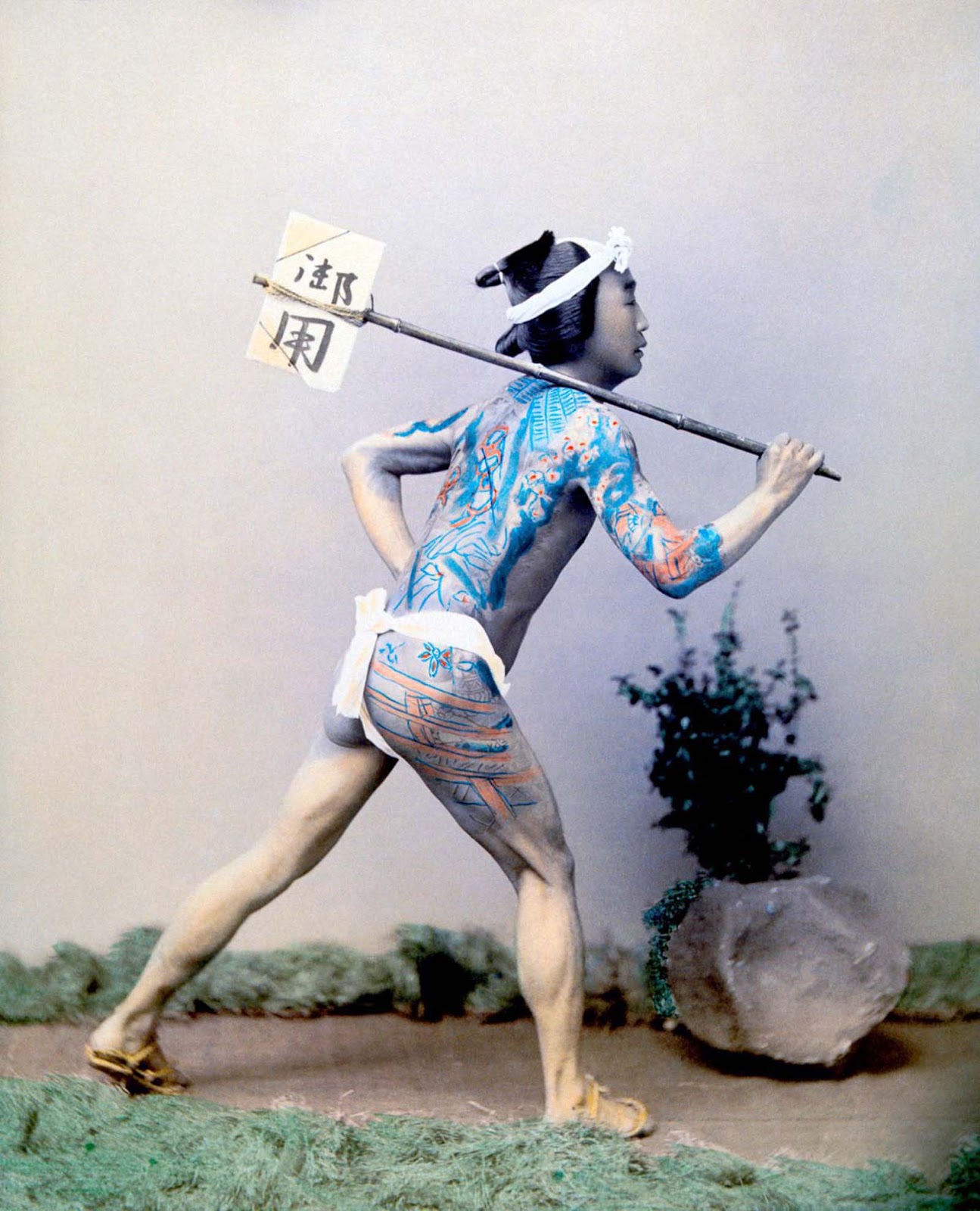

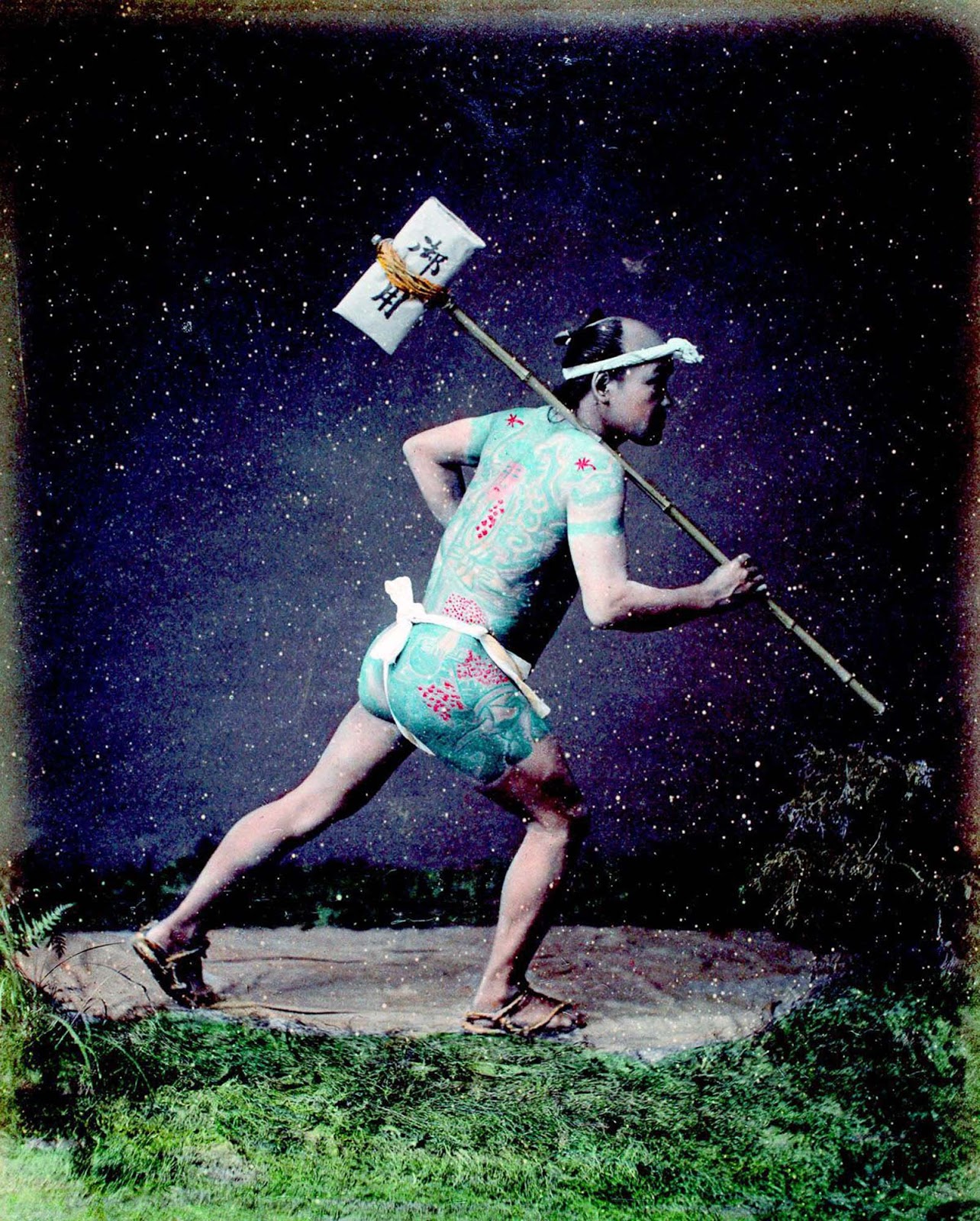

The first written record of tattoos in Japan was from 300 A.D., found in the text History of the Chinese Dynasties. In this text, Japanese men would tattoo their faces and decorate their bodies with tattoos which became a normal part of their society; however, a shift began in the Kofun period between 300 and 600 A.D where tattoos took on a more negative light. In this period criminals began to be marked with tattoos, similar to the Roman Empire where slaves were marked with descriptive phrases of the crime they had committed. This stigma towards body modification only worsened: by the 8th century Japanese rulers had adopted many of the Chinese attitudes and cultures. As tattoos fell into decline, the first record of them being used explicitly as a punishment was 720 A.D., where criminals were tattooed on the forehead so people could see that they had committed a crime. These markings were reserved for only the most serious crimes. People bearing tattoos were ostracized from their families and were rejected by society as a whole. The tattoos experienced somewhat of popularization in the Edo period through the Chinese novel Suikoden, which depicted heroic scenes with bodies decorated with tattoos. This novel became so popular, people began to get these tattoos as physical rendering in the form of paintings. This practice eventually evolved into what we know today as irezumi or Japanese tattooing. This practice would have a monumental impact, with many woodblock artists converting their woodblock printing tools to begin creating art on the skin. Tattoos became a status symbol during this time; it is said that wealthy merchants were prohibited from wearing and displaying their wealth through jewelry, so instead, they decorated their entire bodies with tattoos to show their riches. By the end of the 17th century, penal tattooing had largely been replaced with other forms of punishment. The reason why tattooing was once again associated with gangs, however, was that criminals were able to cover up these penal tattoos with larger more elaborate decorative tattoos. The Yakuza members began using tattoos for whom receiving a painful and illegal tattoo was considered evidence of one’s courage and loyalty to the outlaw lifestyle. However, once again tattoos became outlawed in 1868. In the Meiji period, the emperor once again banned tattoos as he thought them distasteful and barbaric and to westernize the country. Nevertheless, fascinated foreigners went to Japan seeking the skills of tattoo artists, and traditional tattooing continued underground. Tattooing was legalized by the occupation forces in 1948 but has retained its image of criminality. For many years, traditional Japanese tattoos were associated with the Yakuza mafia, and many businesses in Japan (such as public baths, fitness centers, and hot springs) still ban customers with tattoos. Although tattoos have gained popularity among the youth of Japan due to Western influence, there is still a stigma on them among the general consensus. (Photo credit: Hulton Archive / Universal History Archive). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe