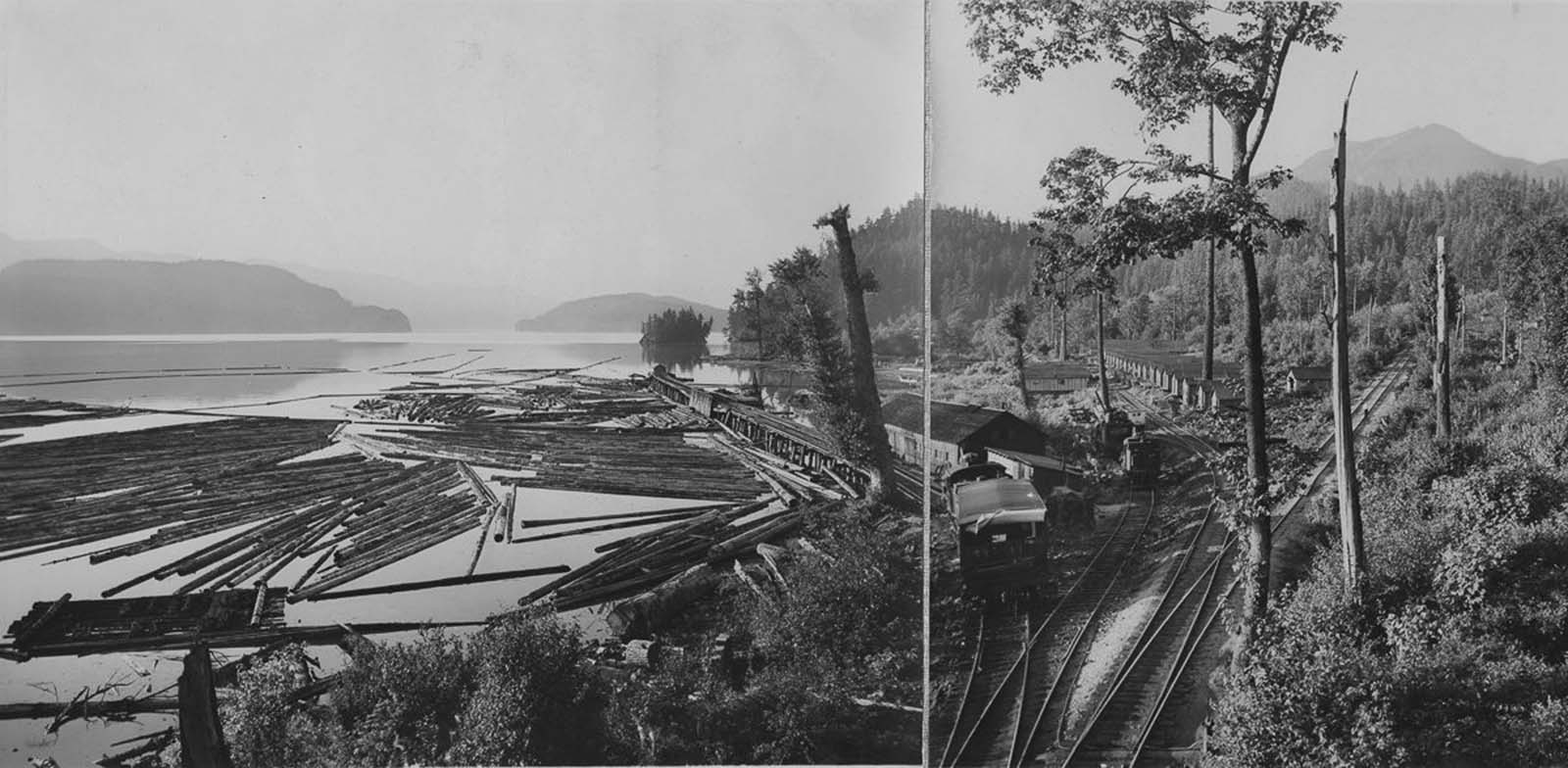

The completion of the Panama Canal in 1914 marked the third phase of the history of the trade, for it opened to the industry the communities of the Atlantic, especially the seaboard of the United States and the important United Kingdom market. Despite the rugged and difficult terrain, the abundance of towering cedar and Douglas Fir trees made the area an attractive source for ships’ masts and other lumber products. Whereas in the colder eastern forests felled trees could be skidded down snowy roads, in the west skid roads had to be built out of wood. Trees were transported from the mountains down to the water by oxen, trucks, skids, flumes, and railroads spanning canyons on freshly built trestle bridges. By 1930, half of Canada’s annual timber harvest came from British Columbia. The pattern of the lumber trade changed again after 1940. War-time shipping difficulties, followed by a seemingly permanent dollar shortage in the sterling area largely diminished the importance of the United Kingdom market a sustained period of prosperity in the United States, however, facilitated a shift of trade lines from the Old World to the New. The change was accelerated and consolidated by the rise of giant American cellulose corporations which invested heavily In British Columbia forest lands and production plants and integrated them into vast international complexes of industries whose main market is the pulp, lumber, and cellulose-hungry industries of the United States. For the longest time, lumberjacks toiled from dawn to dusk, six days per week, and lived tightly packed in shanties (or bunkhouses) whose odor — a mix of smoke, sweat, and drying garments — was as distasteful as the bedbugs they supported. Strict rules often governed many of the bush camps (or “shanties”); many were alcohol-free and for the longest time talking during meals was strictly forbidden. The food was usually top-notch, and enormous amounts of it were served. Lumberjacks burned roughly 7,000 calories per day, which explains their voracious appetites. In addition, cooks sometimes only allowed 10 to 15 minutes for loggers to eat, accounting for the gravity often governing mealtimes. (Photo credit: University of British Columbia Library). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe