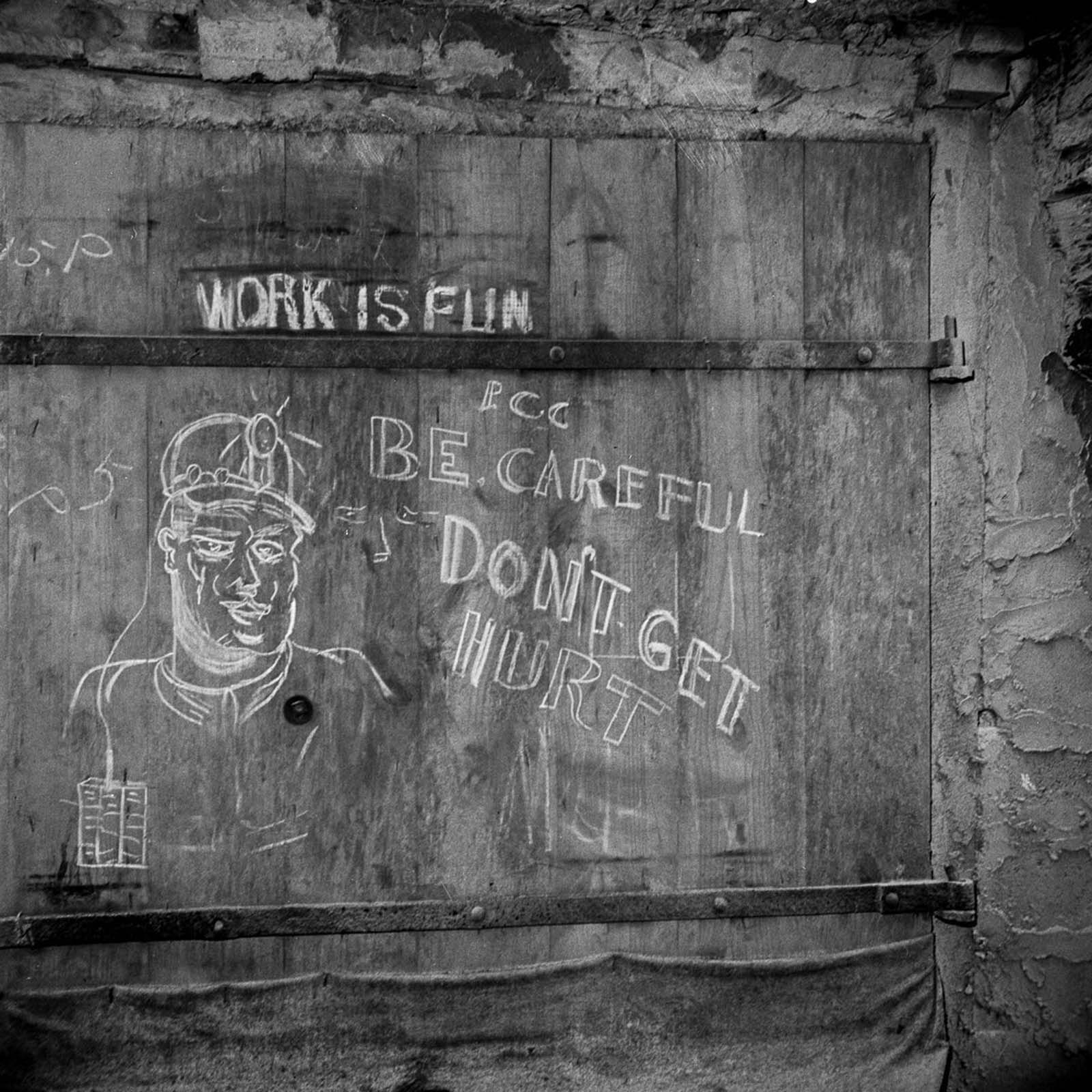

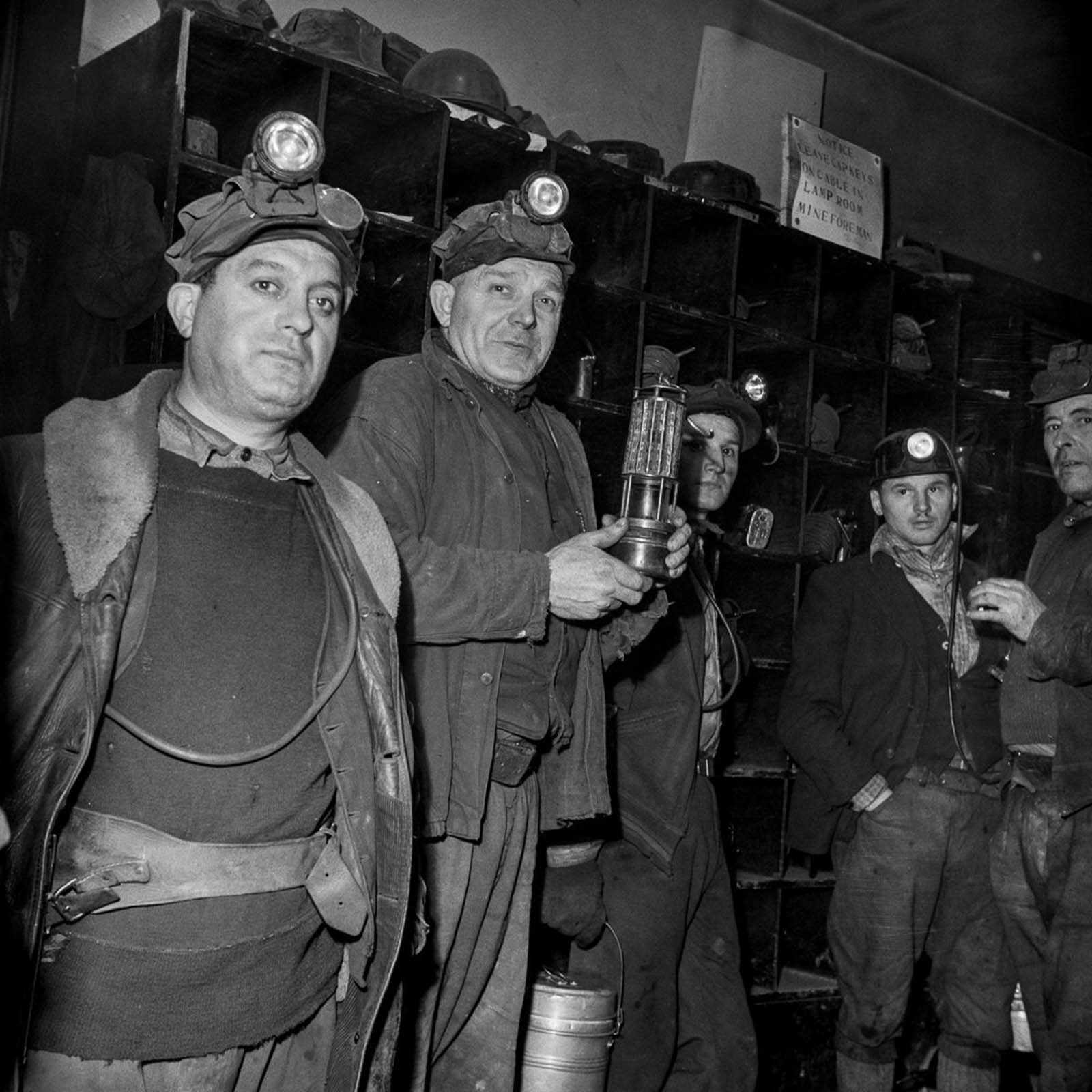

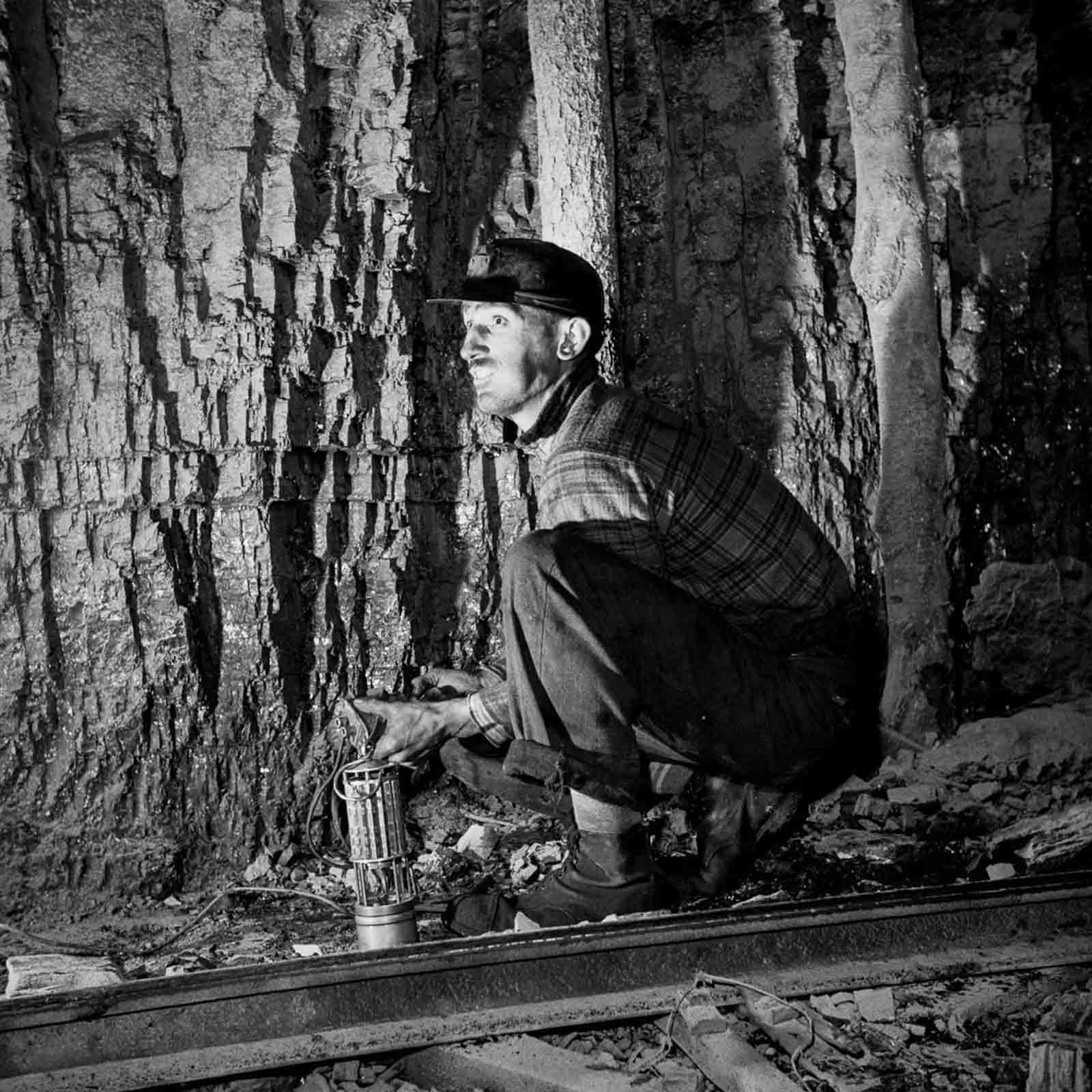

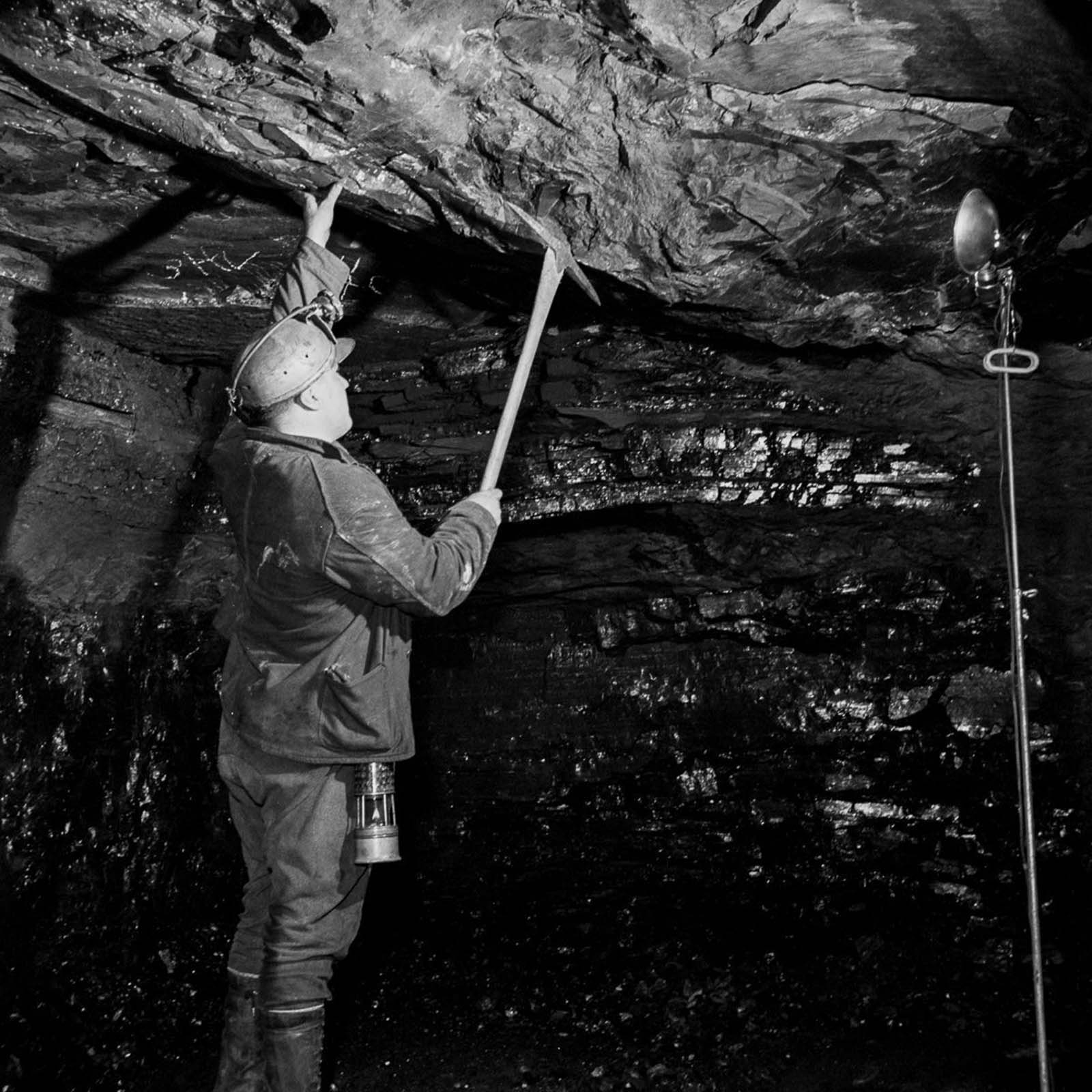

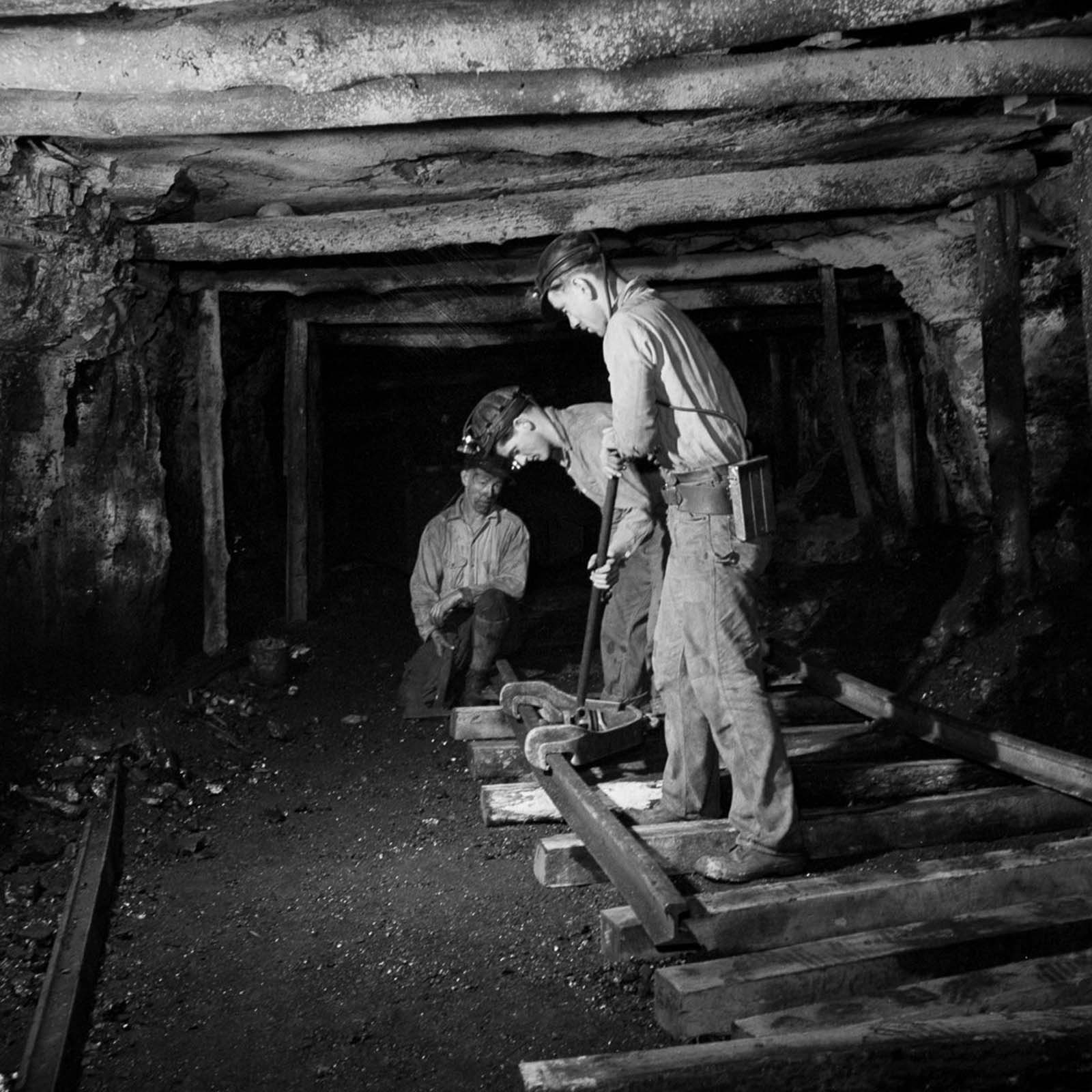

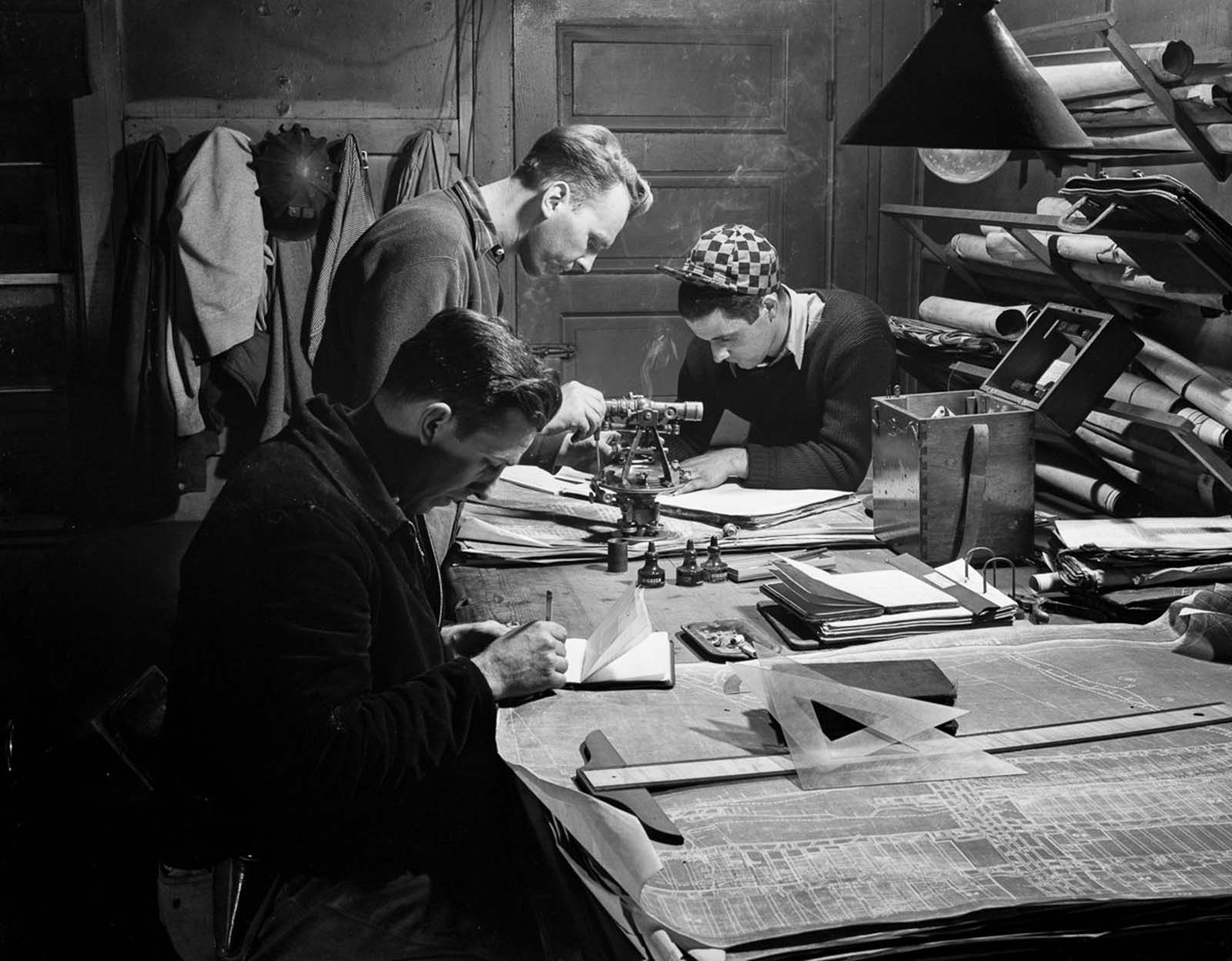

The pictures collected in this article were taken by John Collier, an Office of War Information photographer, and capture the gritty life of miners working in Montour No. 4 Mine of the Pittsburgh Coal Company. Collier documented the underground life of the miners, laying tracks and deploying the machinery, drilling, blasting with dynamite while being careful from possible collapses. Vesta Montour No. 4 Mine was once the largest bituminous coal mine in the world. The mine was opened circa 1903, was closed in 1957, was temporarily re-opened in 1960, and permanently closed in 1984.

Bituminous coal was first mined in Pennsylvania at “Coal Hill” (Mount Washington), just across the Monongahela River from the city of Pittsburgh. The coal was extracted from drift mines in the Pittsburgh coal seam, which outcrops along the hillside and transported by canoe to the nearby military garrison. By 1830, the city of Pittsburgh consumed more than 400 tons per day of bituminous coal for domestic and light industrial use. Development of the anthracite coalfields in eastern Pennsylvania had progressed to the point where “hard coal” had captured the eastern markets. Consequently, bituminous coal production in western Pennsylvania grew principally with western population growth, expansion and development of rail and river transportation facilities to the west, and the emergence of the steel industry. Towards the last half of the nineteenth century, the demand for steel generated by the explosive growth of the railroad industry and shipbuilding concerns began to further impact bituminous coal production in western Pennsylvania. The early mines used the so-called “room-and-pillar” method, a mining system in which the mined material is extracted across a horizontal plane, creating horizontal arrays of rooms and pillars. Mines relied on manual labor to cut the coal at the working face and the coal was hauled from the mine by horse and wagon. Later on, as documented in these pictures, many room-and-pillar mines use mechanized continuous mining machines to cut the coal and a network of conveyors that transports the coal from the working face to the surface.

(Photo credit: Library of Congress). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe