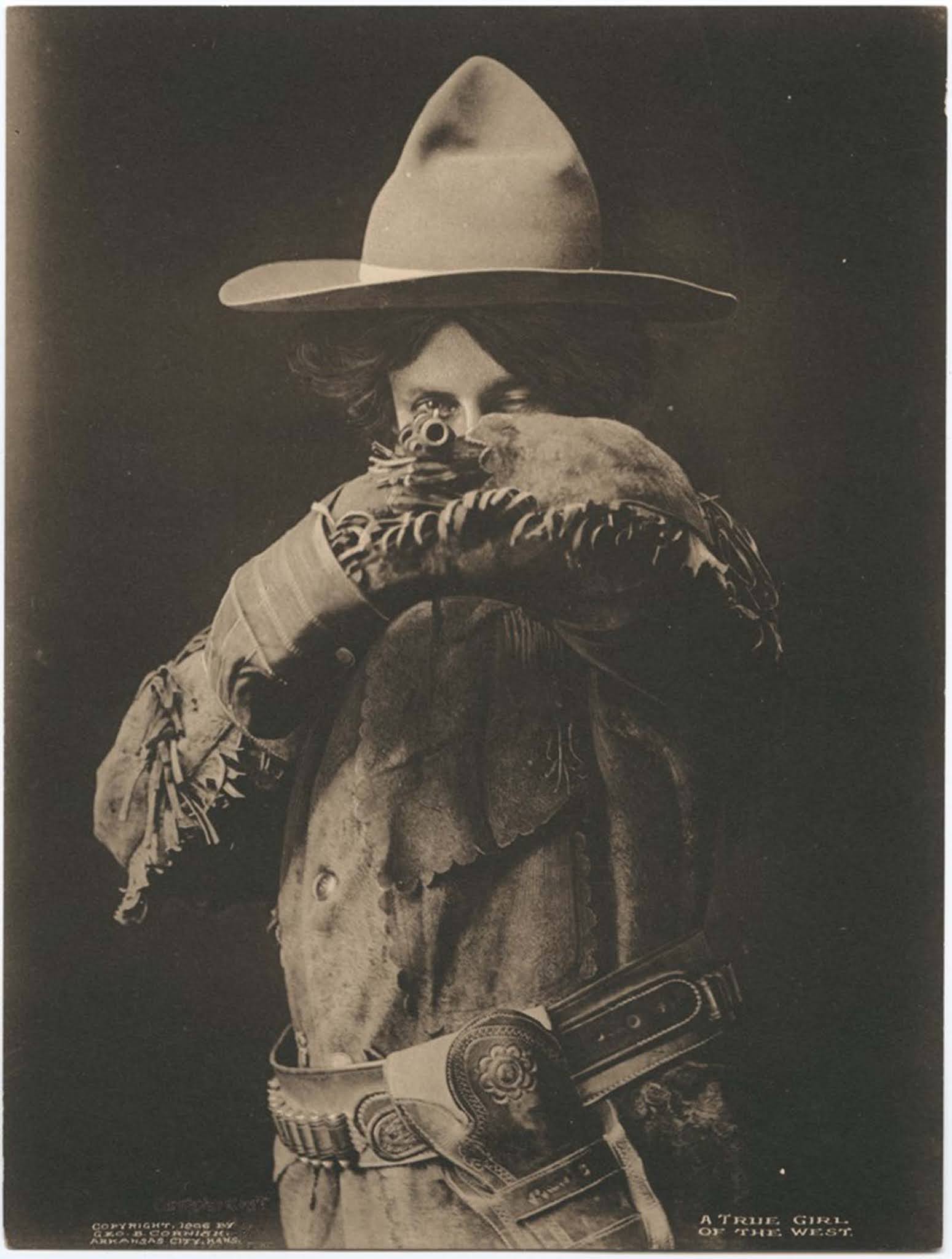

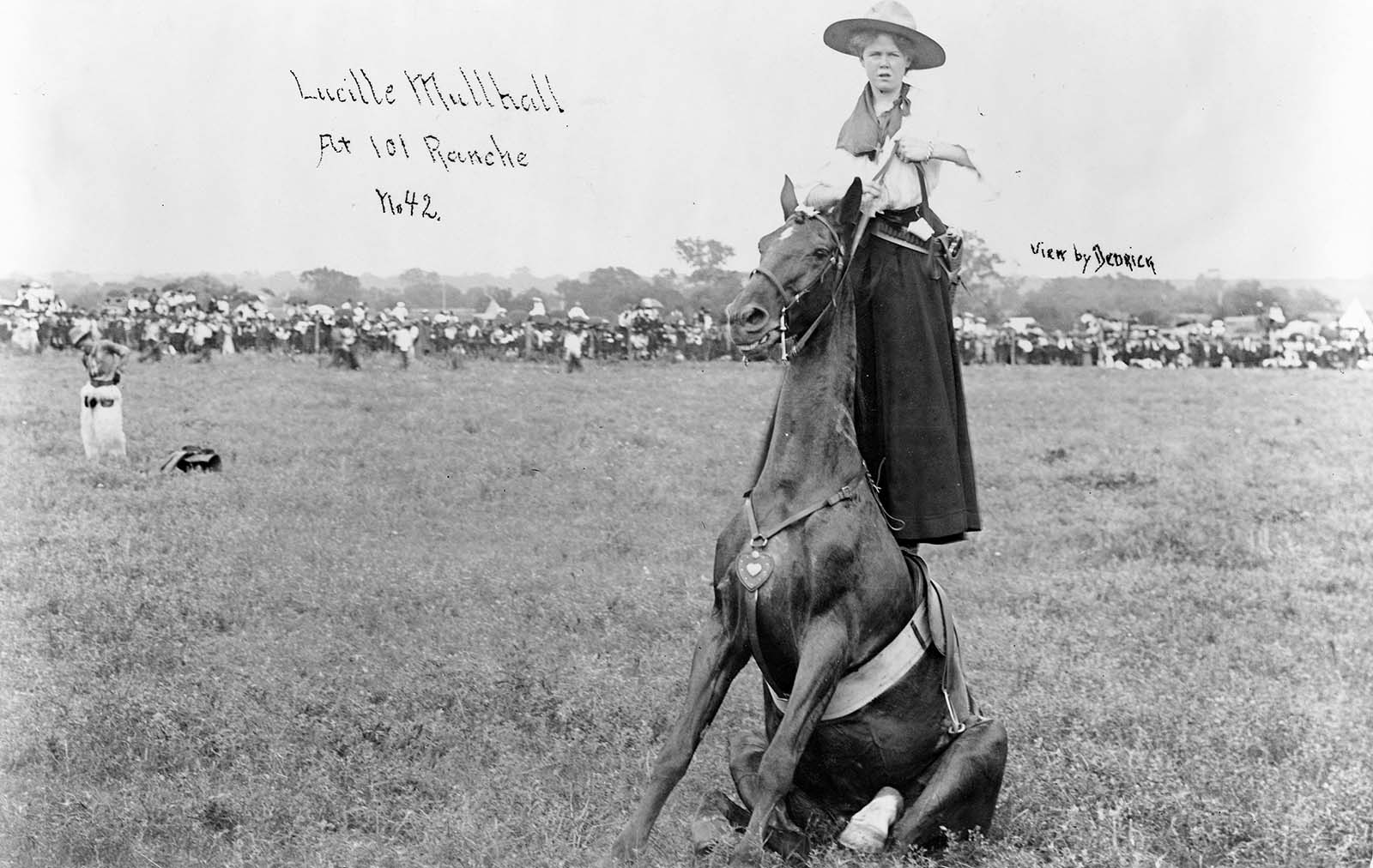

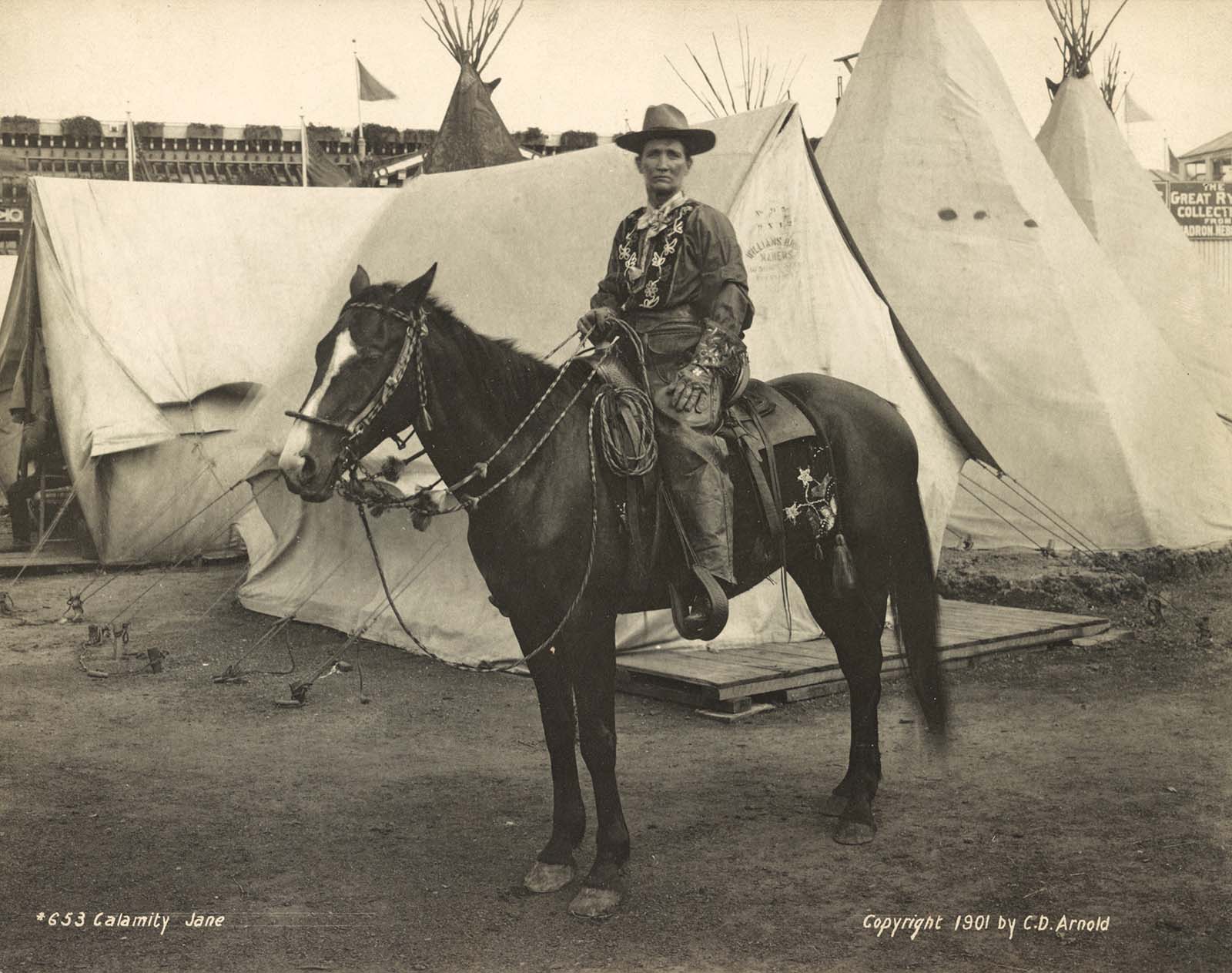

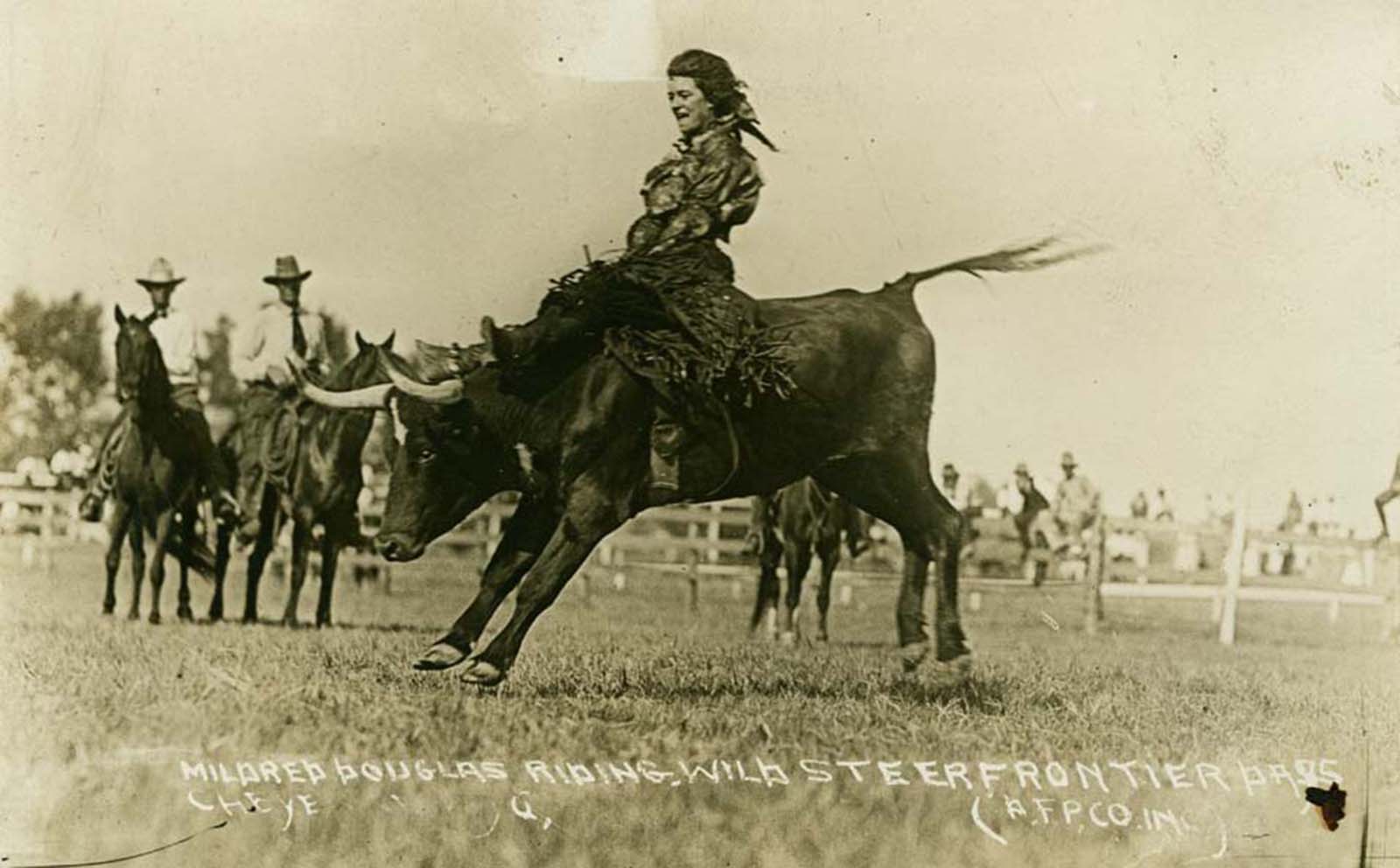

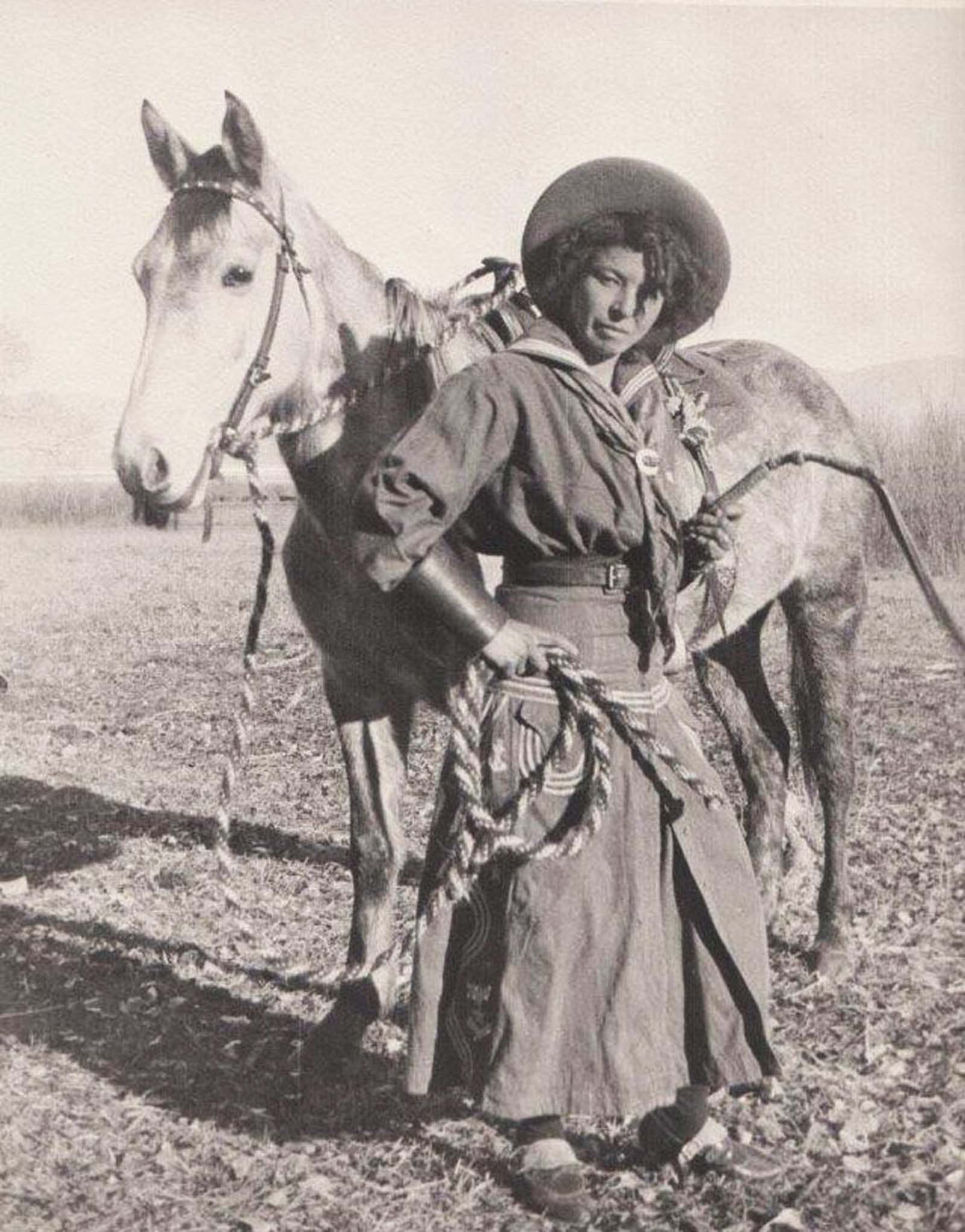

Before anyone ever heard the word “cowgirl,” there were women who ventured west. Most traveled with their families on covered wagons, beginning in the 1840s. They moved from crowded eastern cities to settle in western states such as Kansas, Nebraska, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah. Some wagon trains eventually went even farther, to California, Oregon, Idaho, and Washington. After the Civil War, more and more people sought new lives in the West. For nearly thirty years, from the 1840s to the late 1860s, the largest migration in the history of the country took place. The Homestead Act of 1860 mandated that 160 acres could be claimed in the west by men as well as women as long as they were twenty-one and unmarried. Though men by far outnumbered women in the early years, by 1870, there were 172,00 women over the age of twenty out west, compared to 385,00 men. While back east most women lived within society’s traditional rules, pioneer women had to adapt to survive the harsh circumstances of their journey and new surroundings. Many began to take on chores formerly done only by men. Wives, widows, mothers, and daughters on farms and ranches were helping to settle the western plains. Some of these women homesteaders learned to master the skills of riding horses, roping cattle and other animals, and shooting a gun when necessary. Pioneer Nannie Alderson, who settled in Montana, believed that “the new country offered greater personal liberty than the old.” One new freedom for women that grew out of the pioneering way of life involved a change in wardrobe. In those days, women rarely wore pants, and when riding horses, they sat sidesaddle. Their skirts kept them from riding like men, and in any case, it was not considered “ladylike” to do so. One early pioneer woman advised against observing customary attire and riding style while traveling to the West: “Sidesaddles should be discarded, women should wear hunting frocks, loose pantaloons, men’s hats, and shoes, and ride the came as men,” she wrote. The work of settling the new frontier was leading many women to abandon (or at least some of the time) the constricting, traditional mode of dress. Ranch woman and photojournalist Evelyn Cameron wrote about her transition to buckaroo life in Montana and Wyoming in the 1880s. “For some twenty years past, there have been cowgirls on Western ranches who are the feminine counterparts of cowboys, riding in similar saddles, on similar horses, for the purpose of similar duties, which they do, in fact, efficiently perform. The abolition of the sidesaddle was naturally the first step towards the creation of the cowgirl… I was determined to ride astride. With a divided skirt, I found it a simple operation to mount into a cow saddle. So great at first was the prejudice against any divided garment in Montana that a warning was given to me to abstain from riding on the streets of Miles City lest I might be arrested!’ In 1840, pioneer Sally Skull was one of the first women in Texas to own her own ranch, the Circle S, which she stocked with wild horses and cattle she brought across the border from Mexico. Her nickname was Mustang Jan, and her horse’s name was Redbuck. Wearing men’s clothing, she drove freight wagons from Texas to Mexico during the Civil War. A marker in her memory states that “she was a sure shot with the rifle she carried on her saddle or the two pistols strapped to her waist.” A few women pioneers pretended to be men so they could live like cowboys. In 1867, Jo Monaghan traveled west by herself from Buffalo, New York. To reach her destination safely, she donned a pair of pants, a vest, and a hat, and passed herself off as a man. After settling down in Idaho, she found she liked doing ranch work. In part enjoying male privileges such as voting, and in part fearing the consequences of revealing her true identity, she kept her disguise. Only upon Jo’s death in 1904 was it discovered that she had pretended to be a man. The farther west ranchers moved, however, the tougher it could be. Independent women often faced suspicion and harsh judgment on the part of their neighbors. Such was the fate of Ellen Watson, of Sweetwater Valley, Wyoming. Called Cattle Kate, she was accused of rustling (stealing) livestock in 1889. Local cattle barons greedy for her land killed her before she could even defend herself in court. The Cheyenne Daily Reader described the doomed woman: “Of robust physique, she was a daredevil in the saddle, handy with a six-shooter and adept with the lariat and branding iron… She rode straddle (rather than sidesaddle], always had a vicious bronco for the mount, and seemed never to tire of dashing across the range.” A century later, historians found that Cattle Kate had been falsely accused of the crime and was innocent. The origins of the cowboy tradition come from Spain, beginning with the hacienda system of medieval Spain. This style of cattle ranching spread throughout much of the Iberian peninsula and later was imported to the Americas. Both regions possessed a dry climate with sparse grass, thus large herds of cattle required vast amounts of land to obtain sufficient forage. The need to cover distances greater than a person on foot could manage gave rise to the development of the horseback-mounted vaquero. Barbed wire, an innovation of the 1880s, allowed cattle to be confined to designated areas to prevent overgrazing of the range. In Texas and surrounding areas, increased population required ranchers to fence off their individual lands. In the north, overgrazing stressed the open range, leading to insufficient winter forage for the cattle and starvation, particularly during the harsh winter of 1886–1887, when hundreds of thousands of cattle died across the Northwest, leading to the collapse of the cattle industry. By the 1890s, barbed-wire fencing was also standard in the northern plains, railroads had expanded to cover most of the nation, and meatpacking plants were built closer to major ranching areas, making long cattle drives from Texas to the railheads in Kansas unnecessary. Hence, the age of the open range was gone and large cattle drives were over. Since the closing of the prairie in the early 1900s, the term has come to refer to anyone who works on a ranch or takes part in traditional demonstrations of cowboy skills, known as rodeos. (Photo credit: Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons / Article based on The Cowgirl Way: Hats Off to America’s Women of the West by Holly George-Warren). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe