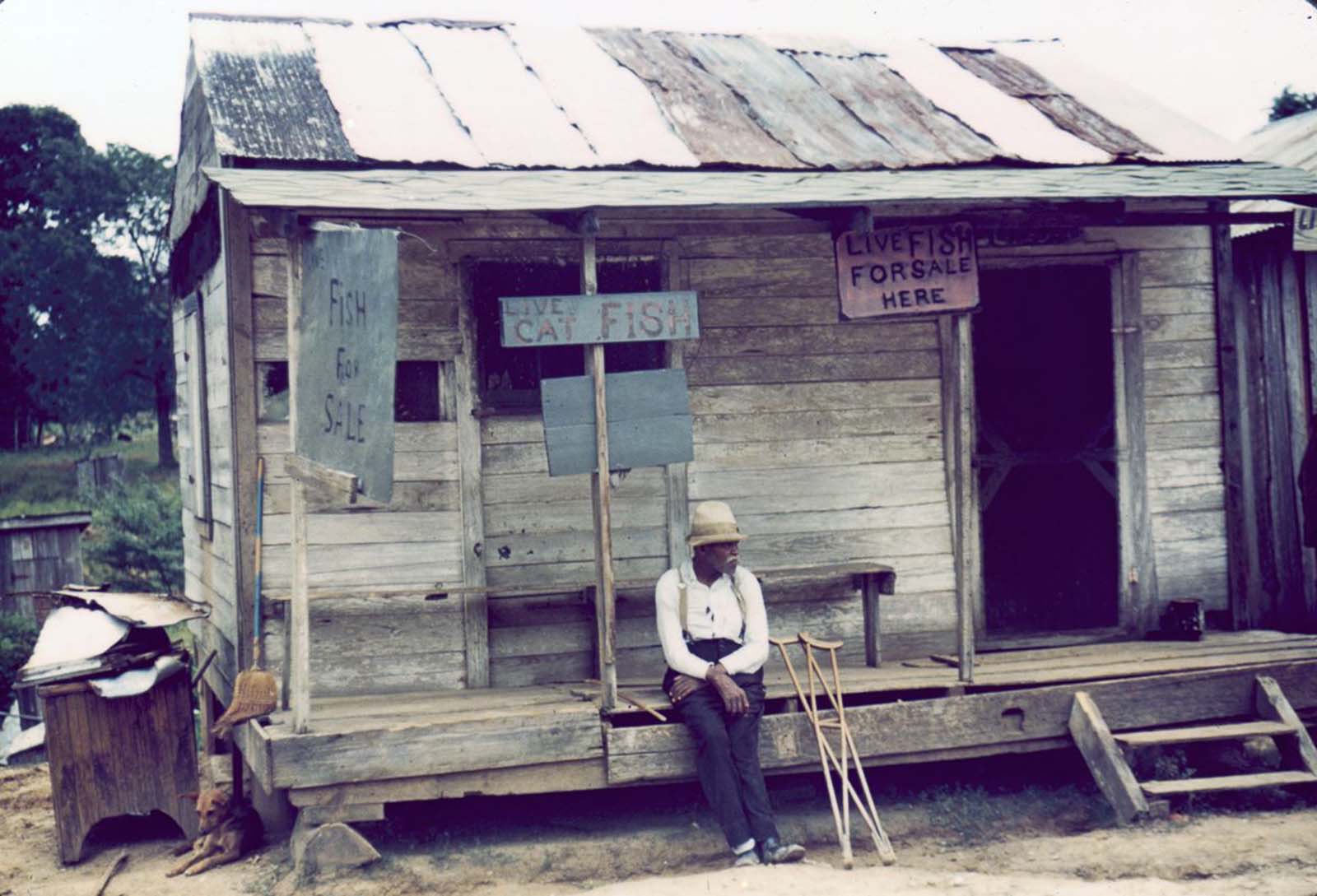

Croppers were assigned a plot of land to work, and in exchange owed the owner a share of the crop at the end of the season, usually one half. The owner provided the tools and farm animals . Farmers who owned their own mule and plow were at a higher stage, and were called tenant farmers: They paid the landowner less, usually only a third of each crop. In both cases, the farmer kept the produce of gardens. The sharecropper purchased seed, tools, and fertilizer, as well as food and clothing, on credit from a local merchant, or sometimes from a plantation store. At harvest time, the cropper would harvest the whole crop and sell it to the merchant who had extended credit. Purchases and the landowner’s share were deducted and the cropper kept the difference—or added to his debt. With fickle harvests and lopsided contracts, many sharecroppers ended up deeply indebted to the merchant or landlord and tied to the land, leading to the system being called “slavery by another name.” In the Reconstruction-era United States, sharecropping was one of few options for penniless freedmen to support themselves and their families. Other solutions included the crop-lien system (where the farmer was extended credit for seed and other supplies by the merchant), a rent labor system (where the former slave rents his land but keeps his entire crop), and the wage system (worker earns a fixed wage, but keeps none of their crops). Sharecropping was by far the most economically efficient, as it provided incentives for workers to produce a bigger harvest. It was a stage beyond simply hired labor because the sharecropper had an annual contract. During Reconstruction, the federal Freedmen’s Bureau ordered the arrangements and wrote and enforced the contracts. By the early 1930s, there were 5.5 million white tenants, sharecroppers, and mixed cropping/laborers in the United States; and 3 million blacks. In Tennessee, whites made up two-thirds or more of the sharecroppers. In Mississippi, by 1900, 36% of all white farmers were tenants or sharecroppers, while 85% of black farmers were. In Georgia, fewer than 16,000 farms were operated by black owners in 1910, while, at the same time, African Americans managed 106,738 farms as tenants. The situation of landless farmers who challenged the system in the rural South as late as 1941 has been described thus: “he is at once a target subject of ridicule and vitriolic denunciation; he may even be waylaid by hooded or unhooded leaders of the community, some of whom may be public officials. If a white man persists in ‘causing trouble’, the night riders may pay him a visit, or the officials may haul him into court; if he is a Black, a mob may hunt him down.”. In the 1930s and 1940s, increasing mechanization virtually brought the institution of sharecropping to an end in the United States. The sharecropping system in the U.S. increased during the Great Depression with the creation of tenant farmers following the failure of many small farms throughout the Dustbowl. Traditional sharecropping declined after the mechanization of farm work became economical in the mid-20th century. As a result, many sharecroppers were forced off the farms and migrated to cities to work in factories or become migrant workers in the Western United States during World War II. (Photo credit: Jack Delano / Library of Congress). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe