The gift was meant as a gesture of friendship to the USSR’s World War II ally and was hung in the ambassador’s official residence at Spaso House in Moscow. For seven years, it adorned the study wall until a discovery was made by the State Department: the seal was more than a mere decoration; it was a bug. The Soviets had cleverly built a listening device, nicknamed “The Thing” by the U.S. intelligence community, into the replica seal. They had been eavesdropping on Harriman and his successors the entire time it was in the house.

How Was The Great Seal Bug Designed?

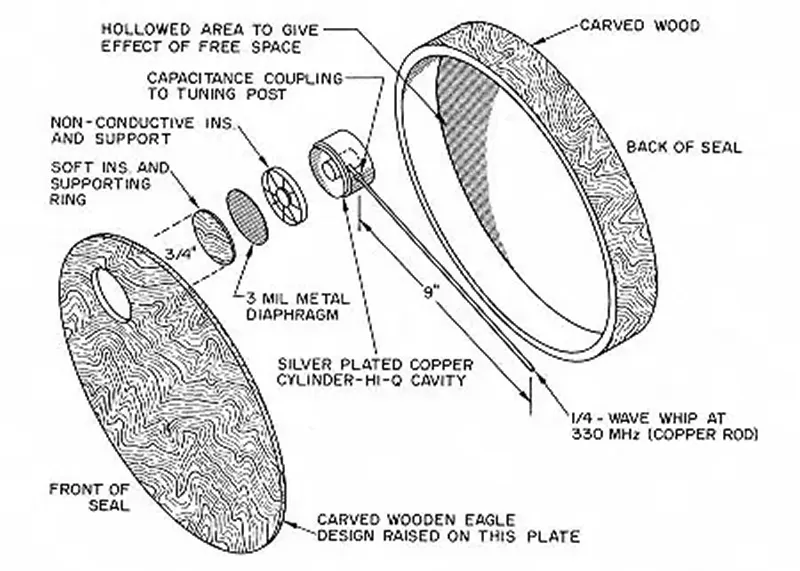

The Thing consisted of a tiny capacitive membrane connected to a small quarter-wavelength antenna; it had no power supply or active electronic components. The device, a passive cavity resonator, became active only when a radio signal of the correct frequency was sent to the device from an external transmitter. This is referred to in NSA parlance as “illuminating” a passive device. The device consisted of a 9-inch-long (23 cm) monopole antenna and it used a straight rod, led through an insulating bushing into a cavity, where it was terminated with a round disc that formed one plate of a capacitor. The cavity was a high-Q round silver-plated copper “can”. Its front side was closed with a very thin and fragile conductive membrane. In the middle of the cavity was a mushroom-shaped flat-faced tuning post, with its top adjustable to make it possible to set the membrane-post distance. The post had machined grooves and radial lines into its face, probably to provide channels for airflow to reduce pneumatic damping of the membrane. The antenna was capacitively coupled to the post via its disc-shaped end. The total weight of the unit, including the antenna, was 1.1 ounces (31 grams). The length of the antenna and the dimensions of the cavity were engineered in order to make the re-broadcast signal a higher harmonic of the illuminating frequency. The original device was located with the can under the beak of the eagle on the Great Seal presented to W. Averell Harriman; accounts differ on whether holes were drilled into the beak to allow sound waves to reach the membrane. Other sources say the wood behind the beak was undrilled but thin enough to pass the sound, or that the hollowed space acted like a soundboard to concentrate the sound from the room onto the microphone. Its design made the listening device very difficult to detect, because it was very small, had no power supply or active electronic components, and did not radiate any signal unless it was actively being irradiated remotely. These same design features, along with the overall simplicity of the device, made it very reliable and gave it a potentially unlimited operational life.

Discovery and the Aftermath

The Thing was designed by Soviet Russian inventor Leon Theremin, best known for his invention of the theremin, an electronic musical instrument. Disguised within a finely carved wooden plaque of the Great Seal of the United States, this sophisticated apparatus enabled the Soviet government to eavesdrop on US communications. Remarkably, on August 4, 1945, just weeks before the conclusion of World War II, members of the Young Pioneer Organization of the Soviet Union presented this bugged carving to Ambassador Harriman, ostensibly as a “gesture of friendship” to their war ally. For seven years, it remained discreetly suspended in the ambassador’s study within his Moscow residence until its exposure in 1952 during Ambassador George F. Kennan’s tenure. In 1951, the existence of the bug came to light through a fortuitous discovery. A British radio operator stationed at the British Embassy happened upon American conversations on an open Soviet Air Force radio channel, which inadvertently intercepted radio waves aimed at the ambassador’s office. Subsequently, an American State Department employee replicated the incident using a basic untuned wideband receiver, akin to some field strength meters, equipped with a simple diode detector/demodulator. With mounting suspicions of espionage, two additional State Department employees, John W. Ford and Joseph Bezjian, were dispatched to Moscow in March 1951. Their mission involved investigating suspected bugs in the British and Canadian embassy buildings. To ascertain the presence of covert surveillance devices, they conducted a thorough counter surveillance “sweep” of the ambassador’s office. Employing a signal generator and a receiver in a setup that generates audio feedback (“howl”) upon transmitting sound from the room at a given frequency, Bezjian made a significant breakthrough. It was during this meticulous sweep that he stumbled upon the hidden eavesdropping device secreted within the intricate Great Seal carving. The Federal Bureau of Investigation, Central Intelligence Agency, the Naval Research Laboratory, and other U.S. agencies analyzed the device, along with assistance from the British government agency MI5 and the British Marconi Company. Marconi technician Peter Wright, a British scientist and later MI5 counterintelligence officer, ran the investigation. He was able to get The Thing working reliably with an illuminating frequency of 800 MHz. The generator which had discovered the device was tuned to 1800 MHz. The simplicity of the device caused some initial confusion during its analysis; the antenna and resonator had several resonant frequencies in addition to its main one, and the modulation was partially both amplitude modulated and frequency modulated. The team also lost some time on an assumption that the distance between the membrane and the tuning post needed to be increased to increase resonance. In May 1960, The Thing was mentioned on the fourth day of meetings in the United Nations Security Council, convened by the Soviet Union over the 1960 U-2 incident where a U.S. spy plane had entered their territory and been shot down. The U.S. ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. showed off the bugging device in the Great Seal to illustrate that spying incidents between the two nations were mutual and to allege that Nikita Khrushchev had magnified this particular incident as a pretext to abort the 1960 Paris Summit: “I produced a wooden carving of the Great Seal of the United States which was given by some Russians to the United States Ambassador to the Soviet Union and which hung in his office behind his desk. And which contained an electronic device which made it possible for persons on the outside possessing a certain type of technical device to hear everything that went on. I produced that as a piece of evidence, and it is direct, fresh, authentic evidence, to show the effectiveness and the thoroughness of Soviet espionage.”

(Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / CIA Declassified Materials). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe