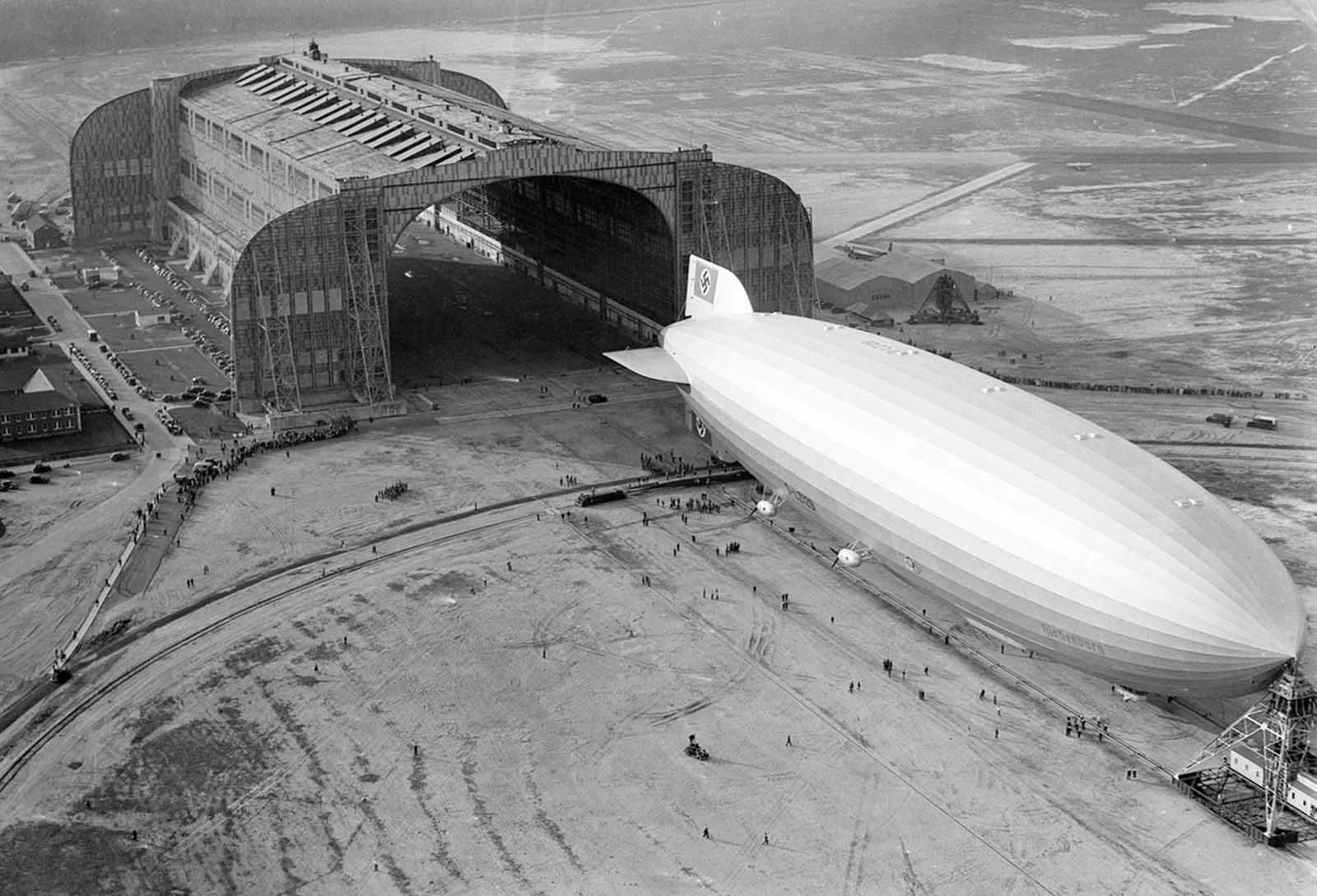

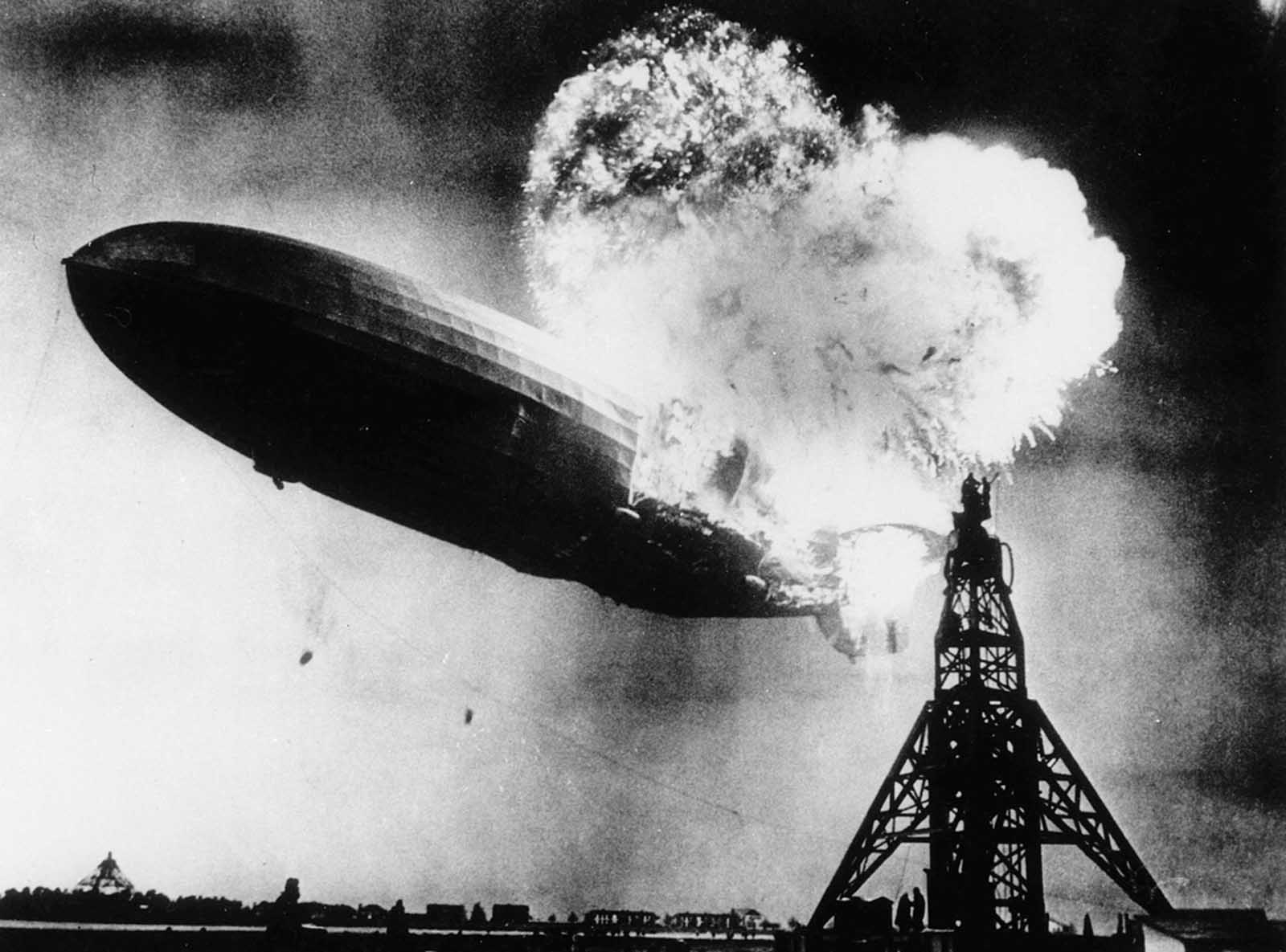

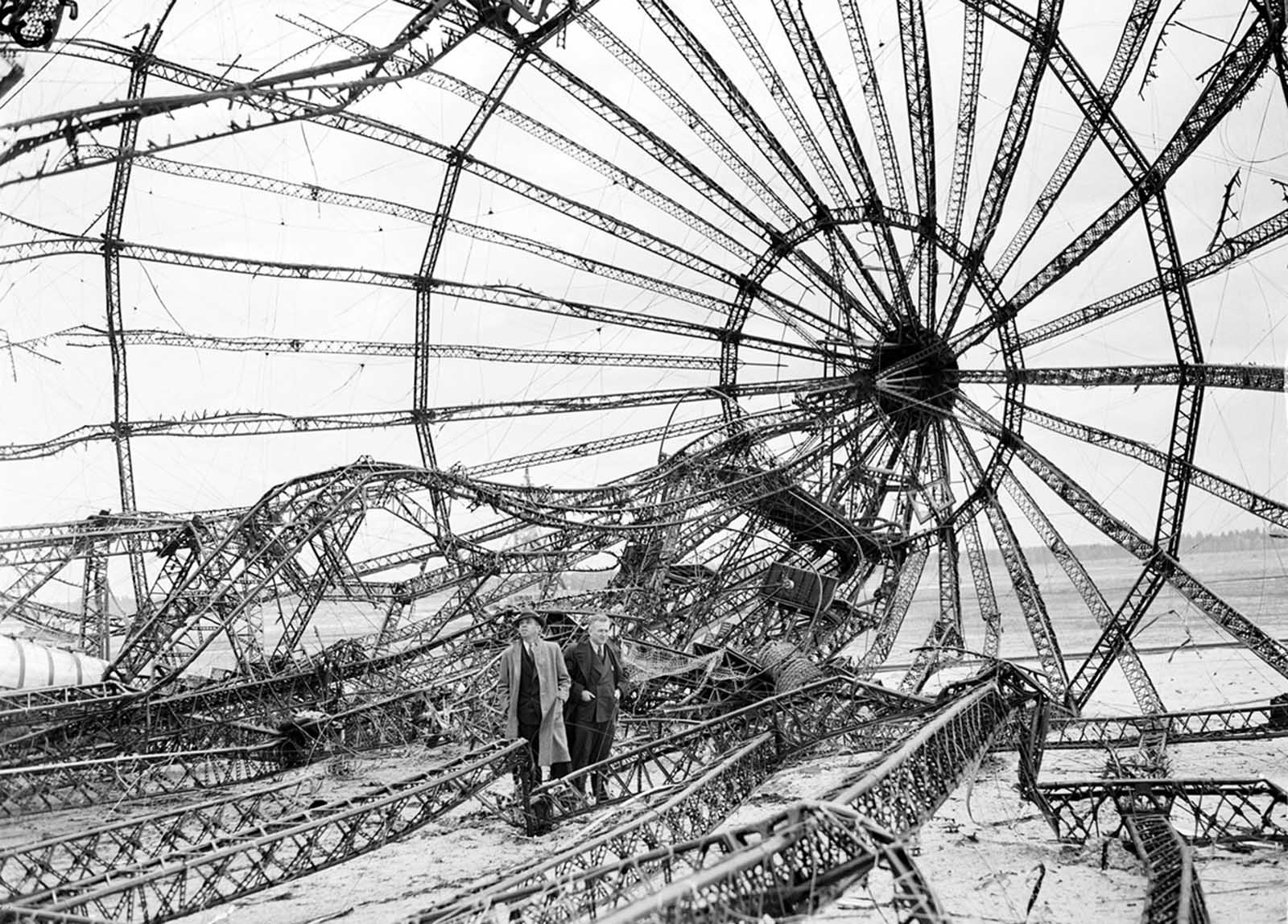

After more than 30 years of passenger travel on commercial zeppelins — in which tens of thousands of passengers flew over a million miles, on more than 2,000 flights, without a single injury — the era of the passenger airship came to an end in a few fiery minutes. Almost 80 years of research and scientific tests support the same conclusion reached by the original German and American accident investigations in 1937: It seems clear that the Hindenburg disaster was caused by an electrostatic discharge (i.e., a spark) that ignited leaking hydrogen. The spark was most likely caused by a difference in electric potential between the airship and the surrounding air: The airship was approximately 60 meters (about 200 feet) above the airfield in an electrically charged atmosphere, but the ship’s metal framework was grounded by its landing line. The difference in electric potential likely caused a spark to jump from the ship’s fabric covering (which had the ability to hold a charge) to the ship’s framework (which was grounded through the landing line). A somewhat less likely but still plausible theory attributes the spark to coronal discharge, more commonly known as St. Elmo’s Fire. The cause of the hydrogen leak is more of a mystery, but we know the ship experienced a significant leakage of hydrogen before the disaster. No evidence of sabotage was ever found, and no convincing theory of sabotaged has ever been advanced. One thing is clear: the disaster had nothing to do with the zeppelin’s fabric covering. Hindenburg was just one of many hydrogen airships destroyed by fire because of their flammable lifting gas, and suggestions about the alleged flammability of the ship’s outer covering have been repeatedly debunked. The simple truth is that Hindenburg was destroyed in 32 seconds because it was inflated with hydrogen. The disaster was the subject of spectacular newsreel coverage, photographs, and Herbert Morrison’s recorded radio eyewitness reports from the landing field, which were broadcast the next day. The event shattered public confidence in the giant, passenger-carrying rigid airship and marked the abrupt end of the airship era. (Photo credit: AP Photo / National Archves / Bundesarchiv / Library of Congress). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe