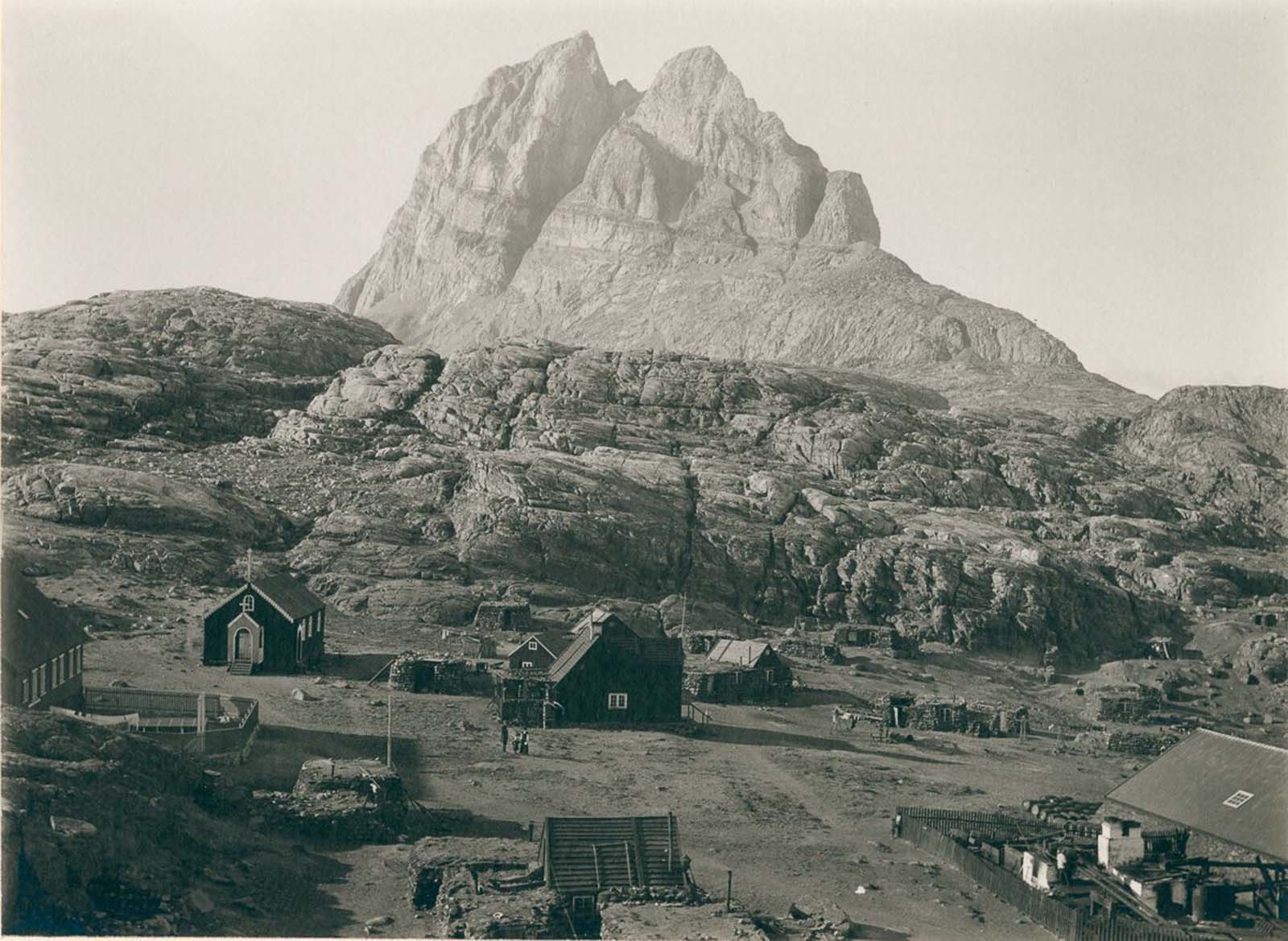

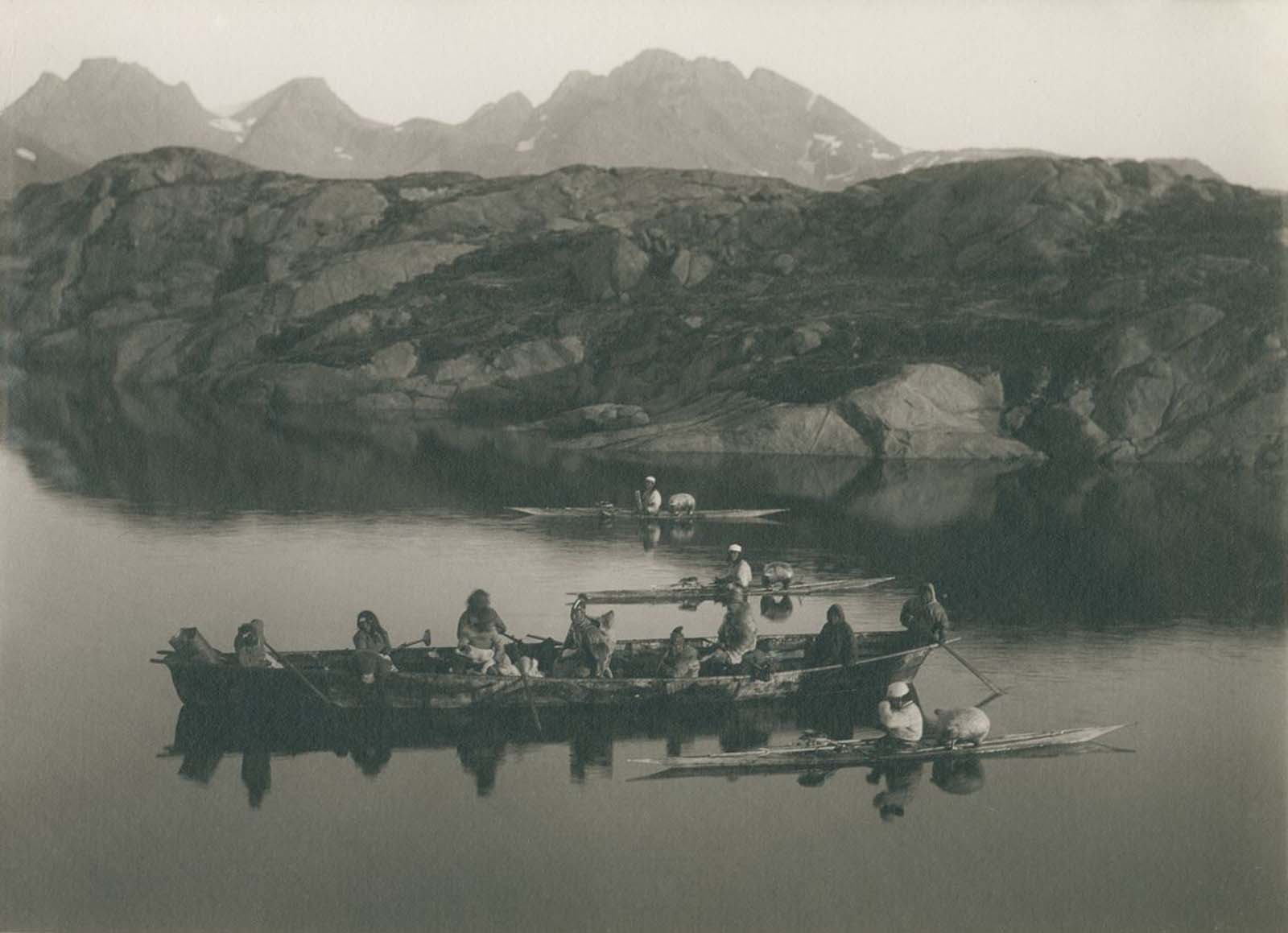

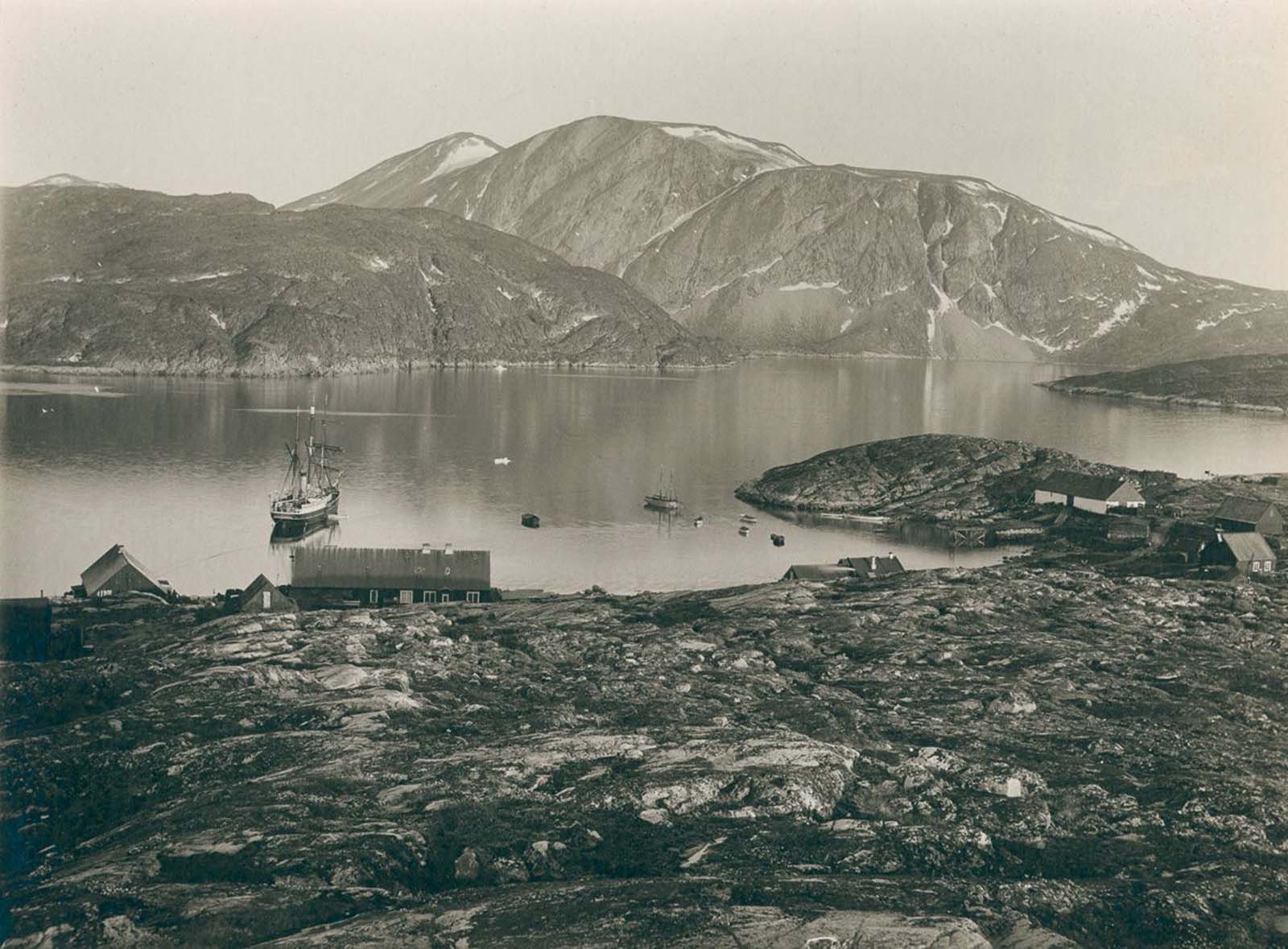

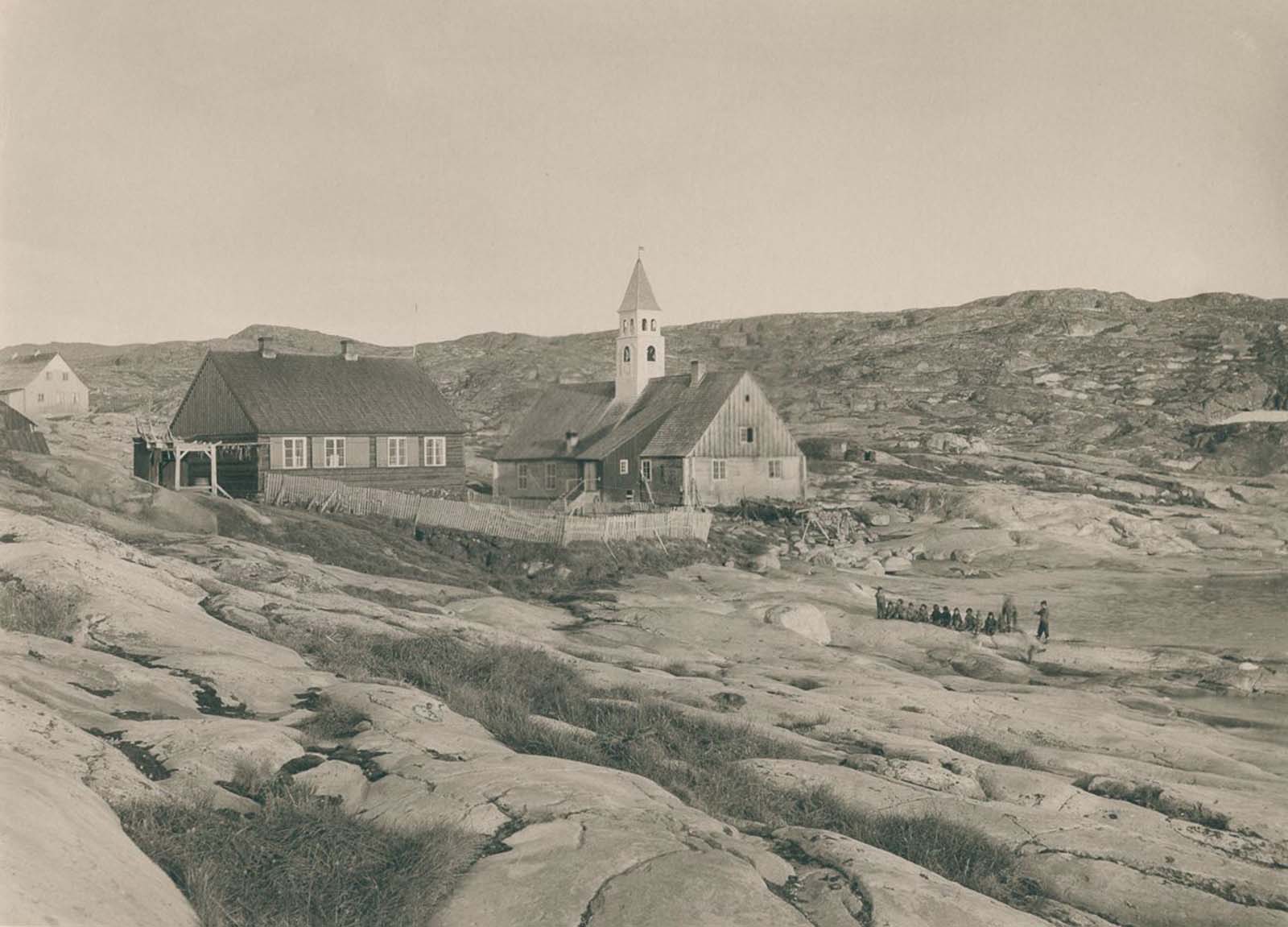

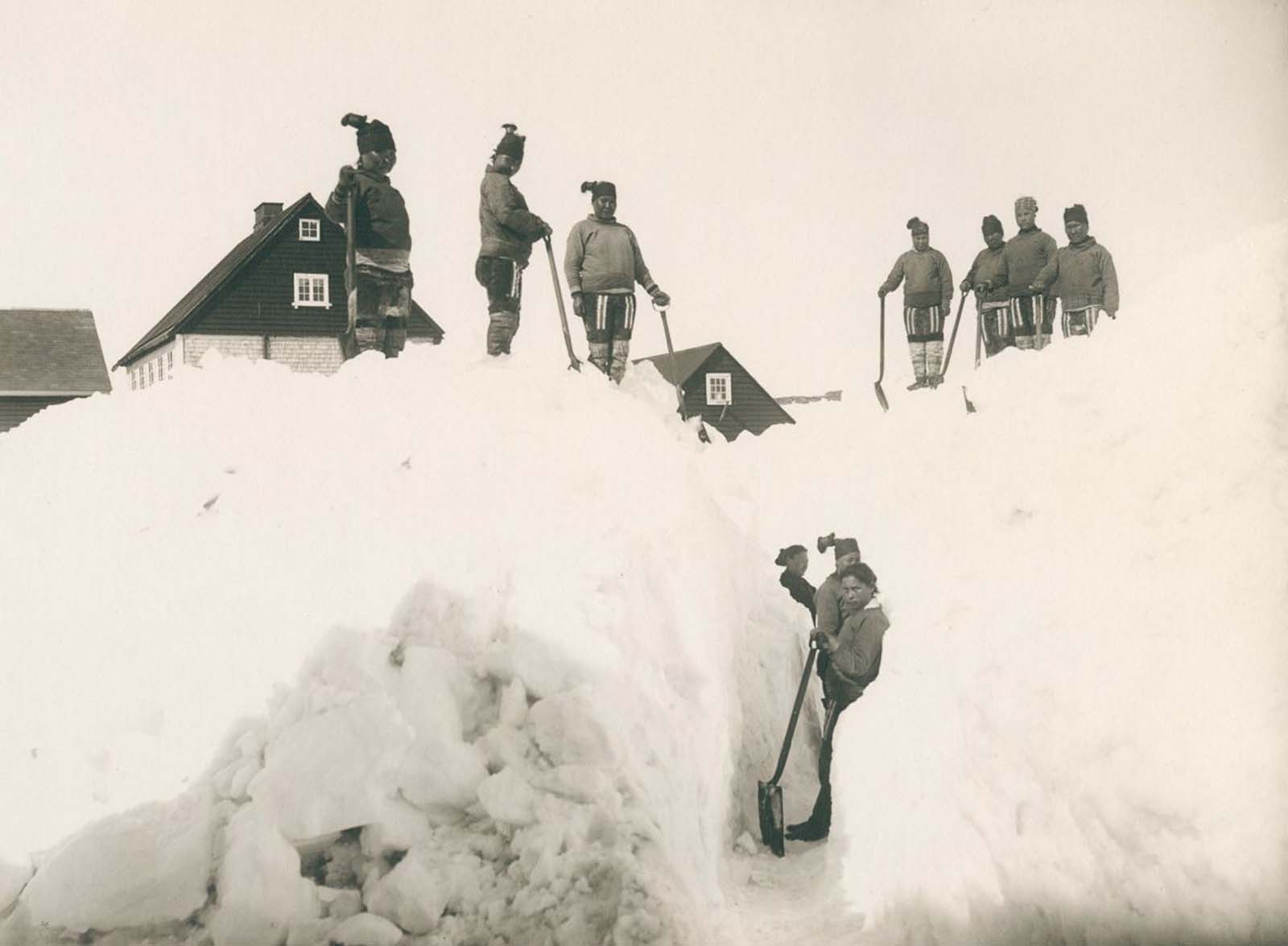

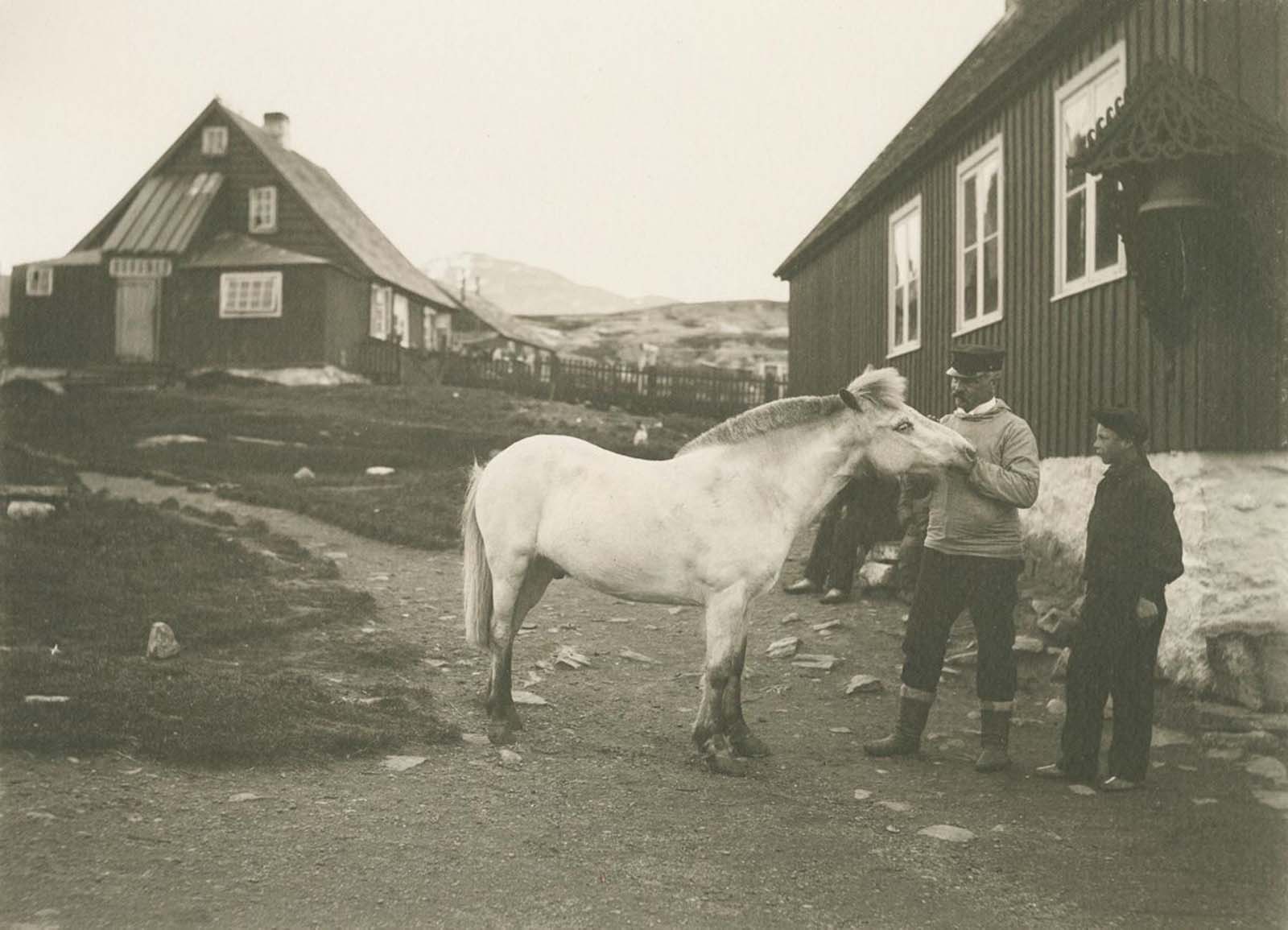

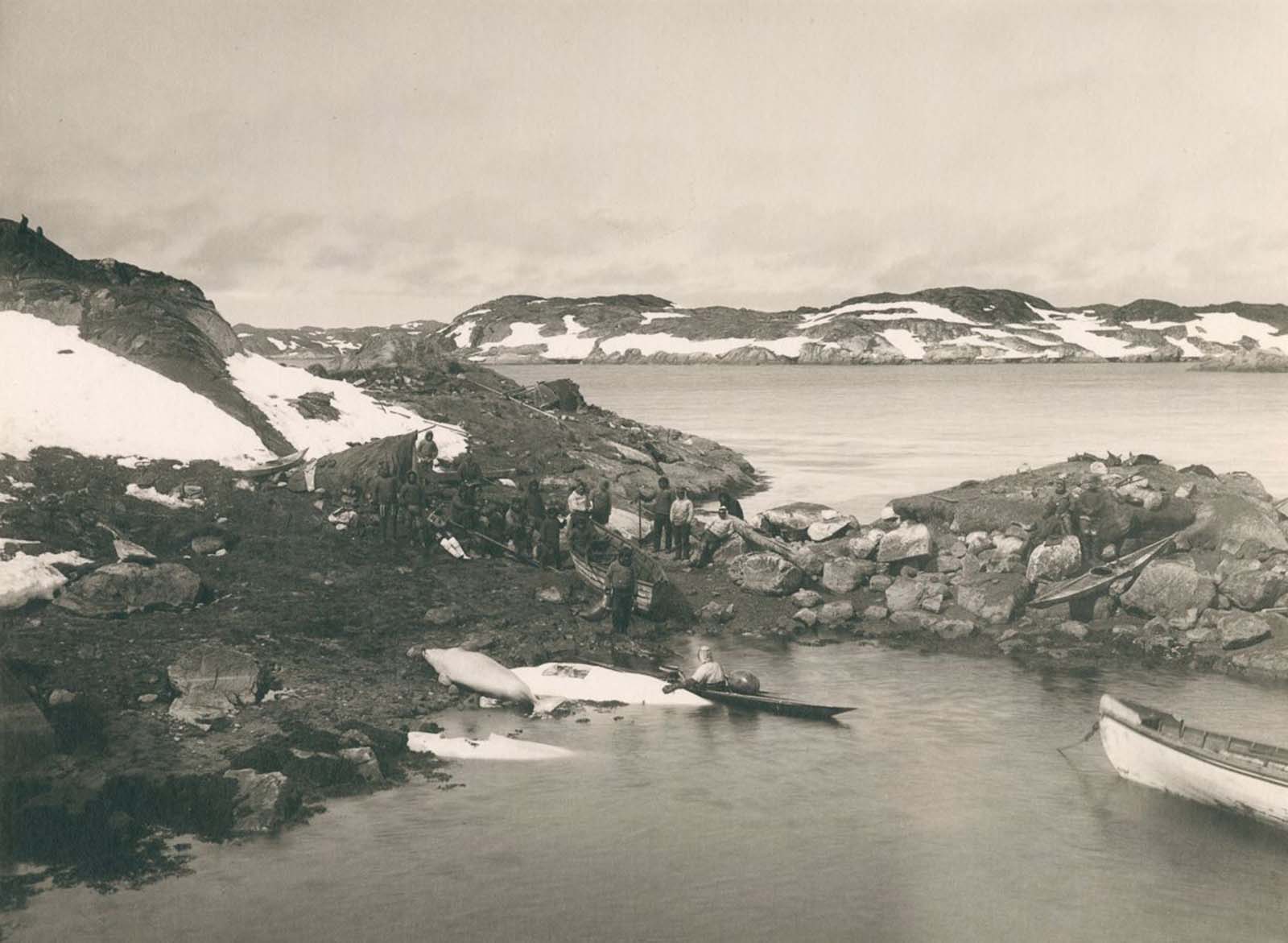

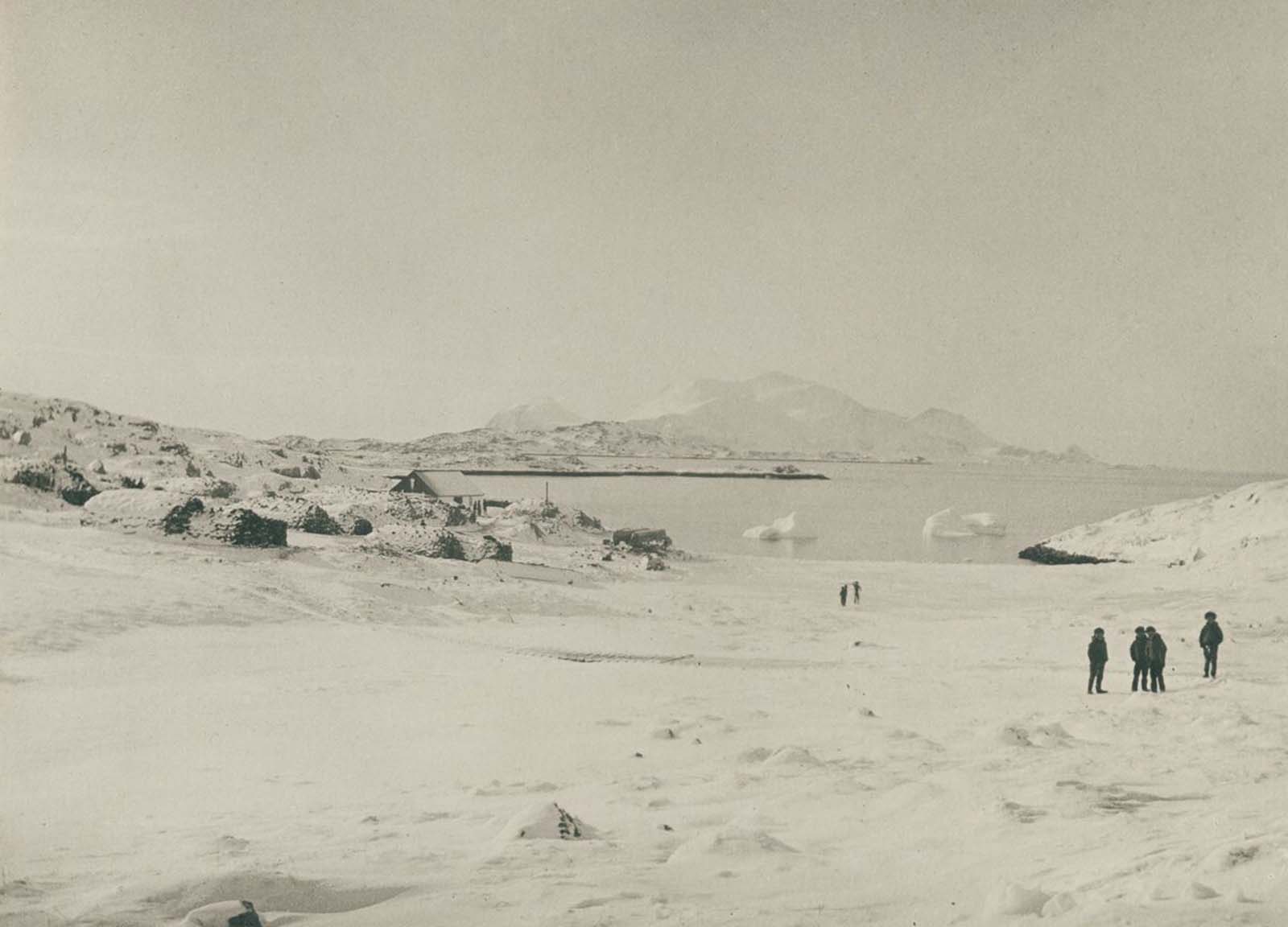

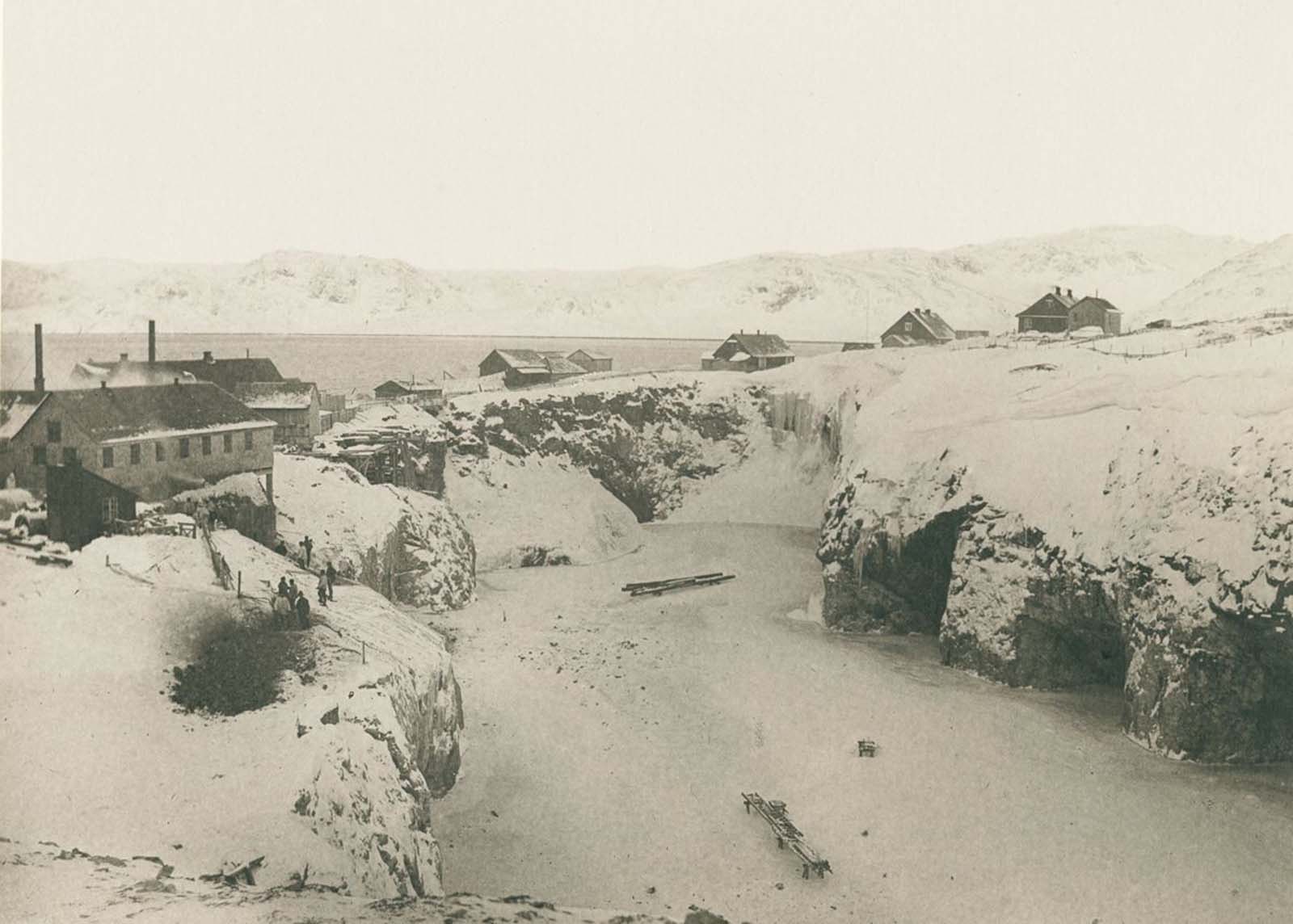

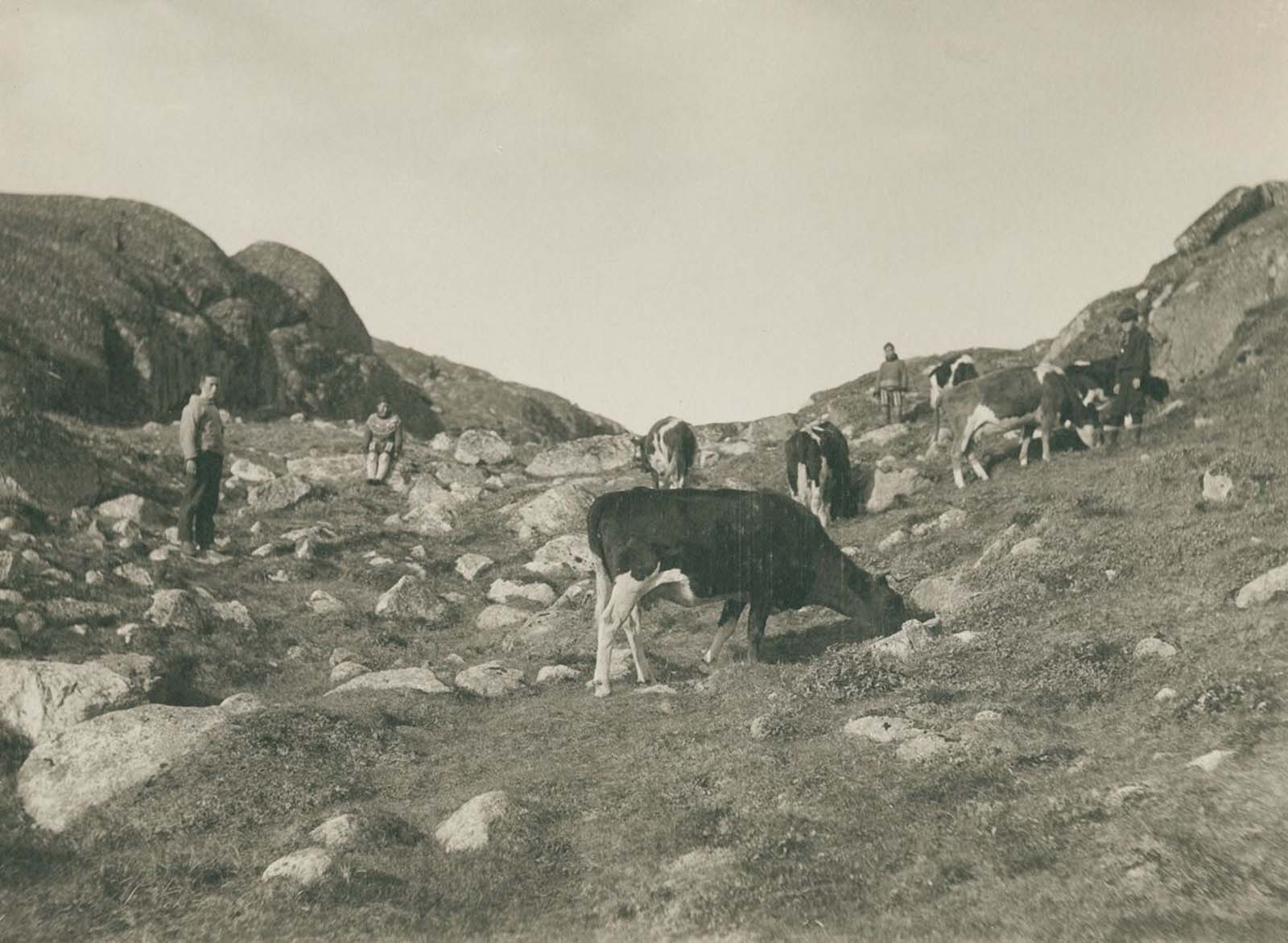

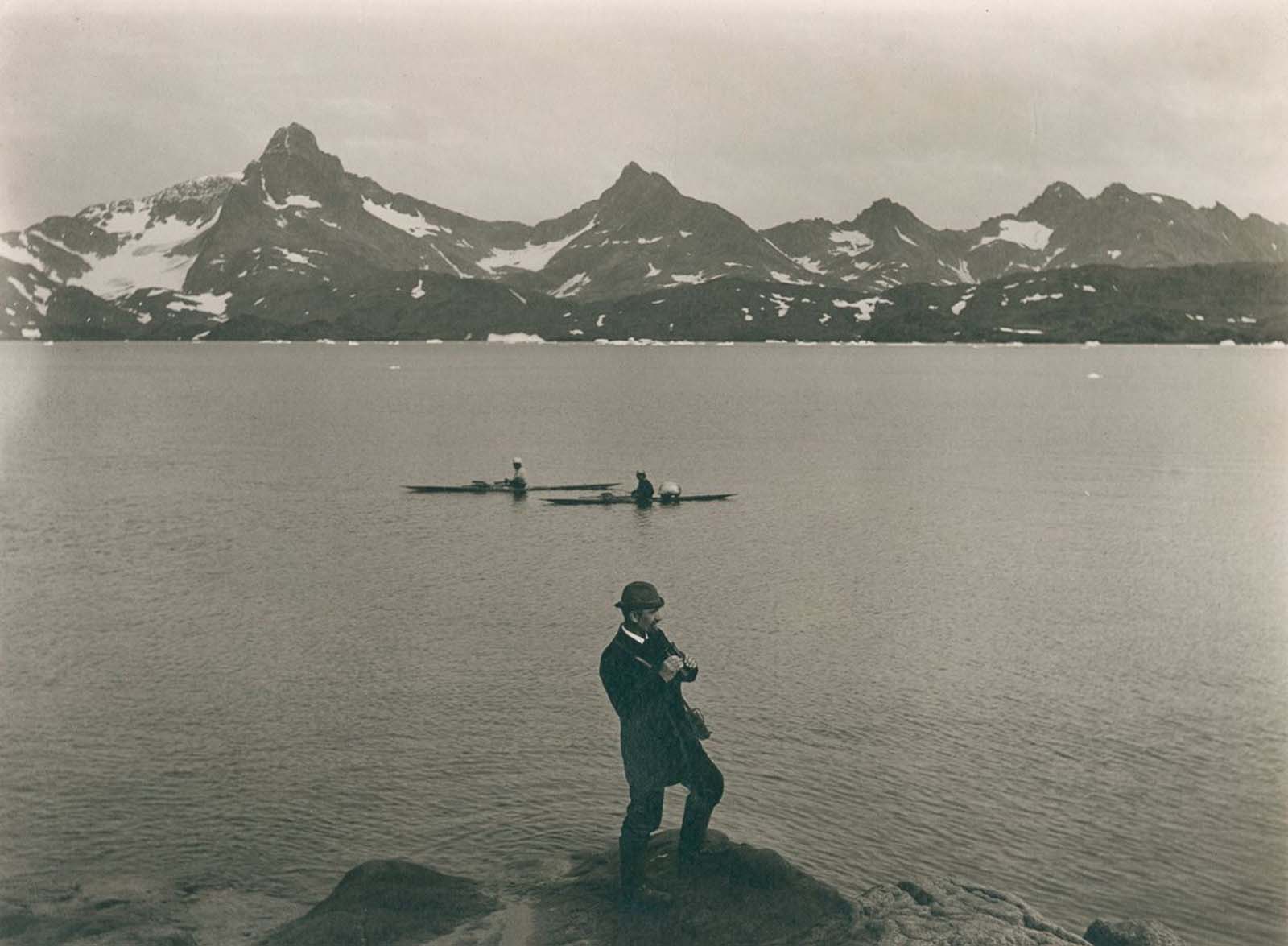

Greenland was unknown to Europeans until the 10th century when it was discovered by Icelandic Vikings. Before this discovery, it had been inhabited for a long time by Arctic peoples, although it was apparently unpopulated at the time when the Vikings arrived; the direct ancestors of the modern Inuit Greenlanders did not arrive until around 1200 from the northwest. The Viking settlements along the south-west coast eventually disappeared after about 450 years. The Inuit survived and developed a society to fit the increasingly forbidding climate (see Little Ice Age) and were the only people to inhabit the island for several hundred years. Denmark-Norway nonetheless claimed the territory, and after several centuries of no contact between the Viking Greenlanders and the Scandinavian motherland it was feared that they had lapsed back into paganism, so a missionary expedition was sent out to reinstate Christianity in 1721. However, since none of the lost Viking Greenlanders were found, Denmark-Norway instead proceeded to baptize the local Inuit Greenlanders and develop trading colonies along the coast as part of its aspirations as a colonial power. Colonial privileges were retained, such as trade monopoly. At the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century, American explorers, including Robert Peary, explored the northern sections of Greenland, which up to that time had been a mystery and were often shown on maps as extending over the North Pole. Peary discovered that Greenland’s northern coast in fact stopped well short of the pole. By 1911, the population was about 14,000, scattered along the southern shores. They were nearly all Christian, thanks to the missionary efforts of Moravians and especially Hans Egede, a Lutheran missionary called “the Apostle of Greenland.” (Photo credit: T.N. Krabbe / National Museum of Denmark). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe