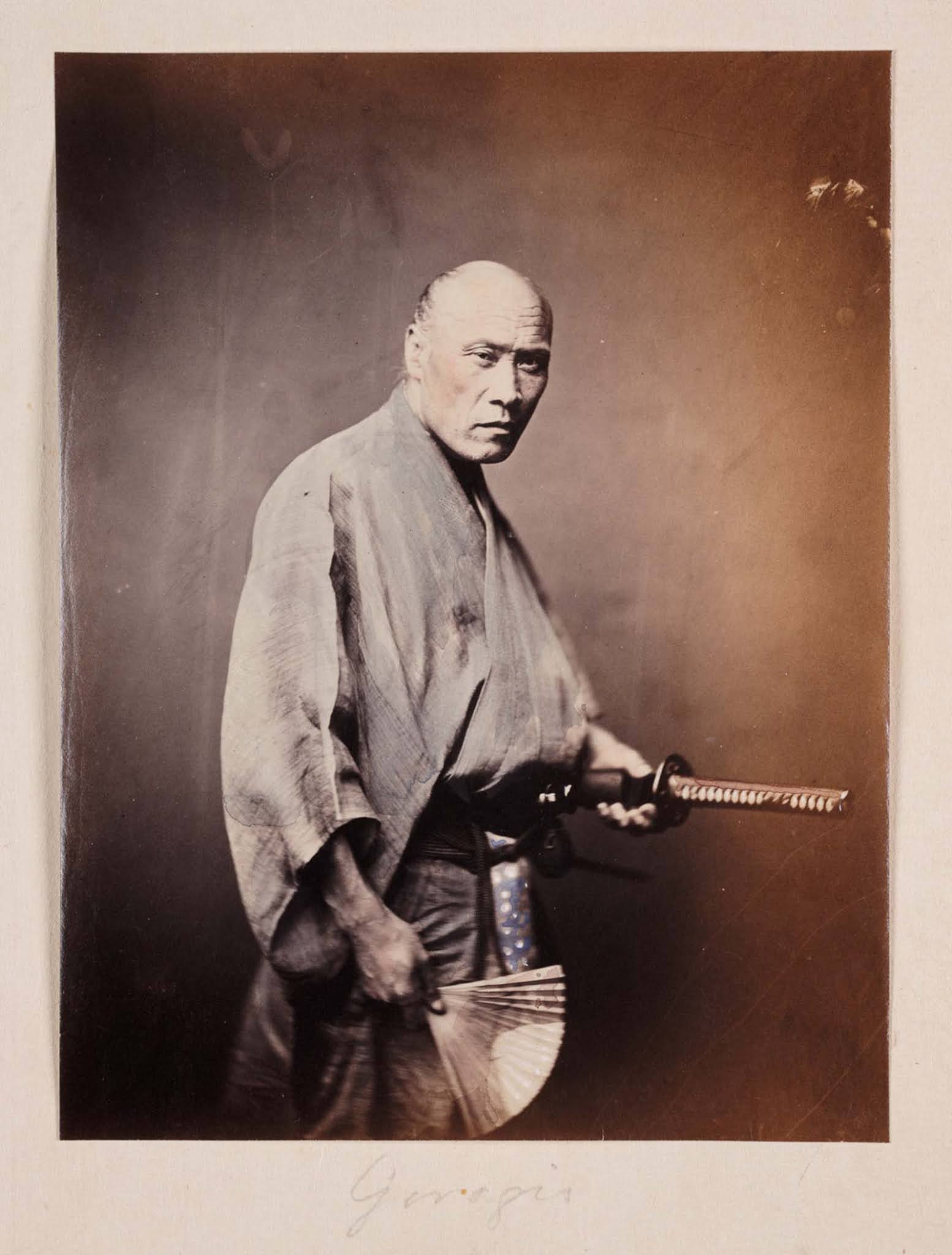

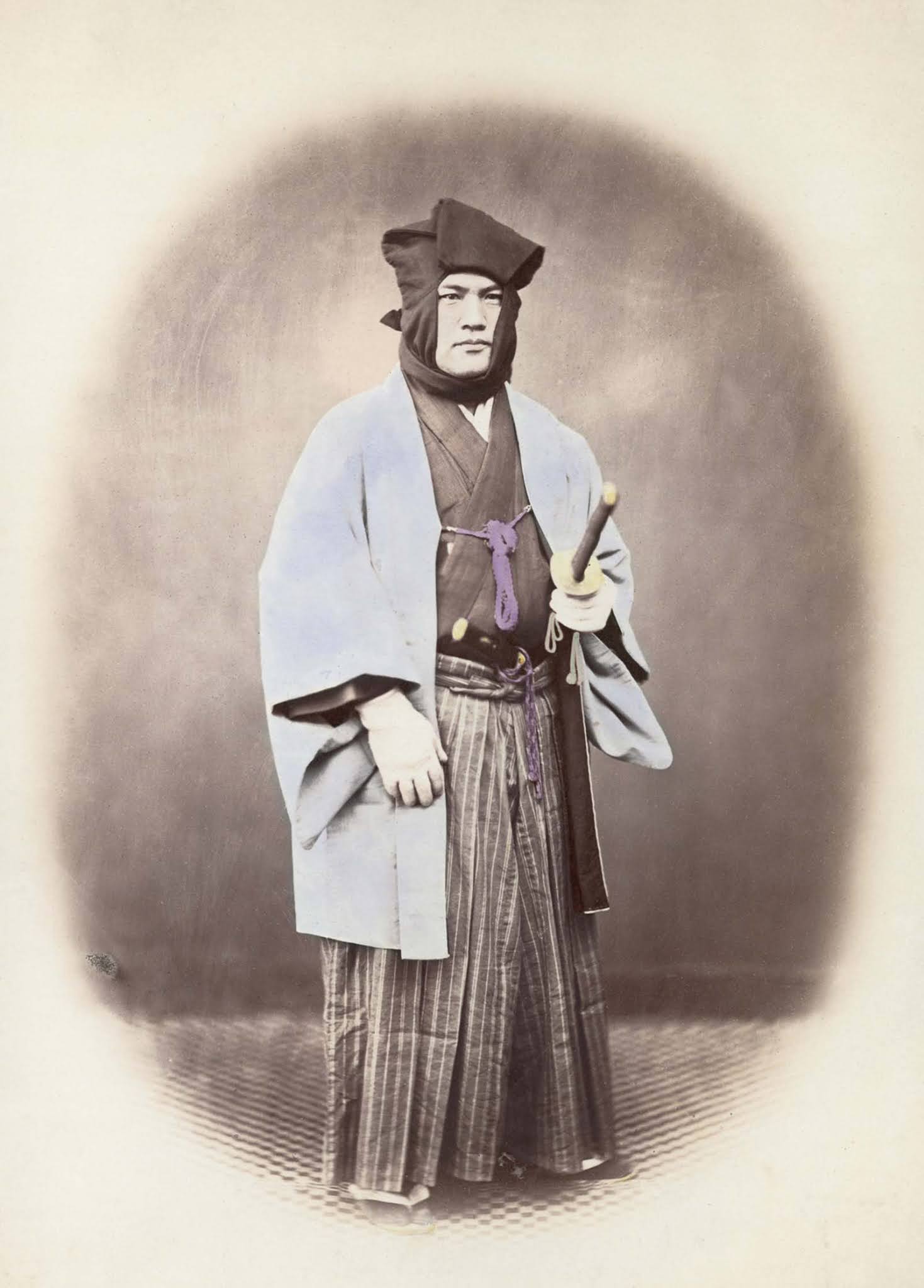

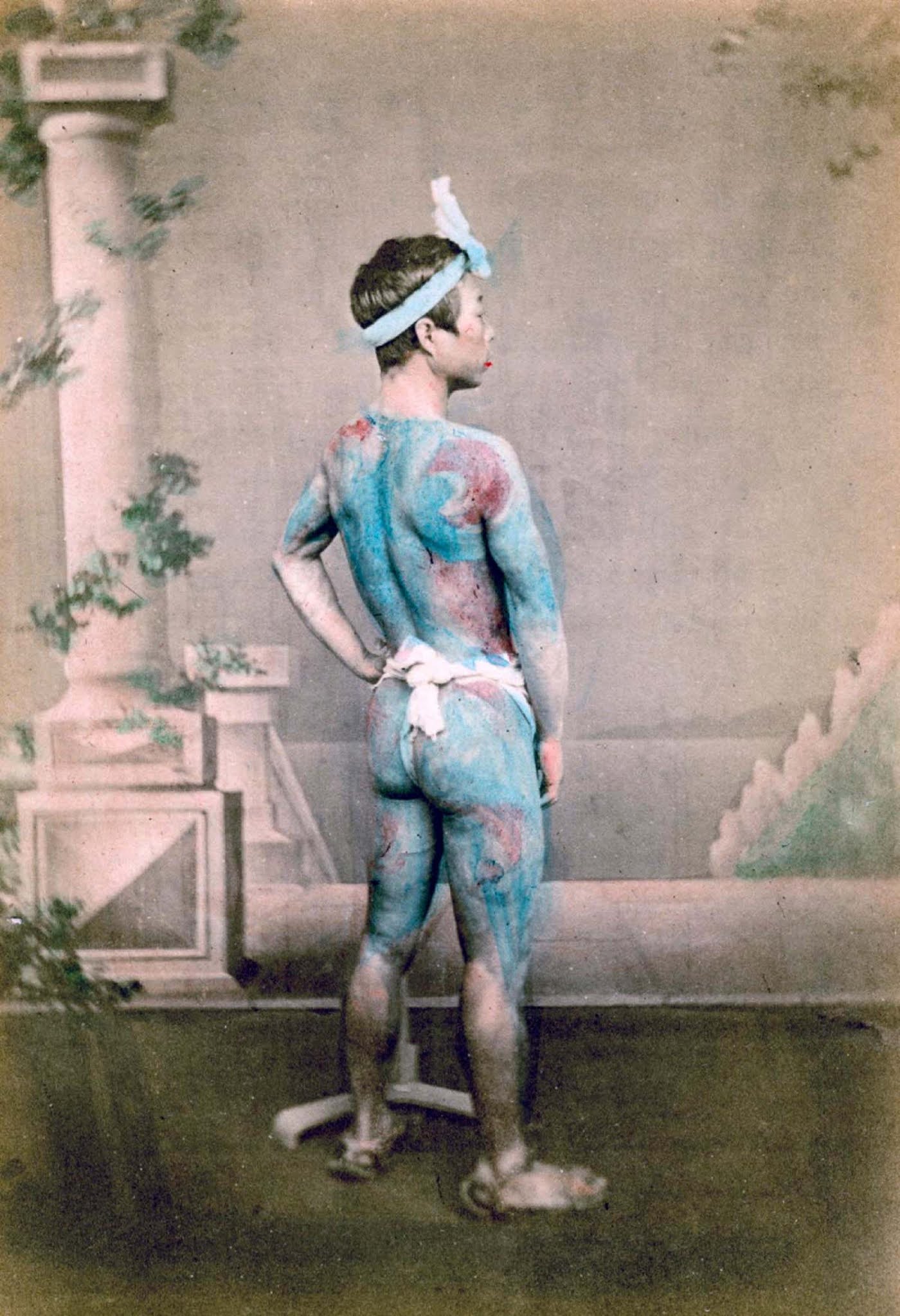

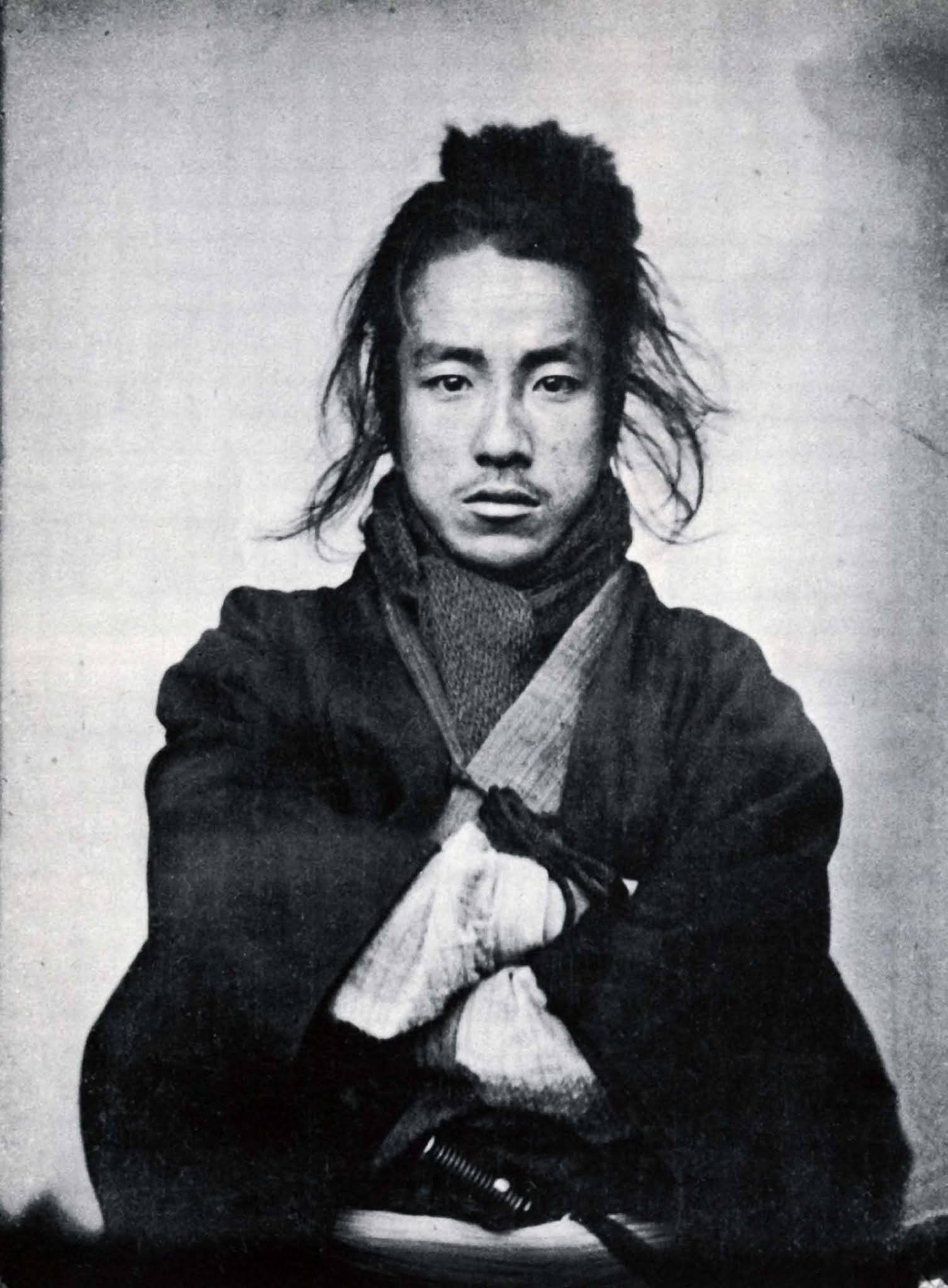

The word bushi means “man of arms.’ Another document from the Heian period, listing various professions, includes bushi along with other specialists such as men of letters, doctors, singers, dancers, and others. As numerous studies have pointed out, they were neither landowners nor armed farmers; from the beginning, they were professional warriors. They were the well-paid retainers of the daimyo (the great feudal landholders). They had high prestige and special privileges such as wearing two swords. Samurai warriors live by Bushido, a code of behavior that covers nearly every area of life. Bushido demanded that a samurai show absolute loyalty and obedience to his lord. He must gladly face danger, even death, in the performance of his duties. The Hagakure, an eighteenth-century collection of writings on Bushido, proclaims, “The way of the Samurai is death… When a samurai is constantly prepared for death, he… may unerringly devote his life to the service of his lord.” The samurai who failed his lord suffered a dishonor worse than death. There was only one way to erase the disgrace. The samurai must commit seppuku, sometimes called hara-kiri, or “belly sitting.” In this horribly painful form of suicide, the dishonored samurai used a short sword to cut open his belly and release his spirit. Bushido demanded that samurai live pure, simple lives. They must show dignity, respect, and quiet confidence. The ideal samurai knew the proper way to walk, bow, hold his chopsticks, remove enemy heads in battle, and display them afterward. He knew the value of honesty. “Never say a single word of falsehood or even half of it,” samurai warlord Hojo Soun counseled in the 1400s. Soun also advised his samurai followers to study poetry, reading, and writing. “Hold literary skills in your left hand,” he wrote, “martial [warlike] skills in your right. This is the law from ancient times.” Samurai had arranged marriages, which were arranged by a go-between of the same or higher rank. While for those samurai in the upper ranks this was a necessity (as most had few opportunities to meet women), this was a formality for lower-ranked samurai. Most samurai married women from a samurai family, but for lower-ranked samurai, marriages with commoners were permitted. In these marriages, a dowry was brought by the woman and was used to set up the couple’s new household. A samurai could take concubines, but their backgrounds were checked by higher-ranked samurai. In many cases, taking a concubine was akin to a marriage. Kidnapping a concubine, although common in fiction, would have been shameful, if not criminal. During the Tokugawa Era (1603-1868), many samurai began to be more bureaucrats rather than warriors. Without any warfare or conflict for over a hundred years, the samurai were beginning to lose their original purpose of fighting. Eventually, Emperor Meiji removed many of the privileges the samurai enjoyed during all these centuries. They were dismissed as Japan’s only army and were replaced by a Western-styled, conscription-based army. Samurai lost many of their social standings and lost the sole right to carry swords or attack commoners for disrespect. Many samurai did end up joining the army or, as the few literate people in Japan, become public officials, or study abroad and become academic elite. However, after the end of the Meiji Restoration, the samurai had officially fallen and no longer exclusively controlled the military and political scene of Japan.

(Photo credit: Universal History Archive /UIG / Getty Images / Japan in the Days of the Samurai / The Samurai: A Military History / Samurai An Illustrated History). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe