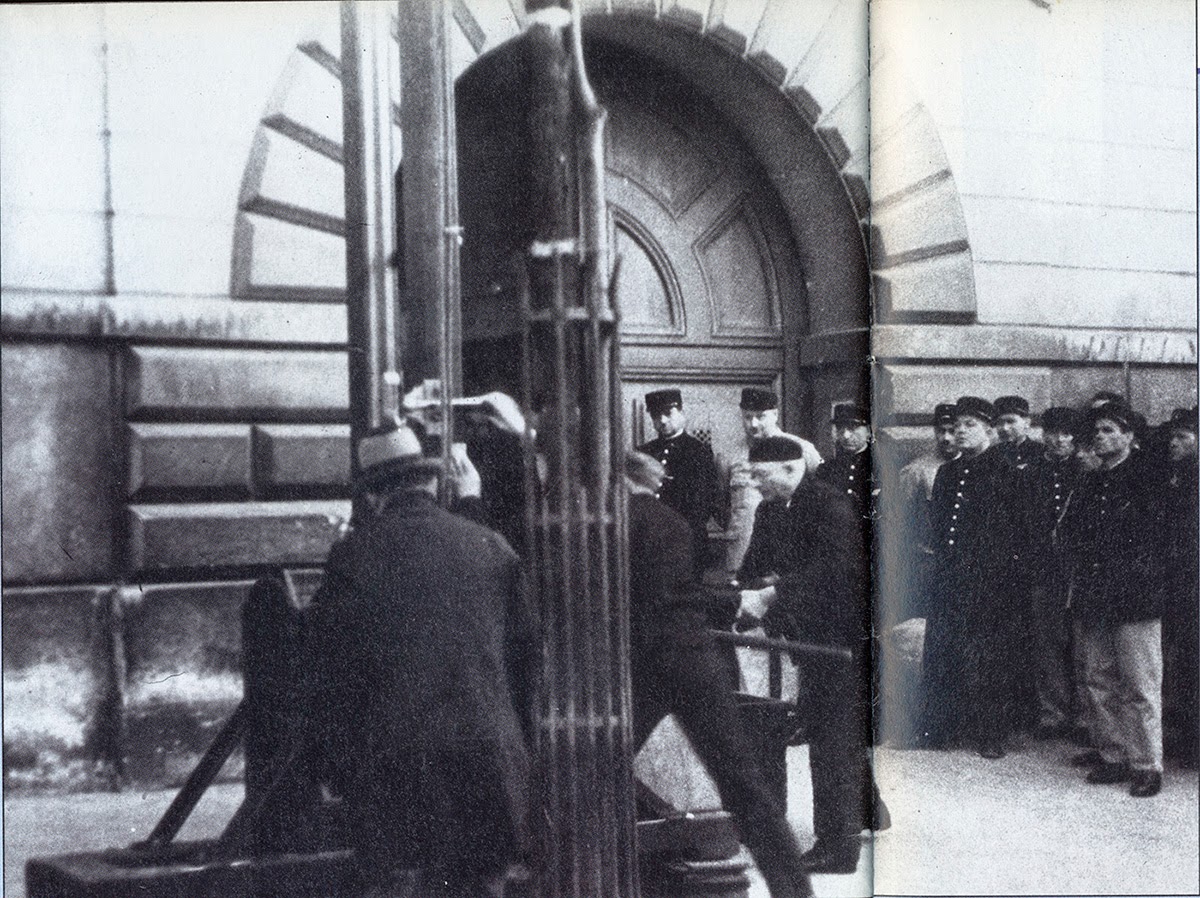

Beginning with the botched kidnapping of an American tourist, the inspiring dancer Jean de Koven, Eugène Weidmann murdered two women and four men in the Paris area in 1937. His other victims included a woman lured by the false offer of a position as a governess; a chauffeur; a publicity agent; a real estate broker; and a man Weidmann had met as an inmate in a German prison. On the surface, his crimes seemed in most cases to have had a profit motive, but they generally brought him very small winnings. Born in Frankfurt-am-Main in 1908, Weidmann early showed himself to be an incorrigible criminal. He had been sent to a juvenile detention facility and then served prison terms for theft and burglary in Canada and Germany prior to his arrival in Paris in 1937. After a sensational and much-covered trial, Weidmann was sentenced to death. On the morning of June 17, 1939, Weidmann was taken out in front of the Prison Saint-Pierre, where a guillotine and a clamoring, whistling crowd awaited him. Among the attendees was a future acting legend, Christopher Lee, then 17 years old. Weidmann was placed into the guillotine, and France’s chief executioner Jules-Henri Desfourneaux let the blade fall without delay. Rather than react with solemn observance, the crowd behaved rowdily, using handkerchiefs to dab up Weidmann’s blood as souvenirs. Paris-Soir denounced the crowd as “disgusting”, “unruly”, “jostling, clamoring, whistling”. The unruly crowd delayed the execution beyond the usual twilight hour of dawn, enabling clear photographs and one short film to be taken. After the event, the authorities finally came to believe that “far from serving as a deterrent and having salutary effects on the crowds” the public execution “promoted baser instincts of human nature and encouraged general rowdiness and bad behavior”. The “hysterical behavior” by spectators was so scandalous that French president Albert Lebrun immediately banned all future public executions. The guillotine was the only mean of execution that the French republic had ever known, the device was in service from 1792 to 1977. For almost 200 years the guillotine executed tens of thousands of culprits (or not) without ever failing to deliver a quick and painless death. While it is easy to see the guillotine as barbaric, it is actually a lot less gruesome than it looks. Capital punishment was very common in pre-revolutionary France. For nobles, the typical method of execution was beheading; for commoners, it was usually hanging, but less common and crueler sentences were also practiced. When Dr. Joseph-Ignace Guillotin proposed the new method of execution to the National Assembly, it was meant to be more humane than previous capital punishments and also to be an equal method of death for all criminals regardless of rank. Compared to many forms of capital punishment practiced to this day, the guillotine remains one of the best if we are judging based on pain and “cleanness”. In fact, the guillotine was developed with the idea of creating the most humane way to execute people. The condemned don’t feel pain, death is almost instantaneous and there are very few ways for things to be botched. The head of the victim remains alive for about 10-13 seconds, depending on the glucose and blood levels in his brain at the time. However, the head is believed to be more than likely knocked unconscious by the force of the blow and blood loss. The guillotine was heavily used during the Reign of Terror (June 1793 to July 1794) with an estimated death toll range between 15,000 and 40,000 people. British actor Christopher Lee was present at this last public execution. He was 17. Convicted murderer Hamida Djandoubi became the last person to meet his end by the “National Razor” after he was executed by the guillotine in 1977. Still, the machine’s 189-year reign only officially came to an end in September 1981, when France abolished capital punishment for good. Guillotine operators were national celebrities. Executioners won a great deal of notoriety during the French Revolution when they were closely judged on how quickly and precisely they could orchestrate multiple beheadings. The job was often a family business. (Photo credit: France National Archives). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe