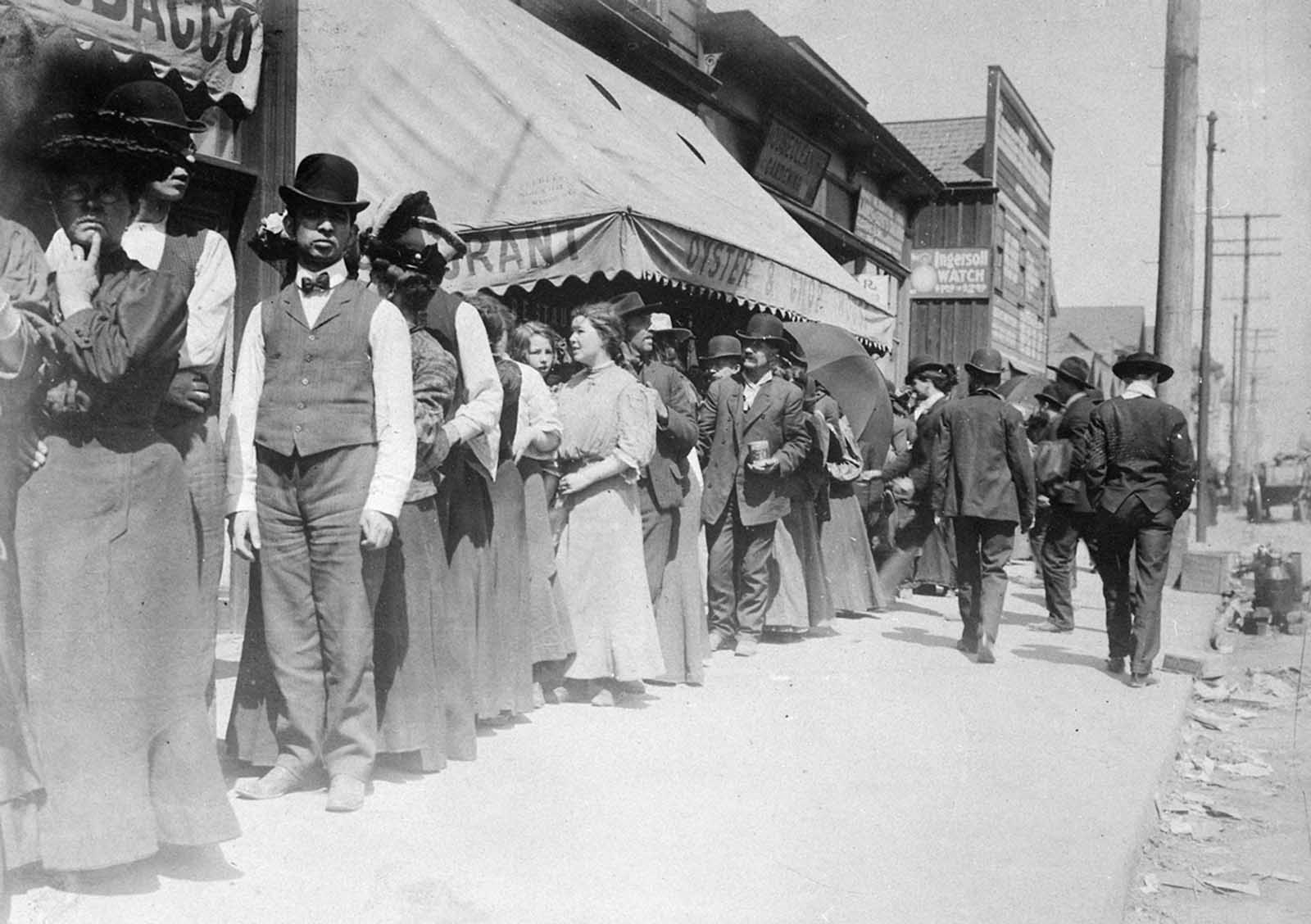

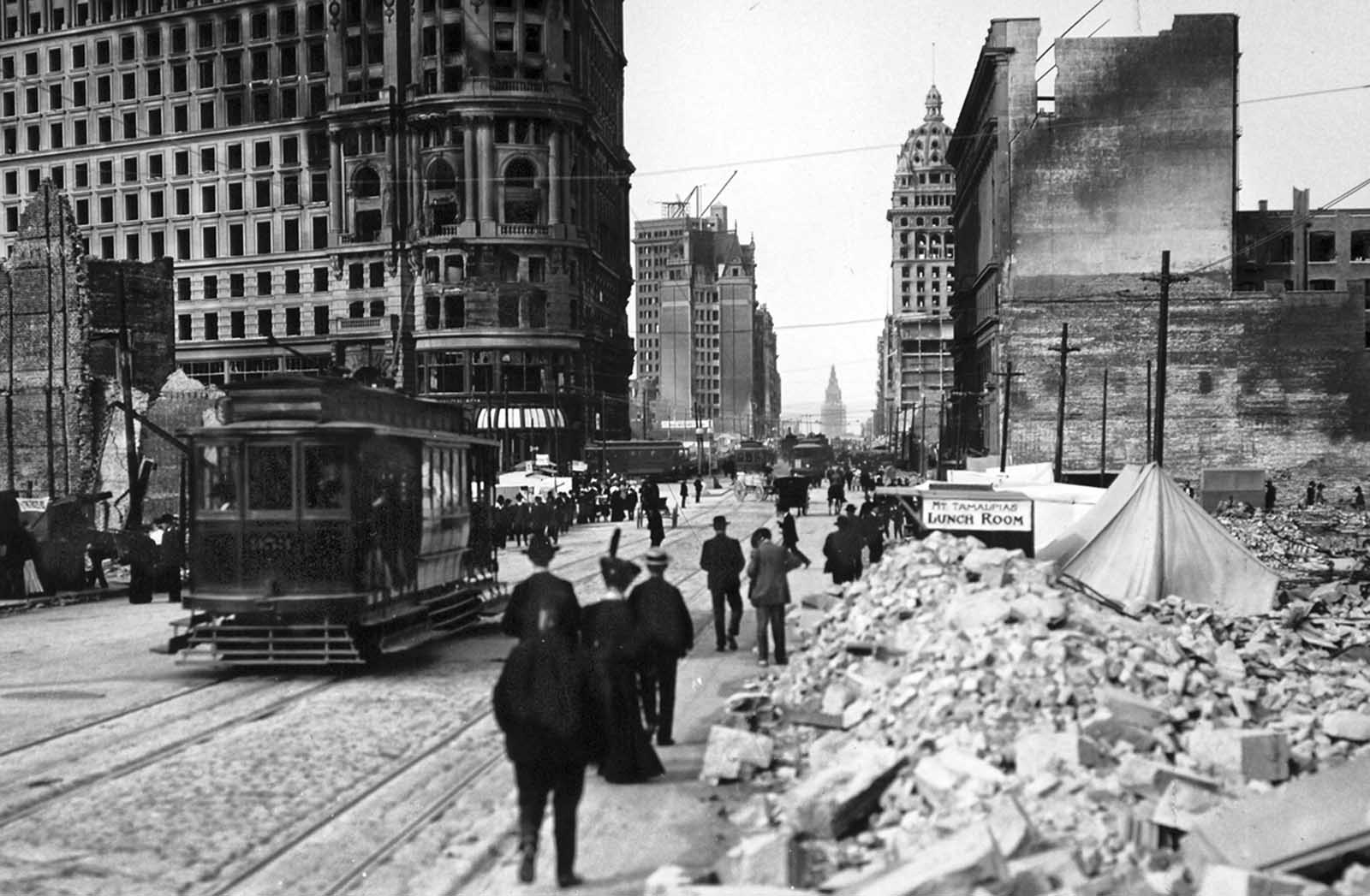

San Francisco’s very existence was the triumph of imagination over reality. In 1846 the site was largely barren sand dunes fringed with wind-stunted oaks and populated mainly by billions of fleas that tormented man and beast alike. In 1846 the scraggly little village of Yerba Buena, named after a local shrub, was clustered near the lip of Yerba Buena Cove in San Francisco Bay. It would be transformed by the discovery of gold in 1848. The Gold Rush helped Yerba Buena, now called San Francisco, vault from sleepy hamlet to ‘instant city.’ Thousands of gold seekers from every corner of the globe poured into California, boosting the city’s population from around 500 in 1847 to 30,000 in 1851. This intense growth continued throughout the 19th century. In 1906 Market Street was San Francisco’s main artery, a 120-foot-wide thoroughfare that showcased some of the city’s most impressive landmarks. Americans couldn’t help but be awed by what had been accomplished in a mere 60 years. The Union Ferry Depot, simply called ‘Ferry Building’ by most locals, anchored the eastern end of Market. Since San Francisco was on the tip of a peninsula, Ferry Building was one of the city’s major gateways. Its clock tower, which was inspired by the Giralda Bell Tower in Seville, Spain, spiked the sky above the waterfront like an exclamation point. The Palace Hotel was another jewel in the Market Street crown, the largest and most luxurious hostelry on the West Coast. Opened in 1875, it boasted 800 well-appointed rooms and rose an impressive seven stories high. It was the interior that awed most visitors, featuring a central grand court surrounded by tier after tier of columned galleries and crowned by a domed ceiling of amber-colored glass. The hotel was the brainchild of William Ralston, one of San Francisco’s earliest boosters. Equal parts hardheaded businessman, robber baron and dreamer, Ralston knew the area was vulnerable to earthquakes. In 1865 and 1868 the Bay Area had been shaken by temblors, and Ralston was determined to protect his creation from the capricious forces of nature. Three thousand tons of ‘earthquake proof’ iron banding strengthened the 2-foot-thick walls. Ralston also knew that fire was a danger, so he left nothing to chance. There was a 358,000-gallon subbasement reservoir beneath the grand court, and also six water tanks on the hotel’s iron roof. Hoses were stored on each floor to allow bellboys to fight any blaze. As a final touch, no less than 12 fire hydrants just outside the hotel on Market and New Montgomery streets were linked to the roof tanks. Passing the 18-story Call/Spreckels Building at Third and Market, a visitor would soon find himself at a triangle of land bounded by Market, Larkin and McAllister streets. This was the civic center, whose centerpiece was San Francisco’s new City Hall. The building was contracted by the city in 1871, but ‘cost overruns’ — seasoned with corruption on a massive scale — delayed its completion for decades. During that period, the partially finished building, its exposed steel girders looking like a forlorn skeleton, was soon dubbed ‘The New City Hall Ruin.’ It was finally completed and fully occupied by 1900. Turn-of-the-century San Francisco was a cosmopolitan city with one of the most ethnically diverse populations in the country. Only a few blocks north of Market Street was Chinatown, a district widely known as the largest Chinese community outside Asia. The official census of 1900 recorded some 11,000 Chinese living within Chinatown, but the real figure was probably 25,000 or more. Chinatown was both a thriving, self-sufficient community and a gilded ghetto, a bastion of Chinese culture and an expression of the white racism that forbade Asians to live anywhere else. To most whites, Chinatown was an exotic place of oriental mystery, where one could shop for Chinese trinkets, gawk at real or alleged opium dens, eat at a Chinese restaurant or simply stroll the streets taking in the colorful shops and temples festooned with Chinese characters and bulbous lanterns. But Chinatown was also an artificial creation, and any Asian who ventured out beyond its borders risked a severe beating — or worse — by ever vigilant white street thugs. Forbidden by racist laws to become naturalized citizens, most Chinese didn’t have the solace of family life. Chinatown’s population included only 1,300 women, in large part due to restrictive immigration laws. San Francisco’s new maturity was manifested in the arts, where it ranked alongside Chicago or even New York. On April 17, 1906, the great Italian tenor Enrico Caruso opened in Carmen at the Grand Opera House on Mission Street. He was scheduled to sing in La Boheme the next day, Thursday, and Faust on the following Saturday. Carmen was a great success, and after the performance Caruso returned to his suite at the Palace Hotel a happy man. At 5:12 a.m., Wednesday, April 18, 1906, San Franciscans were rudely awakened by a sharp jolt that lasted about 45 seconds. This was a foreshock, an overture to a terrible symphony of destruction. About 10 or 12 seconds after the shaking subsided, the city was rocked by a far more powerful temblor that lasted some 45 to 60 seconds. The earthquakes had come from the San Andreas fault, a deep fissure in the earth’s crust that extends some 600 miles. In 1906 scientists could only speculate on why earthquakes occur, but now, thanks to the study of plate tectonics, we have a better idea of the forces that had been unleashed. The San Andreas fault is the boundary between the earth’s North American Plate to the east and the Pacific Plate to the west. The Pacific Plate is moving north, the North American is moving south, the rate of ‘creep’ being about 2 inches a year. Sometimes the plates lock, allowing no room for further movement. The earth, however, is a dynamic entity, and as the plates continue to shift, incredible strain is produced. An earthquake occurs when the strain finally reaches the breaking point, and the two plates lurch forward, often overlapping, releasing huge amounts of pent-up energy in the process. Techniques for measuring the intensity of quakes had not been invented by 1906, but modern estimates place the San Francisco earthquake at about 7.9 on the present Richter scale. The shaking was terrible, accompanied by a ‘freight train’ rumble that was forever etched into the memories of survivors. Buildings swayed crazily, their facades collapsed, draft horses galloped in blind terror and brick walls tumbled into the street, raising acrid clouds of choking dust. At the Palace Hotel, Caruso literally got a rude awakening. The famed tenor remembered: ‘Everything in the room was going round and round. The chandelier was trying to touch the ceiling, and the chairs were all chasing each other. Crash-crash-crash! It was a terrible scene.’ One of the first casualties was Fire Chief Engineer Dennis T. Sullivan, who was mortally wounded when a chimney from the California Theater smashed without warning into the fire station where he was living. The fire department, faced with the greatest crisis in its history, was effectively decapitated. Most of the city’s residents were still in bed when the quake struck, but a few policemen, delivery wagon teamsters and other early risers were witnesses to the initial impact. San Francisco Examiner reporter Fred Hewitt had just talked to two policemen when the shaking started. Fissures appeared as streets rose and fell and rose again in a rolling motion, the undulations making it seem as if the earth itself was, as Hewitt reported, ‘breathing.’ To the casual eye, the quake damage seemed arbitrary, the whim of capricious nature. Some buildings were virtually intact, while others were heavily damaged. Much depended on construction techniques, materials used and above all the makeup of the ground underneath. During the Gold Rush, parts of the bay had been filled in to create new real estate. This ‘made ground’ was essentially landfill, and had performed badly in previous major shakes. The made ground consisted of loose earth, old timbers, rocks and other debris, and when shaking occurred, this hodgepodge lacked cohesion. Very strong temblors transformed landfill into a soft, unstable ‘pudding,’ a process known to science as liquefaction. City Hall was particularly hard hit, reduced to a ruin as the Greco-Roman columns that ringed the dome fell away with much of the masonry facade in a matter of seconds. The building site had once been a marsh, the soft ground making any large building erected there vulnerable in a major earthquake. In this case, however, nature had been helped by the greed of city officials and contractors during the nearly 30-year span of the building’s construction. In order to save money and to pocket government funds, shoddy materials were deliberately used. Old newspapers and trash had been incorporated into the building materials. Even before the great quake, City Hall’s internal sewage had seeped into its basement, collecting in a stinking pool of filth. The stench of sewage was the perfect metaphor for the stench of corruption seeping from behind the city’s handsome facade. The densely populated South of Market area was also hit hard. It was largely a working-class district with small businesses, rooming houses and restaurants. Much of the site had been a marsh in the Gold Rush period. The four-story Valencia Hotel came to symbolize the entire South of Market disaster. Three stories had sunk into the marshy soil before the whole building collapsed on itself. Only the fourth story, its walls crazily askew, remained above ground. Heroic rescue efforts managed to save about a dozen victims, but nearly 30 perished in the hotel. Many probably drowned, because a nearby water main had flooded the already mushy soil. Since City Hall was a total loss, a temporary command post was set up at the Hall of Justice near Portsmouth Plaza. When the quake hit, Mayor Eugene Schmitz was at his home at 2849 Fillmore St., a short ride from the Hall of Justice, so he lost no time in reporting for duty. He had been under a cloud lately, accused of graft and taking bribes, and this disaster was a chance for political salvation. Schmitz was originally president of the local musicians’ union, but in city affairs he really played second fiddle to political boss Abraham Ruef. Ruef was a Republican Party organizer who saw greater opportunities for riches by switching to the newly formed Union Labor Party. A master manipulator, Ruef used Schmitz’s handsome looks and Irish Catholic-German roots to win votes. Although he was a charismatic speaker and charming family man, Schmitz was still considered a lightweight who did the bidding of his ‘puppet master,’ Ruef. Since the entire slate of Union Labor candidates had been elected in 1905, that party now controlled the entire board of supervisors, with predicable results. Ruef, himself no stranger to accepting ‘fees’ for political favors, characterized his rapacious supervisors as ‘the paint eaters,’ because they ‘were so greedy that they would eat the paint off a house.’ Crusading editor Fremont Older of the San Francisco Bulletin had begun printing a series of exposés on the corruption, and Schmitz was heavily implicated. The earthquake was a heaven-sent opportunity for Schmitz to prove his worth and confound his detractors. Seeing some looting on the way to the Hall of Justice, the mayor decided to take immediate action. He issued a proclamation declaring, ‘Federal Troops, the members of the Regular Police Force, and all Special Police Officers have been authorized to KILL any and all persons engaged in looting or…any other crime.’ In the meantime, large and small fires had broken out all over the city; some estimates suggest as many as 60 blazes. These fires had many causes, including broken chimneys, overturned stoves, crossed electric wires and shattered gas mains. But when hard-pressed firemen attached hoses to hydrants, they found to their horror that there was little or no water available. Most hydrants only produced a weak, sporadic trickle before running completely dry. The city’s major reservoirs, Crystal Springs and Pilarcitos, were miles away to the south in San Mateo County. All the conduits that transported water to San Francisco were either near, or actually crossed, the San Andreas fault. And even if the reservoirs and aqueducts had emerged unscathed, it would not have made much difference. There were more than 300 water main breaks within the city limits. The San Francisco Bay area was home to several military bases, including the historic Presidio and Mare Island. Brigadier General Frederick Funston was on hand when the temblors struck and found himself in command of the Department of California because his superior, General Adolphus Greeley, happened to be away in Washington, D.C. Funston, who stood 5 feet 4 inches tall and weighed a mere 120 pounds, was a pint-sized and pugnacious officer who was determined to save the city by any means possible. While Funston issued a flurry of orders to Army units, the Navy galvanized its own forces. Navy Lieutenant Frederick Newton Freeman, in temporary command of Preble, sailed the destroyer and two tugboats, Active and Leslie, to the stricken city. Freeman, who would emerge as one of the heroes of the tragedy, recognized that water was the key to San Francisco’s survival. There were a number of tugboats along the waterfront, and all performed heroic service under Freeman’s direction. The tugs pumped seawater from the bay, which was fed into hoses to fight the fires along the waterfront. Freeman also pumped 5,000 gallons of fresh water from tug Sotomoyo‘s tanks into the boilers of the fire engines desperately fighting the conflagration. And the lieutenant had the foresight to store 200 gallons in barrels for parched San Franciscans, who were ‘piteously crying for water.’ When the waterfront blazes were under control, Freeman offered assistance that helped save the area around Montgomery and Jackson streets, today’s Jackson Square. A hose snaked from the tug Leslie up and over Telegraph Hill, through Broadway to New Montgomery (now Columbus Avenue) and finally to the Jackson area. Freeman later commented that his men did their ‘best work’ here, Leslie‘s precious conduit of saltwater stretching over 11 city blocks. Because of Freeman and his men, a number of Gold Rush-era buildings, some of the oldest in San Francisco, survive to this day. Earlier, a few hours before Freeman arrived on the scene, Funston sent messages to the Presidio and Fort Mason ordering the troops there to report to San Francisco Police Chief Jeremiah Dinan at the Hall of Justice. The troops fanned out into the city, guarding vulnerable buildings, restoring order and preventing looting. In many cases, however, the soldiers did more harm than good by forcing thousands to evacuate their homes, ostensibly in the name of saving lives. But many of these people were able-bodied and more than willing to take an active part in saving their homes and businesses. The story of Dr. J.K. Plincz is a prime case in point. He was a young surgeon who lived in an octagonal house at 1027 Green St., and he and some neighbors — and a few others — decided to save their homes. Working with determination, they wet blankets, rugs and carpets with water that had been painstakingly collected and used them to smother small fires and extinguish sparks before they could spring to malevolent life. A soldier appeared and ordered Dr. Plincz to evacuate immediately. Orders were orders, and it seemed foolhardy to argue with an armed soldier. One wrong word and you might find yourself facing the business end of a bayonet-tipped Springfield rifle. But Plincz decided to take a different tack. He was friendly, talkative and plied the soldier with several glasses of good wine. The doughboy relented and allowed the Green Street defenders to stay. Five houses — including Dr. Plincz’s home — survived. Since the fire department had few means to combat the blazes, it was agreed that firebreaks would have to be created, by ruthlessly dynamiting buildings that were in the path of the growing conflagration. Fire department officials were in favor of the new and desperate tactic, and Funston insisted it was ‘the only way.’ Mayor Schmitz was not so sure, especially when the properties in question were owned by some of his supporters. In the end, Schmitz allowed himself to be persuaded, but orders were given to wait until the last possible moment before a building was blown. Unfortunately both civilian firefighters and soldiers had little or no experience with explosives, and their clumsy efforts actually spread the fire. Funston made an effort to consult with Schmitz, but at times he acted in a high-handed, arbitrary manner, virtually ignoring civilian authority. Martial law had not been declared, but the general issued orders as if he were on a campaign. He grew more convinced dynamiting was the city’s only salvation, even though it was clear by the second day that the strategy was deeply flawed. When dynamite stocks ran low, Funston became obsessed with finding more. He didn’t seem to know, or care, that the tugboats along the waterfront were helping combat the fire with their supplies of water. The general ordered that all such vessels be pulled out of the firefighting line and sent for more dynamite. In one instance, Funston ordered the tug Pricilla‘seized,’ placed under the command of 1st Lt. Raymond W. Briggs, and then sent it to Point Pinole to get more explosives. Lieutenant Freeman was obviously loath to criticize a superior officer, but he noted Pricilla was the ‘only tug available in my vicinity.’ His report also used the words’seize’ and’seized,’ the implication of force being a strong, if oblique, criticism of Funston. The fabled Palace Hotel, iconic symbol of the Bay City, survived the earthquake only to succumb to the fire. Guests like Caruso were shaken, windows were broken and some interiors were wrecked, but the building seemed to have remained structurally sound. Fears that the Palace would collapse and its floors ‘pancake’ happily proved false. Ironically, the fire department siphoned off all the Palace’s water resources to fight waterfront blazes, and when the flames attacked the building in earnest it was as helpless as its neighbors. The Call Building was also a fire victim. Steel frame buildings generally perform well in earthquakes, and the Call building was no exception. Unfortunately it too was gutted by the great fire. In Chinatown, one of the most densely populated sections of the whole city, casualties must have been high. Most Chinese were from Kwantung (Guangdong), so shouts and pleas for aid were in the Cantonese dialect. ‘Aeeya! dai loong jen!’ they screamed. ‘The earth dragon is wriggling!’ Frightened residents ran out of the damaged buildings, but Chinatown’s picturesque narrow streets and alleys were potential deathtraps from falling cornices and other debris. Hundreds of Chinese ran to the relative safety of Portsmouth Square, where they gathered in large groups. In some respects, the Chinese were even more vulnerable than other San Franciscans. Because of ‘heathen Chinee’ stereotypes and the prevailing racism of the time, they would get little help and less sympathy from hard-pressed city authorities. Traumatic memories of white persecution ran deep, and most Chinese were afraid of seeking food, medical attention or shelter from city aid stations. Soldiers evacuated Chinatown as they did other parts of the city, and the dynamiting began. Lieutenant Freeman, so heroic in other respects, shared the common prejudices of the time. Some Chinese remained behind and the naval officer noted that ‘at least 20 Chinese, opium fiends and drunks, were blown up by dynamite.’ Another report laconically mentioned that several mangled Chinese bodies could be seen in the ruins, and that ‘in at least one building 5 or 6 bodies were thrown 50 feet into the air and back into the flames.’ The fires coalesced into three major blazes — south of Market, north of Market and in the Hayes Valley, west of the shattered City Hall. Fanned by high winds, this malevolent trio soon united to become one raging firestorm. The inferno grew so intense that temperatures reached upward of 2,700 degrees Fahrenheit. Flames crackled and roared, producing a huge black column of smoke that some claimed rose five miles into the sky. The great city by the bay seemed to be doomed, immolated on its own funeral pyre. Van Ness Avenue, a broad thoroughfare that ran on a north-south axis, was a ‘natural’ firebreak and the city’s last major line of defense. There were still residential areas west of Van Ness that were relatively unscathed by the earthquake — but would they succumb to the fire? The great inferno jumped Van Ness in one or two places, but exhausted firefighters managed to hold the line. By Saturday, April 21, the fire had essentially burned itself out. Not long after, a drenching rain fell, too late to fight the fire but welcome nevertheless. In the coming months, relief and reconstruction were the top priorities. No fewer than 514 city blocks — four square miles — had been destroyed by fire. An estimated 28,000 buildings had been consumed in the great fire, and property damage losses ranged up to $500 million. City fathers, worried that future investors might be scared off, downplayed the number of casualties. Various figures were bandied about, but they had one thing in common — they were suspiciously low, at least given the magnitude of the disaster. One early estimate claimed 667 dead and 352 missing. Pioneering research by San Francisco City Librarian Gladys Hansen put the death toll at more than 3,000 people, while recent researchers suggest around 4,000. All generally agree that 250,000 people were rendered homeless. San Francisco government officials made an attempt to move Chinatown to Hunter’s Point, a remote location barely within the city limits. The plan was foiled, in part due to the building plans of local businessman Look Tin Eli. Eli was ABC — American-born Chinese — and he hired architects to make his rebuilt store more exotic and ‘Asian’ looking. The idea caught on, and pagoda roofs and other Chinese motifs helped make the restored Chinatown a major tourist attraction. Ironically, the disaster had an unexpected silver lining for the Chinese. The earthquake and fire completely destroyed city records, including birth certificates. The only way a Chinese person could be a citizen was to be born in the United States, so hundreds came forward after the quake to get new documentation, claiming their birth certificates had been consumed by the flames. Many were successful, though eventually the authorities caught on. If every citizenship claim had been true, each Chinese woman living in San Francisco’s Chinatown would have had to have given birth to 500 children! San Francisco has a history of surviving disasters. In the Gold Rush period, the city burned to the ground no less than six times between 1849 and 1851. The phoenix was adopted as its symbol, a mythical bird that arises reborn from its own ashes. San Francisco did rise again, and by 1915 it was hosting the Panama Pacific International Exhibition. San Francisco survived because of the courage, endurance and unfailing sense of humor of its citizens. Not long after the disaster, a sign appeared that poked fun at an East Bay rival and summed up the San Francisco spirit. ‘Eat, Drink, and Be Merry,’ the slogan read, ‘For Tomorrow We May Have to Go to Oakland.’ (Photo credit: Library of Congress / National Archives. Article by: Eric Niderost – originally published in the April 2006 issue of American History Magazine). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe