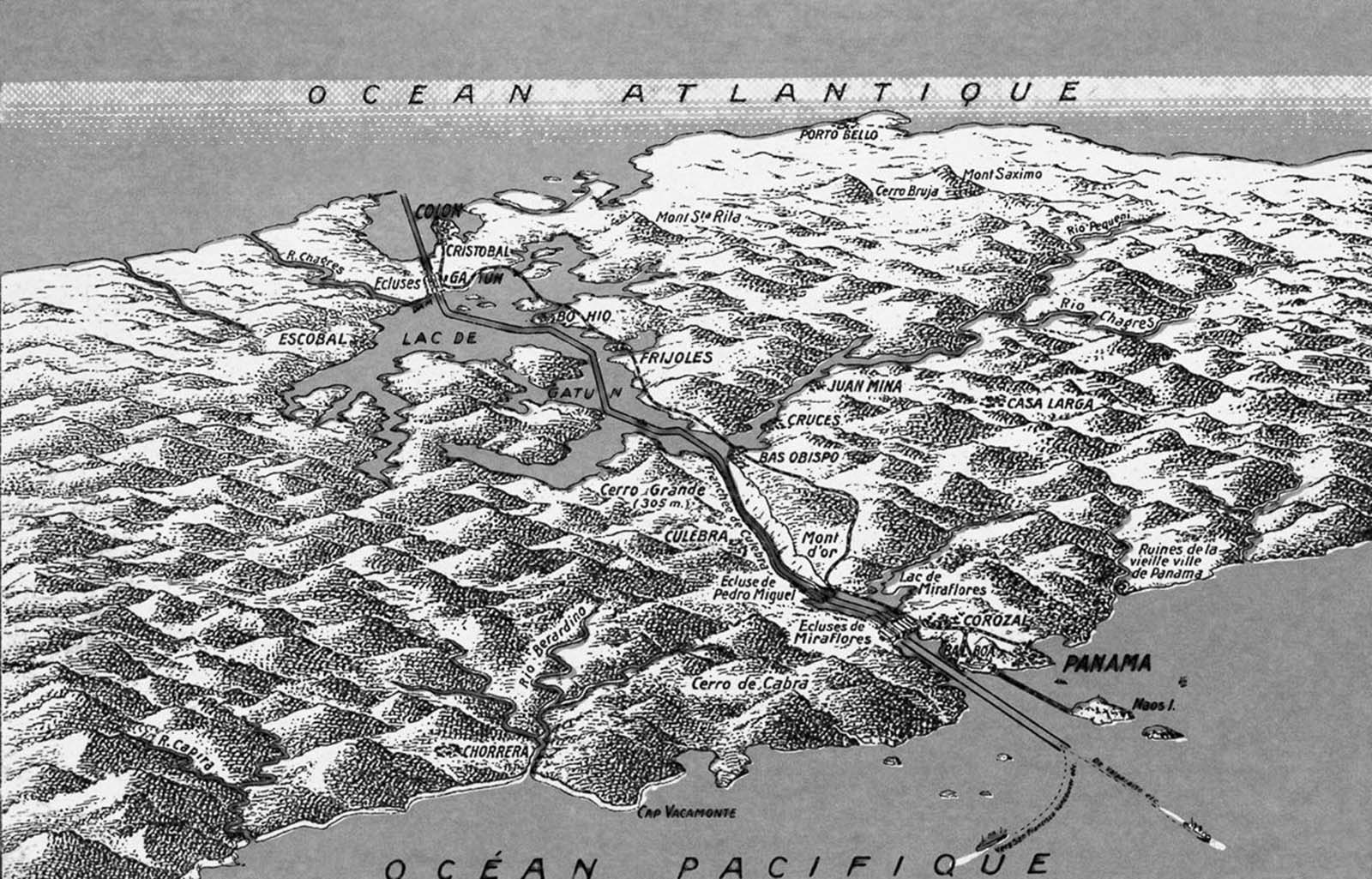

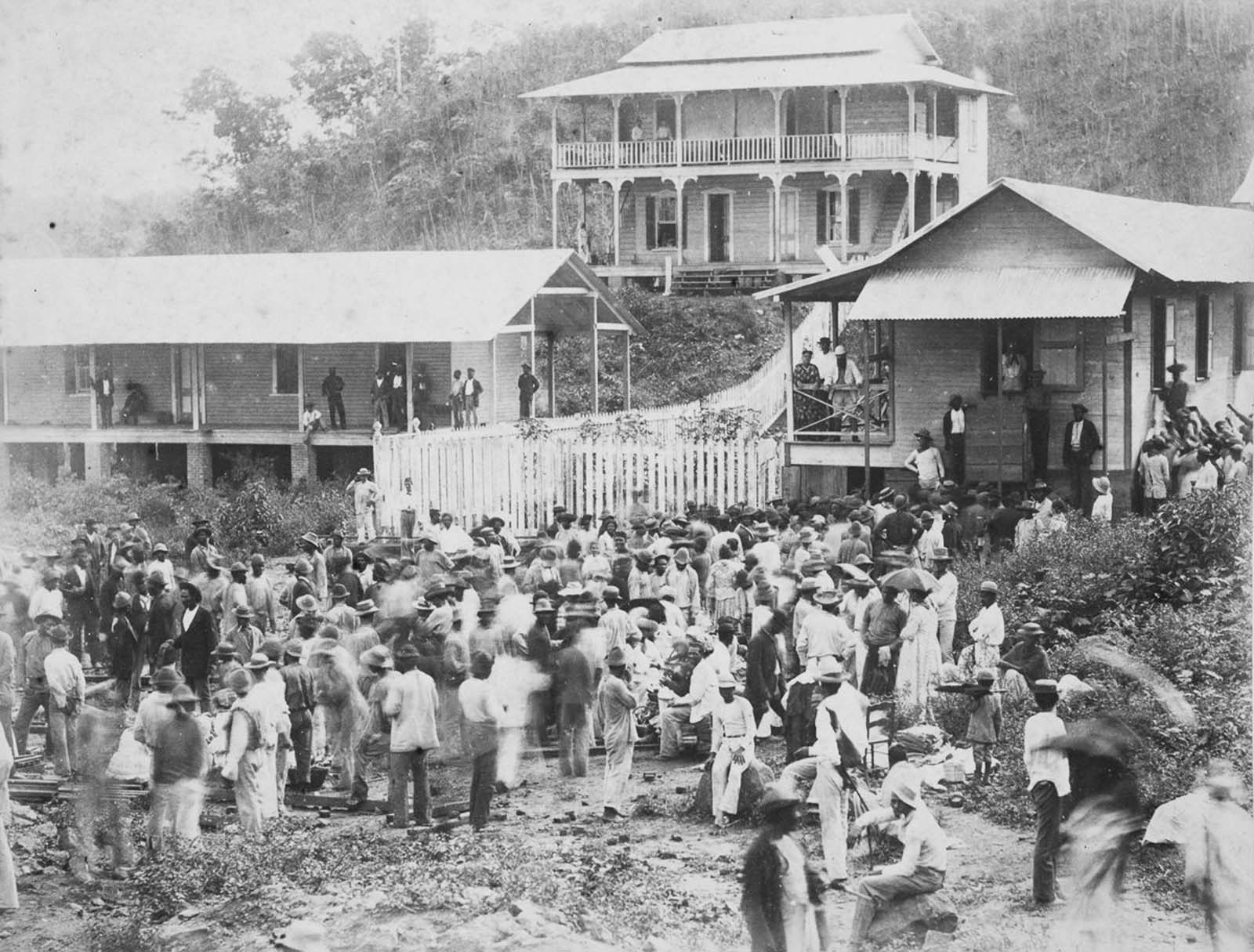

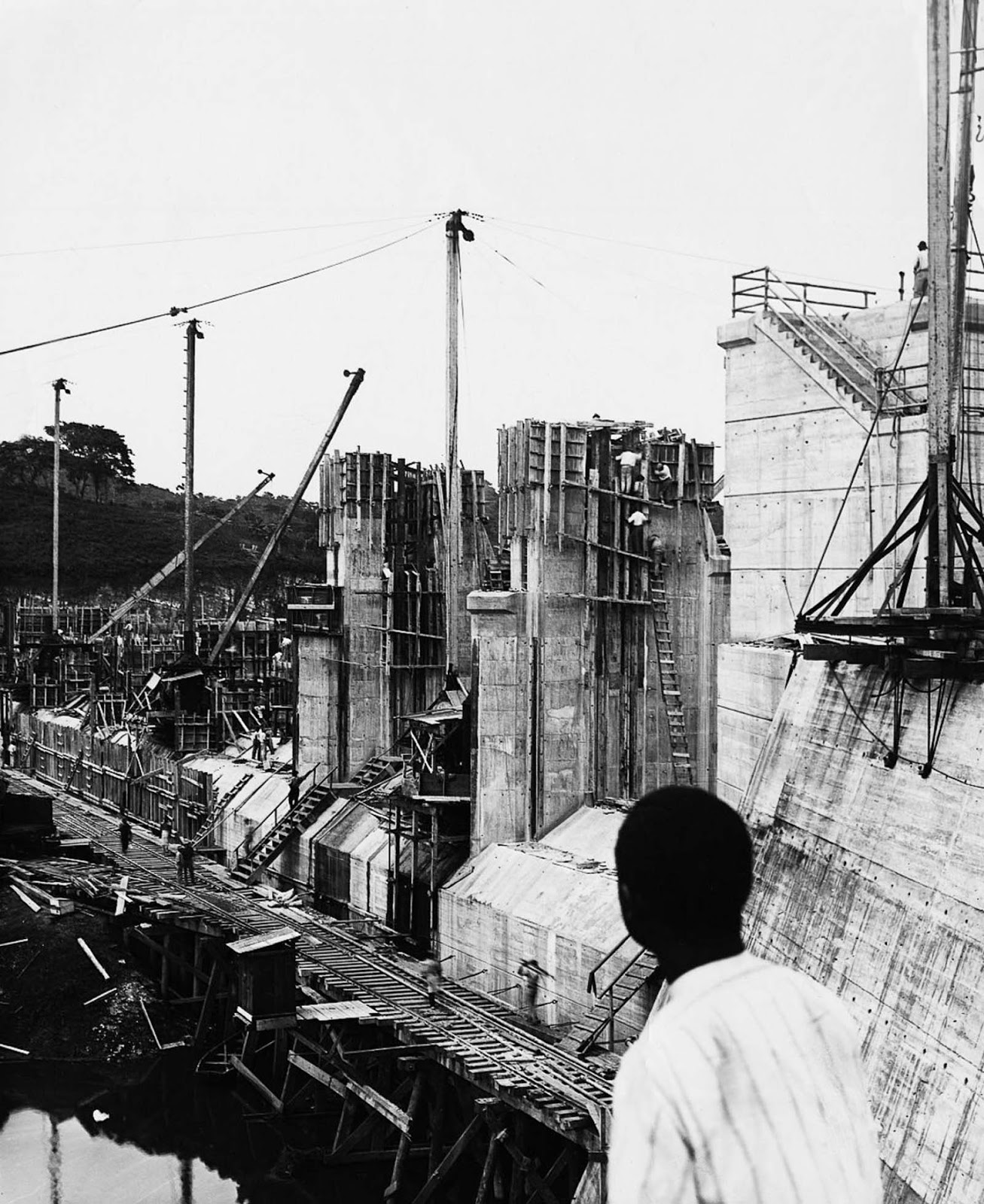

A survey of the isthmus was ordered and subsequently, a working plan for a canal was drawn up in 1529. The wars in Europe and the thirst for the control of kingdoms in the Mediterranean Sea put the project on permanent hold. Various surveys were made between 1850 and 1875 showed that only two routes were practical, one across Panama and another across Nicaragua. Inspired by the 10-year build of the Suez Canal, La Société Internationale du Canal Interocéanique obtained the rights in 1878 to build a version in Panama. The Colombian government, which controlled Panama, gave permission for the project. Ferdinand de Lesseps headed the fundraising. His success with the Suez Canal helped him raise millions for the new project. Once engineers got to work designing the canal, it became evident that this undertaking would be far more difficult than digging a sea-level ditch through a sandy desert. Though only about 40 miles wide at its narrowest point, the terrain of the isthmus was solid, rocky, and mountainous in places. The proposed canal route was intersected by powerful rivers which would need to be diverted. And most significantly, tropical diseases were a tremendous health hazard for laborers. Nevertheless, de Lesseps pushed ahead with an optimistic plan for a sea-level canal to be completed in only six years at an estimated cost of $120 million. A labor force of 40,000 men was assembled, composed almost entirely of workers from the West Indies, joined by engineers from France. In 1881, construction began. The project was a disaster. It quickly became obvious that a sea-level canal was impossible, and that building sets of locks leading to an elevated canal was the only workable plan. De Lesseps stubbornly stuck to the sea-level plan. Meanwhile, laborers and engineers were dying of malaria, yellow fever, and dysentery, and construction was frustrated by frequent floods and mudslides. By the time the raised-locks plan was adopted, it was already too late. An estimated 22,000 workers had died. The project was years behind schedule and hundreds of millions over budget. The company went bankrupt and collapsed, ruining 800,000 investors. De Lesseps was convicted of fraud and maladministration in 1893 and died in disgrace two years later. Following the deliberations of the U.S. Isthmian Canal Commission and a push from President Theodore Roosevelt, the U.S. purchased the French assets in the canal zone for $40 million in 1902. When a proposed treaty over rights to build in what was then a Colombian territory was rejected, the U.S. threw its military weight behind a Panamanian independence movement, eventually negotiating a deal with the new government. On November 6, 1903, the United States recognized the Republic of Panama, and on November 18 the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty was signed with Panama, granting the U.S. exclusive and permanent possession of the Panama Canal Zone. In exchange, Panama received $10 million and an annuity of $250,000 beginning nine years later. The treaty, negotiated by U.S. Secretary of State John Hay and French engineer Philippe-Jean Bunau-Varilla, was condemned by many Panamanians as an infringement on their country’s new national sovereignty. Contending with the same disease problems as the French, the Americans embarked on an aggressive mosquito extermination campaign. (The link between malaria and mosquitoes was still a very new theory.) This drastically reduced the instances of sickness and improved productivity. After a few years contending with inadequate machinery and infrastructure, excavation ramped up, and the canal began to take shape. The Gatun Dam was built across the Changres River, creating Gatun Lake, the largest manmade lake at the time. The lake stretches across half the span of the isthmus, carrying ships 21 miles in their traversal. Massive sets of locks were constructed at the Atlantic and Pacific ends of the canal. These 110-foot-wide locks allowed ships to pass through a series of chambers with adjustable water levels, stepping up to the elevation of Gatun Lake and the canal, 85 feet (26 meters) above sea level. The greatest effort, though, was the Culebra Cut — a nearly eight-mile carving through the Culebra mountain ridge, which reached 210 feet (64 meters) above sea level. 27,000 metric tons of dynamite were used to blast apart over 100 million cubic yards of earth, which were carted away with steam shovels and trains. Due to a misjudgment of the composition of the geological strata, the excavation was plagued by unpredictable landslides, which sometimes took months to clear. By the time the cut was completed in 1913, the summit had been lowered from 210 feet (64 meters) above sea level to 39 (12 meters). On Dec. 10, 1913, there was finally a traversable water route between the two oceans. On Jan. 7, 1914, the French crane boat Alexandre La Valley made the first passage through the canal. Today, 4% of all world trade passes through the canal, around 15,000 ships every year. Plans are underway to build an additional set of wider locks, as well as a competing canal through Nicaragua. The largest toll ever charged for passage was $142,000 for a cruise ship. The smallest was $0.36, for adventurer Richard Halliburton, who swam the canal through the locks in 1928. Bolstered by the addition of Madden Dam in 1935, the Panama Canal proved a vital component to expanding global trade routes in the 20th century. The transition to local oversight began with a 1977 treaty signed by U.S. President Jimmy Carter and Panama leader Omar Torrijos, with the Panama Canal Authority assuming full control on December 31, 1999. Recognized by the American Society of Civil Engineers as one of the seven wonders of the modern world in 1994, the canal hosted its 1 millionth passing ship in September 2010. (Photo credit: Bettmann / Corbis / Getty). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe