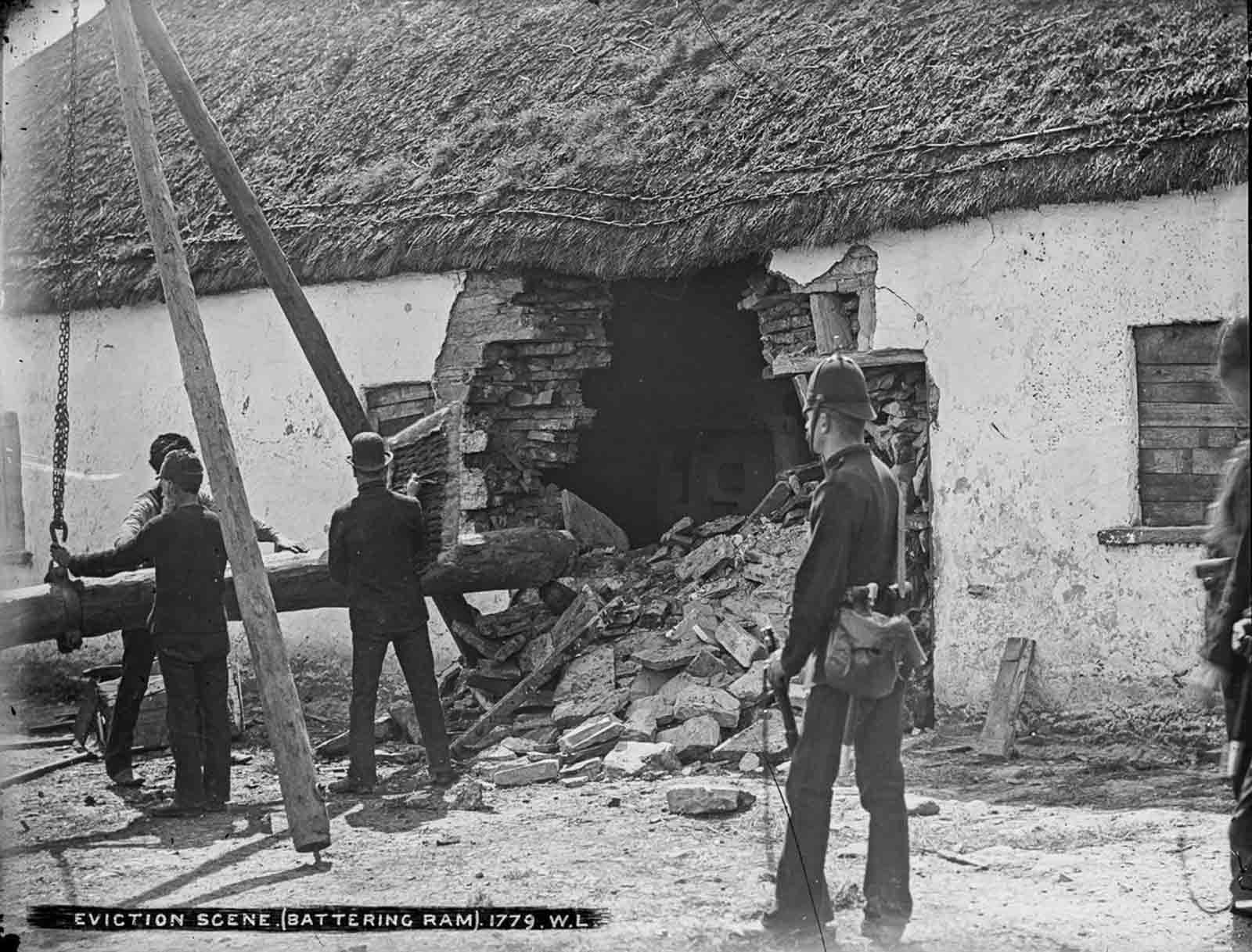

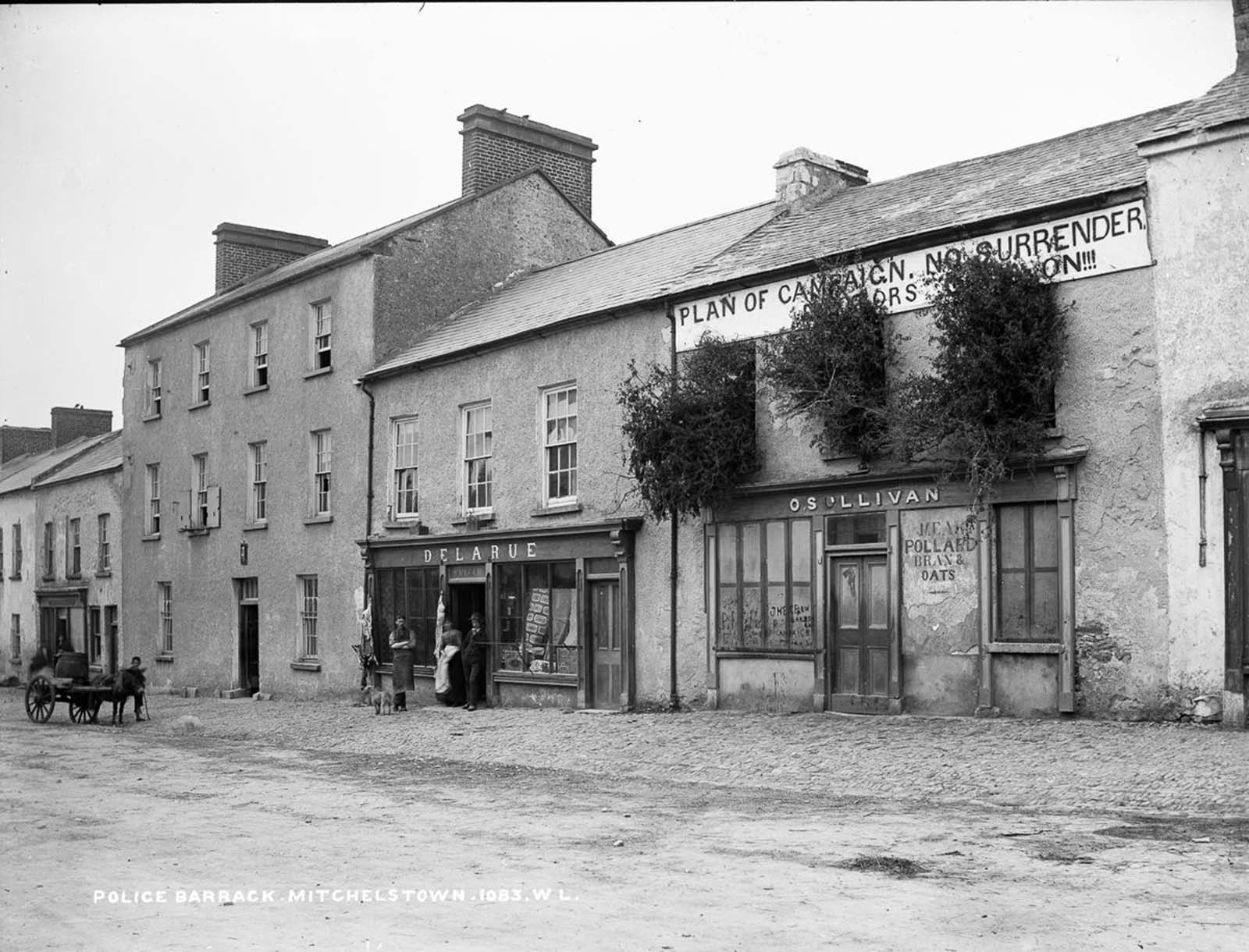

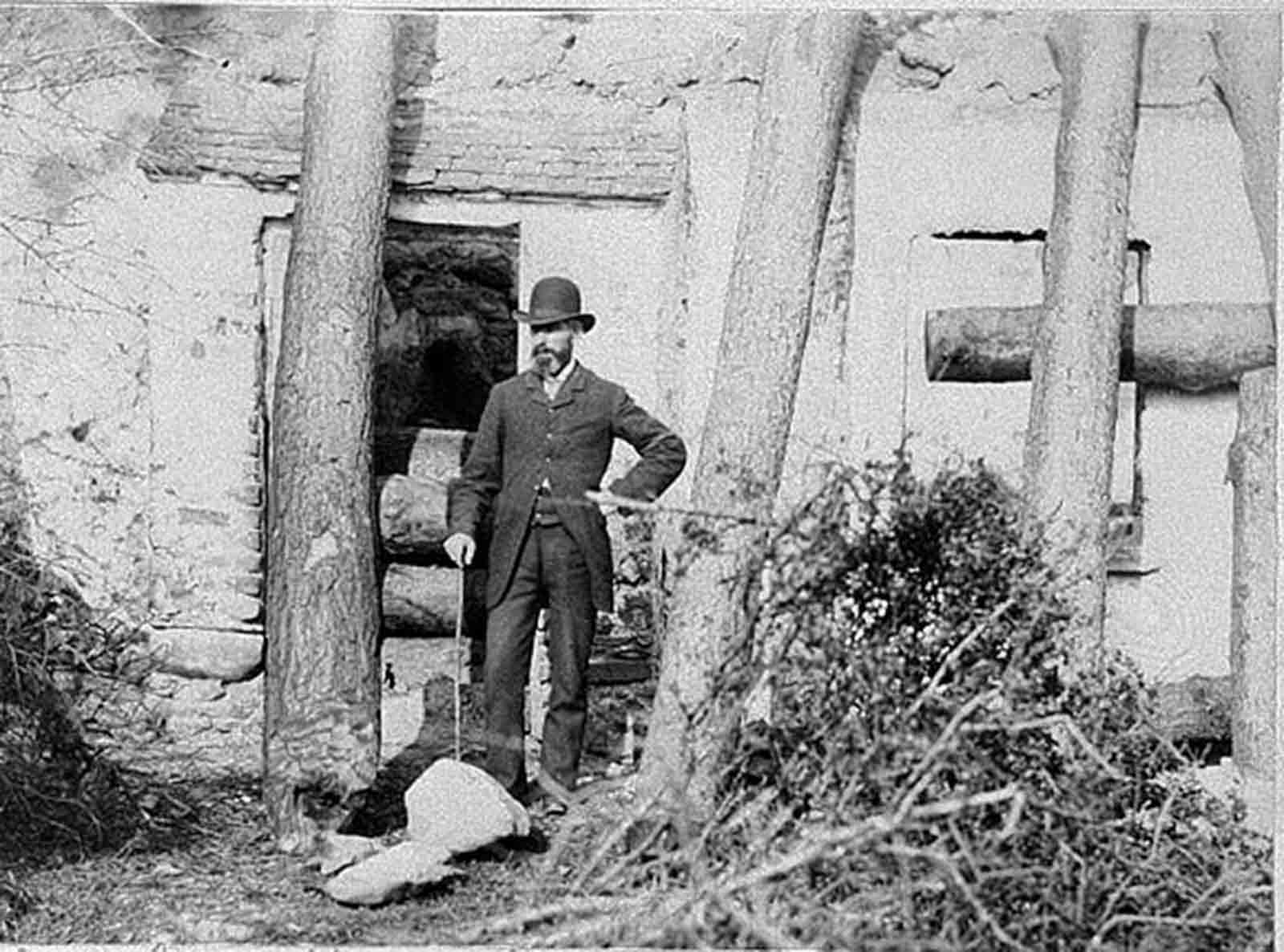

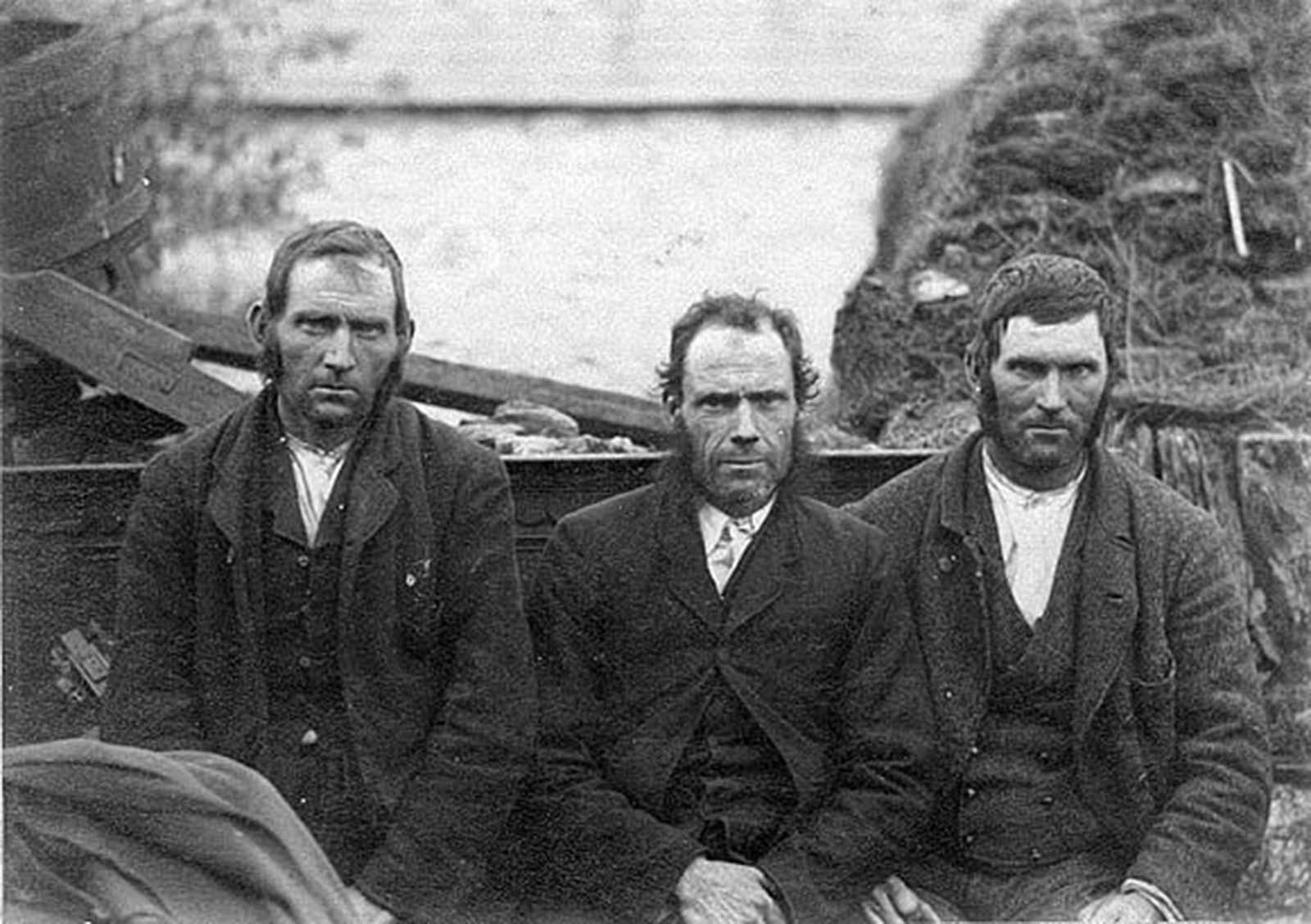

The movement emerged during a severe agricultural depression caused by crop failures and a sluggish market for farm produce. Economic conditions for farmers took a serious downturn in 1877, recovered partially in 1878, but deteriorated again in 1879. Unrest began on a small scale in late 1878, grew slowly during the early months of 1879, and then accelerated in the spring of 1879 when a series of public meetings were held in the western province of Connaught. With the help of nationalist politicians, a “Land League” was formed in County Mayo in August 1879 and the “Irish National Land League” was founded in October. The agitation remained strongest in western regions, but at times it raged in almost all parts of the country, with the notable exception of the northeast. Tenant farmers resisted evictions, refused to pay their normal rents, and demanded that parliament make extensive alterations to the laws governing ownership and occupation of agricultural land in Ireland. The inequality of late 19th century land ownership is best articulated by the statistic that 800 families owned 50% of the land. Ireland’s overall population stood at around 5,000,000 in 1879, the vast majority of whom lived in the country as tenants on small plots rented from the landlords. The poor tenant farmers were often exploited by landlords, especially by “absentee landlords,” those landlords who lived outside of Ireland, who raised rents without regard to what the farmer could pay or what the land could bear. From the summer of 1879 the land league and its supporters carried out various activities aimed at preventing evictions while advancing the cause of tenants. This ranged from protests at sales of leases of evicted tenants, protest meetings some of which were 10,000′s strong to more militant riots and even assassinations. The league itself did not officially sanction any illegal activity however some organisers did advocate more militant methods. Perhaps the most famous and successful tactic of the league was the Boycott. Initially called social ostracism, boycotting saw landlords or those who opposed the league shunned by their community. They were hissed everywhere they went, while no one would speak to them. People also refused to work for ostracised individuals or sell them produce. In 1881 the massive wave of repression saw nearly all land league leaders both radical and conservative imprisoned, however this only served to make the situation in Ireland worse, with violent incidents soaring in late 1881. At the same time however the British Prime Minister Gladstone introduced the 1881 land act which granted a certain amount of rights to tenants. The 1881 land act allowed many tenants to get serious rent reductions and this undermined the need for tenants to engage in activism around rent and tenancy rights. Although the power of landlords would only truly be broken until the 20th century, the 1881 Land Act made life almost intolerable for landlords in Ireland. This Act and a further amendment in 1887 which widened the scope of the bill meant it would only be a matter of time before the landlordism in rural Ireland was brought to an end. William Henry Hurlbert, account of Tully eviction, 1888: Two constables were burned by the red-hot pikes, the gun of another was broken to pieces by a huge stone, and a fourth was slightly wounded by a fork. Frank O’Halloran’s account of his family’s eviction, 1887: On the morning of the eviction we were up at the break of day and laid our plans, each to defend a certain point and none to waiver, whatever might come. We boiled plenty of water and meal, and, when all was ready, we kept a look-out for the bailiffs and the rest of them. At this time I was only home a few months from America, and during my absence, I may add, I did not learn to love Irish landlordism or English rule. The Clare Journal, June 6, 1887: What was calculated upon as one of the most formidable items in the program of defense and defiance was the letting loose of a hive of bees, but these took flight by the chimney. One of McNamara’s sons, who endeavored to keep them down, was very severely stung. Frank O’Halloran’s account of his family’s eviction, 1887: I got a big pole: there was a policeman at the top of the ladder; I put it to his chest, pushed him into an upright position. The policeman behind him pressed him on, while the crowd yelled, wild with delight. I shoved harder and he fell to the ground, amidst deafening cheers and shouts. Others pressed on, to meet the same fate.

(Photo credit: National Library of Ireland / An Introduction to ‘The Land War 1879-1882’ – Irish Origins). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe