The accident caused the deaths of fourteen people (three crewmen and eleven people in the building) and damage estimated at US$1 million (at the time), although the building’s structural integrity was not compromised. That day, Lieutenant Colonel William F. Smith Jr. was piloting a B-25 Mitchell bomber on a routine personnel transport mission from Bedford Army Air Field in Massachusetts to Newark Metropolitan Airport in New Jersey. Smith asked for clearance to land, but he was advised of zero visibility Proceeding anyway, he became disoriented by the fog and turned right instead of left after passing the Chrysler Building.

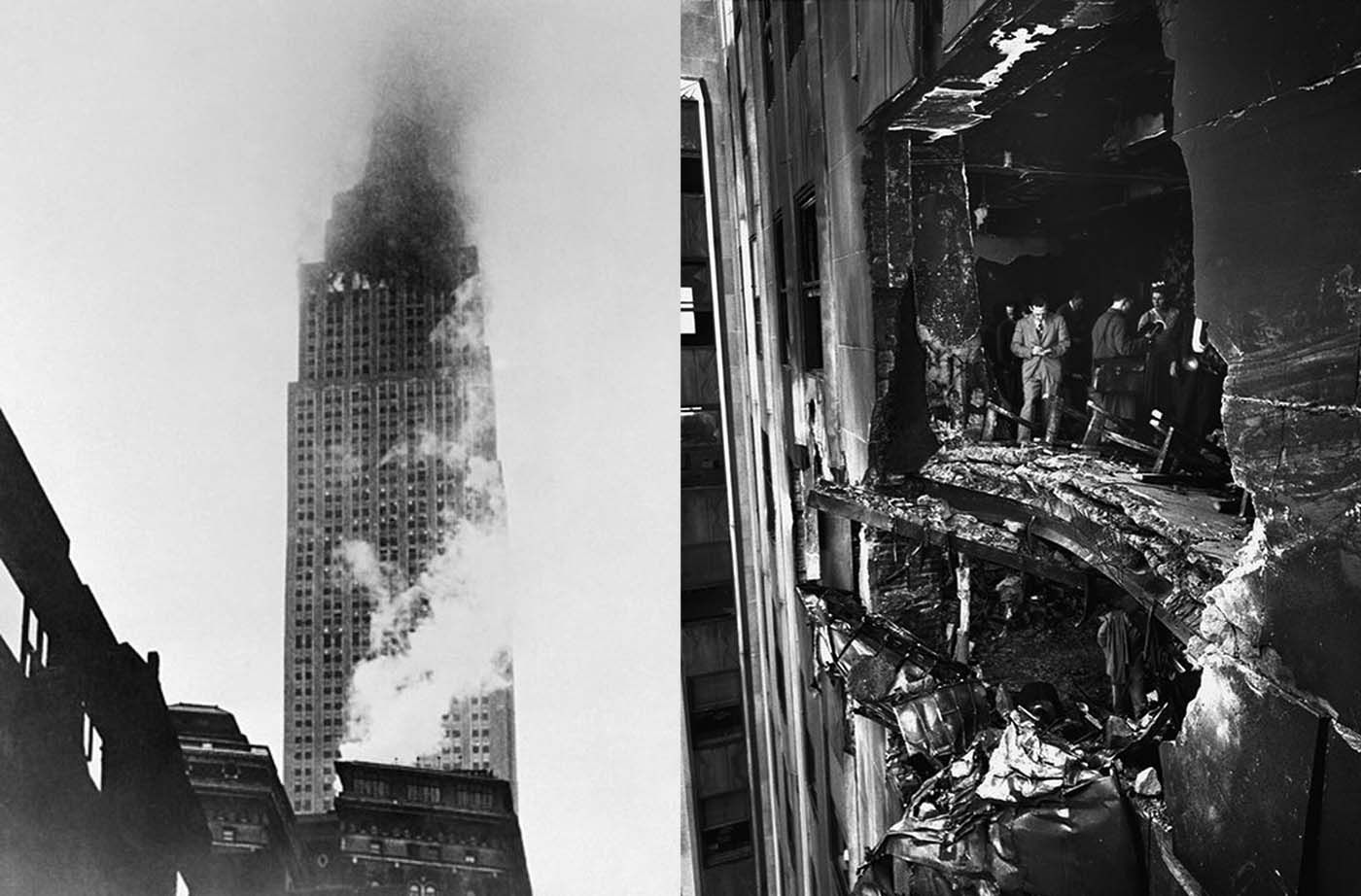

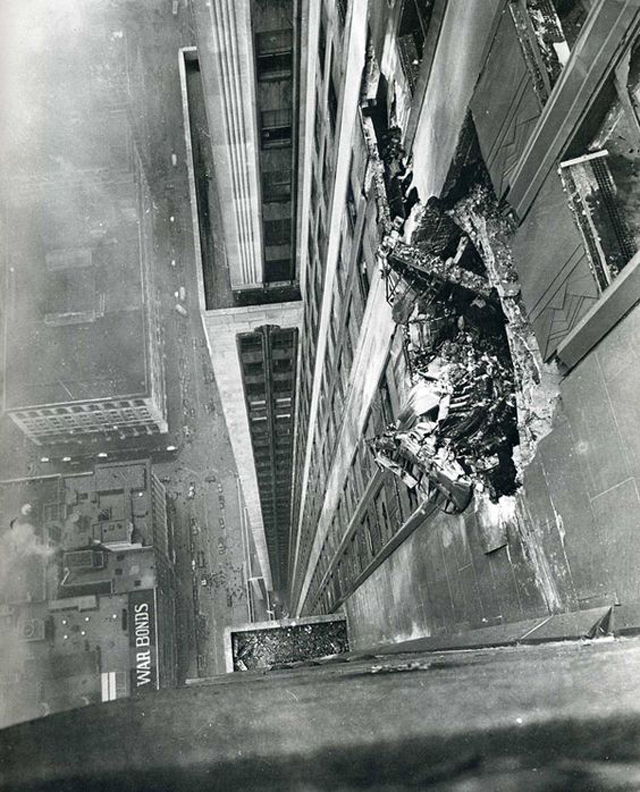

At 9:40 a.m., the aircraft crashed into the north side of the Empire State Building, between the 78th and 80th floors, making an 18-by-20-foot (5.5 m by 6.1 m) hole in the building. One engine shot through the south side opposite the impact, flew as far as the next block, dropped 900 feet (270 m), landed on the roof of a nearby building, and caused a fire that destroyed a penthouse art studio. The other engine and part of the landing gear fell down an elevator shaft. The resulting fire was extinguished in 40 minutes. Between 50 and 60 sightseers were on the 86th-floor observation deck when the crash happened. Fourteen people were killed: Colonel Smith, Staff Sergeant Christopher Domitrovich, and Navy Aviation Machinist’s Mate Albert Perna, who was hitching a ride, and eleven civilians in the building. Perna’s body was not found until two days later when search crews discovered that it had entered an elevator shaft and fallen to the bottom. The other two crewmen were burned beyond recognition. Elevator operator Betty Lou Oliver was thrown from her elevator car on the 80th floor and suffered severe burns. First aid workers placed her on another elevator car to transport her to the ground floor, but the cables supporting that elevator had been damaged in the incident, and it fell 75 stories, ending up in the basement. Oliver survived the fall due to the softening cushion of air created by the falling elevator car within this elevator shaft, however, she suffered a broken pelvis, back, and neck when rescuers found her amongst the rubble. This remains the world record for the longest survived elevator fall. Despite the damage and deaths, the building was open for business on many floors on the next Monday morning, less than 48 hours later. The crash spurred the passage of the long-pending Federal Tort Claims Act of 1946, as well as the insertion of retroactive provisions into the law, allowing people to sue the government for the accident.

Therese Fortier Willig, who was 20 years old at the time, worked for the Catholic Relief Services on the 79th floor: “In the other side of the office, all I could see was flames. Mr. Fountain was walking through the office when the plane hit the building and he was on fire — I mean, his clothes were on fire, his head was on fire. Six of us managed to get into this one office that seemed to be untouched by the fire and close the door before it engulfed us. There was no doubt that the other people must have been killed.” Gloria Pall worked for the United Service Organization’s headquarters on the 56th floor: “I was at the file cabinet and all of a sudden the building felt like it was just going to topple over,” Pall said. “It threw me across the room, and I landed against the wall. People were screaming and looking at each other. We didn’t know what to do. We didn’t know if it was a bomb or what happened. It was terrifying.”Therese Fortier Willig: “It was a very small universe at that point. You’re stuck there in an island, with fire all around us,” Willig said. “A couple of the women had passed out from the smoke, and I had a handkerchief in my pocket, and so I used that to cover my nose and my mouth to protect me from the fumes. And somebody had opened the window. And I’m sitting there, and I thought about my rings. And I thought I won’t be around to have them, someone else might as well have use out of them. So I took them off my fingers and threw them out the window.” “And all of a sudden here were firemen and they’re coming to rescue us, all dressed up in their raincoats, whatever they wear. t was just wonderful. We climbed out through the broken glass. I was just grateful to be alive.”

(Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / Library of Congress / Getty Images / New York Daily News Archive / Testimonies via NPR / Pinterest / Flickr). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe