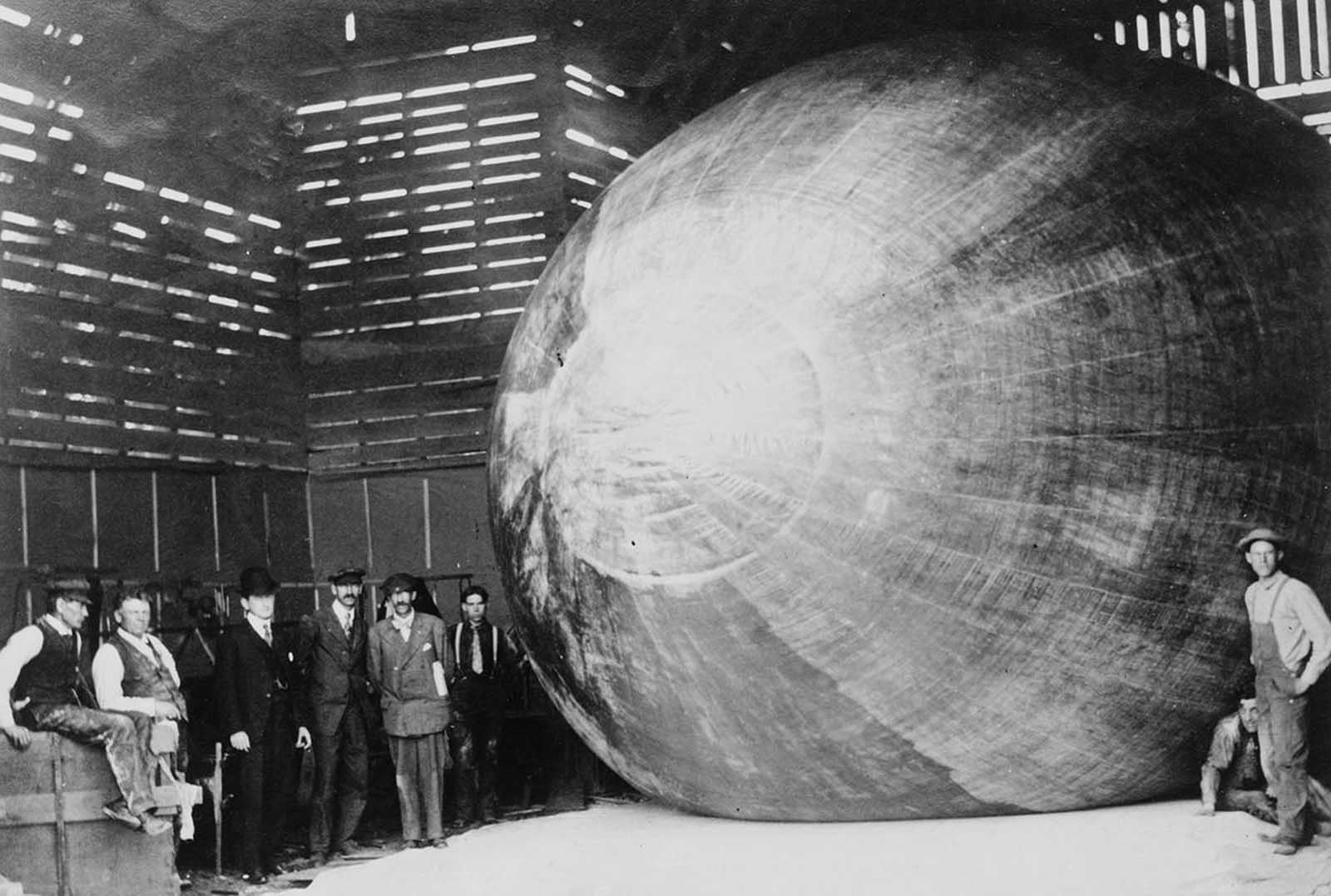

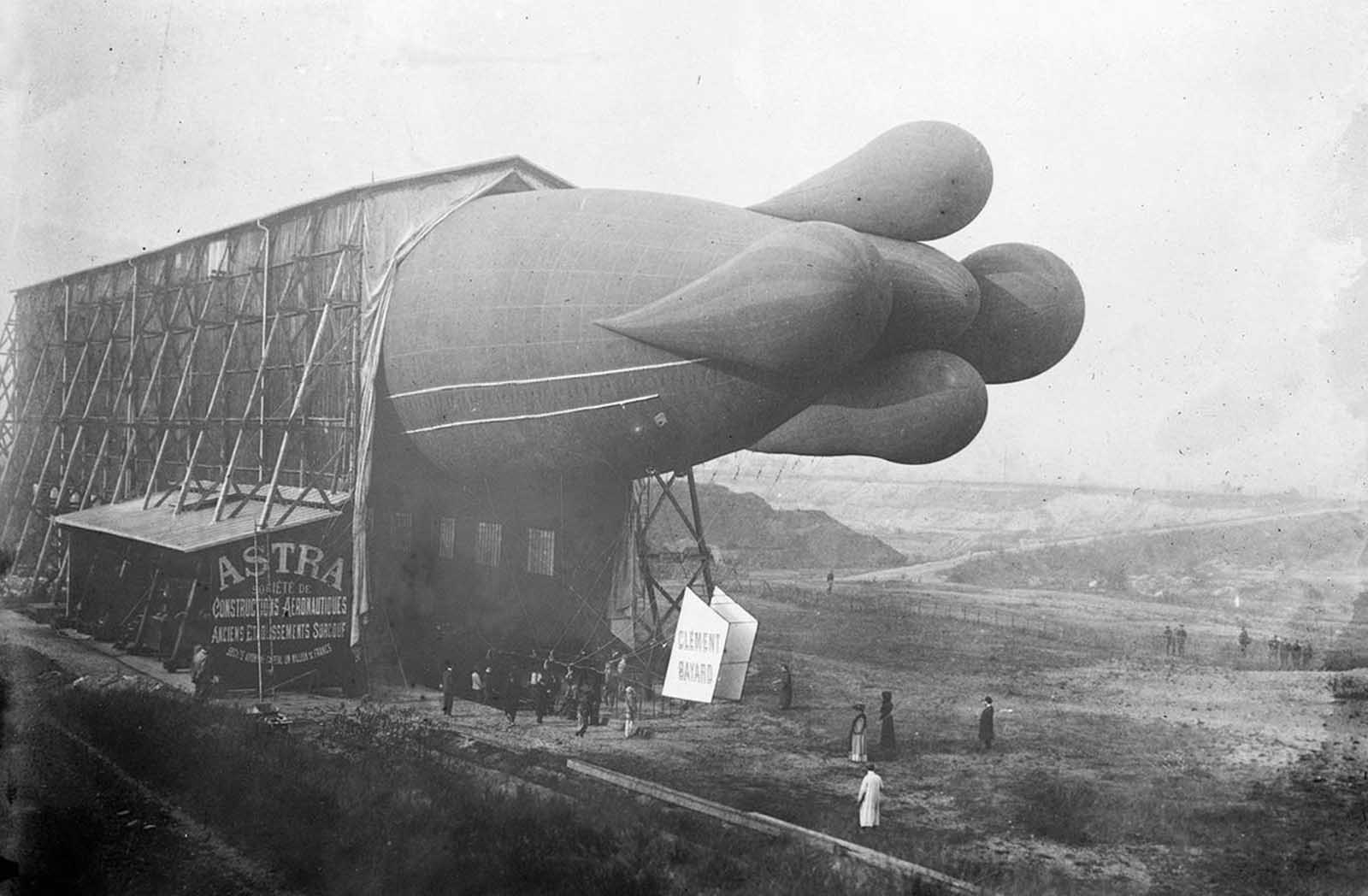

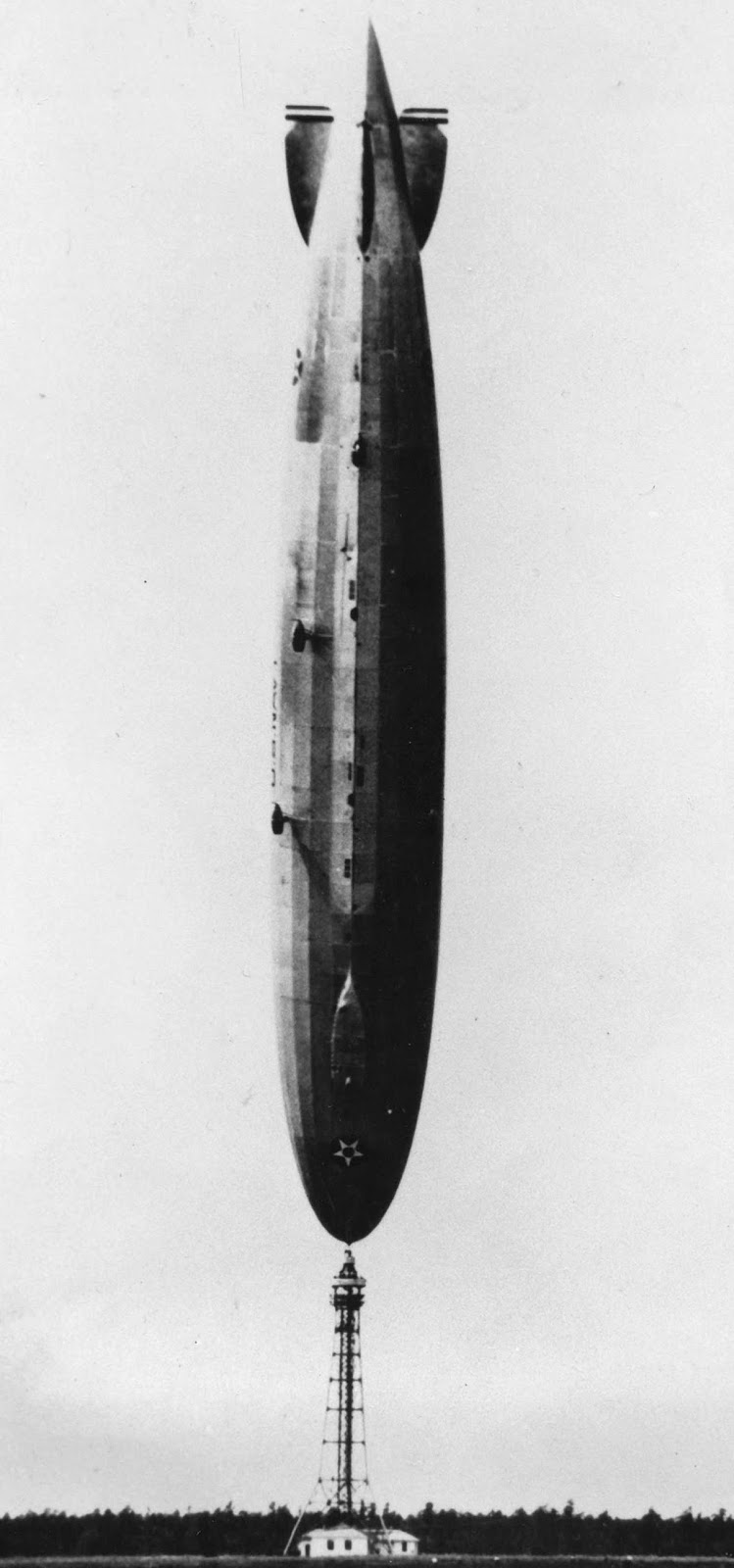

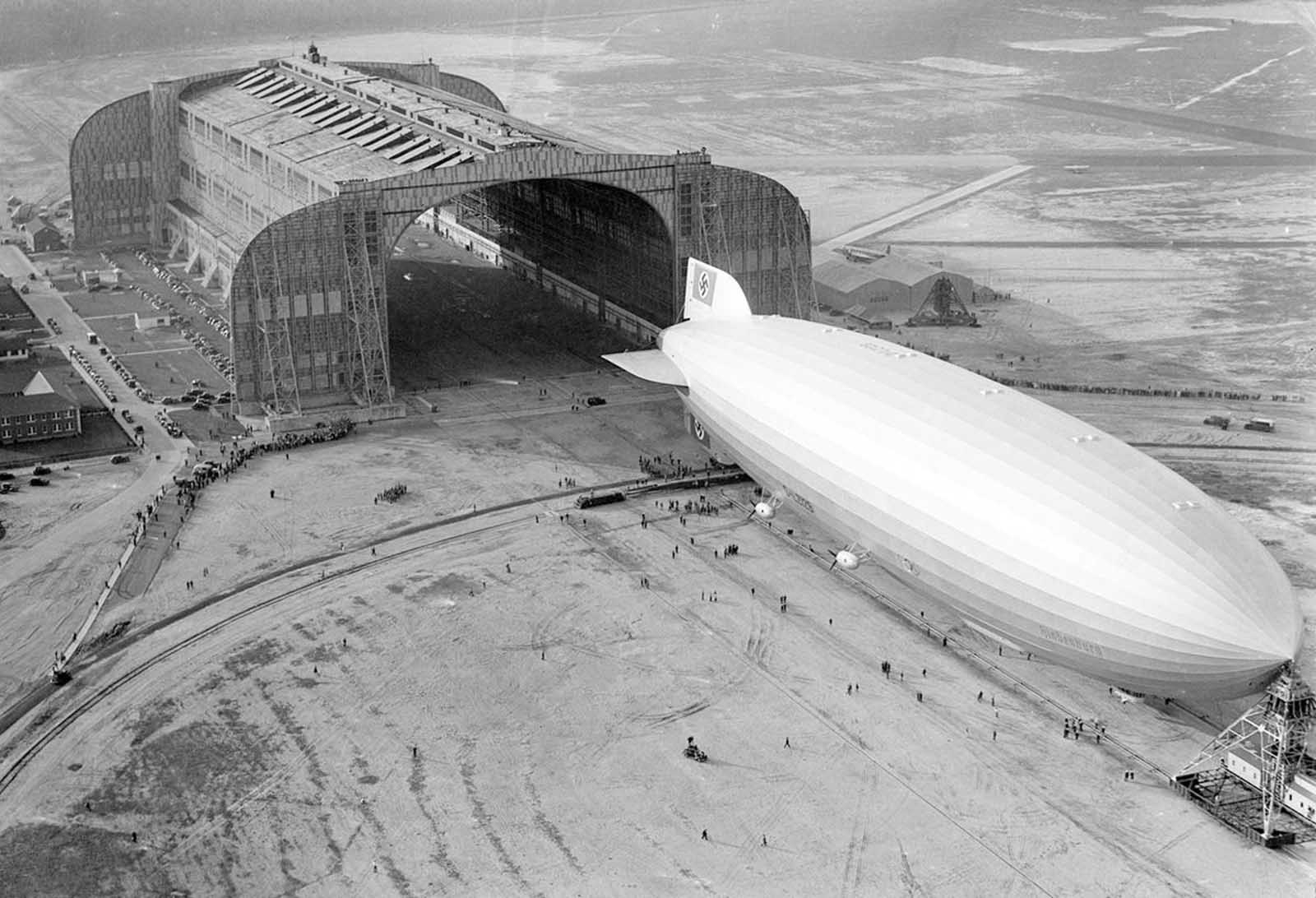

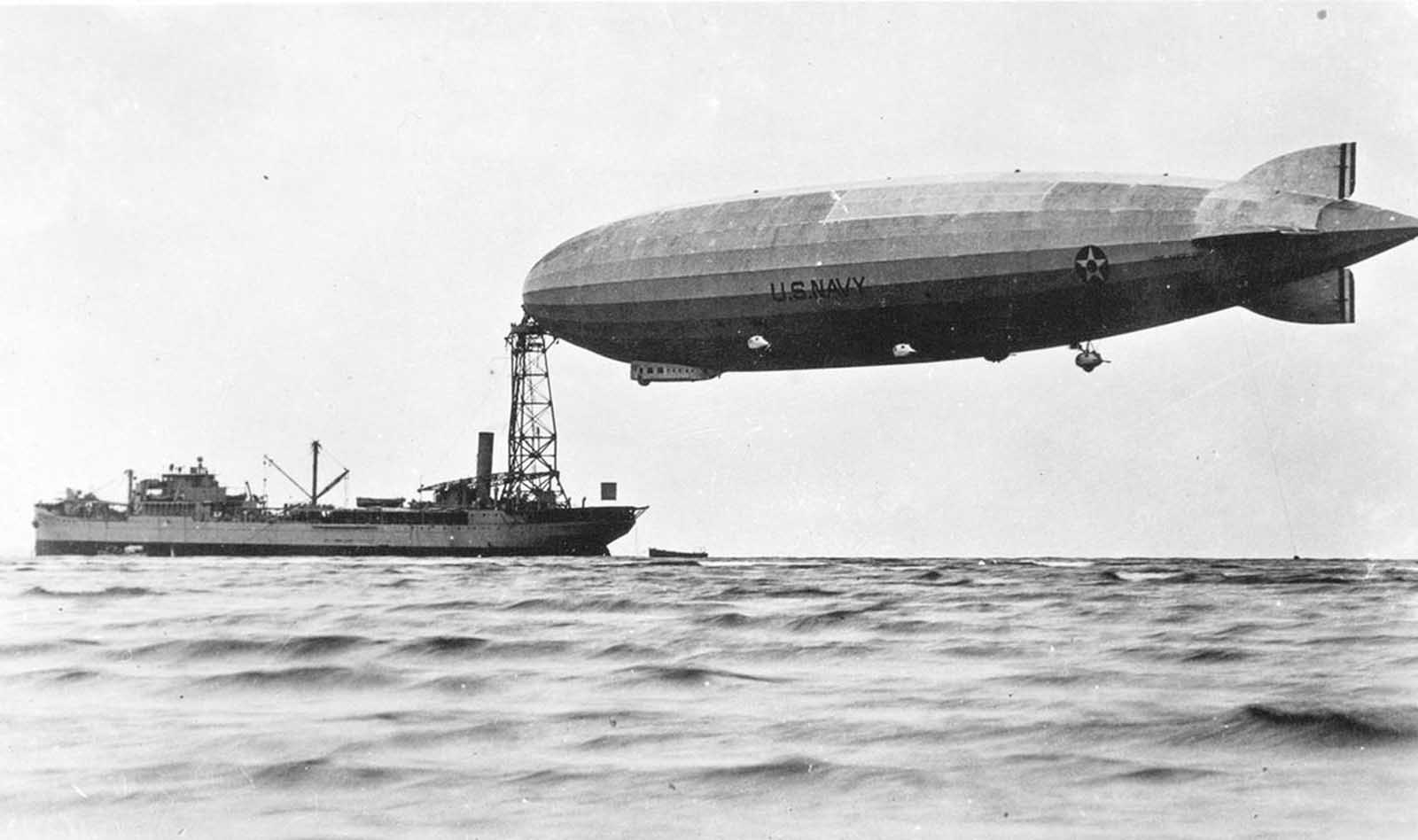

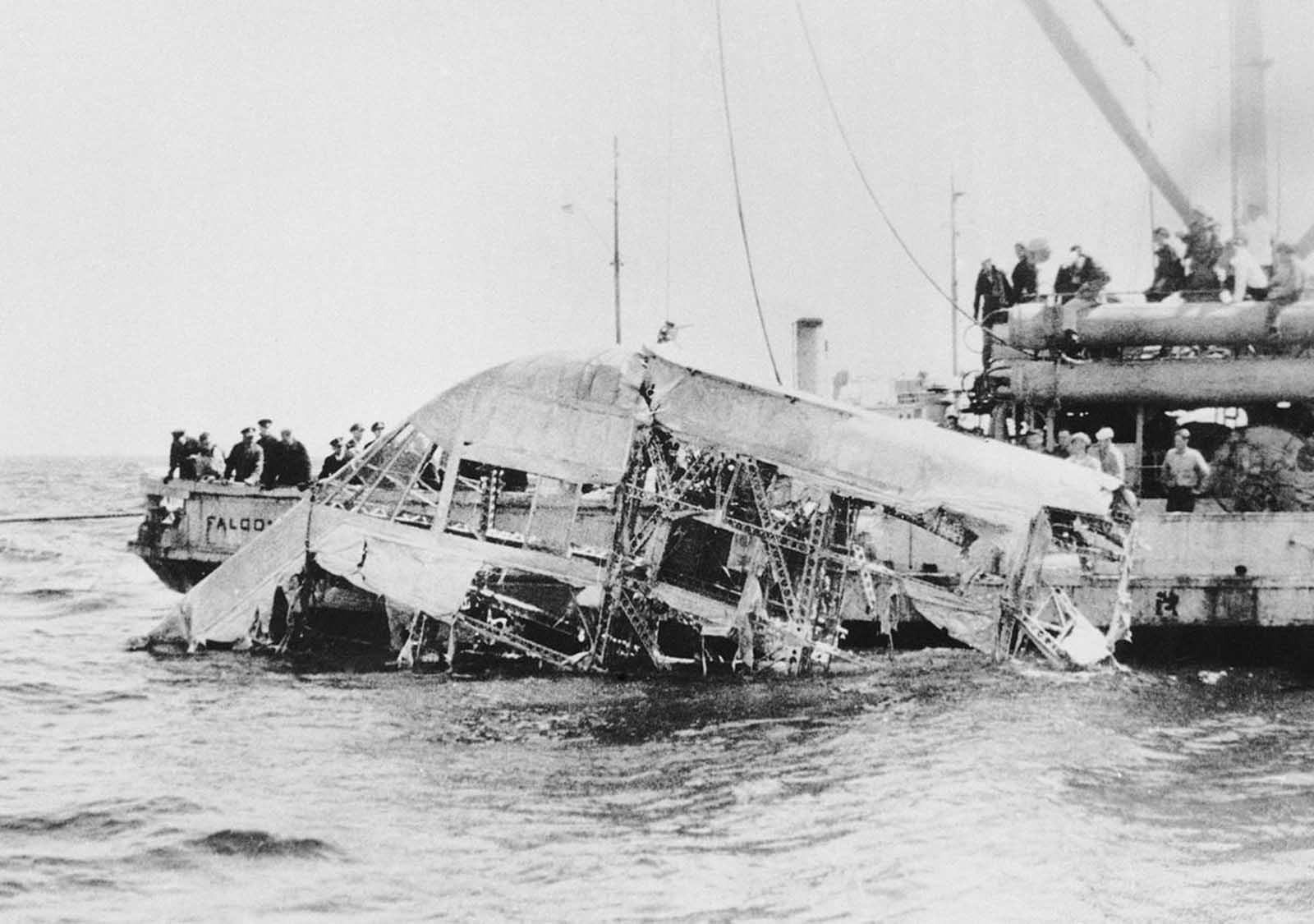

In 1784, he designed an airship that had an elongated envelope, propellers, and a rudder, unlike today’s blimp. Although he documented his idea with extensive drawings, Meusnier’s airship was never built. In 1852, another Frenchman, an engineer named Henri Giffard, built the first practical airship. Filled with hydrogen gas, it was driven by a 3 hp steam engine weighing 350 lb (160 kg), and it flew at 6 mi/hr (9 km/hr). Even though Giffard’s airship did achieve liftoff, it could not be completely controlled. The first successfully navigated airship, La France, was built in 1884 by two more Frenchman, Renard and Krebs. Propelled by a 9 hp electrically-driven airscrew, La France was under its pilots’ complete control. It flew at 15 mi/hr (24 km/hr). In 1895, the first distinctly rigid airship was built by German David Schwarz. His design led to the successful development of the zeppelin, a rigid airship built by Count zeppelin. The zeppelin utilized two 15 hp engines and flew at a speed of 25 mi/hr (42 km/hr). Their development and the subsequent manufacture of 20 such vessels gave Germany an initial military advantage at the start of World War I. It was Germany’s successful use of the zeppelin for military reconnaissance missions that spurred the British Royal Navy to create its own airships. Rather than duplicating the design of the German rigid airship, the British manufactured several small non-rigid balloons. These airships were used to successfully detect German submarines and were classified as “British Class B” airships. It is quite possible this is where the term blimp originates—”Class B” plus limp or non-rigid. During the 1920s and 1930s, Britain, Germany, and the United States focused on developing large, rigid, passenger-carrying airships. Unlike Britain and Germany, the United States primarily used helium to give their airships lift. Found in small quantities in natural gas deposits in the United States, helium is quite expensive to make; however, it is not flammable like hydrogen. Because of the cost involved in its manufacture, the United States banned the exportation of helium to other countries, forcing Germany and Britain to rely on the more volatile hydrogen gas. Many of the large passenger-carrying airships using hydrogen instead of helium met with disaster, and because of such large losses of life, the heyday of the large passenger-carrying airship came to an abrupt end. (Photo credit: Library of Congress / U.S. Navy / AP). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe