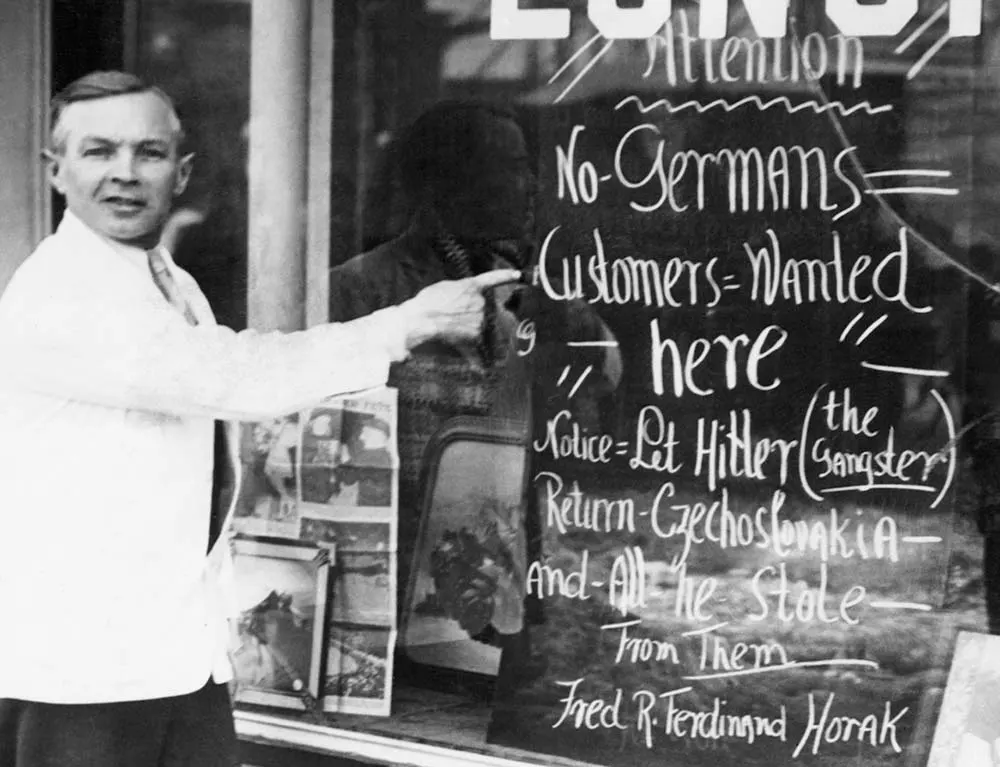

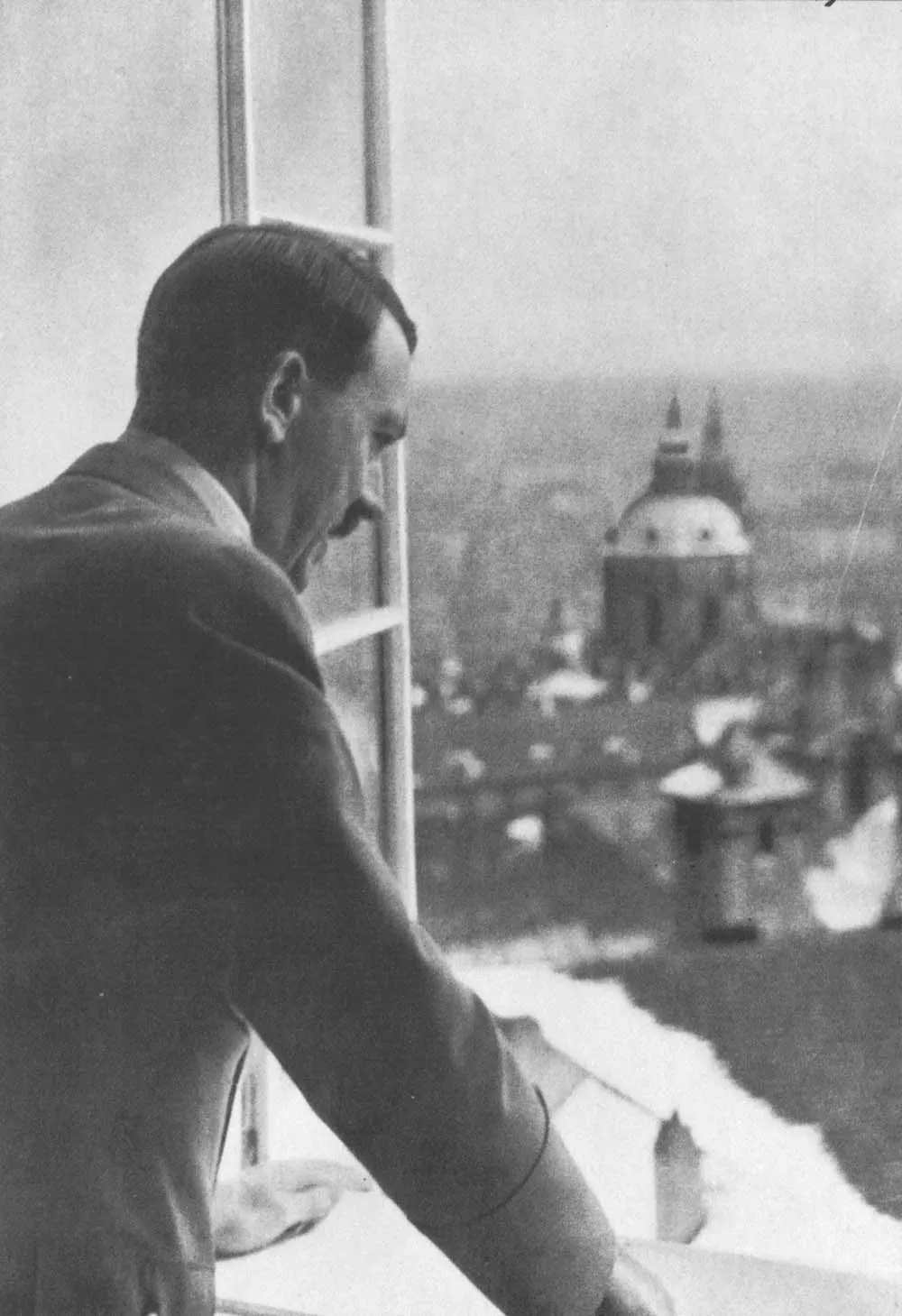

Czechoslovakia had signed treaties with France in 1926 and with the Soviet Union in 1935 precisely to protect itself against German aggression – the Soviet Union promised to intervene, but only if France acted first – but it remained exposed and vulnerable. Concurrent agreements among the Little Entente of Czechoslovakia, Romain, and Yugoslavia to defend against any aggression on the part of Hungary were of little use. Within the Czechoslovak Republic, a virulently German nationalist movement, led by Konrad Henlein and fully supported by the National Socialists in Berlin, resisted Prague rule and demanded that the Sudetenland, where most of Czechoslovakian Germans lived, be united with the Reich. When only two months after the Nazis’ annexation of Austria, German troops readied to march across the border in May 1938, the Czechoslovaks partly mobilized, and the situation became increasingly ominous. The ambassadors of France and Great Britain delivered a note to President Edvard Beneš on September 19 demanding that the republic hand over its Sudeten territories to Germany in exchange for a guarantee of its new borders, this to prevent an immediate occupation by the Wehrmacht, and suddenly the Czechoslovak Republic and its (few) friends were isolated. On September 23, in a desperate gesture, Czechoslovakia once more mobilized its army and air force. Hiter’s ally Benito Mussolini then proposed a four-power meeting to resolve the Czechoslovak crisis. The famous conference convened on September 29-30 (1938) in Munich with representatives of Germany, Great Britain, France, and Italy in attendance, Czechoslovaks being notably absent. Chamberlain, French Prime Minister Edouard Daladier, Hitler, and Mussolini signed an agreement that conceded to all of Germany’s demands. The Sudetenland was to be united with the Reich as of October 1; this and further concessions deprived the Czechoslovak Republic of a major part of its historical territory, its principal fortifications against Germany, and much of its iron, steel, and textile factories. Moreover with the loss of the Sudetenland came the threat of further losses of border territories in the east, which Poland and Hungary coveted. A week after mobilizing, Czechoslovakia capitulated on September 30. The incorporation of the Sudetenland into Germany that began on 1 October 1938 left the rest of Czechoslovakia weak. Moreover, a small northeastern part of the borderland region known as Zaolzie was occupied and annexed to Poland ostensibly to “protect” the local ethnic Polish community and as a result of previous territorial claims (Czech-Polish disputes in the years of 1918–20). Furthermore, by the First Vienna Award, Hungary received the southern territories of Slovakia and Carpathian Ruthenia, which was largely inhabited by Hungarians. As the Slovak State was proclaimed on 14 March 1939, the next day Hungary occupied and annexed the remainder of Carpathian Ruthenia. After fearing a Hungarian invasion, the Czech Prime Minister asked the German Wehrmacht to protect the remainder of the Czech lands. On the morning of 15 March, German troops entered the remaining Czech parts of Czechoslovakia (Rest-Tschechei in German), meeting practically no resistance (the only instance of organized resistance took place in Místek where an infantry company commanded by Karel Pavlík fought invading German troops). The Hungarian invasion of Carpatho-Ukraine encountered resistance but the Hungarian army quickly crushed it. On 16 March, Hitler went to Czech lands and from Prague Castle proclaimed the German protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. Besides violating his promises at Munich, the annexation of the rest of Czechoslovakia was, unlike Hitler’s previous actions, not described in Mein Kampf. After having repeatedly stated that he was interested only in pan-Germanism, the unification of ethnic Germans into one Reich, Germany had now conquered seven million Czechs. Hitler’s proclamation creating the protectorate claimed that “Bohemia and Moravia have for thousands of years belonged to the Lebensraum of the German people”. British public opinion changed drastically after the invasion. Chamberlain realized that the Munich Agreement had meant nothing to Hitler. Chamberlain told the British public on 17 March during a speech in Birmingham that Hitler was attempting “to dominate the world by force”. There are sources that highlighted the more favorable treatment of the Czechs during the German occupation in comparison to the treatment of the Poles and the Ukrainians. This is attributed to the view within the Nazi hierarchy that a large swath of the populace was “capable of Aryanization,” hence, the Czechs were not subjected to a similar degree of random and organized acts of brutality that their Polish counterparts experienced. Such capacity for Aryanization was supported by the position that part of the Czech population had German ancestry. Aside from the inconsistency of animosity towards Slavs, there is also the claim that the forceful but restrained policy in Czechoslovakia was partly driven by the need to keep the population nourished and complacent so that it can carry out the vital work of arms production in the factories. By 1939, the country was already serving as a major hub of military production for Germany, manufacturing aircraft, tanks, artillery, and other armaments. In March 1944, during Operation Margarethe Hungary was occupied by Germany, while beginning at the end of August 1944 with the Slovak National Uprising, Slovakia shared the same fate. The occupation ended with the surrender of Germany following World War II. During the German occupation between 294,000 to 320,000 citizens (including Jews, making up most of the casualties) were murdered. (Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / Bundesarchiv / Polish National Archives / Captions by James Bjorkman / Hitler and Czechoslovakia in World War II: Domination and Retaliation / Prague in Danger: The Years of German Occupation, 1939-45). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe