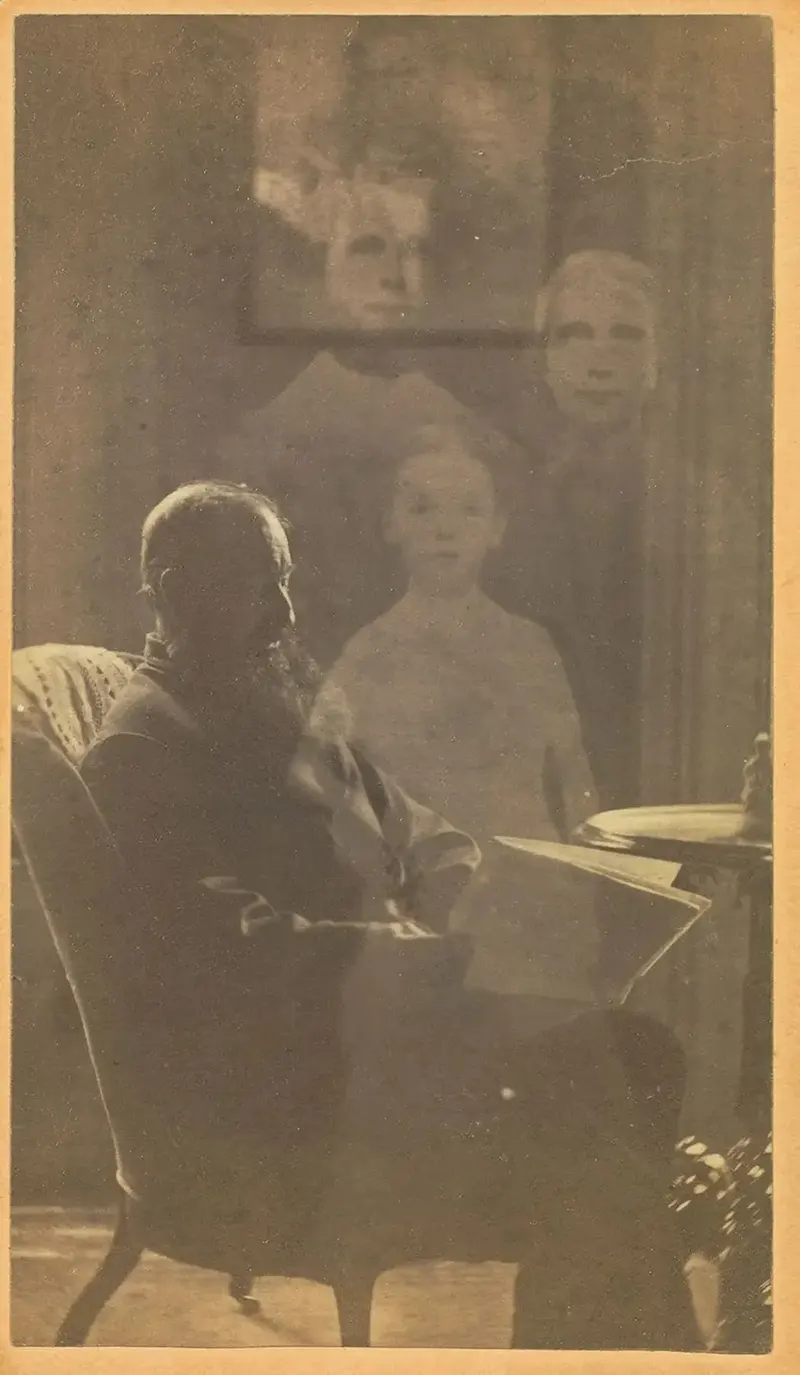

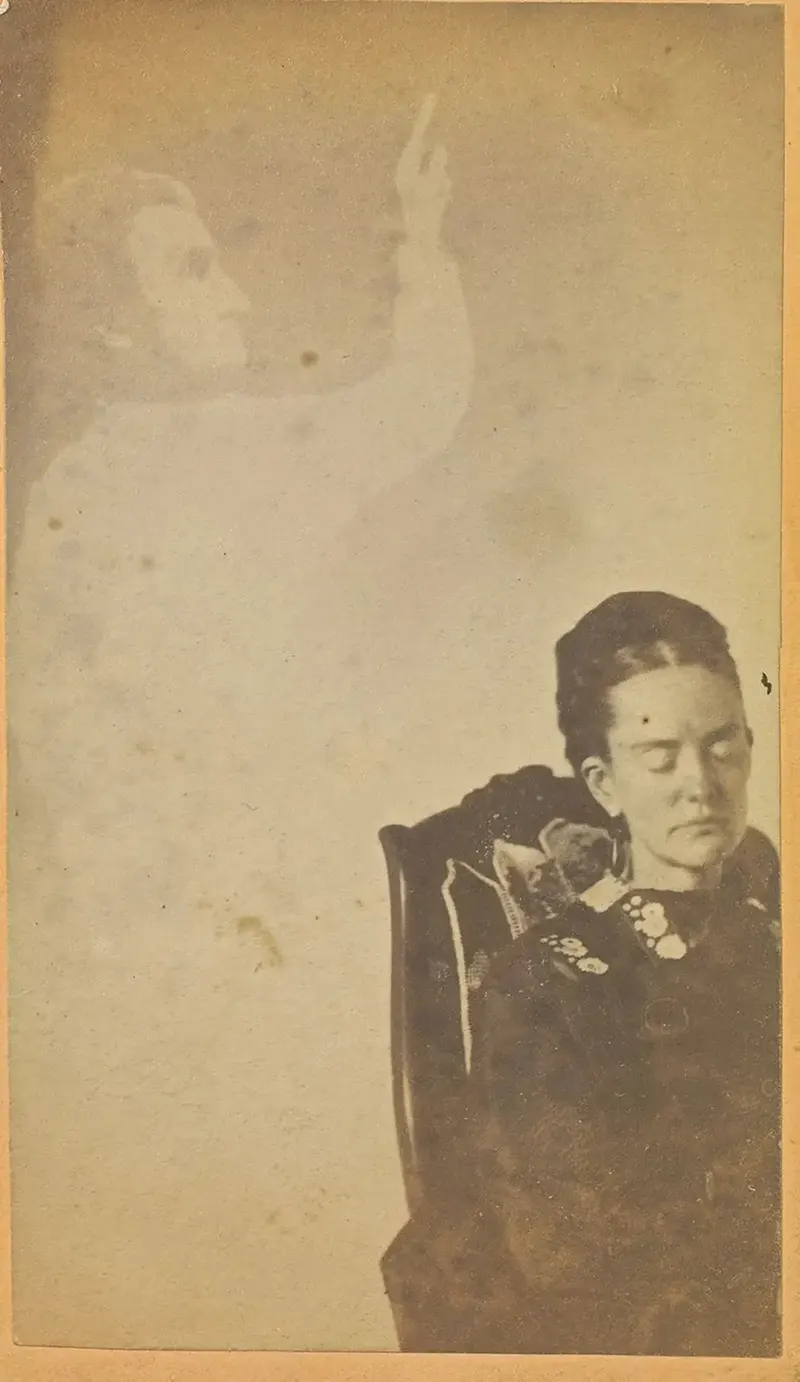

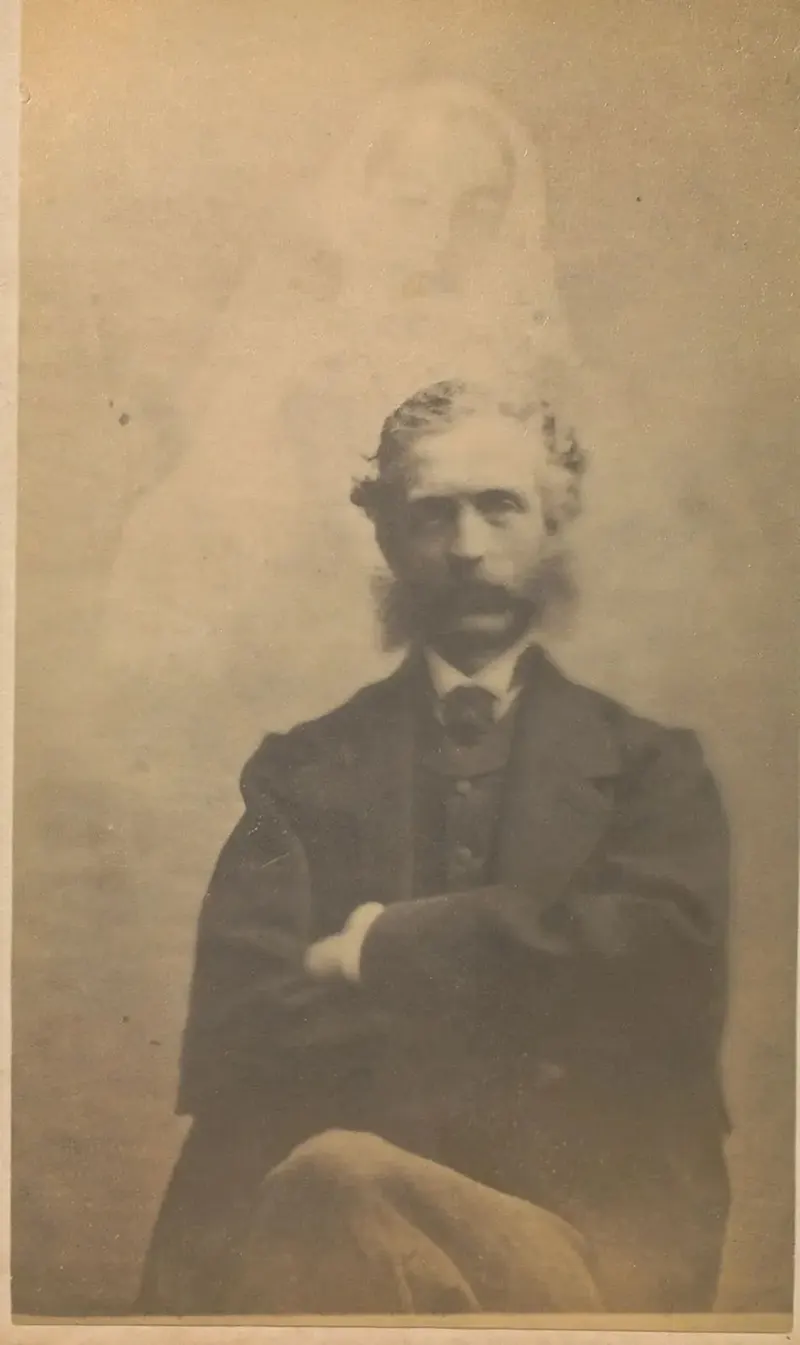

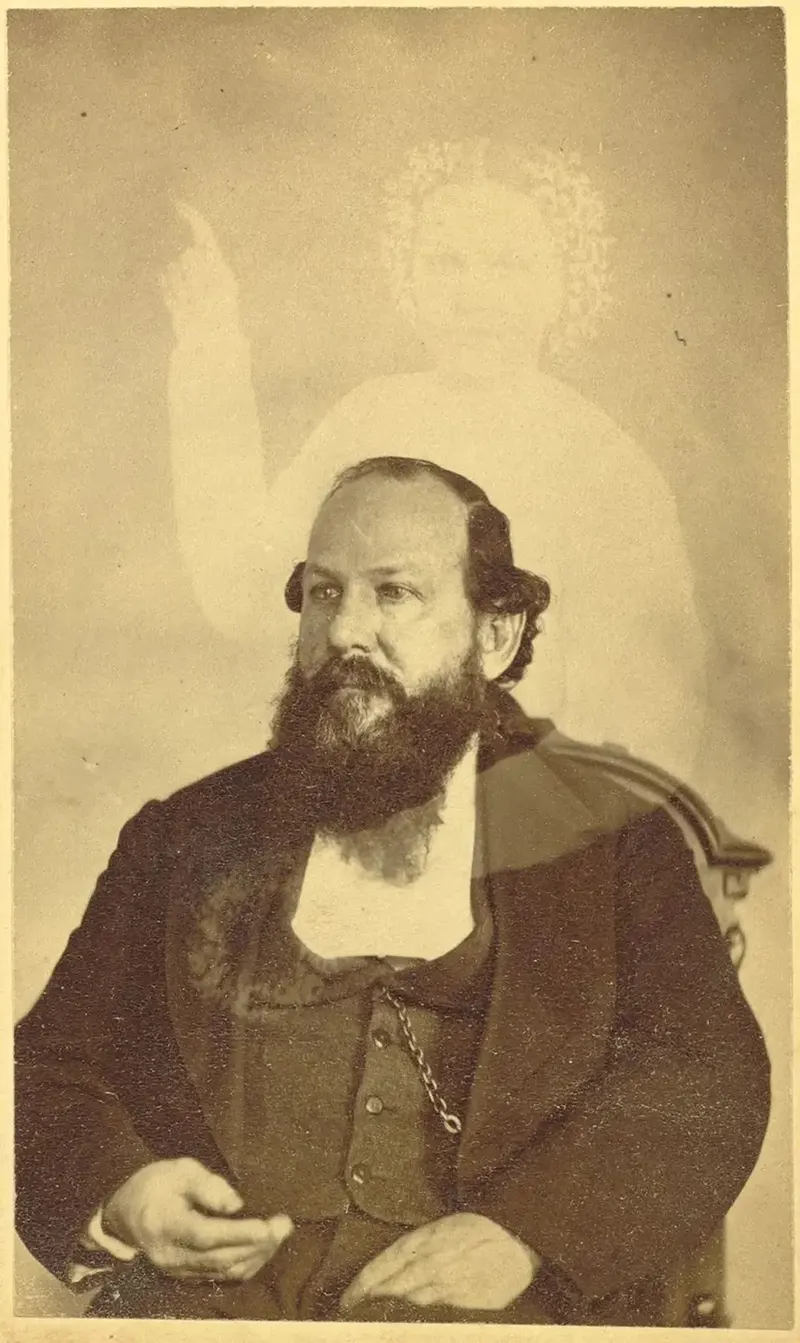

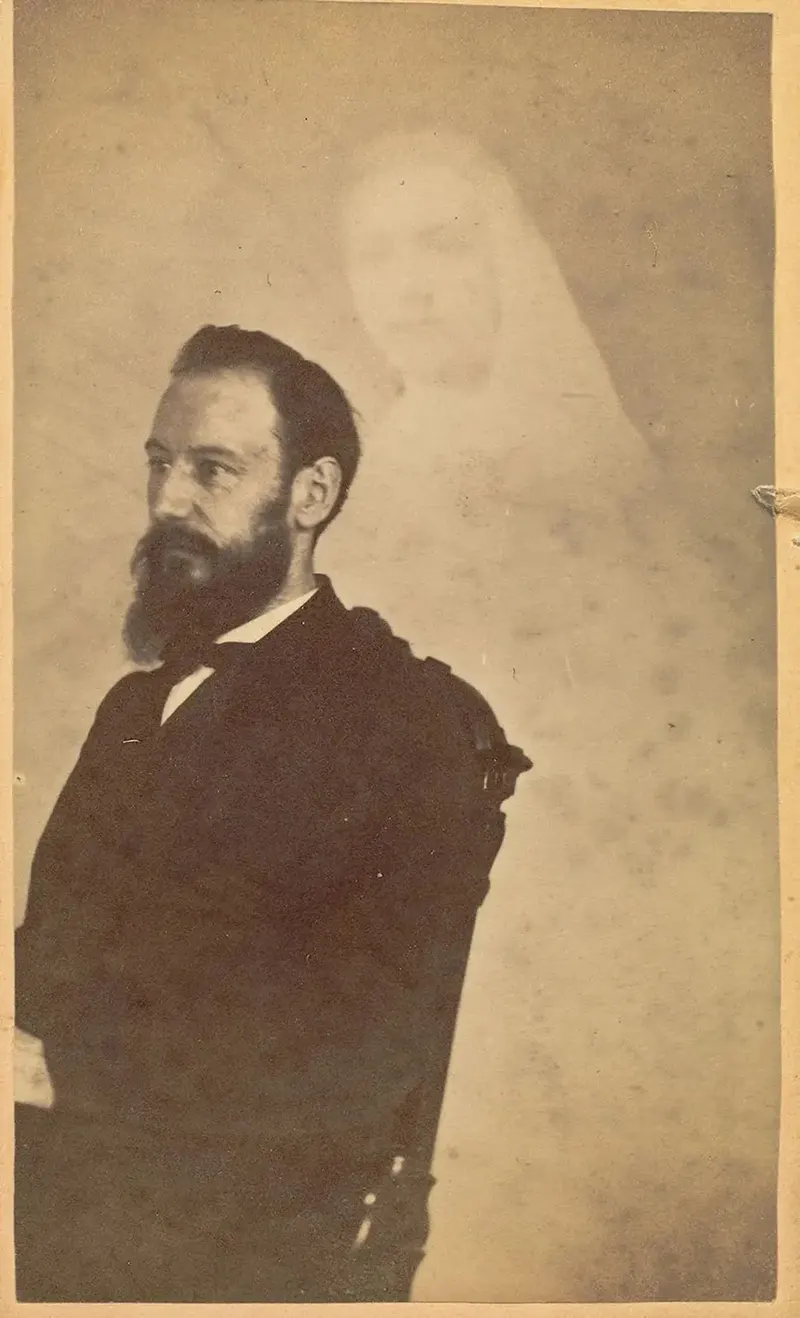

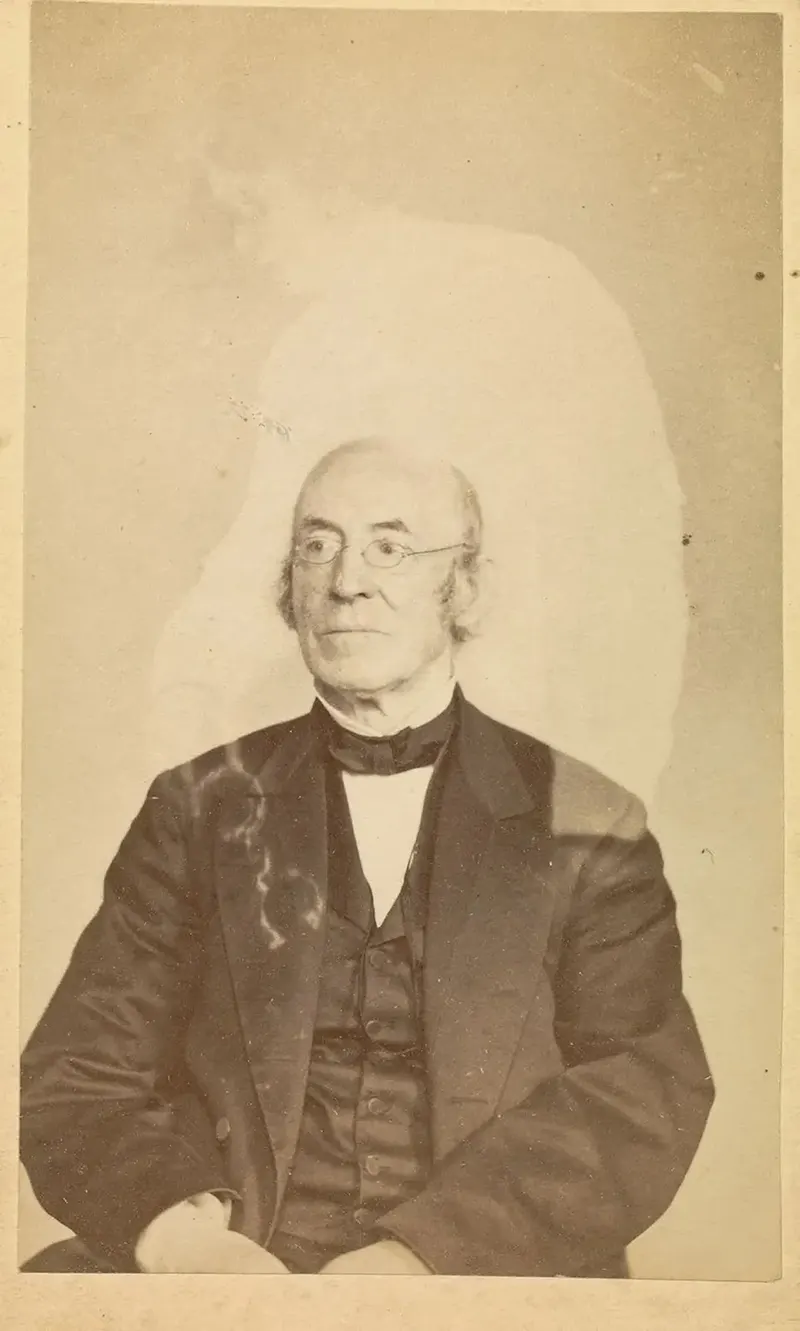

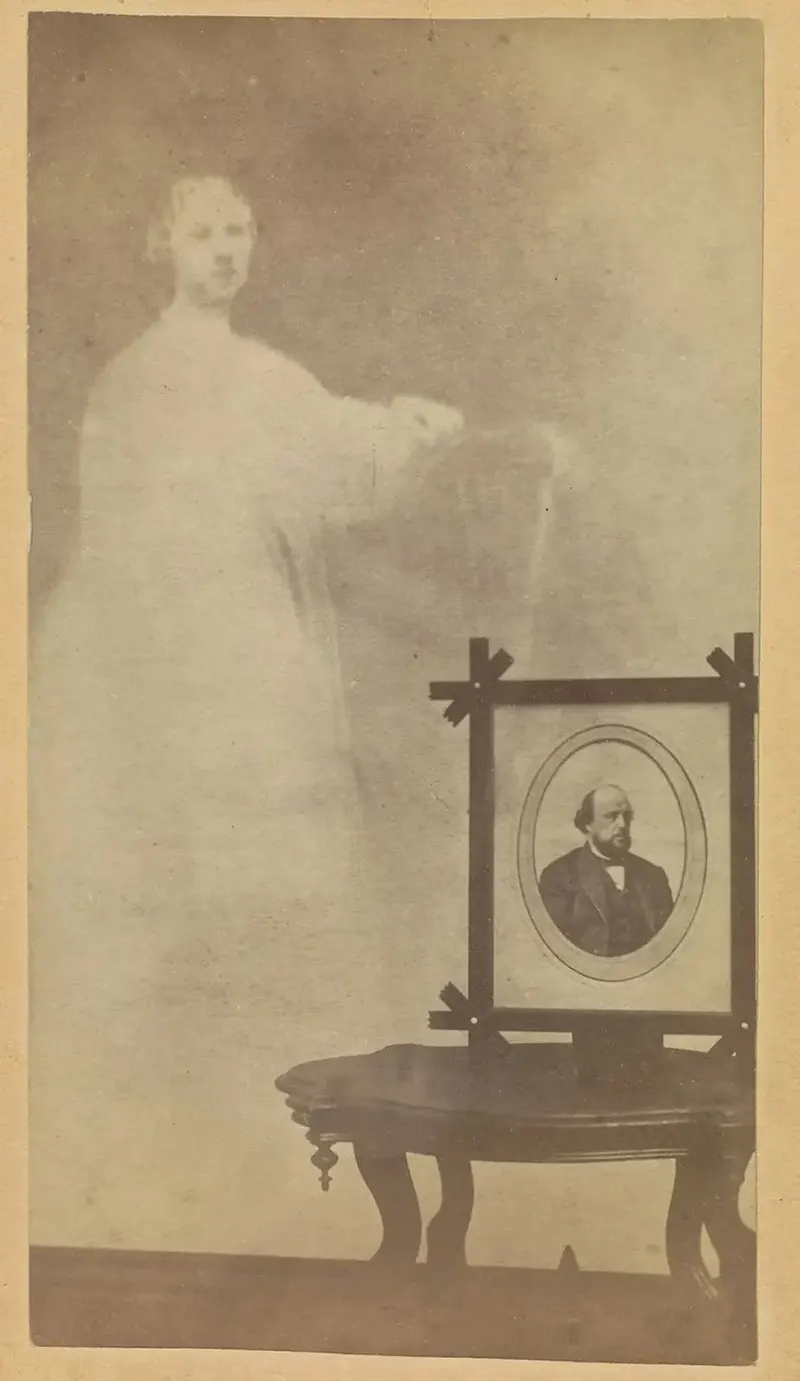

According to Owen Davies in The Haunted: A Social History of Ghosts, ghost photography started with photographic experimentation using people standing in front of and behind glass windows or noting that the long exposures required at the time would often result in transparent images when people or animals left the frame during the exposure. Sir David Brewster, in 1856, recognized that these effects could be used to deliberately create ghostly pictures. The London Stereoscopic Company decided to use Brewster’s idea and created a series of images called “The Ghost in the Stereoscope”. But it was not until glass plate negatives were used circa 1859, making double images possible, that spirits began to regularly appear in photographs. The coming together of photography and spirit allied modern technology to ancient belief and apparatus to apparitions, reconciling reason to religion and thereby confirming conviction. They also united two expressions of faith: one in the existence of invisible realities, the other in the camera’s indifferent eye, and the unerring ability to arrest the truth. Spirit, unlike any other subject matter that the camera would survey, drew attention to the paradox of photography’s double identity: at one and the same time an instrument for scientific enquiry into the visible world and, conversely, an uncanny, almost magical process able to conjure up the semblance of shadows and, with it, supernatural associations. It was the American William H. Mumler, however, who truly established the practice of spirit photographs in the 1860s. In 1862, Mumler published a photograph of what was purportedly the spirit of his cousin, who had died 12 years earlier. The media sensation that this caused, led Mumler to leave engraving and to begin a successful business as a “Spirit Photographic Medium”, which he set up in New York and Boston servicing those hoping to find a supernatural connection with relatives killed in the American Civil War. One of Mumler’s most famous images is a photograph of Mary Todd Lincoln posed with the purported spirit of her assassinated husband. The apparent spirits that Mumler had captured were double exposures of previous clients from photographic plates that were improperly cleaned. In 1869, Mumler’s fraud was discovered and he was charged. He was acquitted, however, despite the evidence provided that one of his so-called spirits was shown to be still alive. P.T. Barnum, who testified against Mumler, was one of his outspoken critics, declaring he was taking advantage of people’s grief. Mumler later moved on to doing regular photography. The first in Europe, Frederick Hudson in London and Edouard Isidore Buguet in Paris, emerged in the early 1870s. This early, essentially commercial phase of spirit photography was marked by several court cases that, depending on their verdicts, either fostered or constrained the development of the practice. In 1891 one of the most famous spirit photographs was taken by Sybell Corbet. She took a photo of the library at Combermere Abbey in Cheshire, England in which appeared the “…faint outline of a man’s head, collar, and right arm”. The figure was believed to be the ghost of Lord Combermere who had recently died and was being buried at the time the photo was taken. Because the exposure was one hour, it was believed by skeptics that someone, possibly a servant, had walked into the room and paused, causing the ghostly outline. As is often the case with spiritualist phenomena, the most intense phases of activity corresponded to or followed periods of war, when victims’ families were willing to do anything to have one last contact with their loved ones. This was particularly true of the United States after the Civil War and France after the War of 1870 and the Commune.

(Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / William Mumler / Courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe