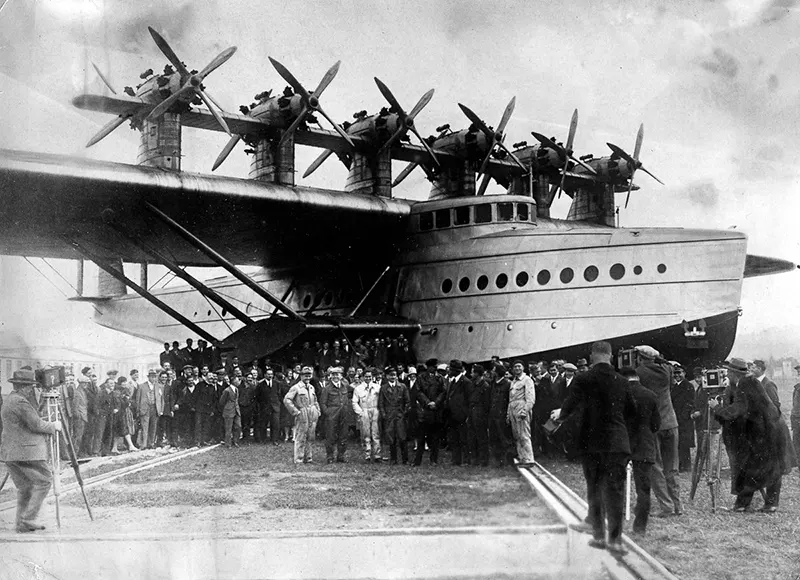

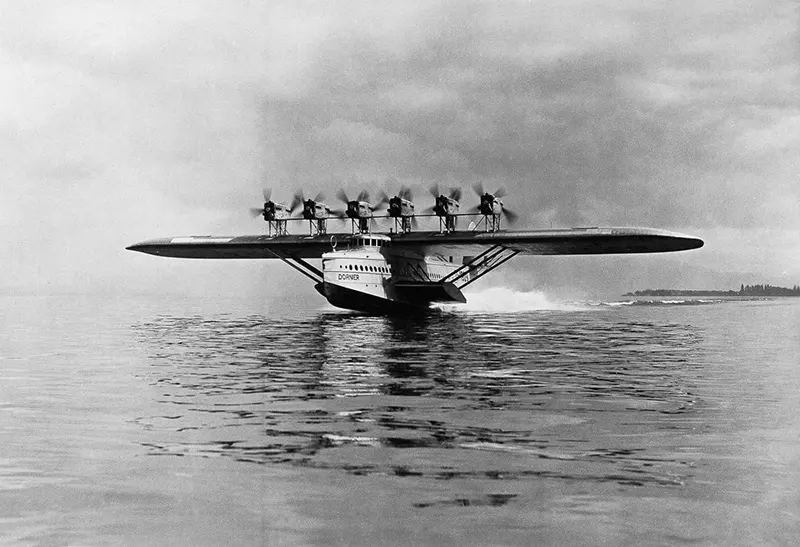

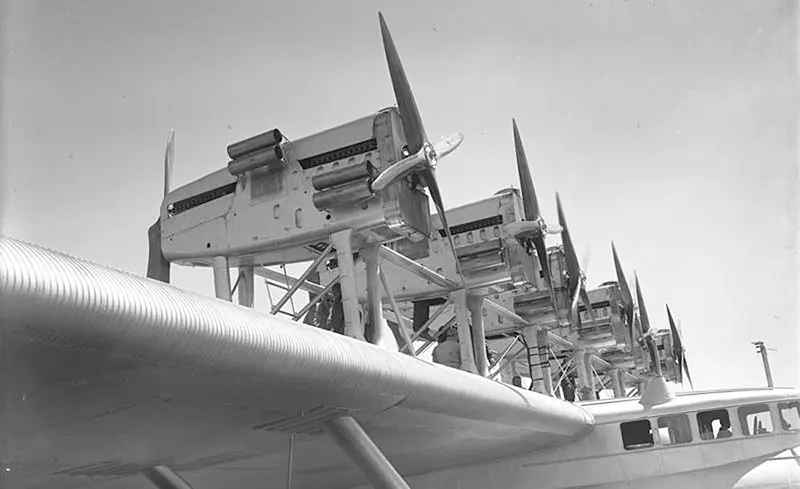

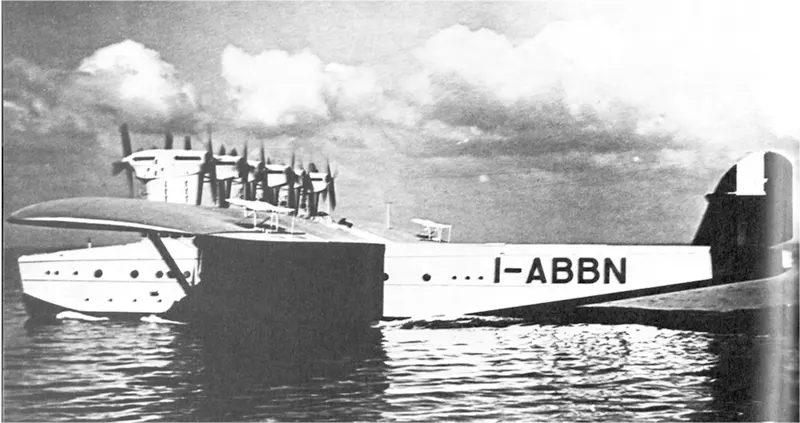

With a wingspan of 157 feet (48 meters) and length of 130 feet (40 meters), the Do X was powered by 12 engines and carried 169 passengers. First conceived by Claude Dornier in 1924, planning started in late 1925 and after over 240,000 work hours it was completed in June 1929. The Do X was a semi-cantilever monoplane and had an all-duralumin hull, with wings composed of a steel-reinforced duralumin framework covered in heavy linen fabric, covered with aluminum paint. It was initially powered by twelve 391 kW (524 hp) Siemens-built Bristol Jupiter radial engines in tandem push-pull configuration mountings, with six tractor propellers and six pushers mounted on six strut-mounted nacelles above the wing. The nacelles were joined by an auxiliary wing to stabilize the mountings. The air-cooled Jupiter engines were prone to overheating and could barely lift the Do X to an altitude of 425 m (1,394 ft). The engines were managed by a flight engineer, who controlled the 12 throttles and monitored the 12 sets of gauges. The pilot would relay a request to the engineer to adjust the power setting, in a manner similar to the system used on maritime vessels, using an engine order telegraph. Many aspects of the aircraft echoed nautical arrangements of the time, including the flight deck, which bore a strong resemblance to the bridge of a vessel. After completing 103 flights in 1930, the Do X was refitted with 455 kW (610 hp) Curtiss V-1570 “Conqueror” water-cooled V-12 engines. Only then was it able to reach the altitude of 500 m (1,600 ft) necessary to cross the Atlantic. Dornier designed the flying boat to carry 66 passengers on long-distance flights or 100 passengers on short flights. The luxurious passenger accommodation approached the standards of transatlantic liners. There were three decks. On the main deck was a smoking room with its own wet bar, a dining salon, and seating for the 66 passengers which could also be converted to sleeping berths for night flights. Aft of the passenger spaces was an all-electric galley, lavatories, and cargo hold. The cockpit, navigational office, engine control, and radio rooms were on the upper deck. The lower deck held fuel tanks and nine watertight compartments, only seven of which were needed to provide full flotation. Three Do Xs were constructed in total. The original operated by Dornier, and two other machines based on orders from Italy. The X2, named Umberto Maddalena (registered I-REDI), and X3, named Alessandro Guidoni (registered I-ABBN). The Italian variants were slightly larger and used a different powerplant and engine mounts. The Flugschiff (“flying ship”), as it was called, was launched for its first test flight on 12 July 1929, with a crew of 14. To satisfy skeptics, on its 70th test flight on 21 October there were 169 on board of which 150 were passengers (mostly production workers and their families, and a few journalists), ten were aircrew and nine were stowaways. The flight set a new world record for the number of people carried on a single flight, a record that would stand for 20 years. After a takeoff run of 50 seconds the Do X slowly climbed to an altitude of 200 m (660 ft). Passengers were asked to crowd together on one side or the other to help make turns. It flew for 40 minutes. To introduce the airliner to the potential United States market the Do X took off from Friedrichshafen, Germany, on 3 November 1930, under the command of Friedrich Christiansen for a transatlantic test flight to New York. The route took the Do X to the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, France, Spain, and Portugal. The journey was interrupted at Lisbon on 29 November, when a tarpaulin made contact with a hot exhaust pipe and started a fire that consumed most of the left wing. After sitting in Lisbon harbor for six weeks while new parts were fabricated and the damage repaired, the flying boat continued with several further mishaps and delays along the Western coast of Africa and by 5 June 1931 had reached the islands of Cape Verde, from which it crossed the ocean to Natal in Brazil. The flight continued north via San Juan to the United States, reaching New York on 27 August 1931, almost ten months after departing Friedrichshafen. The Do X and crew spent the next nine months there as its engines were overhauled, and thousands of sightseers made the trip to Glenn Curtiss Airport (now LaGuardia) for sightseeing tours. The Great Depression dashed Dornier’s marketing plans for the Do X, and it departed from New York on 21 May 1932 via Newfoundland and the Azores to Müggelsee, Berlin, where it arrived on 24 May and was met by a cheering crowd of 200,000. The Do X2 entered service in August 1931, and the X3 followed in May 1932. Both were initially based at the seaplane station at La Spezia, on the Ligurian Sea, and reassigned to various other bases during their service. Both orders originated with SANA, then the Italian state airline, but were requisitioned and used by the Italian Air Force primarily for prestige flights and public spectacles. Germany’s original Do X was turned over to Deutsche Lufthansa, the German national airline after the financially strapped Dornier company could no longer operate it. After a successful 1932 tour of German coastal cities, Lufthansa planned a Do X flight to Vienna, Budapest, and Istanbul for 1933. The voyage ended after nine days when the flying boat’s tail section tore off during a botched, overly-steep landing on a reservoir lake near Passau. The Do X remained an exhibit until being destroyed during World War II in a Royal Air Force air raid on the night of 23–24 November 1943. Fragments of the torn-off tail section are displayed at the Dornier Museum in Friedrichshafen. While never a commercial success, the Dornier Do X was the largest heavier-than-air aircraft of its time, and demonstrated the potential of an international passenger air service.

(Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / Flickr / Britannica / Library of Congress / Mashable.com / Getty / ullstein bild / Huffington Post / Bundesarchiv). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe