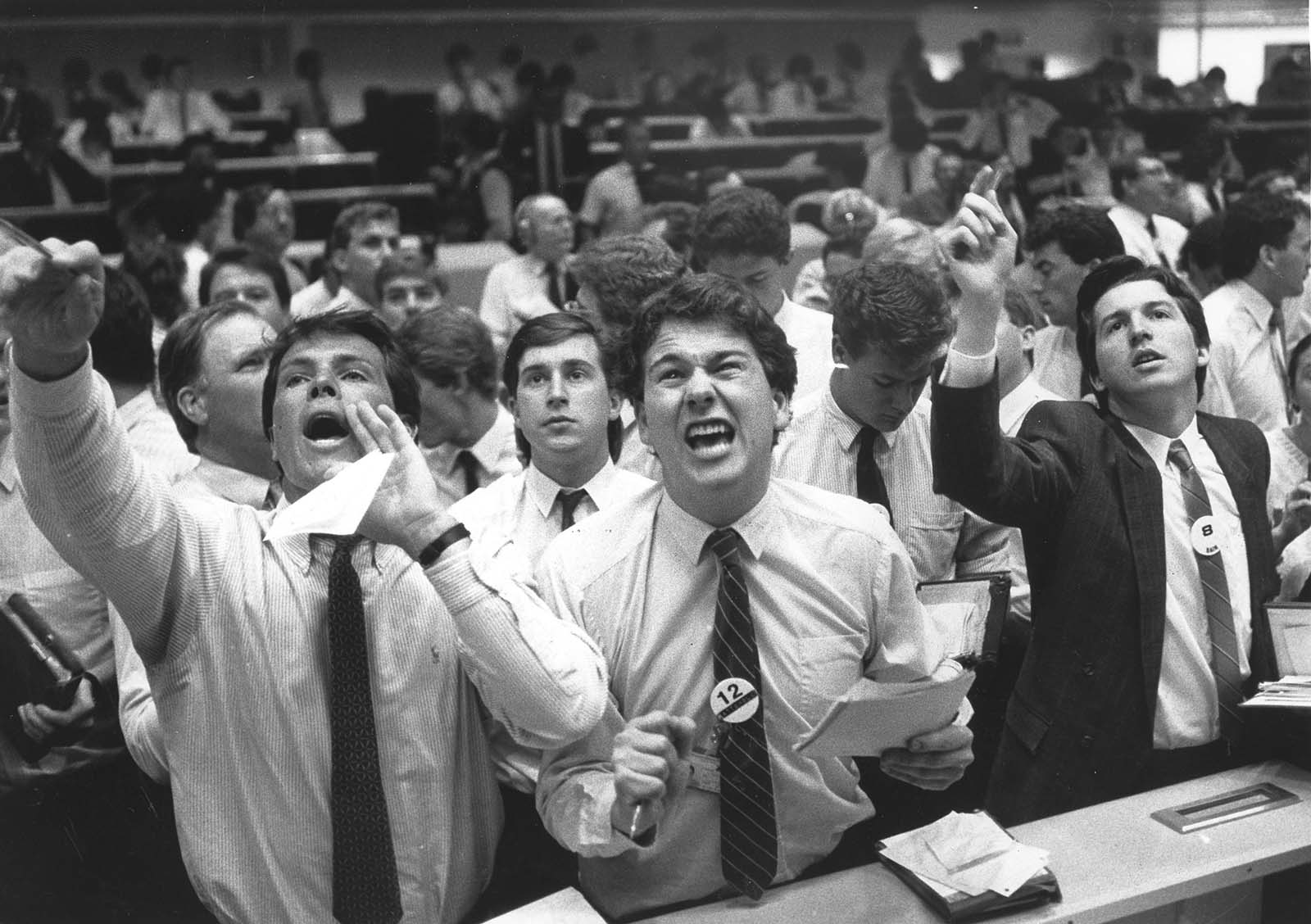

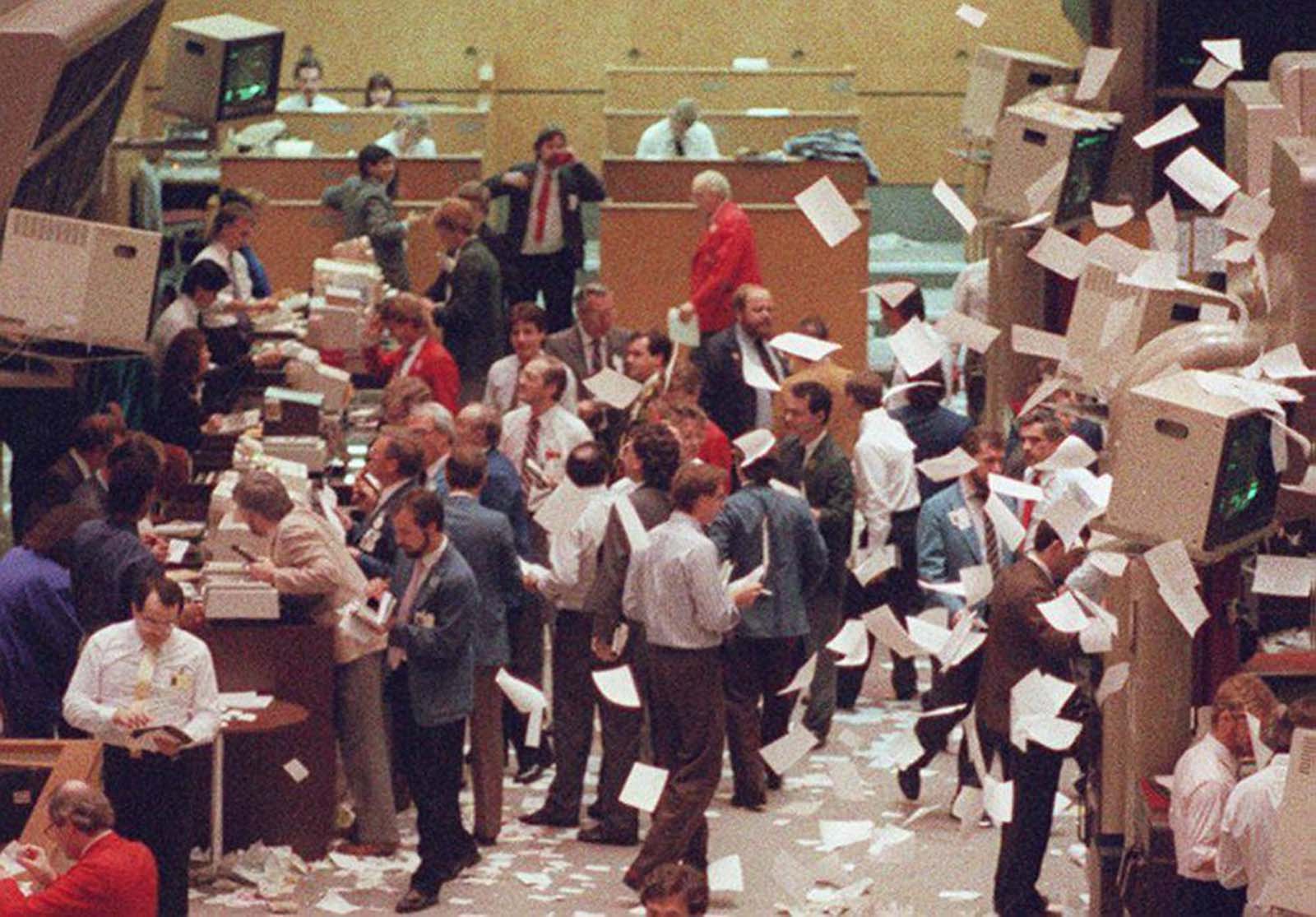

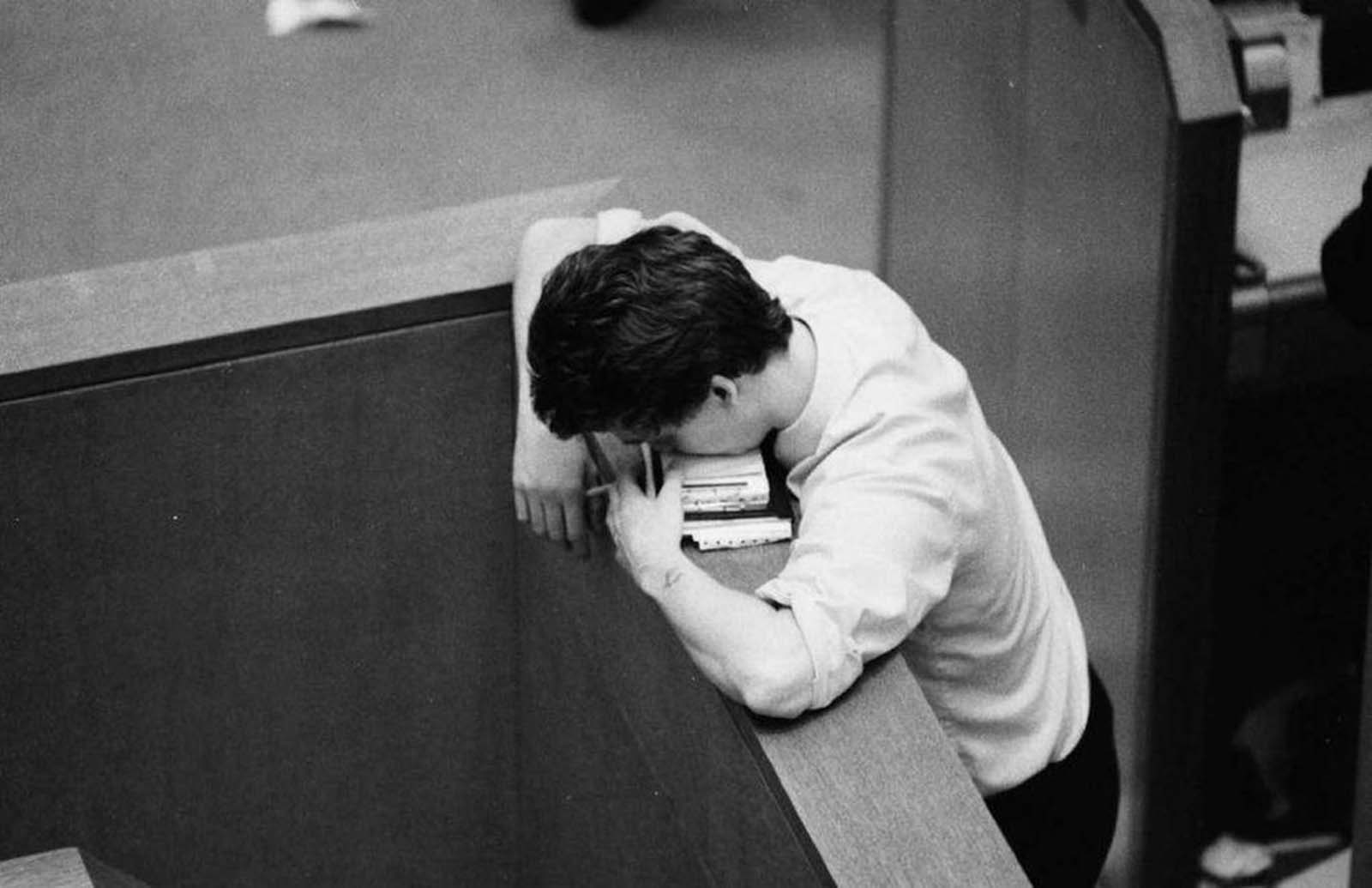

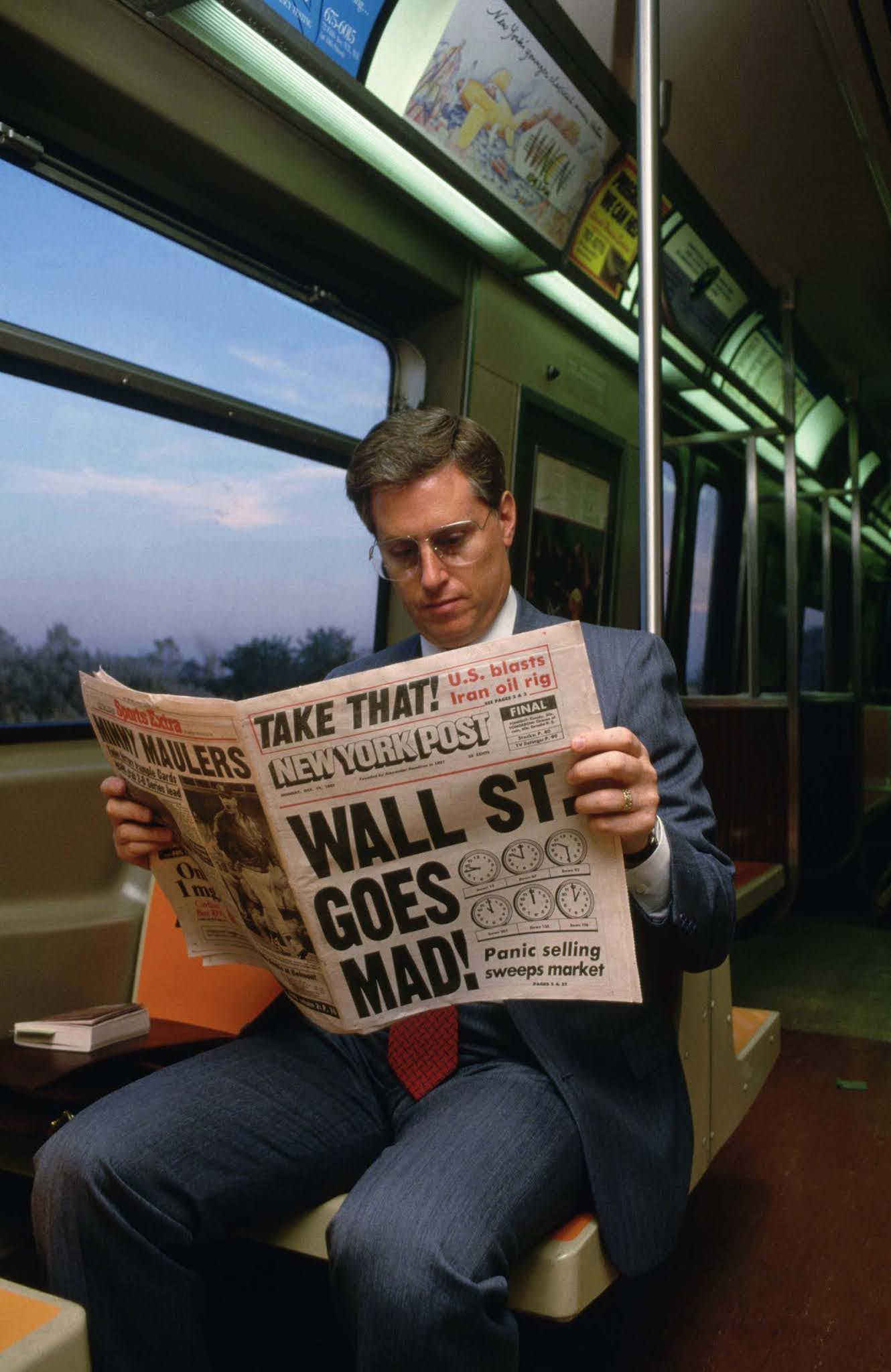

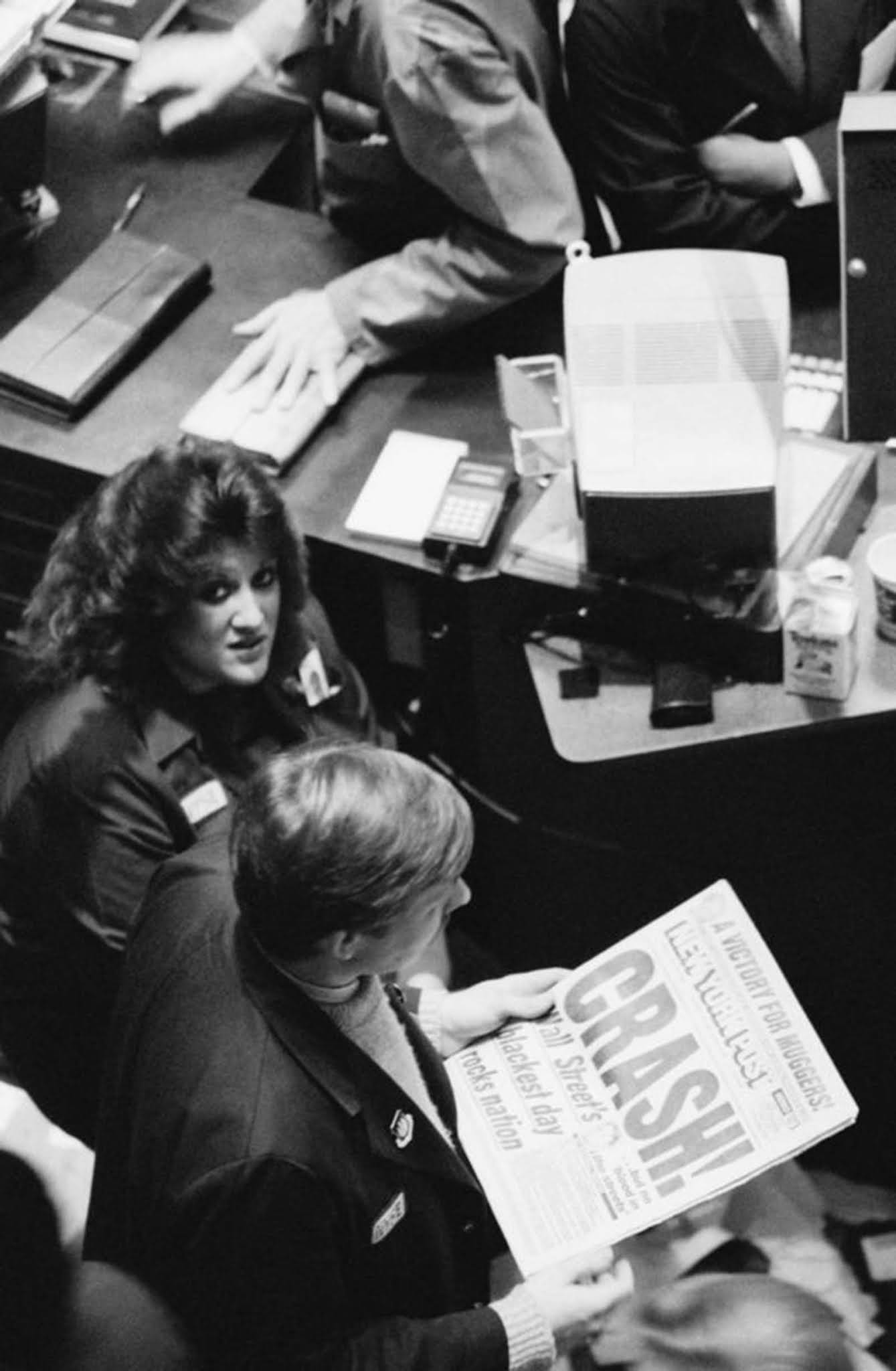

For example, on the worst day of the 1929 crash, the Dow Jones Industrial Average lost about 38 points, an insignificant move in modern markets. But on that day, the Dow had opened at just under 300 points, so that 38-point drop represented an unprecedented 12.8 percent decline. That record stood until the Black Monday crash of 1987. On that historic autumn Monday of 1987, it seemed possible that the entire American financial system would crack apart. The next day, it seemed certain that it would. The storm had not come out of a cloudless sky. There had been years of heedless expansion, months of growing anxiety, weeks of looming trouble, and fading options. Then, Monday dawned, a day so terrifying that those uneasy months and weeks seemed placid by comparison. Global markets teetered. High-speed computer trading, driven by mathematical models, outran the pace of mere humans. Poorly understood derivatives set off depth charges everywhere, revealing hidden links that bound together the banks, insurers, giant investors, and big brokerage firms that populated Wall Street. These connections stretched across all the regulatory borders that rival government agencies defended so fiercely. On that single day, the Dow Jones Industrial Average, the pulse rate of the most prominent stock market in the world, fell a heart-stopping 22.6 percent, still the largest one-day decline in Wall Street history. A one-day decline of 22.6 percent is still almost unthinkable. It was truly unthinkable for the men and women of 1987. We can look back on their experience, but when they looked back, they saw nothing that resembled Black Monday, not during the Great Depression, not when America went to war, not even after a presidential assassination. Until 1987, a very bad day in the stock market meant a decline of 4 or 5 percent. A horrible day meant a drop of 10 or 11 percent, a figure exceeded only during the historic crash of 1929. Then, on Black Monday, the unthinkable suddenly became unforgettable, a market crash so steep and so fast it seemed that the entire financial system would simply shake apart like an airplane plunging to earth. On that day, the new toys of Wall Street, derivatives and computer-assisted trading, fed a justifiable fear that an overdue market downturn would become an uncontrollable meltdown. The avalanche of selling briefly halted a key Chicago market and came within minutes of officially shutting down the New York Stock Exchange. Hong Kong closed its market for a week. Tokyo and London, financial centers almost on par with New York, were battered. The aftershock hit days, weeks, and even months later. It took two years for the market to climb back to its 1987 peak. Black Monday was the product of profound but poorly understood changes in the shape of the marketplace over the previous decade. Wall Street (shorthand for the nation’s entire financial industry) had become a place striving to get both bigger and broader, seeking profit in as many diverse markets as possible. Meanwhile, Wall Street’s clients had undergone a staggering mutation: they were exponentially larger and more demanding, and they became far more homogenized, subscribing confidently to academic theories that led giant herds of investors to pursue the same strategies at the same time with a vast amount of money. As a result of these two structural changes, government regulators in Washington faced a new world where, time and again, a financial crisis would suddenly become contagious. Thanks to giant diversified firms and giant diversifying investors, a failure in one regulator’s market could spread like a wind-borne plague and infect those overseen by other regulators. After years of these outbreaks, Black Monday was the contagious crisis that the system nearly didn’t survive. When measured in United States dollars, eight markets declined by 20 to 29%, three by 30 to 39% (Malaysia, Mexico, and New Zealand), and three by more than 40% (Hong Kong, Australia, and Singapore). The least affected was Austria (a fall of 11.4%) while the most affected was Hong Kong with a drop of 45.8%. Out of twenty-three major industrial countries, nineteen had a decline greater than 20%. Worldwide losses were estimated at US$1.71 trillion. Although program trading contributed greatly to the severity of the crash, the exact catalyst is still unknown and possibly forever unknowable. With complex interactions between international currencies and markets, hiccups are likely to arise. Since 1987, a number of protective mechanisms have been built into the market to prevent panic selling, such as trading curbs and circuit breakers. In the photos collected here, exchange floor traders look exasperated, brokers gaze worriedly at television screens, seemingly unsure of whether they need to go to work anymore. Overall, a sense of powerlessness permeates each image, a sense of fear for the future of the economy. (Photo credit AP / Corbis / Getty Images / The Canadian Press / Article based on A First-Class Catastrophe: The Road to Black Monday, the Worst Day in Wall Street History by Diana B. Henriques). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe