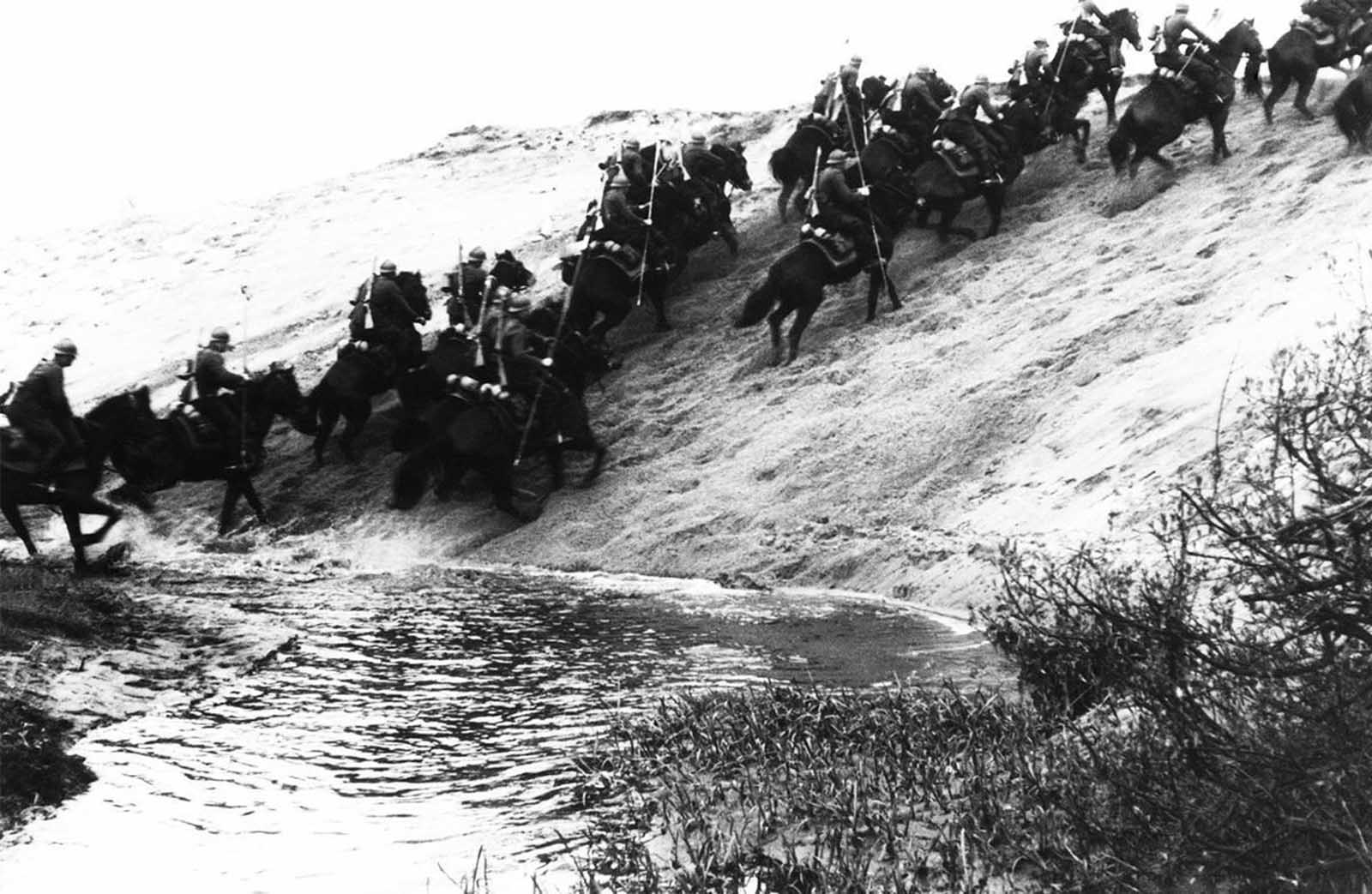

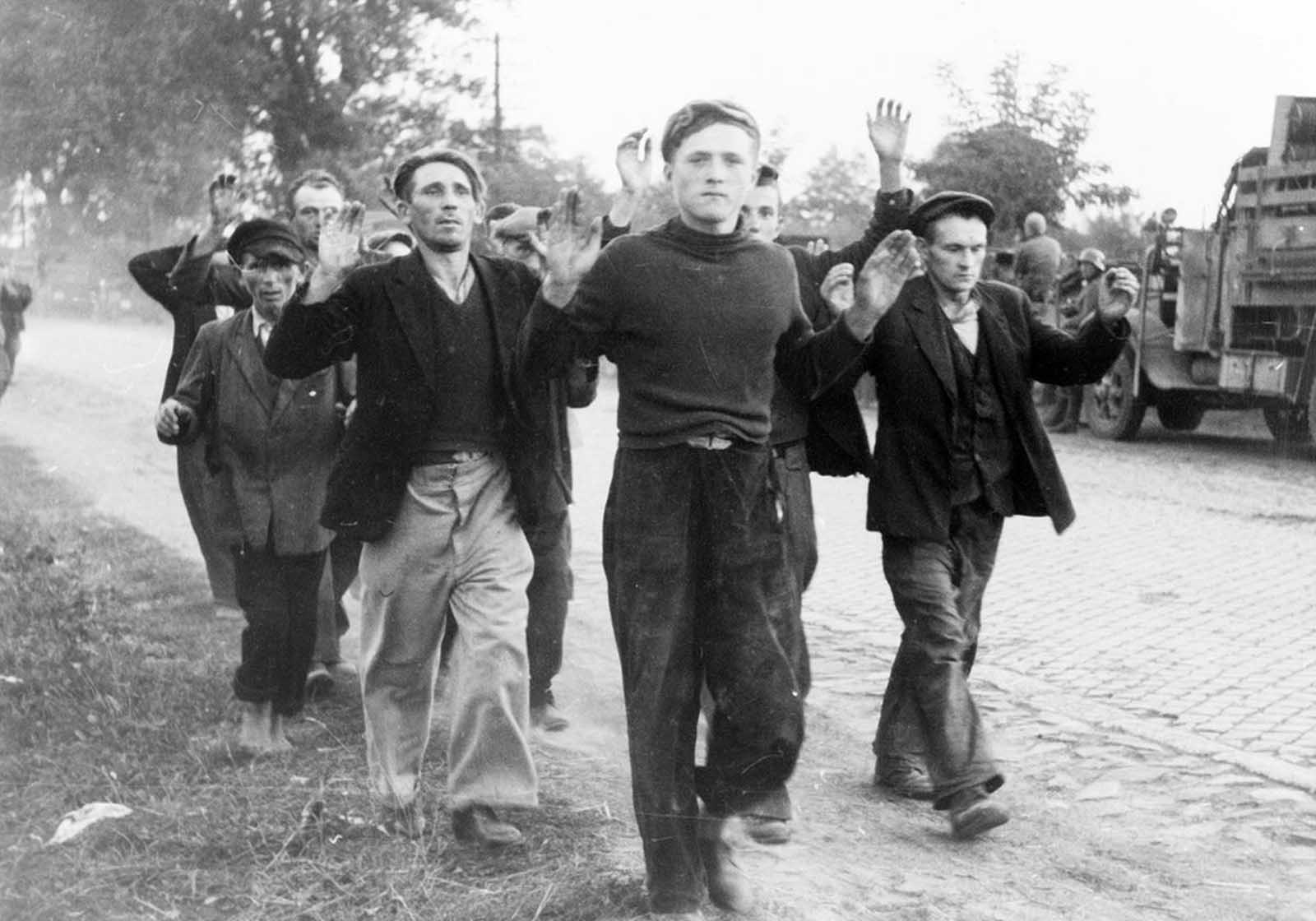

Recovering the ethnically Polish territory of Pomerania, Poznan, and Silesia, as well as the largely German Free City of Danzig were the major objectives. Nevertheless, the restrictions of Versailles and Germany’s internal weakness made such plans impossible to realize. Hitler’s rise to power in 1933 capitalized on German’s desire to regain lost territories, to which Nazi leaders added the goal of destroying an independent Poland. According to author Alexander Rossino, prior to the war Hitler was at least as anti-Polish as anti-Semitic in his opinions. After Hitler violated the Munich treaty, Poland was able to extract guarantees of military assistance from France, and significantly, Britain. In March 1939, Hitler began to make demands on Poland for the return of territory in the Polish Corridor, cessation of Polish rights in Danzig, and annexation of the Free City to Germany. These Poland categorically rejected. The war was close. On paper, Poland’s full mobilized army would have numbered about 2.5 million. Due to allied pressure and mismanagement, however, only about 600,000 Polish troops were in place to meet the German invasion on September 1, 1939. These forces were organized into 7 armies and 5 independent operational groups. The typical Polish infantry division was roughly equal in numbers to its German counterpart but weaker in terms of anti-tank guns, artillery support, and transport. Poland had 30 active and 7 reserve divisions. In addition, there were 12 cavalry brigades and one mechanized cavalry brigade. The Germans were organized into two Army Groups, with a total of 5 armies. The Germans fielded about 1.8 million troops. The Germans had 2600 tanks against the Polish 180, and over 2,000 aircraft against the Polish 420. German forces were supplemented by a Slovak brigade. German forces invaded Poland from the north, south, and west the morning after the Gleiwitz incident. Slovak forces advanced alongside the Germans in northern Slovakia. As the Wehrmacht advanced, Polish forces withdrew from their forward bases of operation close to the Polish–German border to more established lines of defense to the east. After the mid-September Polish defeat in the Battle of the Bzura, the Germans gained an undisputed advantage. Polish forces then withdrew to the southeast where they prepared for a long defense of the Romanian Bridgehead and awaited expected support and relief from France and the United Kingdom. While those two countries had pacts with Poland and had declared war on Germany on 3 September, in the end, their aid to Poland was very limited. The Soviet Red Army’s invasion of Eastern Poland on 17 September, in accordance with a secret protocol of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, rendered the Polish plan of defense obsolete. Facing a second front, the Polish government concluded the defense of the Romanian Bridgehead was no longer feasible and ordered an emergency evacuation of all troops to neutral Romania. On 6 October, following the Polish defeat at the Battle of Kock, German and Soviet forces gained full control over Poland. The success of the invasion marked the end of the Second Polish Republic, though Poland never formally surrendered. The American journalist John Gunther wrote in December 1939 that “the German campaign was a masterpiece. Nothing quite like it has been seen in military history”. Despite Poland’s poor leadership and outside assistance, Gunther still claimed that the invasion proved the skill of the German armed forces. The country was divided between Germany and the Soviet Union. Slovakia gained back those territories taken by Poland in autumn 1938. Lithuania received the city of Vilnius and its environs on 28 October 1939 from the Soviet Union. About 65,000 Polish troops were killed in the fighting, with 420,000 others being captured by the Germans and 240,000 more by the Soviets (for a total of 660,000 prisoners). Up to 120,000 Polish troops escaped to neutral Romania(through the Romanian Bridgehead and Hungary), and another 20,000 to Latvia and Lithuania, with the majority, eventually making their way to France or Britain. Most of the Polish Navy succeeded in evacuating to Britain as well. German personnel losses were less than their enemies (c. 16,000 killed). (Photo credit: Library of Congress / Bundesarchiv / AP). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe