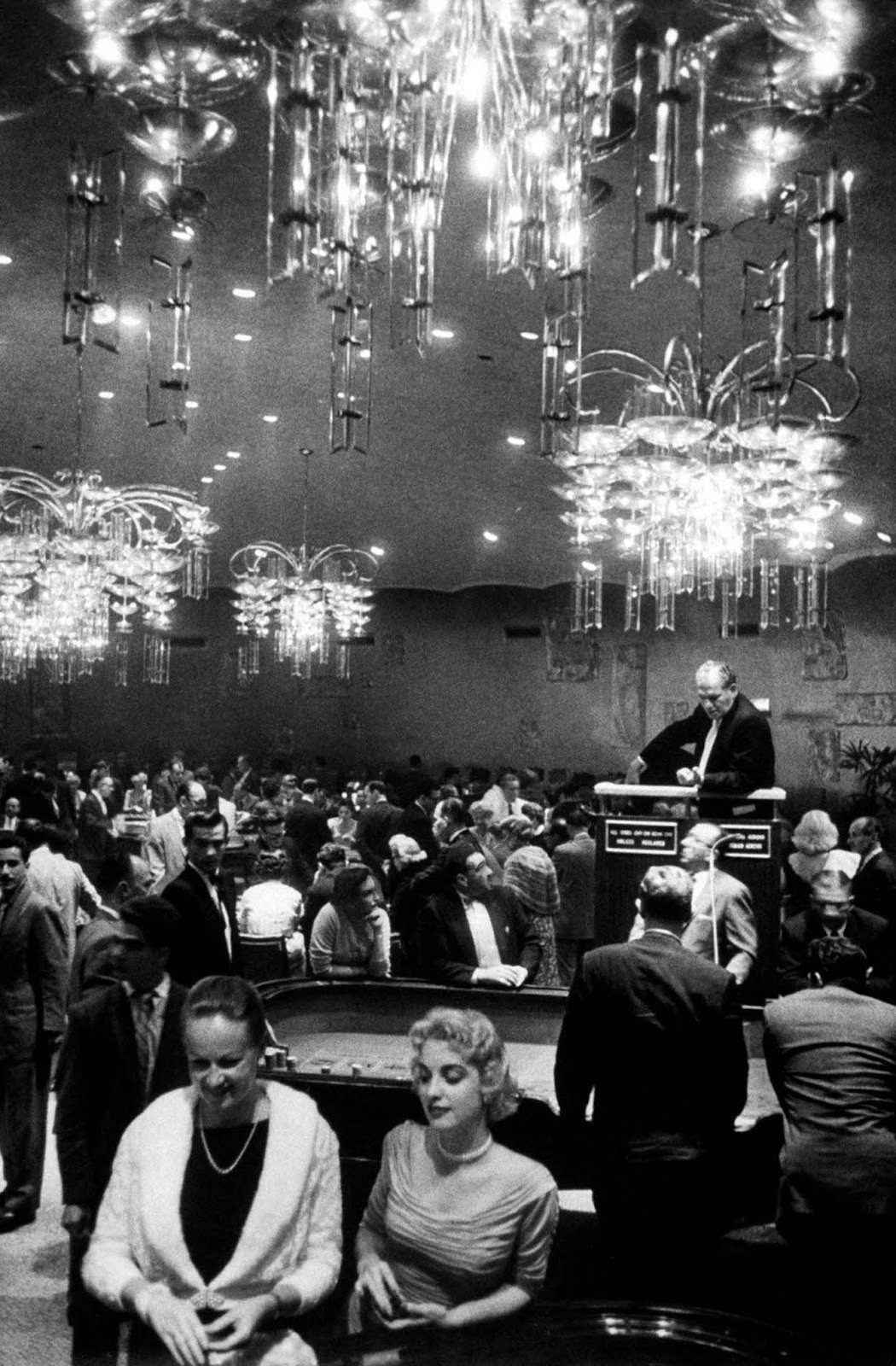

Sugar was Cuba’s economic lifeline, but its tropical beauty—and tropical beauties—made American tourism a natural and flowing source of revenue. A 1956 issue of Cabaret Quarterly, a now-defunct tourism magazine, describes Havana as “a mistress of pleasure, the lush and opulent goddess of delights”. What the tourists didn’t see, or didn’t want to, was the underclass, people of poverty like the macheteros — sugarcane cutters — who worked only during the four month season, and the rest of the year were unemployed and angry. “Havana was then what Las Vegas has become,” says Louis Perez, a Cuba historian. It attracted some of the same mafia kingpins, too, such as Meyer Lansky and Santo Trafficante, who were evading a national investigation into organized crime. In Cuba, they could continue their stock trade of gambling, drugs and prostitution, as long as they paid off government officials. The fees, however high, were a small price for an industry that raked in millions of dollars every month. But while tourists eagerly spun the roulette wheel in sexy Havana, a revolution brewed in the less glamorous countryside. The sugar boom that had fueled much of Cuba’s economic life was waning, and by the mid-’50s it was clear that expectations had exceeded results. With no reliable economic replacement in sight, Cubans began to feel the squeeze. Poverty, particularly in the provinces, increased. By the late ’50s, U.S. financial interests included 90 percent of Cuban mines, 80 percent of its public utilities, 50 percent of its railways, 40 percent of its sugar production, and 25 percent of its bank deposits—some $1 billion in total. American influence extended into the cultural realm, as well. Cubans grew accustomed to the luxuries of American life. They drove American cars, owned TVs, watched Hollywood movies, and shopped at Woolworth’s department store. The youth listened to rock and roll, learned English in school, adopted American baseball, and sported American fashions. In return, Cuba got hedonistic tourists, organized crime, and General Fulgencio Batista. In military power since the early 1930s, Batista appointed himself president by way of a military coup in 1952, dashing Cubans’ long-held hope for democracy. Not only was the economy weakening as a result of U.S. influence, but Cubans were also offended by what their country was becoming: a haven for prostitution, brothels and gambling. That degree of income inequality as well as accusations of corruption within the government of President Fulgencio Batista laid the groundwork for the Cuban Revolution, prompting an enduring economic embargo by the United States and the rapid end of Havana’s high-life. (Photo credit: The Life Picture Collection / Smithsonian). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe