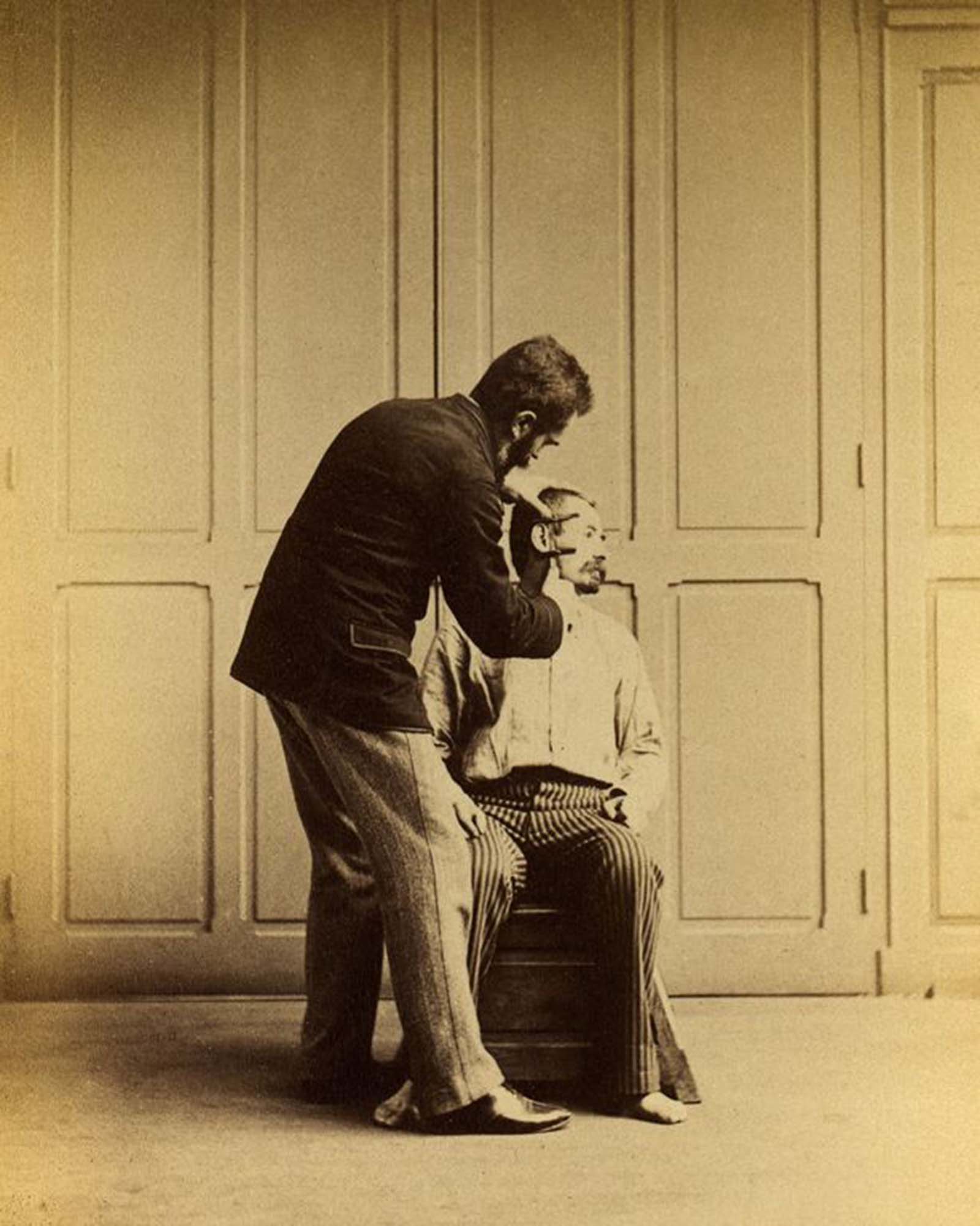

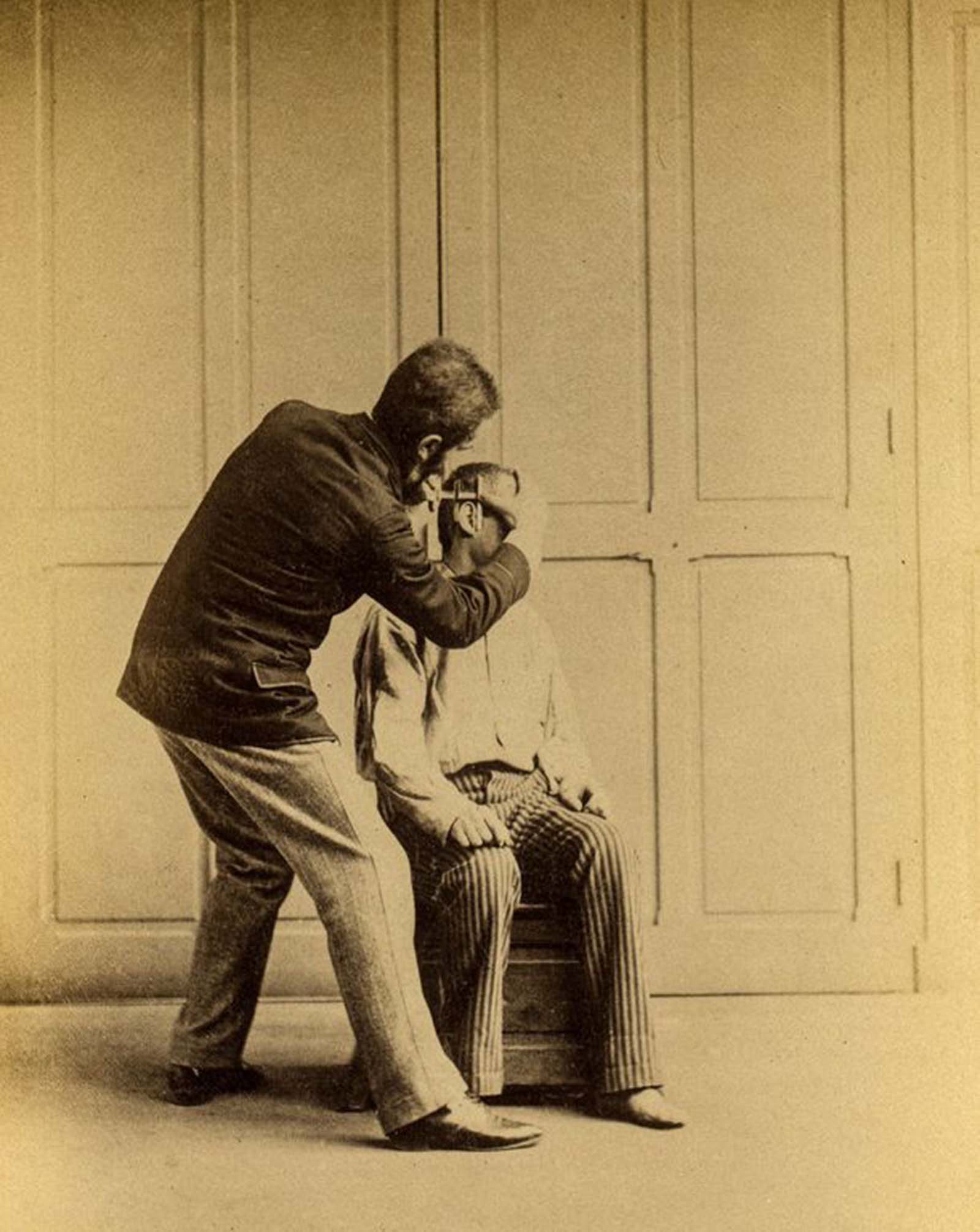

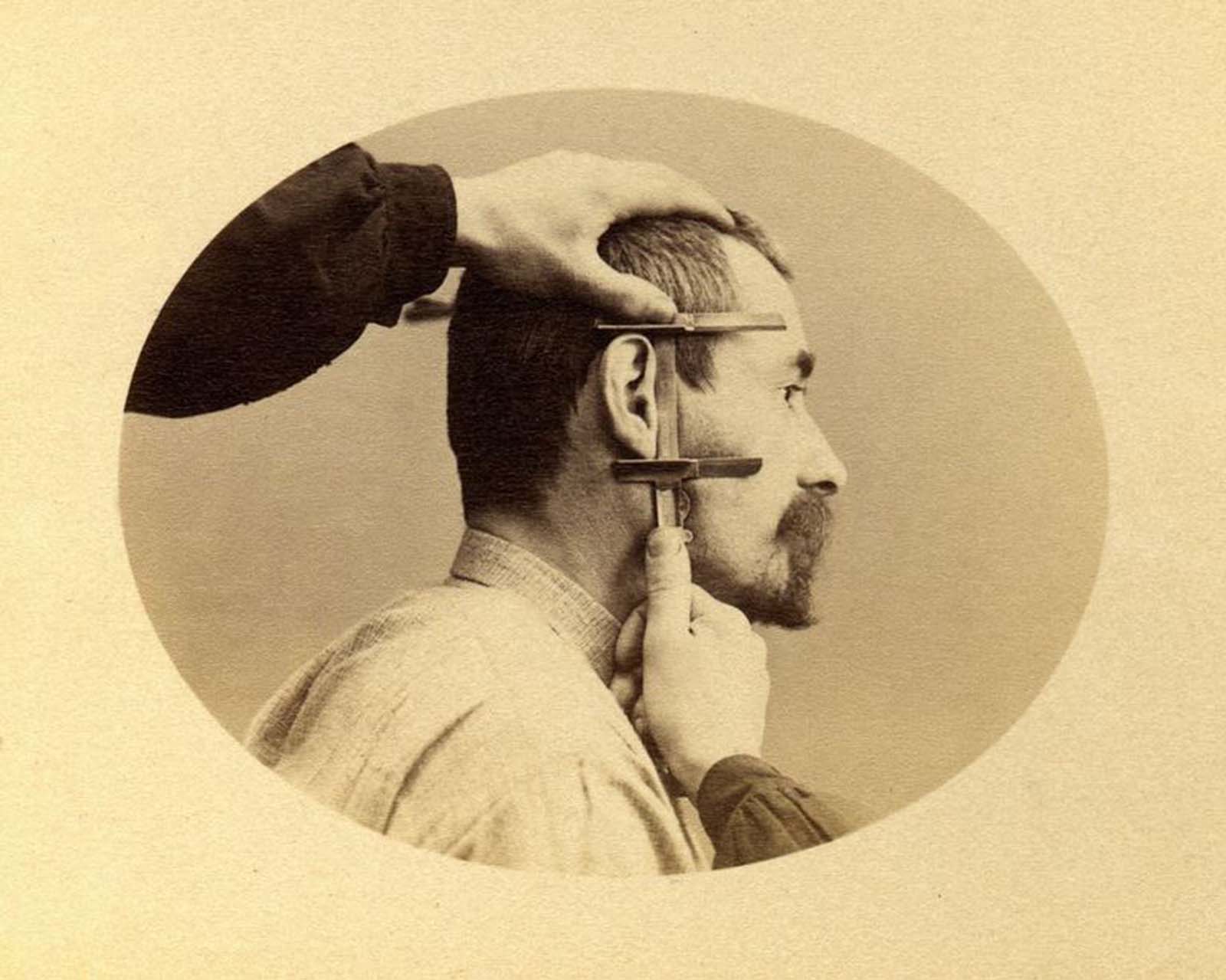

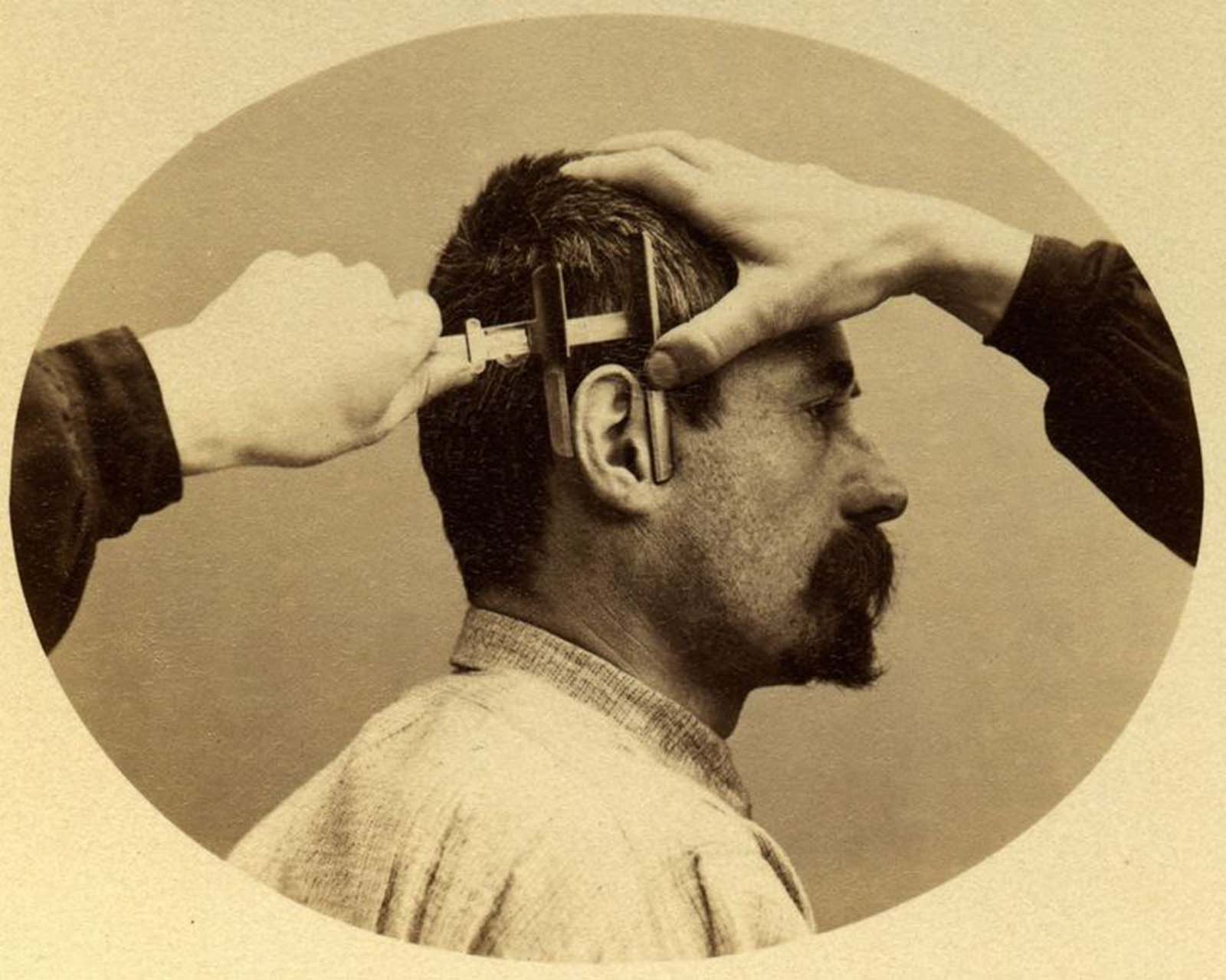

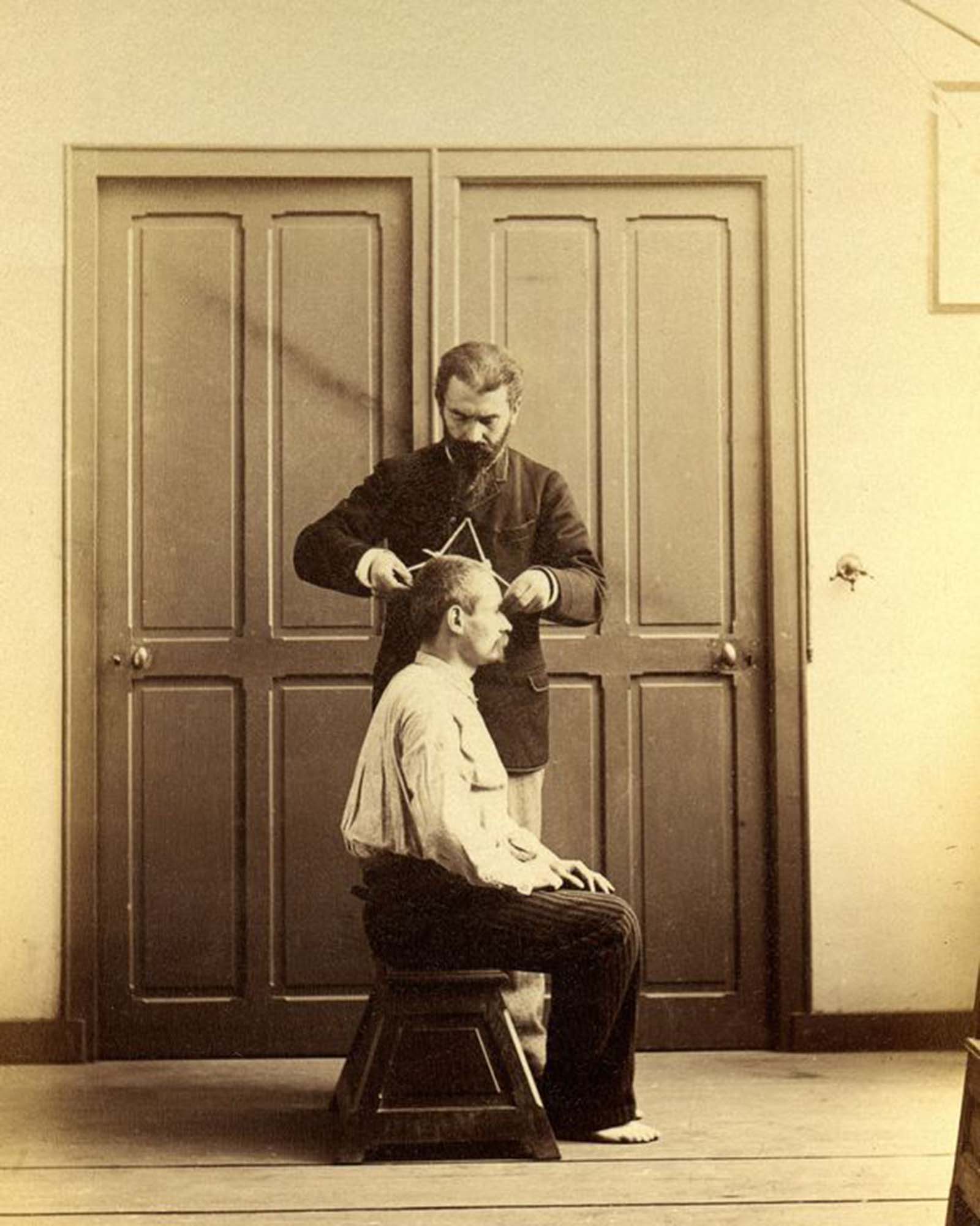

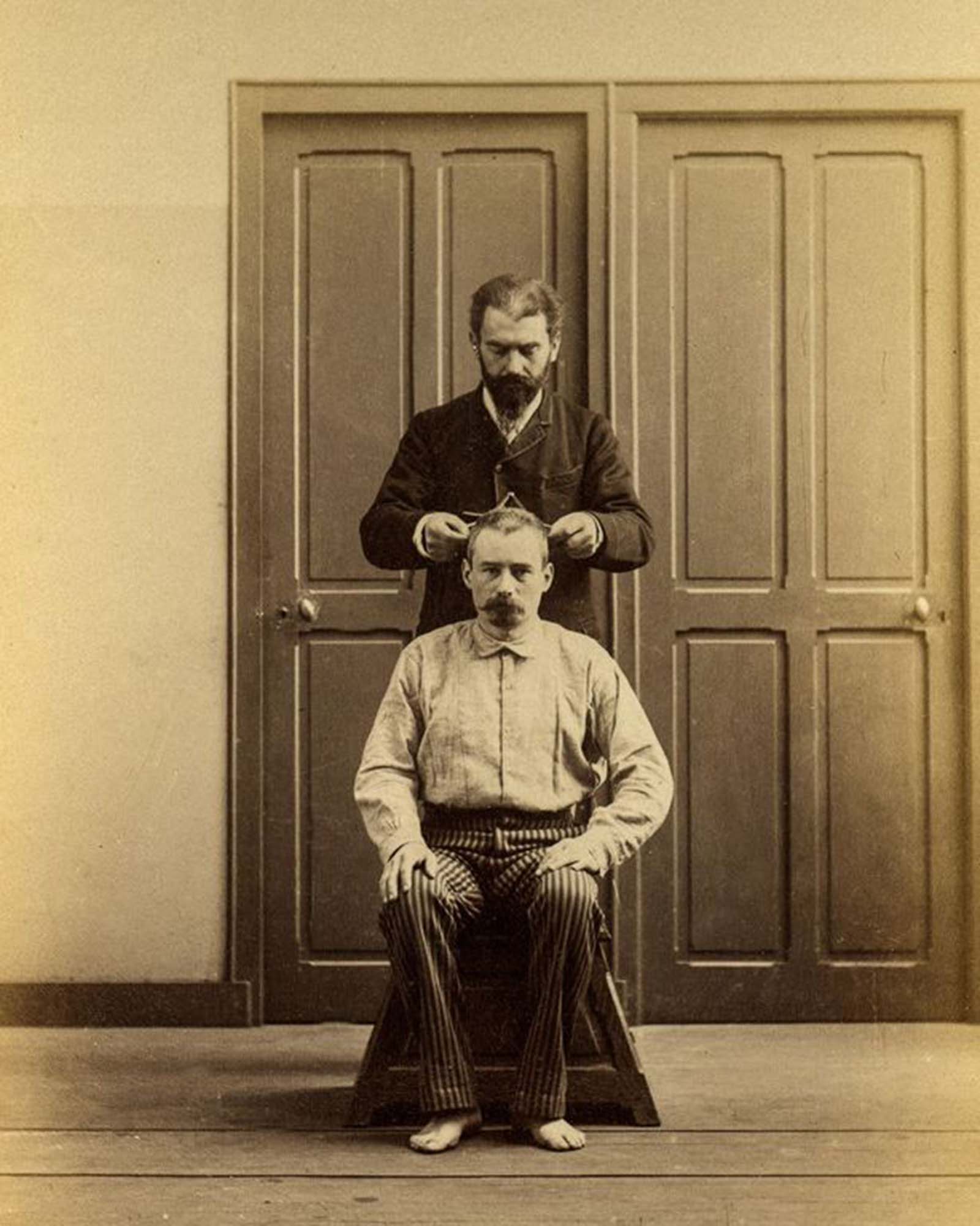

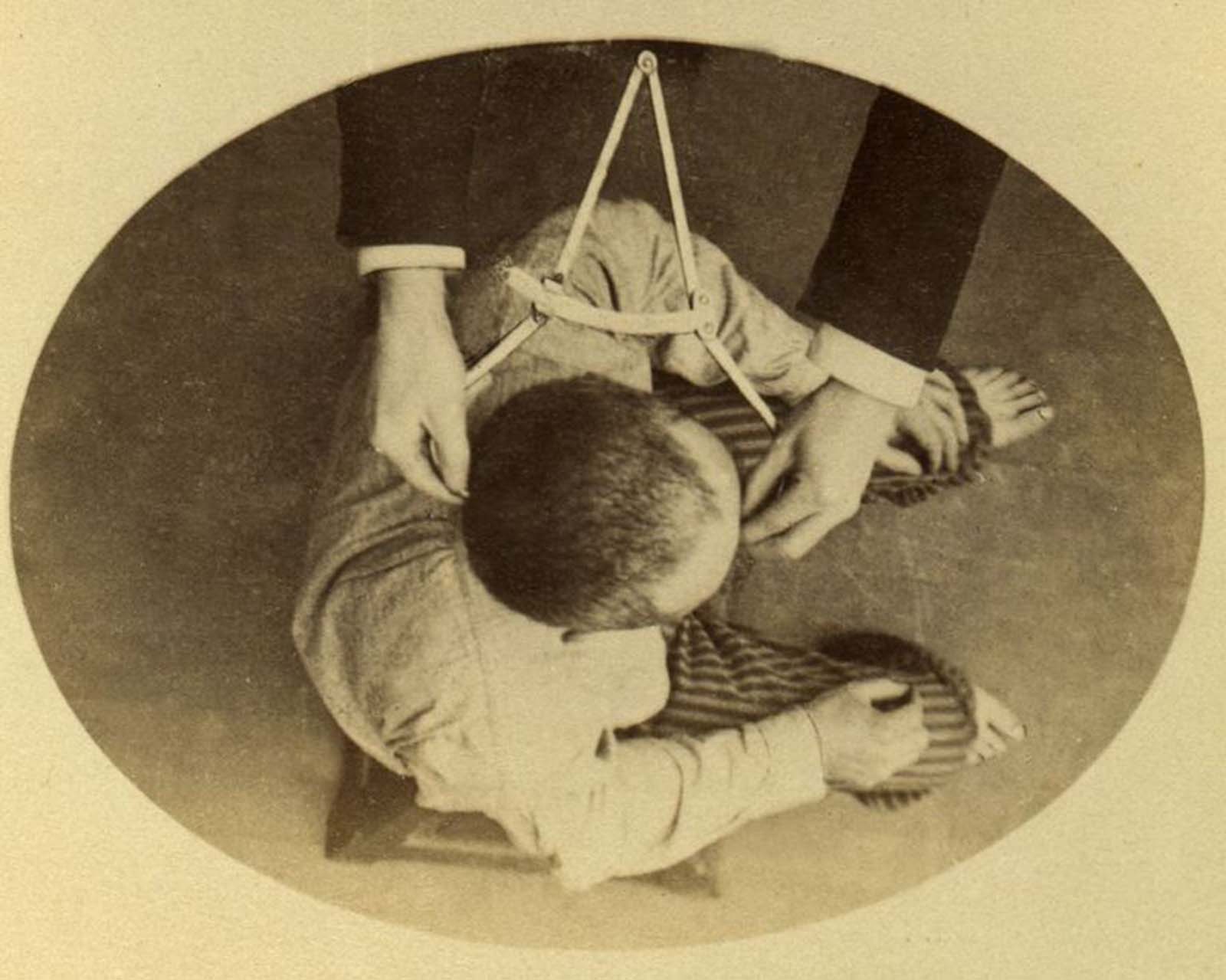

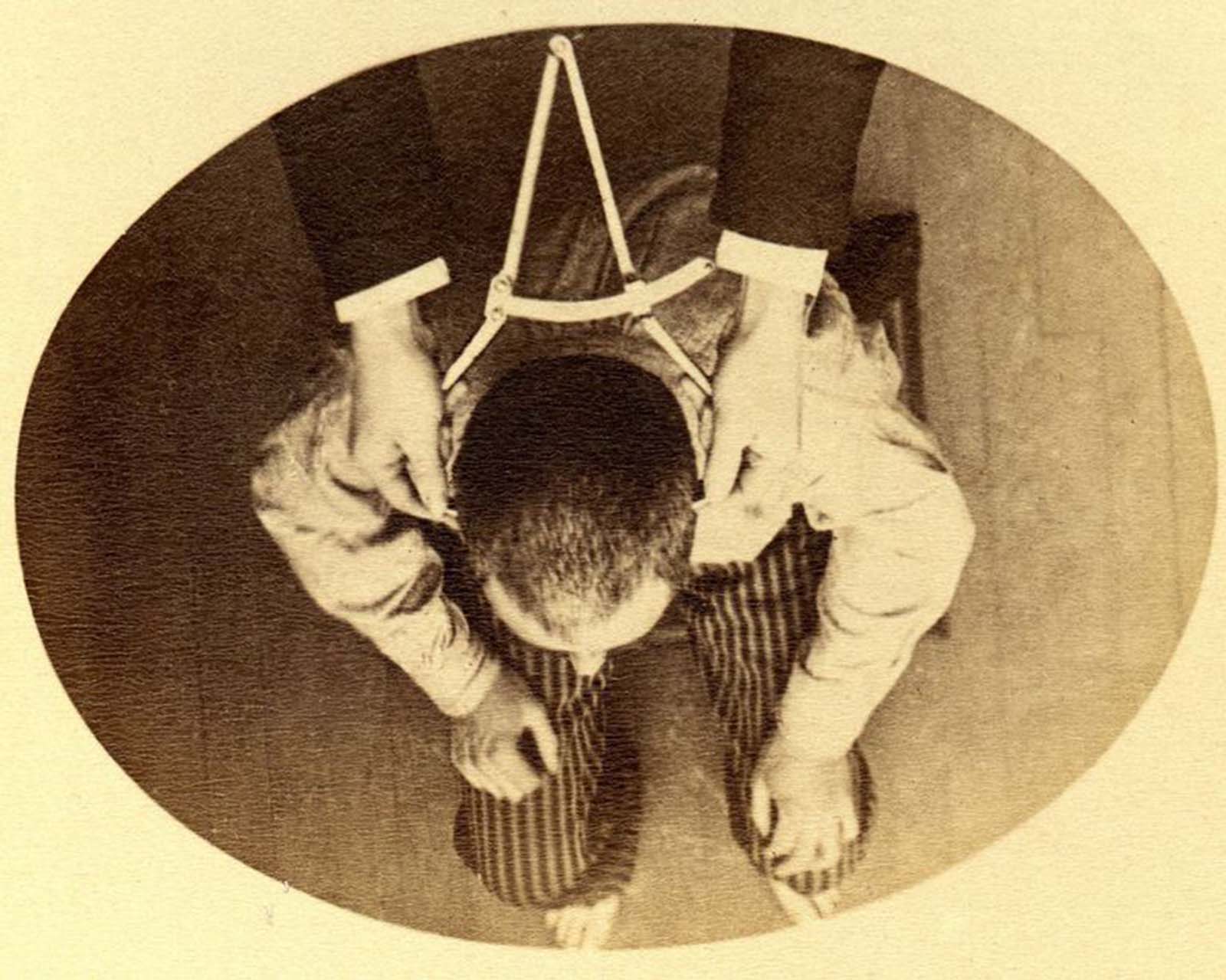

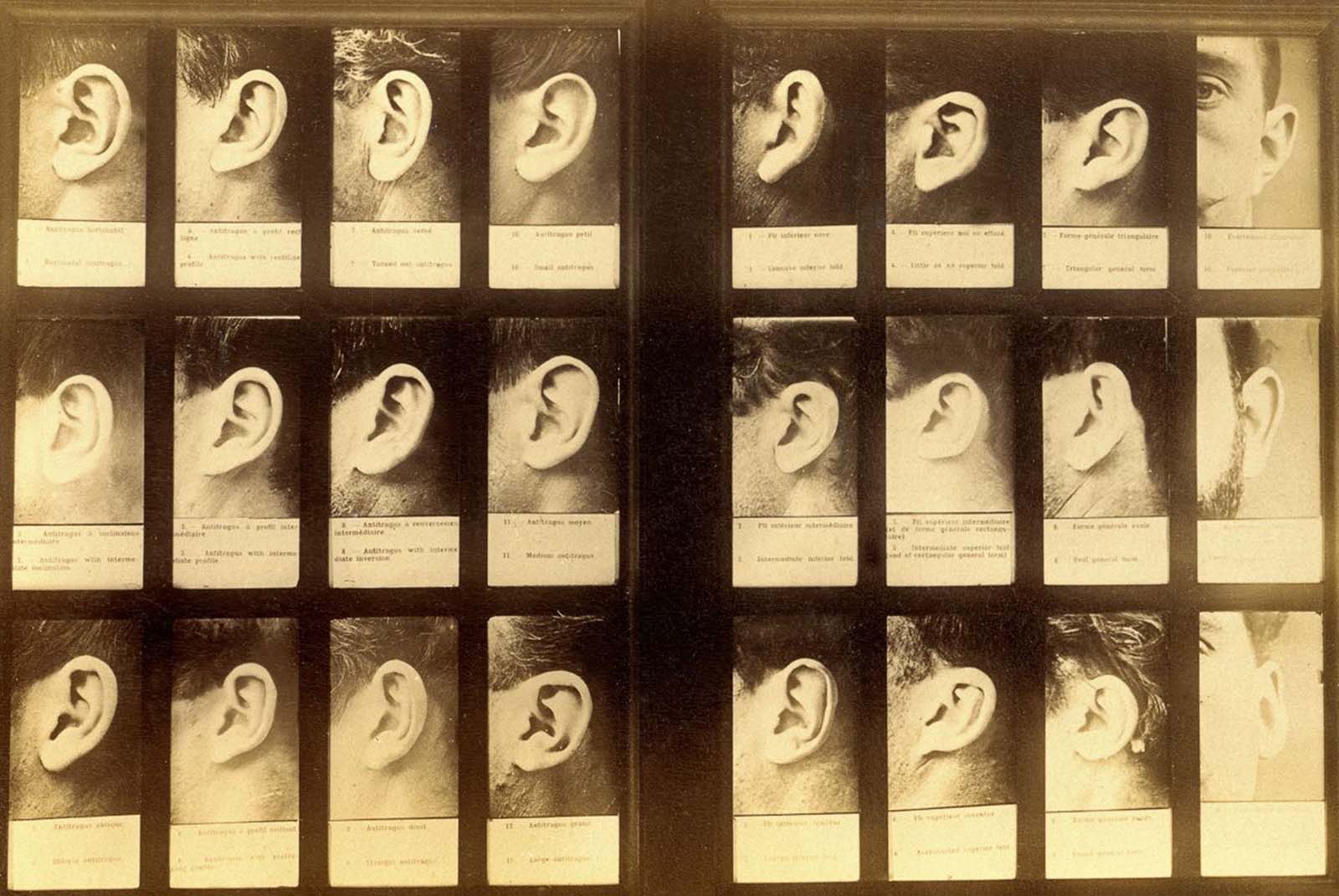

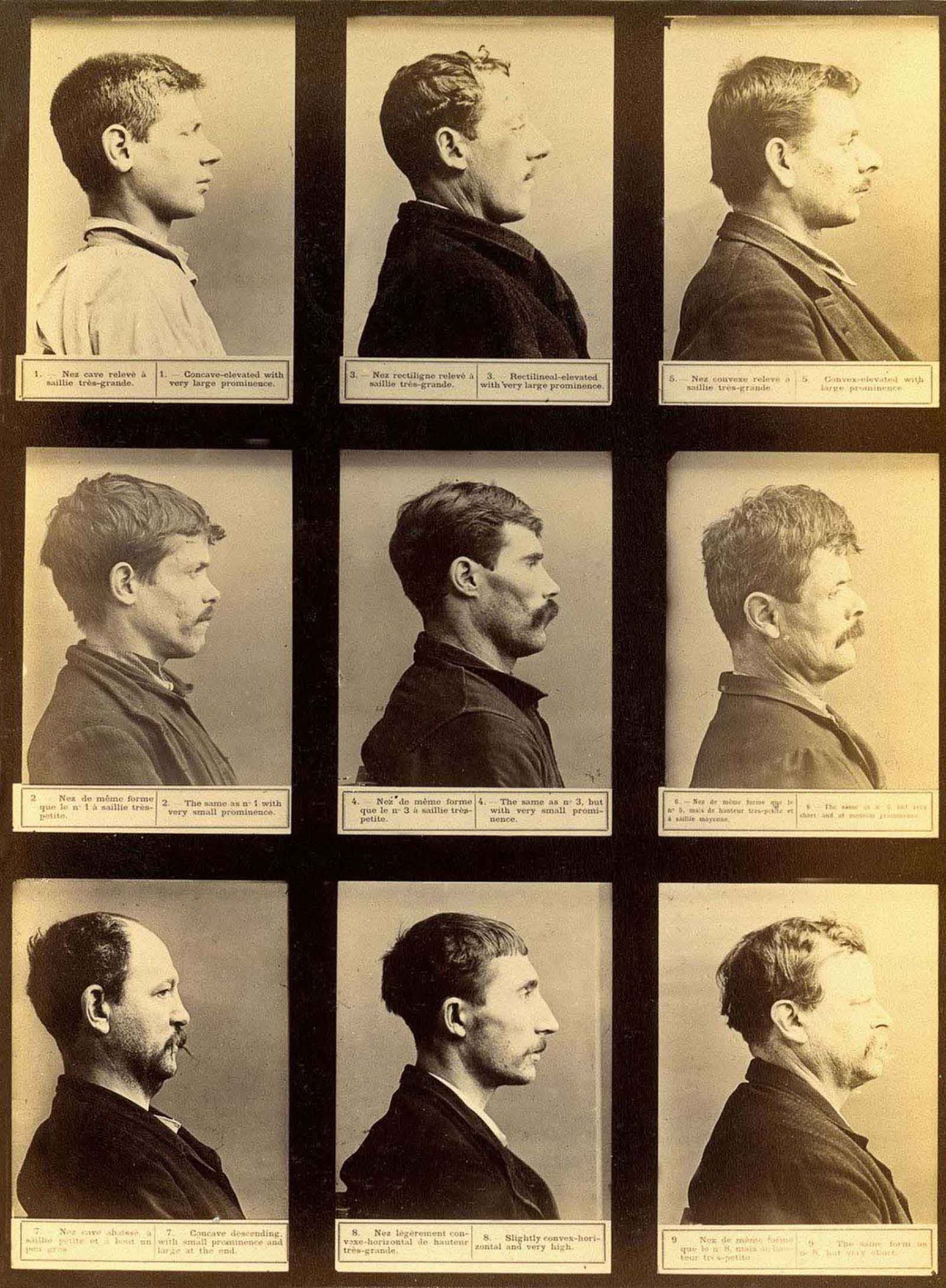

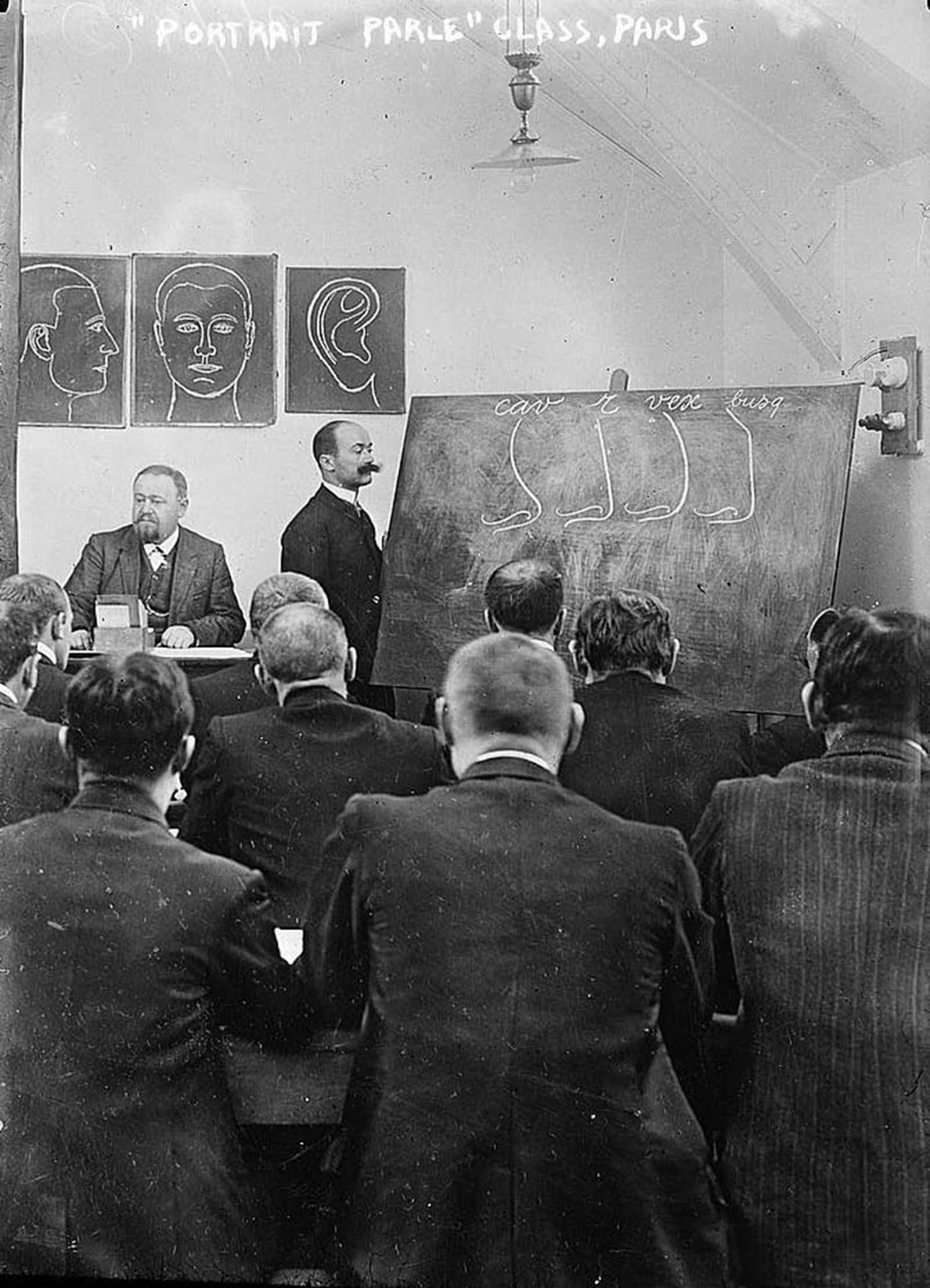

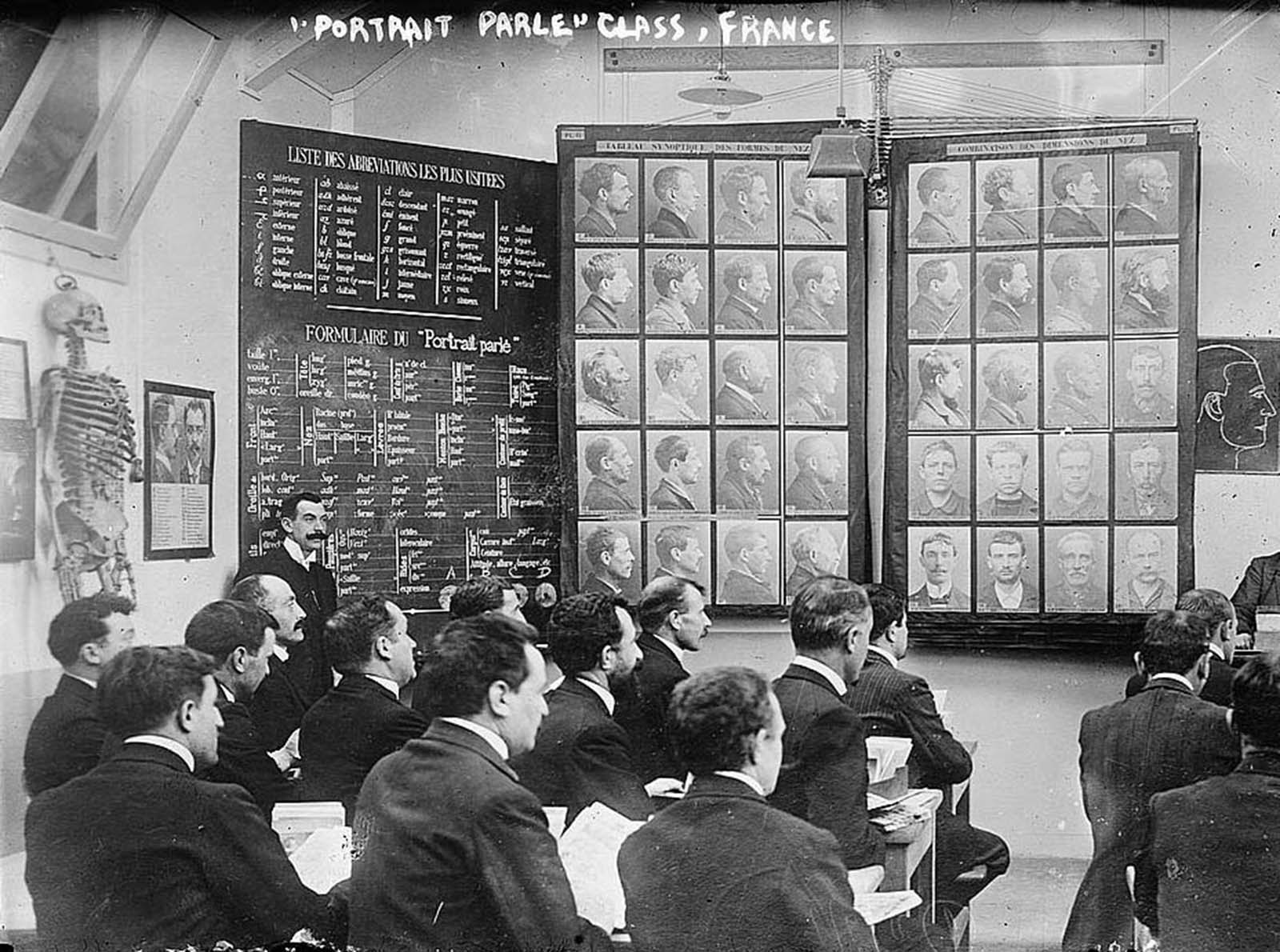

Son of Louis Adolphe Bertillon, a well-known anthropometrician who used statistics to describe humans, Alphonse Bertillon developed a verbal and visual system to describe criminals. His main interest was to identify recidivists – that is, repeat offenders. Called “speaking likeness,” Bertillon’s invention was what is known today as the mugshot. In 1888 Bertillon became Director of the Identification Bureau due to his invention of anthropometry – the first scientific system of criminal identification. The system, named bertillonage in his honor, consisted of recording eleven measurements of set parts of the head and body on a card which, accompanied by two photographs and additional physical details such as eye and hair color, established a unique, classable, and, most importantly, retrievable criminal record. Alphonse Bertillon considered this photographic information would produce a unique record of an individual that could be used by the police to identify criminals. The Bertillon system technique included standing height, sitting height (length of trunk and head), the distance between fingertips with arms outstretched, and size of the head, right ear, left foot, digits, and forearm. In addition, distinctive personal features, such as eye color, scars, and deformities, were noted. Bertillon stipulated the standardization of lighting conditions, exposure time, distance from the subject, pose, and scale of reduction, ensuring that a clear full face and profile portrait – a mugshot – appeared on each identification card. He also created the portrait parle, an identification chart of sectional photographs of facial features, such as ears and noses, mounted side by side to enable comparison and contrast. Although the system was based on scientific measures, it was known to have its flaws. For example, it may not have been able to accurately apply to children or women, as it was mostly designed for men who had reached full physical maturity and had short hair. Bertillon also created many other forensics techniques, including the use of galvanoplastic compounds to preserve footprints, ballistics, and the dynamometer, used to determine the degree of force used in breaking and entering. Replacing the unreliable system of eyewitness accounts, the bertillonage led to a marked increase in the number of arrests of multiple offenders and was subsequently adopted by police departments outside of France, such as New York City (1888), Argentina (1891), and Chicago (1894). Since bertillonage used photographs in the process of identification, in 1888 Bertillon annexed the prefecture’s photography studio to his own department and introduced a strictly uniform photographic technique to complement the system’s precision. Photography also played an important role in the solving of crimes, by identifying and documenting clues as well as people. Although not widely accepted as evidence in a court of law until the end of the nineteenth, forensic photography was used from the late 1850s to discredit forged documents, record crime scenes, including traffic accidents and provide evidence of injuries. Breaking down physical appearances into small, standardized units allowed unskilled clerks to file and retrieve criminal photographs. The creation of large information archives, such as those used in police work, strengthened government control of the populace and, with anthropological photographs, came close to fulfilling the abiding nineteenth-century dream of a vast, encyclopedic collection of images. Soon after the turn of the century bertillonage was supplanted by the more reliable system of dactyloscopy or identification by fingerprints. Ironically, this change of method caused a growth in the number of specialized police photographers as it increased the need for records to be made of impressions of fingers and handprints found at the crime scene.

(Photo credit: Wiki Commons / Adoc Photos / Corbis via Getty Images / Photography: A Cultural History / Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-century Photography). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe