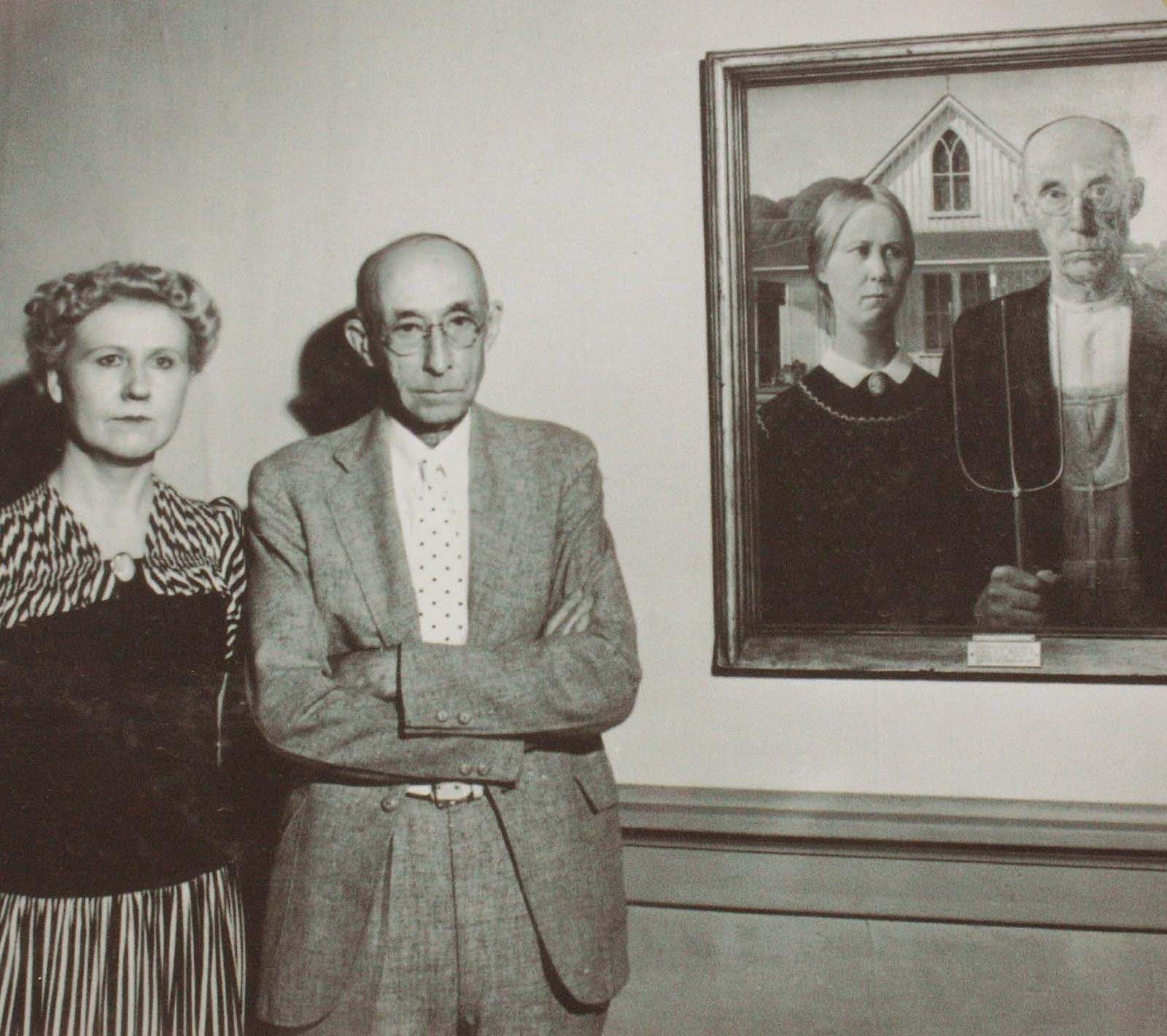

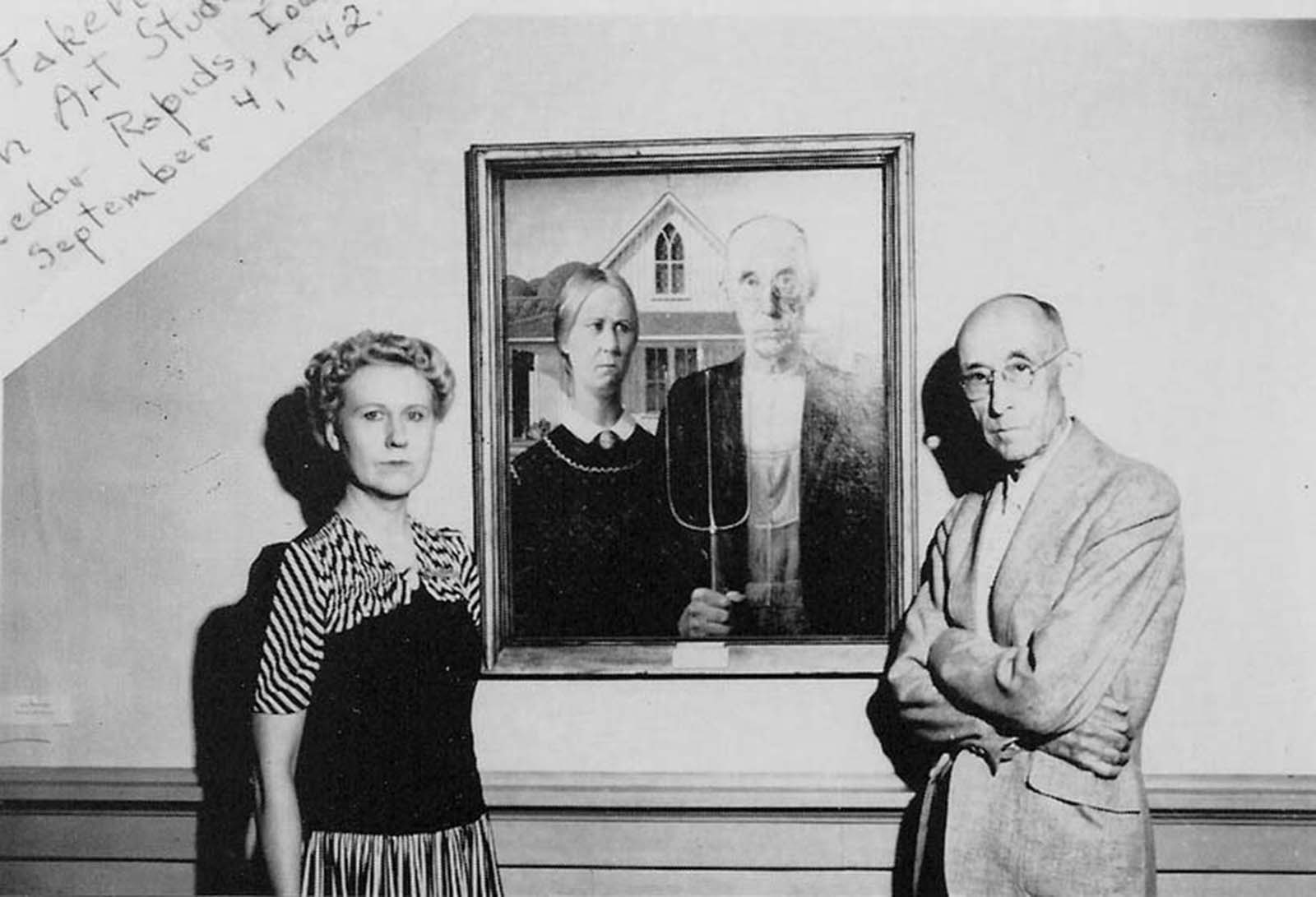

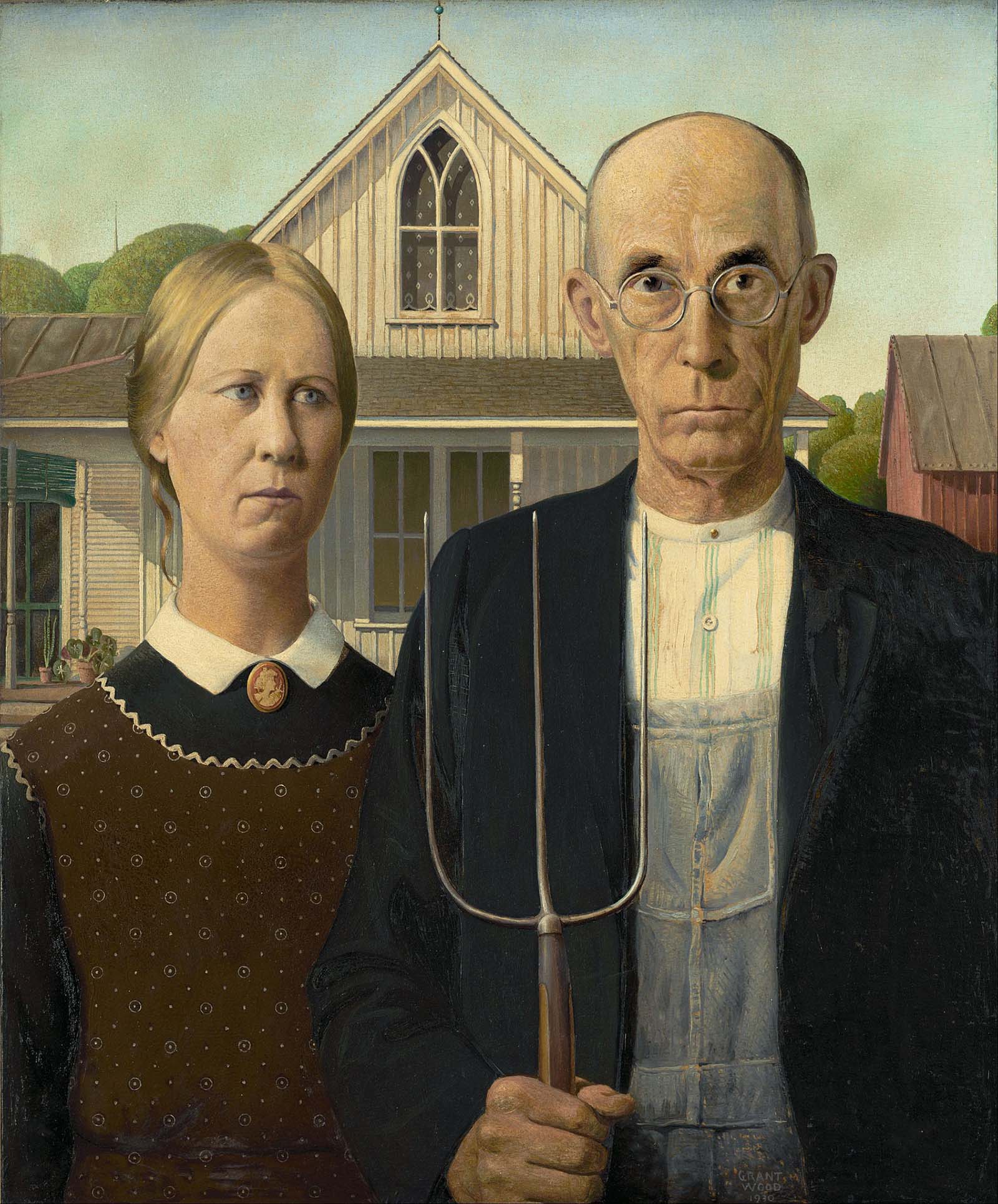

The woman is dressed in a colonial print apron evoking 20th-century rural Americana while the man is adorned in overalls covered by a suit jacket and carries a pitchfork. The plants on the porch of the house are mother-in-law’s tongue and beefsteak begonia It’s one of the most famous U.S. paintings of its generation and the models who posed were Nan Wood Graham, the painter’s sister, and Dr. Byron McKeeby, a dentist. The painting is named for the house’s architectural style. According to the Art Institute of Chicago, the impetus for the painting came while Wood was visiting the small town of Eldon in his native Iowa. There he spotted a little wood farmhouse, with a single oversized window, made in a style called Carpenter Gothic. Wood’s earliest biographer, Darrell Garwood, noted that Wood “thought it formed a borrowed pretentiousness, a structural absurdity, to put a Gothic-style window in such a flimsy frame house”. After obtaining permission from the house’s owners, Selma Jones-Johnston and her family, Wood made a sketch the next day in oil paint on paperboard from the front yard. This sketch depicted a steeper roof and a longer window with a more pronounced ogive than on the actual house – features which eventually adorned the final work. Wood decided to paint the house along with, in his words, “the kind of people [he] fancied should live in that house”. He recruited his sister, Nan (1899–1990), to be the model for the daughter, dressing her in a colonial print apron mimicking 20th-century rural Americana. The model for the father was the Wood family’s dentist, Dr. Byron McKeeby (1867–1950) from Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Nan told people that her brother had envisioned the pair as father and daughter, not husband and wife, which Wood himself confirmed in his letter to Mrs. Nellie Sudduth in 1941: “The prime lady with him is his grown-up daughter.” Elements of the painting stress the vertical that is associated with Gothic architecture. The upright, three-pronged pitchfork is echoed in the stitching of the man’s overalls and shirt, the Gothic pointed-arch window of the house under the steeped roof, and the structure of the man’s face. The pitchfork glistened silver with white highlights on grays and blacks, capturing the sunshine that angled down at forty-five degrees and cast a shadow under the gable and on the porch’s clapboards. Later, in response to complaints that “he didn’t know anything about pitchforks, since all of them have 4 prongs” — and to conjectures “that the prongs had deep religious or phallic significance” — he said that the pitchfork he painted really did have three prongs. The Art Institute of Chicago cleared up the controversy by explaining that it’s a hay fork, not a pitchfork. The three-tined forks are usually used for working with hay. Grant stretched out Graham and the doctor’s face in the picture so that no one would be able to recognize them. Another interesting fact is that none of the models posed together. Wood painted the house, his sister, and his dentist in separate sessions. American Gothic was submitted to the 1930 annual exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, where it won a bronze medal and a $300 prize. The Art Institute acquired the piece for its collection. From there, a picture of the prize-winning painting ran in the Chicago Evening Post, then in newspapers across the U.S., gaining fame and popularity with each printing. There was a backlash. Iowans were furious at their depiction as “pinched, grim-faced, puritanical Bible-thumpers”. Wood protested, saying that he had not painted a caricature of Iowans but a depiction of his appreciation, stating “I had to go to France to appreciate Iowa.” In a 1941 letter, Wood said that, “In general, I have found, the people who resent the painting are those who feel that they themselves resemble the portrayal.” American Gothic, often understood as a satirical comment on the midwestern character, quickly became one of America’s most famous paintings and is now firmly entrenched in the nation’s popular culture. Yet Wood intended it to be a positive statement about rural American values, an image of reassurance at a time of great dislocation and disillusionment. The man and woman, in their solid and well-crafted world, with all their strengths and weaknesses, represent survivors. Wood gave this confounding statement: “There is satire in it, but only as there is satire in any realistic statement. These are the types of people I have known all my life. I tried to characterize them truthfully—to make them more like themselves than they were in actual life.” Grant Wood died of pancreatic cancer in 1942, and his sister eventually moved to Northern California, where she became the caretaker of his legacy. She did, after all, owe him a debt. “Grant made a personality out of me,” she said. “I would have had a very drab life without the American Gothic.” (Photo credit: Grant Wood Archive / Wikimedia Commons / Wikipedia / American Gothic: A Life of America’s Most Famous Painting). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe