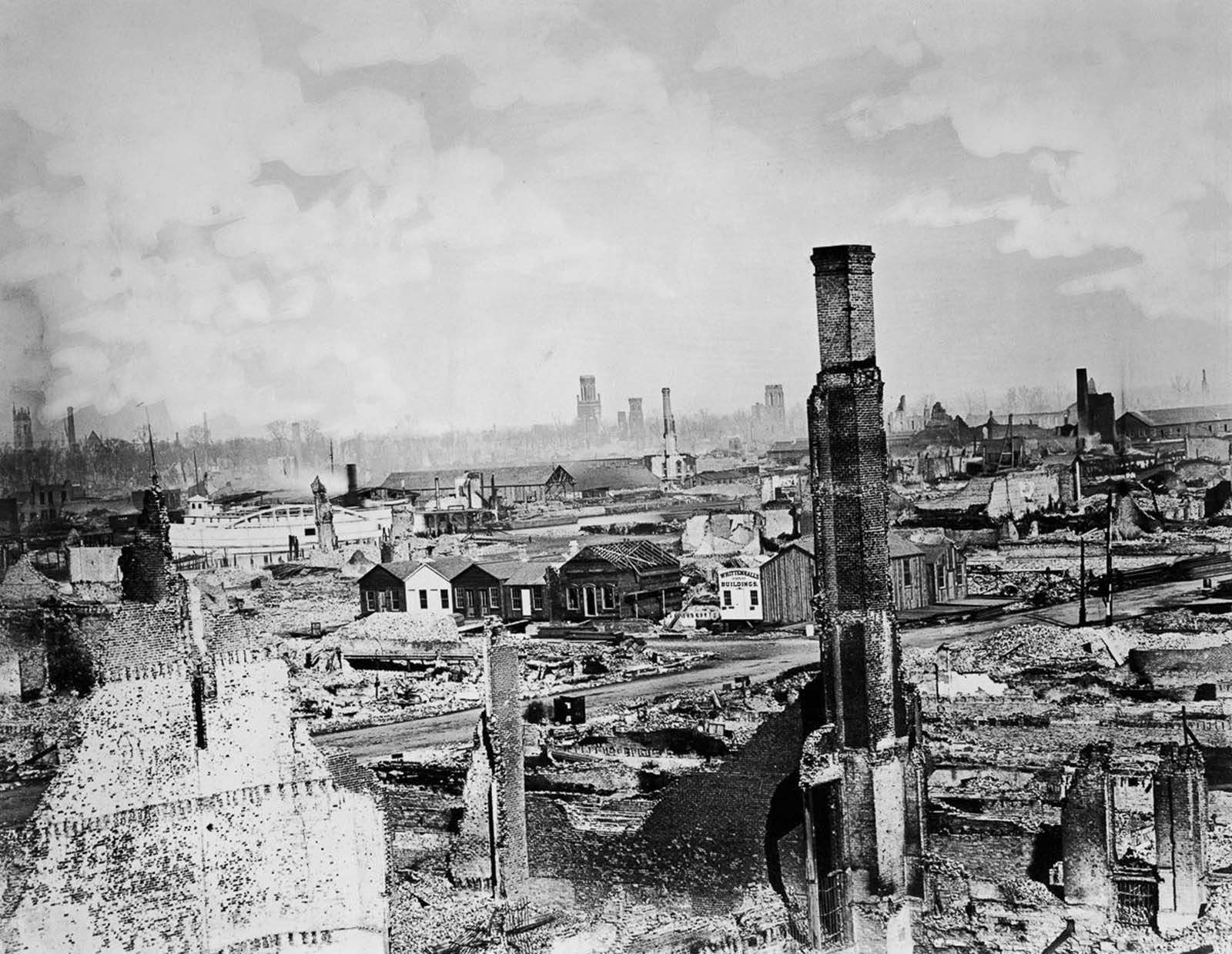

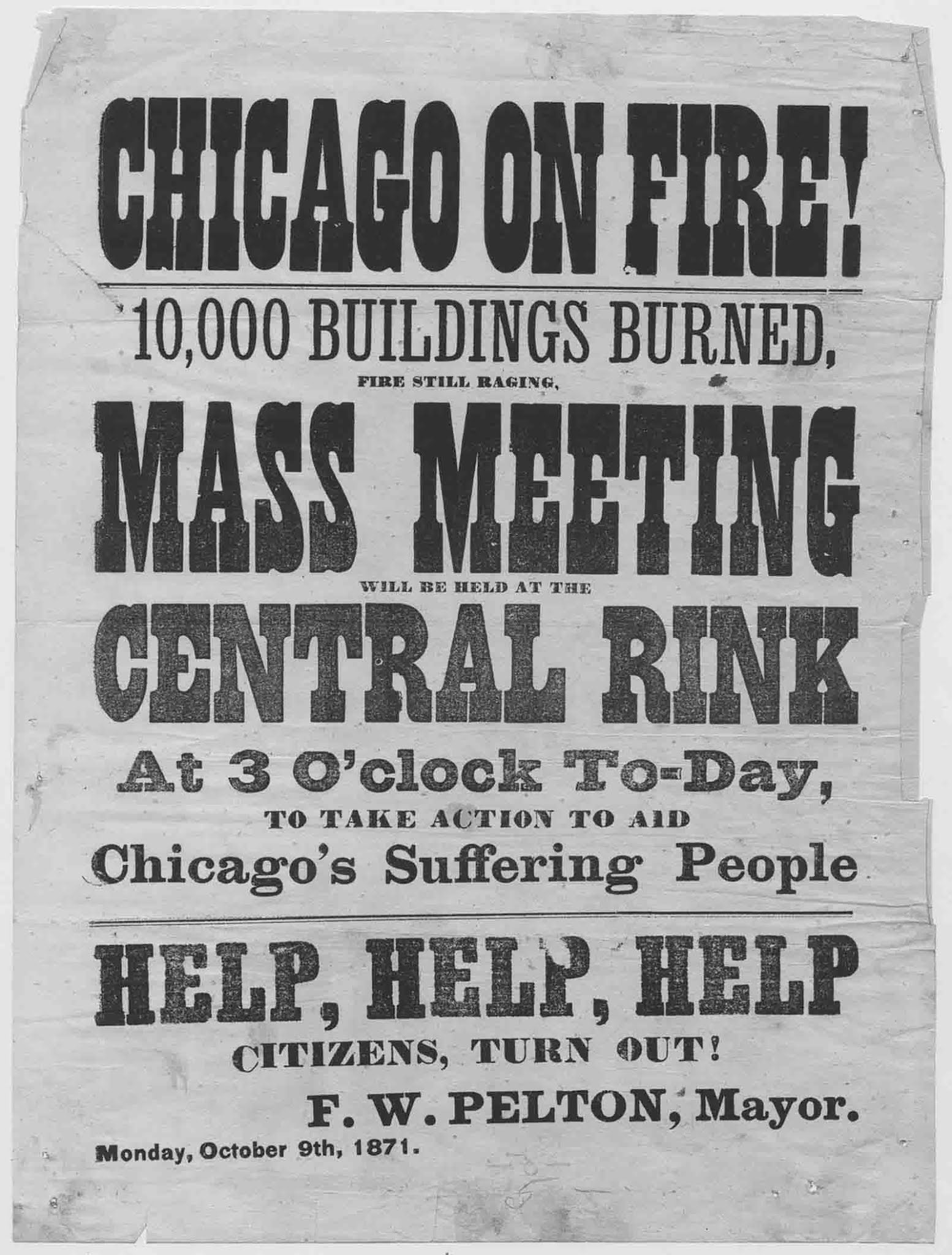

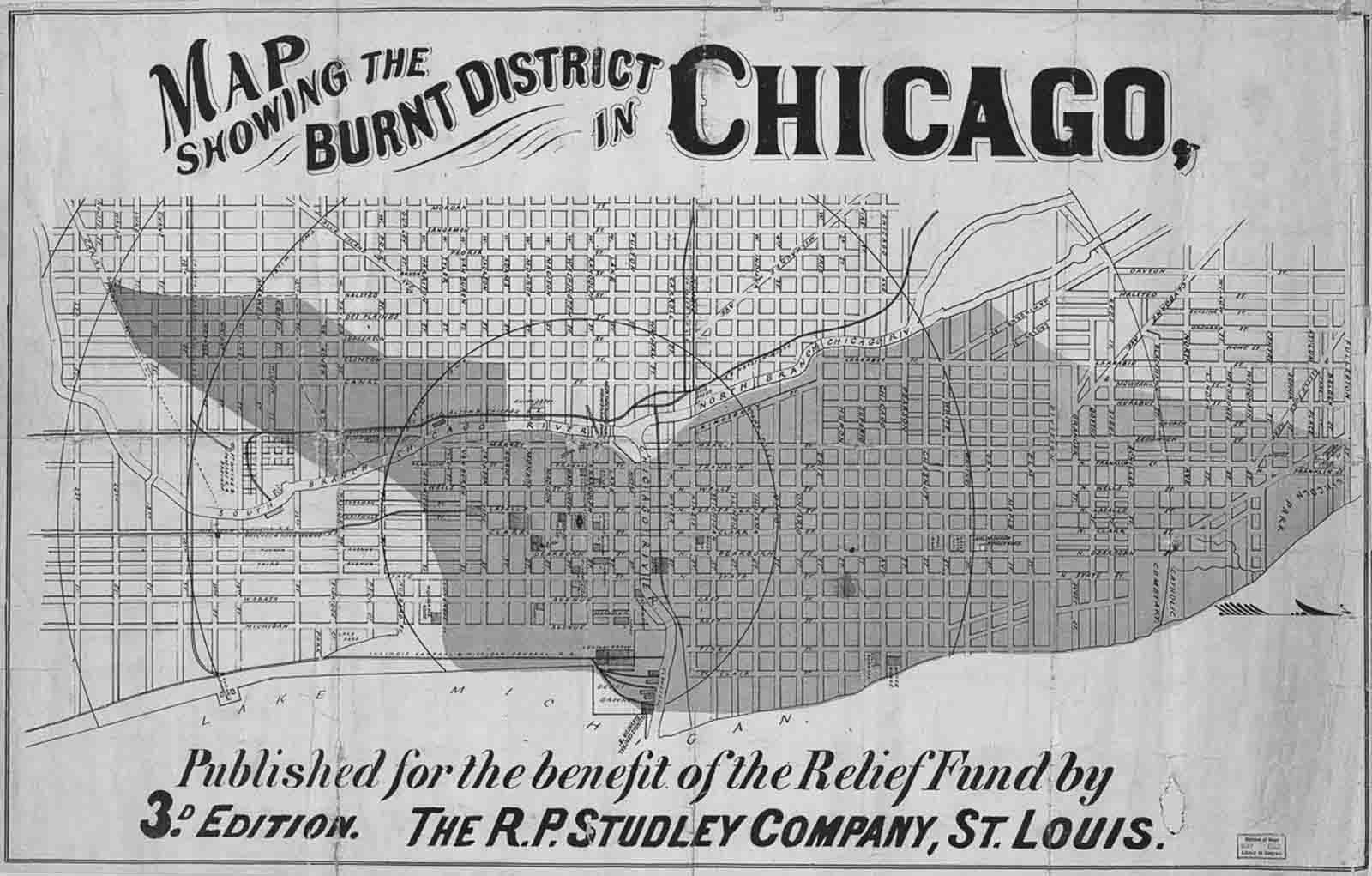

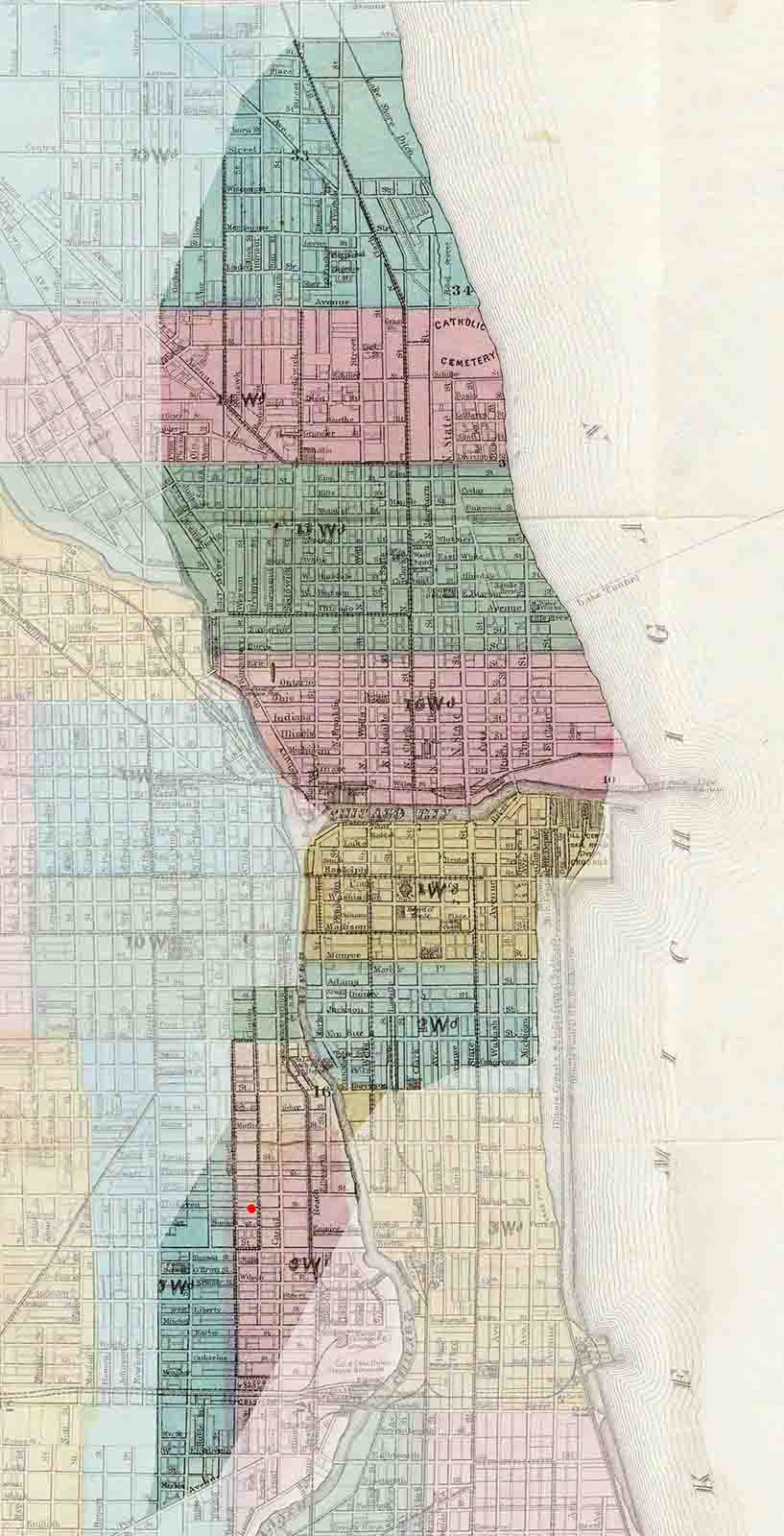

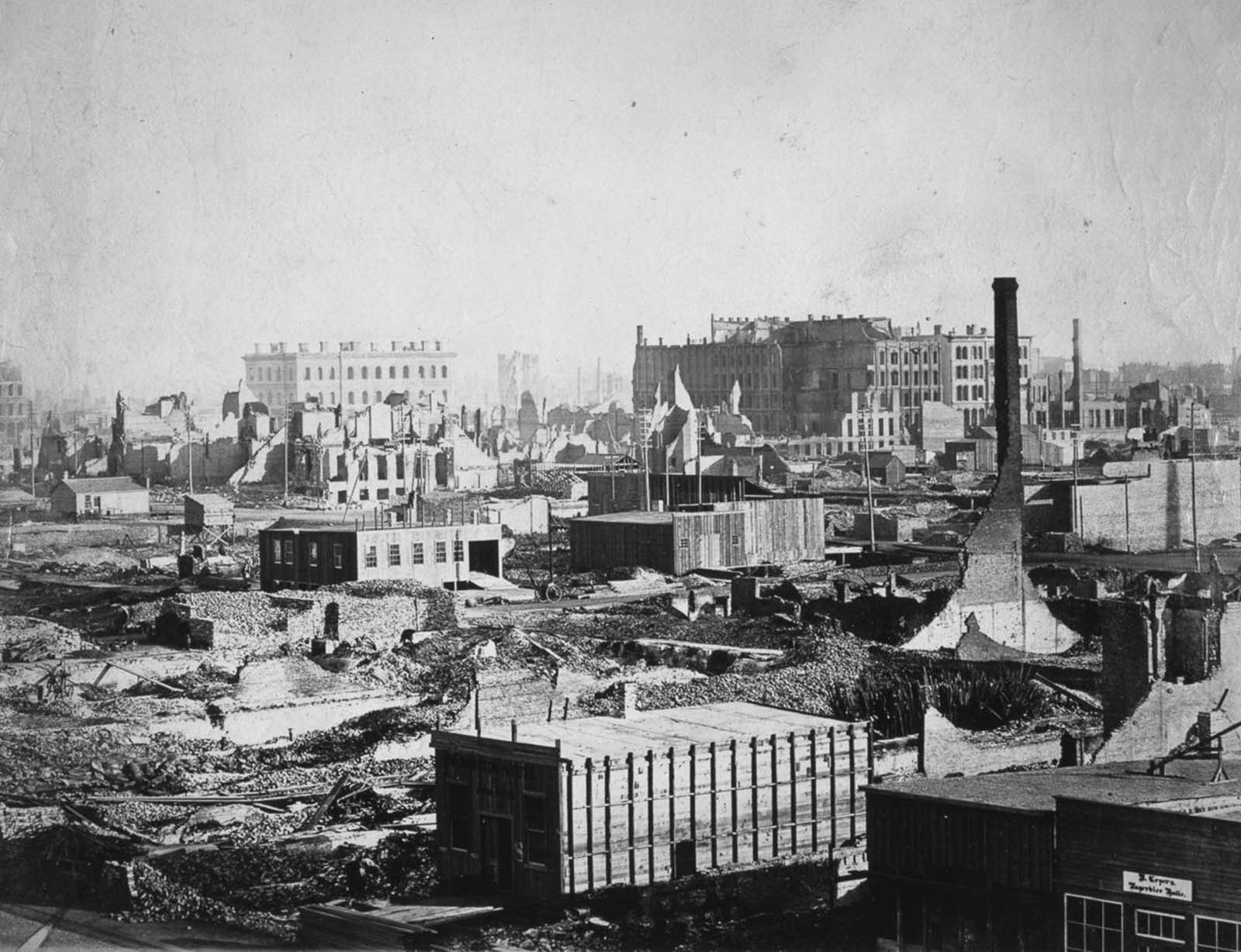

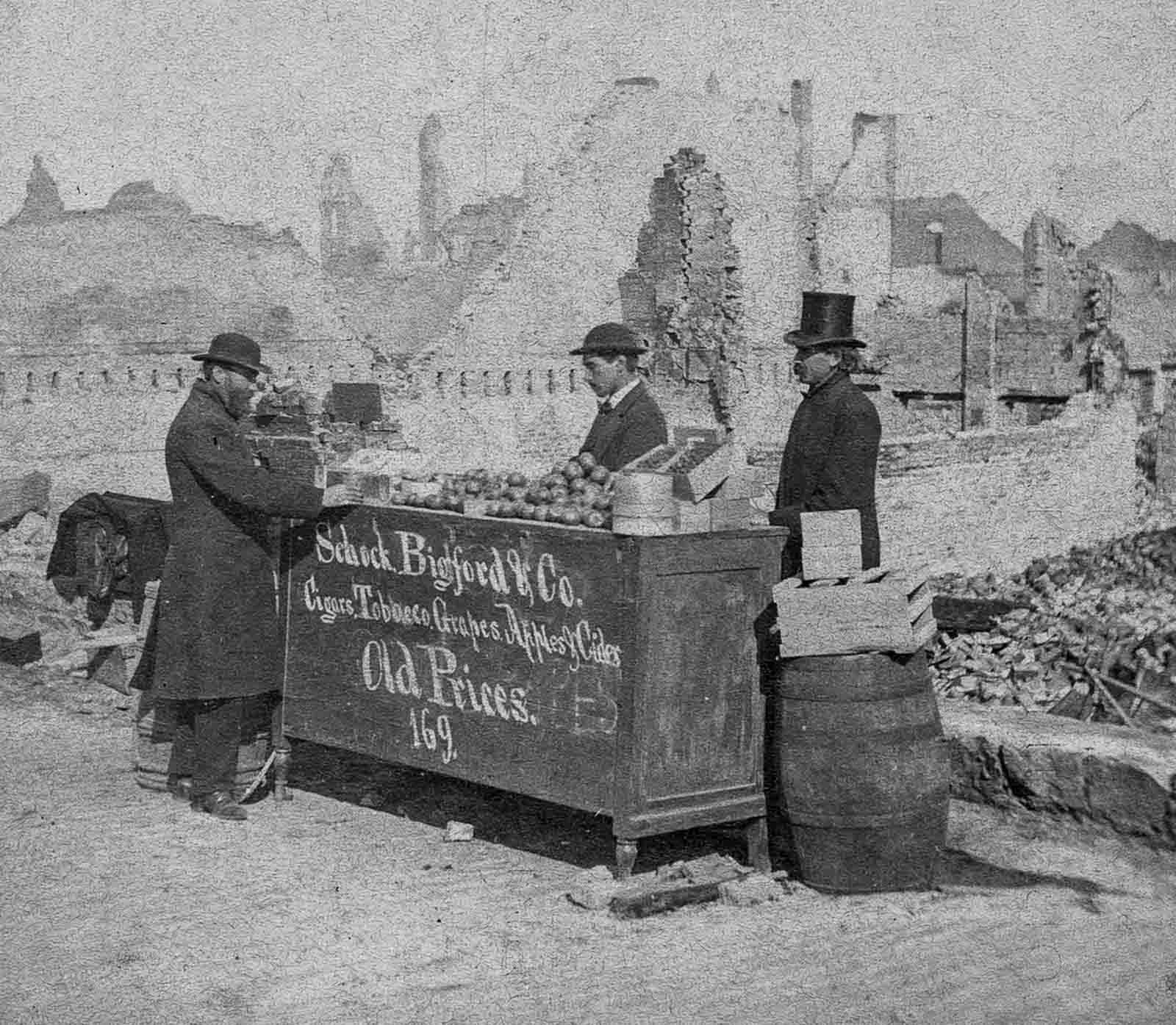

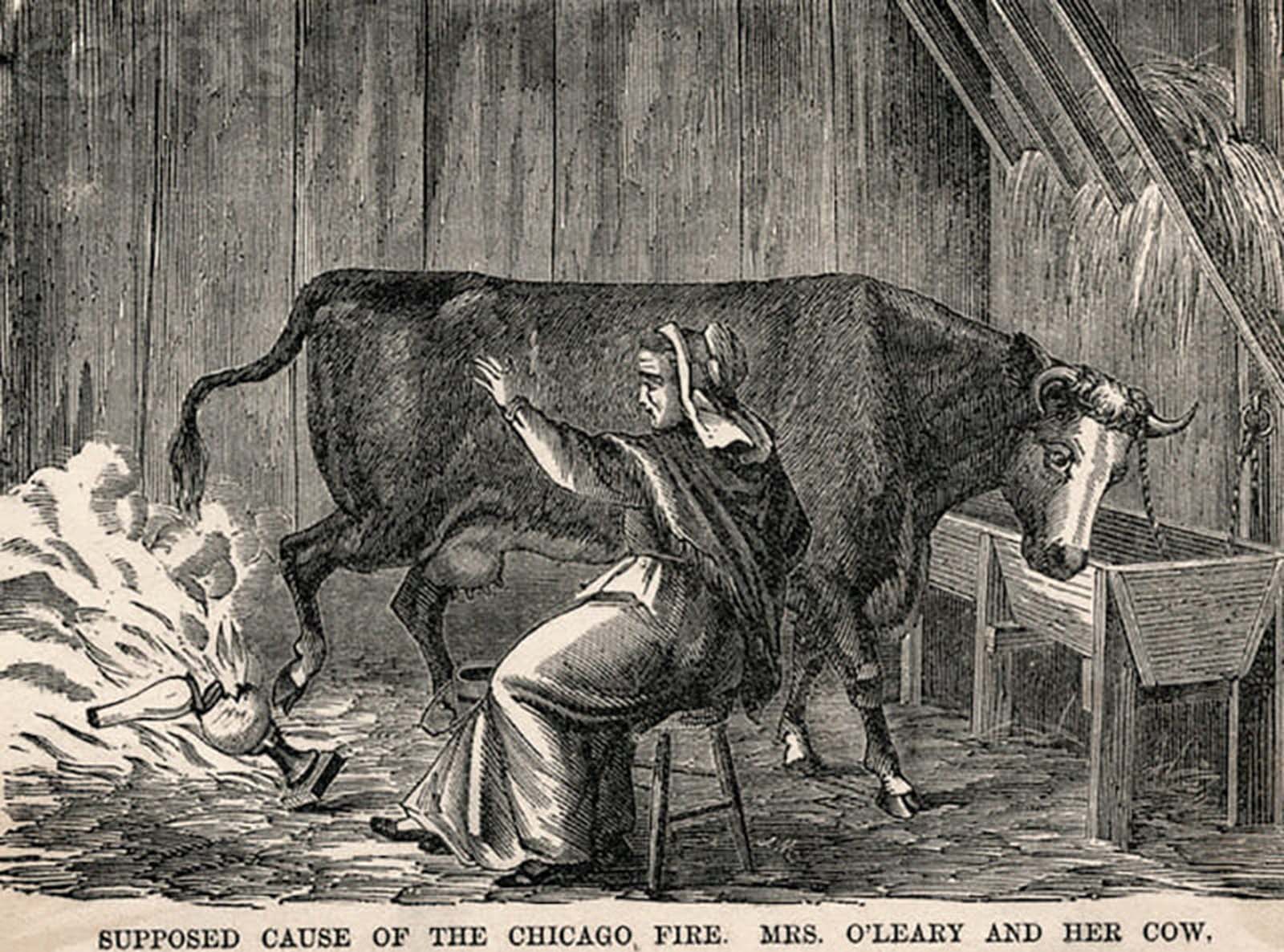

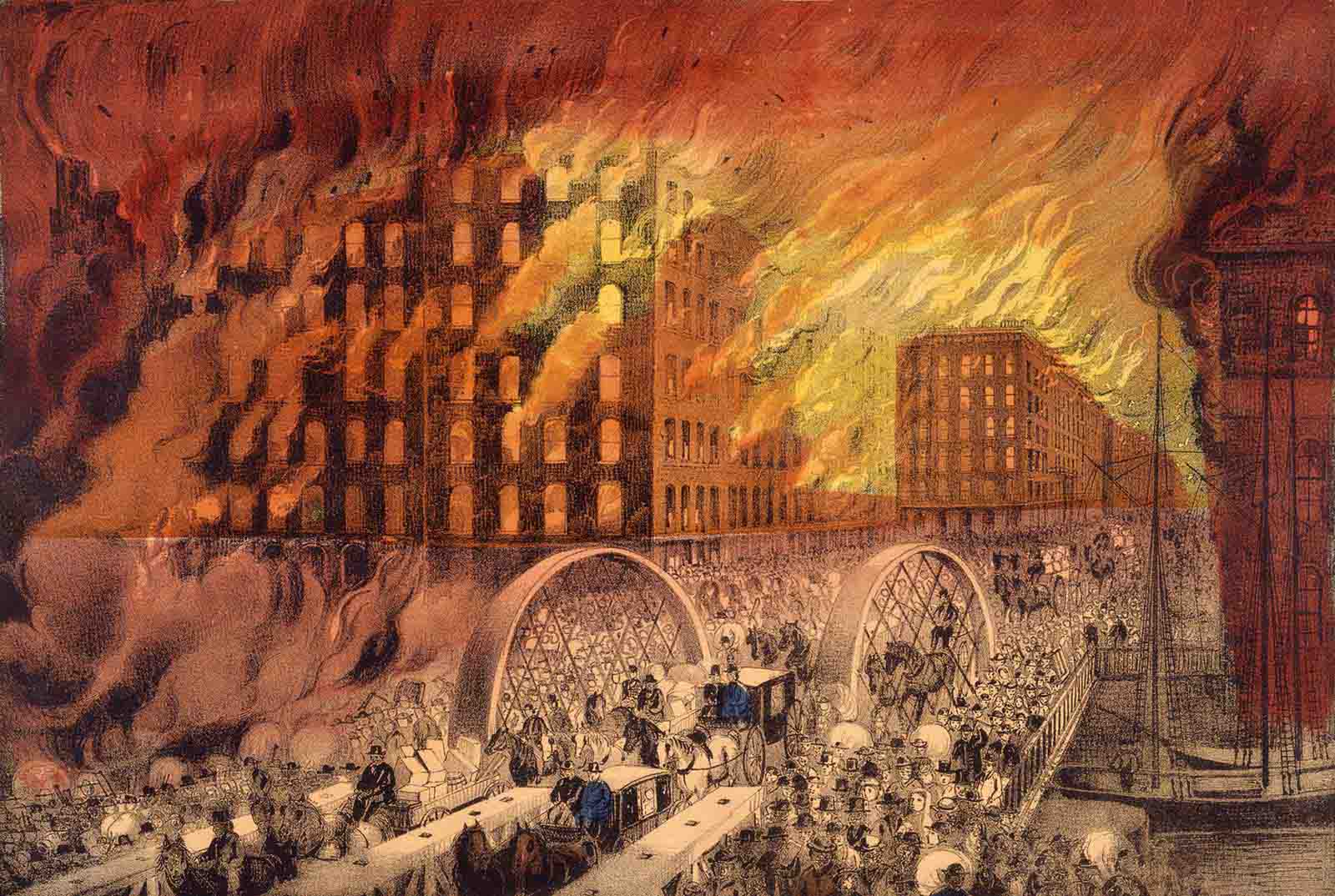

The people of Chicago were chased out of their city by one of the most destructive fires the world had ever seen, an event that came to be known in history as “The Great Chicago Fire”. The wall of flames roared and rumbled with a terrifying noise. Burning debris rose into the air on hurricane-like winds. The fire raced with speed that it literally nipped at the heels of those who ran from it. The inferno destroyed entire buildings in minutes. From the night of October 8 to the early morning of October 10, the Great Chicago Fire burned away the entire city, claiming more than 2,600 acres (1,052 hectares). In the end, the Great Fire destroyed 18,000 buildings, from the humble shacks of the poor to the finest brick and marble homes of the rich. The fire leveled banks, stores, hotels, railroad depots, courthouses, gasworks, waterworks, government buildings, newspaper publishing houses, opera houses, theaters, salons, restaurants, schools, and churches, nothing could stand in its way. Enormous lumber mills, grain elevators, coal yards, breweries, warehouses, and factories of all kinds were burned to the ground. Priceless works of art, museums, and libraries were devoured. Countless numbers of pets, wild animals, and livestock were lost. Amazingly, less than 300 people were killed in the fire. But afterward, more than 90,000 people were left without shelter, food, water, or anything more than clothes they were wearing or the few precious possessions they managed to carry with them at the last minute. People looked for someone, or something, to blame: foreing anarchists trying to overthrow the government; irresponsible firefighters who had been drinking; and, most famous, Mrs. O’Leary’s cow who knocked over an oil lantern, setting the barn ablaze. None of these are true. The sad fact is Chicago was a city that was just waiting to burn down. The fire is claimed to have started at about 8:30 p.m. on October 8, in or around a small barn belonging to the O’Leary family that bordered the alley behind 137 DeKoven Street. The shed next to the barn was the first building to be consumed by the fire. City officials never determined the cause of the blaze, but the rapid spread of the fire due to a long drought in that year’s summer, strong winds from the southwest, and the rapid destruction of the water pumping system, explain the extensive damage of the mainly wooden city structures. The fire’s spread was aided by the city’s use of wood as the predominant building material in a style called balloon frame. More than two-thirds of the structures in Chicago at the time of the fire were made entirely of wood, with most of the houses and buildings being topped with highly flammable tar or shingle roofs. All of the city’s sidewalks and many roads were also made of wood. In 1871, the Chicago Fire Department had 185 firefighters with just 17 horse-drawn steam pumpers to protect the entire city. The initial response by the fire department was quick, but due to an error by the watchman, Matthias Schaffer, the firefighters were sent to the wrong place, allowing the fire to grow unchecked. As more buildings succumbed to the flames, a major contributing factor to the fire’s spread was a meteorological phenomenon known as a fire whirl. As overheated air rises, it comes into contact with cooler air and begins to spin creating a tornado-like effect. These fire whirls are likely what drove flaming debris so high and so far. Late into the evening of October 9, it started to rain, but the fire had already started to burn itself out. The fire had spread to the sparsely populated areas of the north side, having consumed the densely populated areas thoroughly. In the days and weeks following the fire, monetary donations flowed into Chicago from around the country and abroad, along with donations of food, clothing, and other goods. These donations came from individuals, corporations, and cities. The Great Chicago Fire led to questions about development in the United States. Due to Chicago’s rapid expansion at that time, the fire led to Americans reflecting on industrialization. Almost immediately, the city began to rewrite its fire standards, and soon Chicago developed one of the country’s leading fire-fighting forces.

(Photo credit: Chicago History Museum / Wikimedia Commons / The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 by Christy Marx). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe