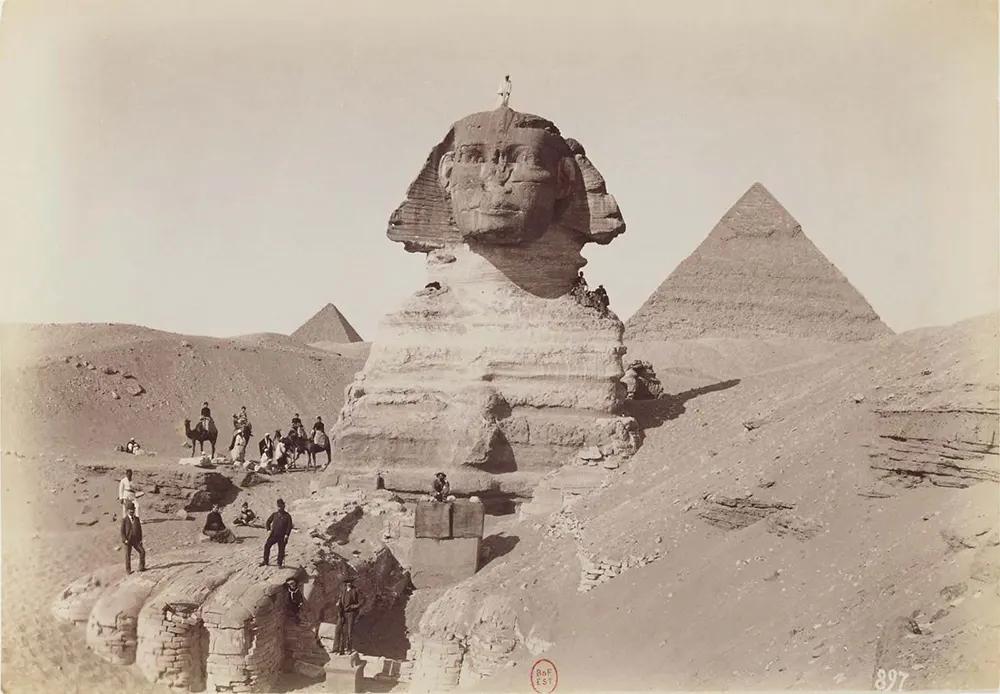

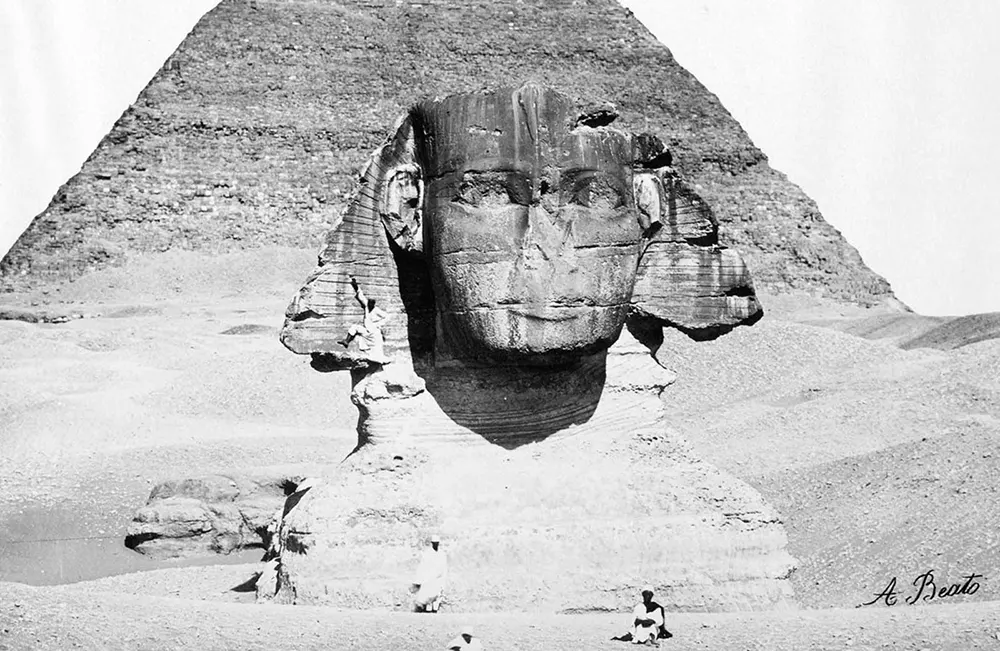

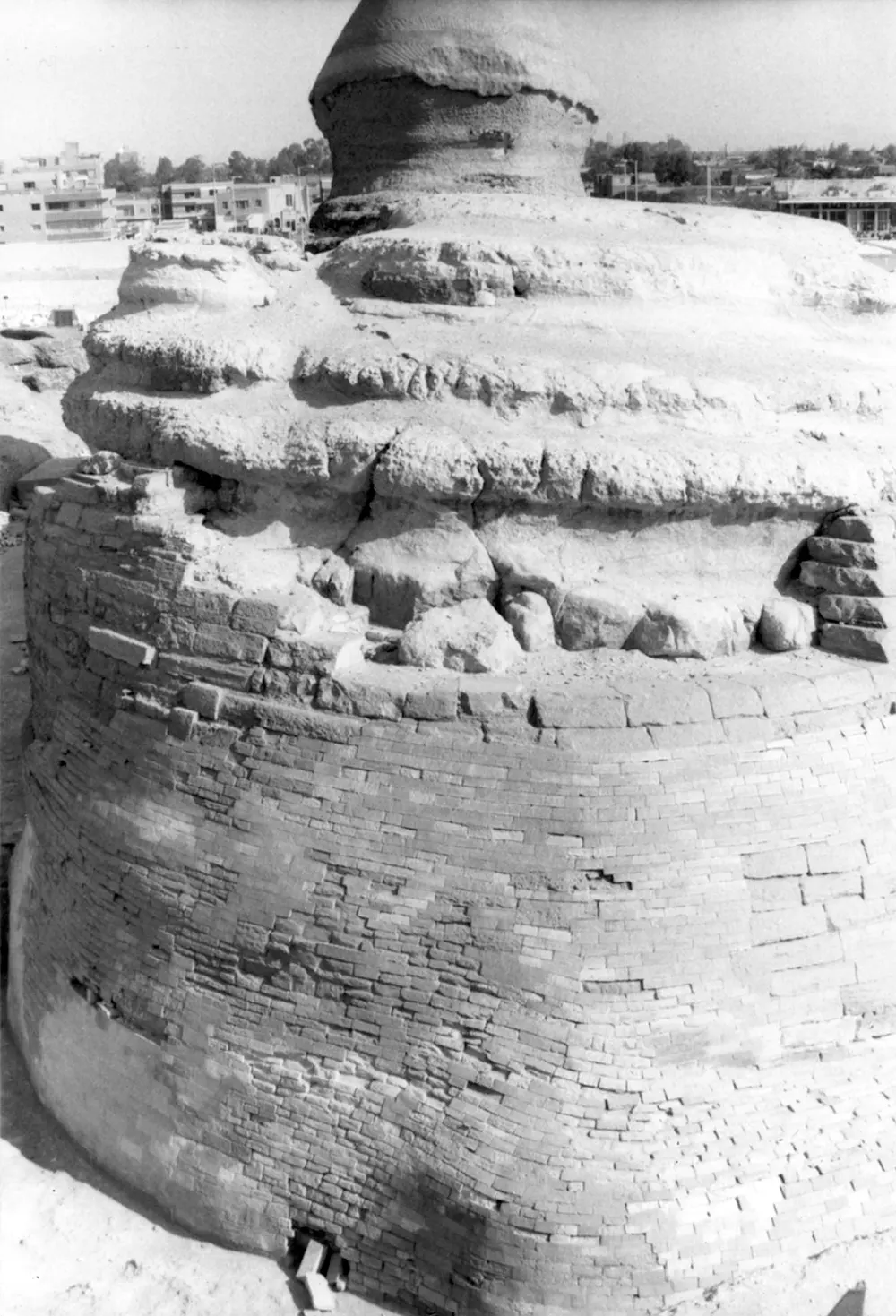

Even the ancient Egyptians themselves were puzzled by the remote antiquity and purpose of the Great Sphinx at Giza. Gathered in this article are various vintage photographs of the Sphinx throughout the past 170 years. The commonly used name “Sphinx” was given to it in classical antiquity, about 2,000 years after the commonly accepted date of its construction by reference to a Greek mythological beast with the head of a woman, a falcon, a cat, or a sheep and the body of a lion with the wings of an eagle. (although, like most Egyptian sphinxes, the Great Sphinx has a man’s head and no wings). The Sphinx is a monolith carved from the bedrock of the plateau, which also served as the quarry for the pyramids and other monuments in the area. Egyptian geologist Farouk El-Baz has suggested that the head of the Sphinx may have been carved first, out of a natural yardang, i.e. a ridge of bedrock that had been sculpted by the wind. The archeological evidence suggests that the Great Sphinx was created around 2500 BC for the pharaoh Khafre, the builder of the Second Pyramid at Giza. The stones cut from around the Sphinx’ body were used to construct a temple in front of it, however, both the enclosure and this temple were never completed. Sometime around 2100 BC, the Giza Necropolis was abandoned, and drifting sand eventually buried the Sphinx up to its shoulders. The first documented attempt at an excavation dates to c. 1400 BC, when the young Thutmose IV (1401–1391 or 1397–1388 BC) gathered a team and, after much effort, managed to dig out the front paws. In Graeco-Roman times, Giza had become a tourist destination—the monuments were regarded as antiquities—and some Roman Emperors visited the Sphinx out of curiosity, and for political reasons. The Sphinx was cleared of sand again in the first century AD in honor of Emperor Nero and the Governor of Egypt Tiberius Claudius Balbilus. A monumental stairway—more than 12 meters (39 ft) wide—was erected, leading to a pavement in front of the paws of the Sphinx. At the top of the stairs, a podium was positioned that allowed view into the Sphinx sanctuary. Pliny the Elder describes the face of the Sphinx being colored red and gives measurements for the statue: In front of these pyramids is the Sphinx, a still more wondrous object of art, but one upon which silence has been observed, as it is looked upon as a divinity by the people of the neighborhood. It is their belief that King Harmaïs was buried in it, and they will have it that it was brought there from a distance. The truth is, however, that it was hewn from the solid rock; and, from a feeling of veneration, the face of the monster is colored red. The circumference of the head, measured around the forehead, is one hundred and two feet, the length of the feet being one hundred and forty-three, and the height, from the belly to the summit of the asp on the head, sixty-two. Over the centuries, writers and scholars have recorded their impressions and reactions upon seeing the Sphinx. The vast majority were concerned with a general description, often including a mixture of science, romance, and mystique. In 1817, the first modern archeological dig, supervised by the Italian Giovanni Battista Caviglia, uncovered the Sphinx’s chest completely. This is how he described the findings: At the beginning of the year 1887, the chest, the paws, the altar, and plateau were all made visible. Flights of steps were unearthed, and finally, accurate measurements were taken of the great figures. The height from the lowest of the steps was found to be one hundred feet, and the space between the paws was found to be thirty-five feet long and ten feet wide. Here there was formerly an altar; and a stele of Thûtmosis IV was discovered, recording a dream in which he was ordered to clear away the sand that even then was gathering around the site of the Sphinx. A modern examination of the Sphinx’s face shows that long rods or chisels were hammered into the nose area, one down from the bridge and another beneath the nostril, then used to pry the nose off towards the south, resulting in the one-meter wide nose still being lost to date. Mark Lehner, who performed an archeological study, concluded that it was intentionally broken with instruments at an unknown time between the 3rd and 10th centuries AD. In addition to the lost nose, a ceremonial pharaonic beard is thought to have been attached, although this may have been added in later periods after the original construction. Egyptologist Vassil Dobrev has suggested that had the beard been an original part of the Sphinx, it would have damaged the chin of the statue upon falling. The lack of visible damage supports his theory that the beard was a later addition. In 1926 the Sphinx was cleared of sand under the direction of Baraize, which revealed an opening to a tunnel at floor-level at the north side of the rump. It was subsequently closed by masonry veneer and nearly forgotten. More than fifty years later, the existence of the passage was recalled by three elderly men who had worked during the clearing as basket carriers. This led to the rediscovery and excavation of the rump passage, in 1980. The Great Sphinx of Giza is the oldest known monumental sculpture in Egypt and one of the most recognizable statues in the world. The archeological evidence suggests that it was created by ancient Egyptians of the Old Kingdom during the reign of Khafre (c. 2558–2532 BC). (Photo credit: Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons / New York Public Library / The Atlantic). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe