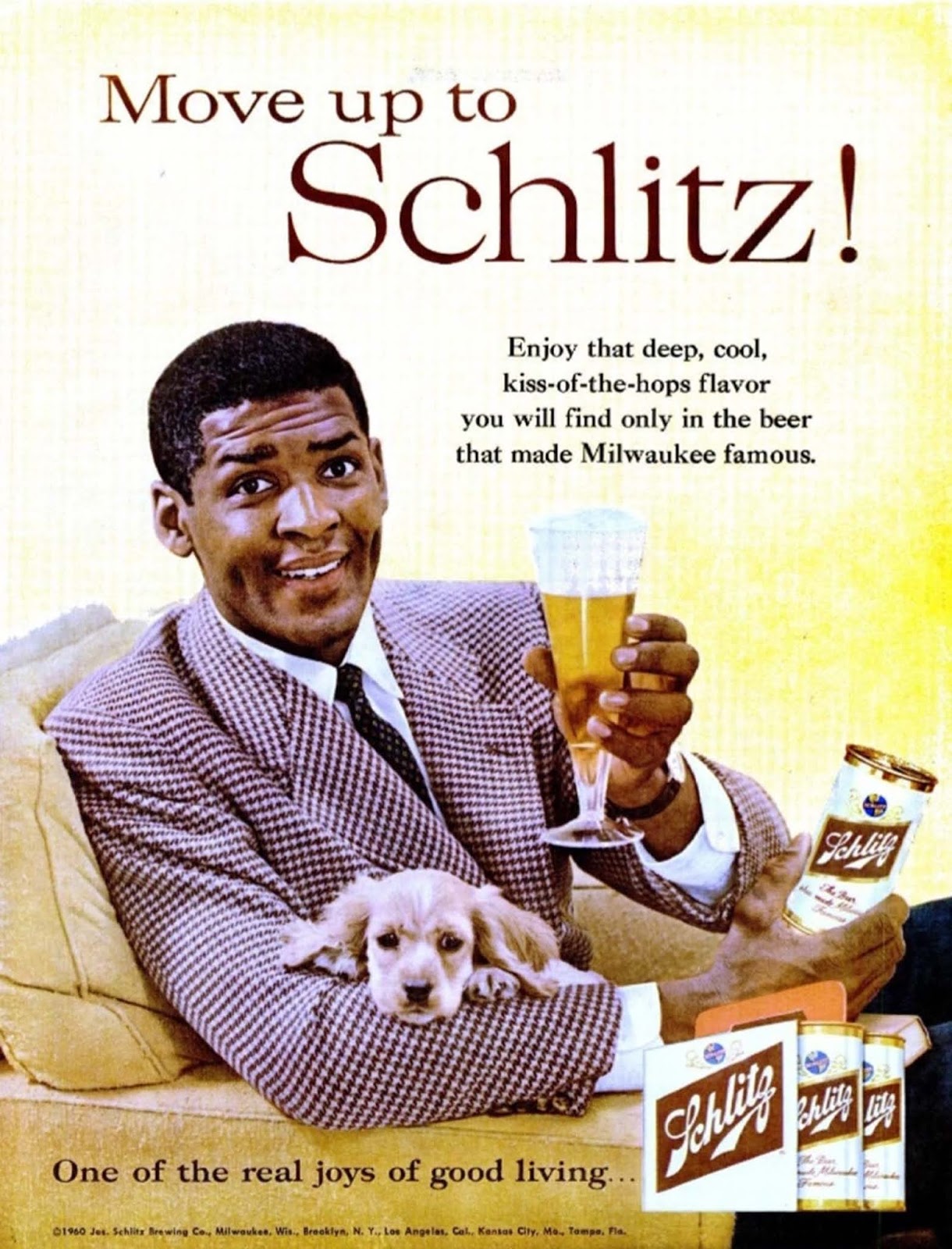

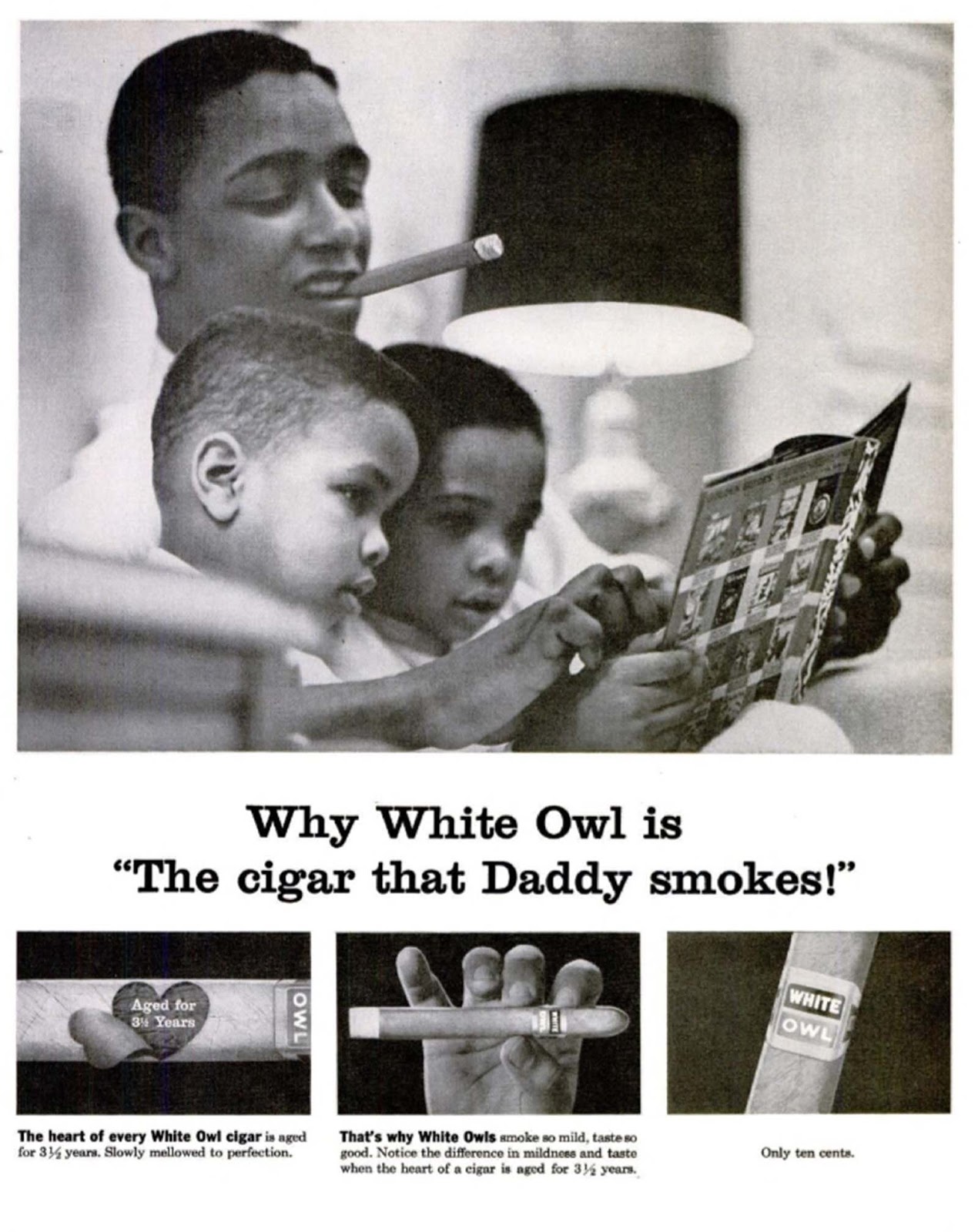

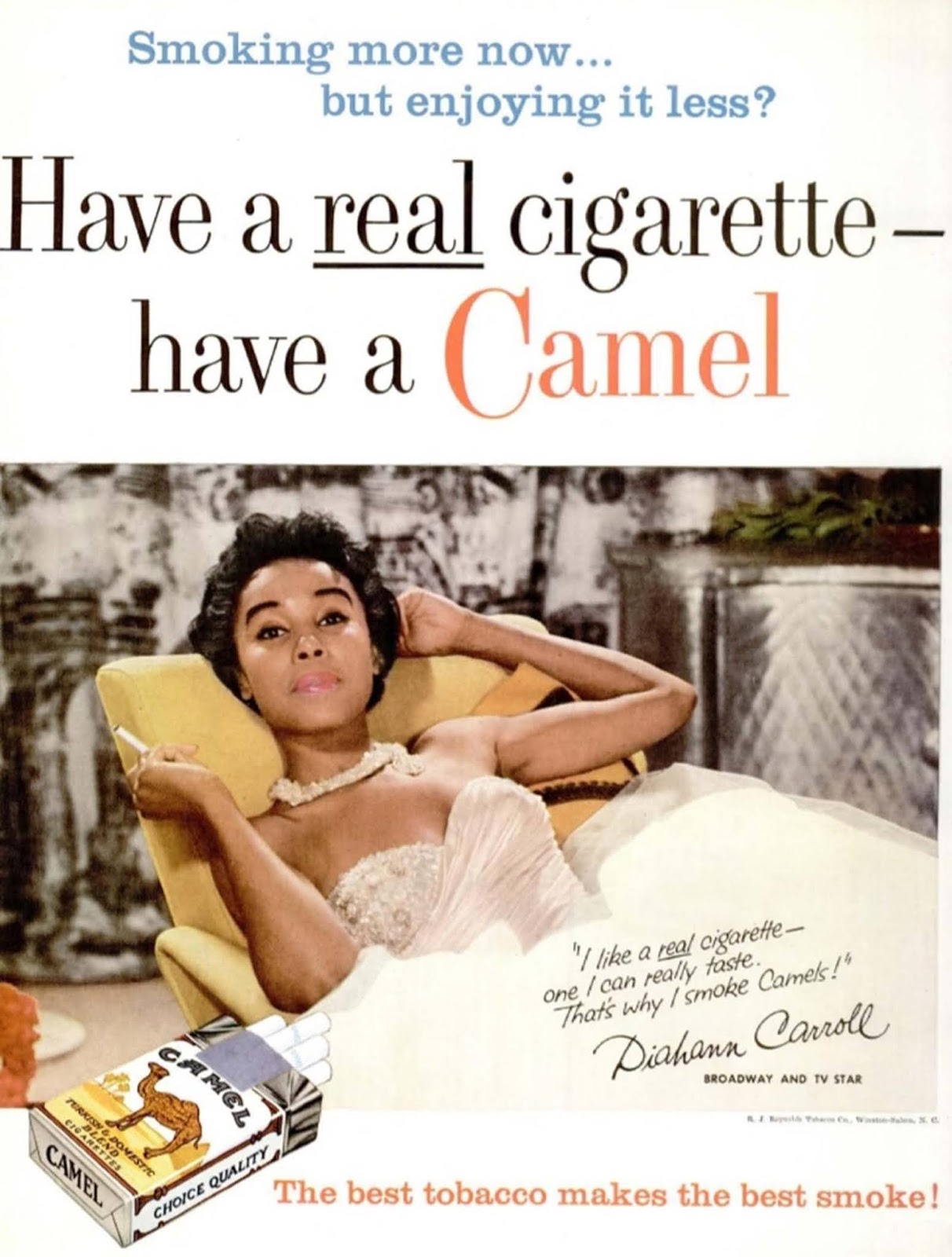

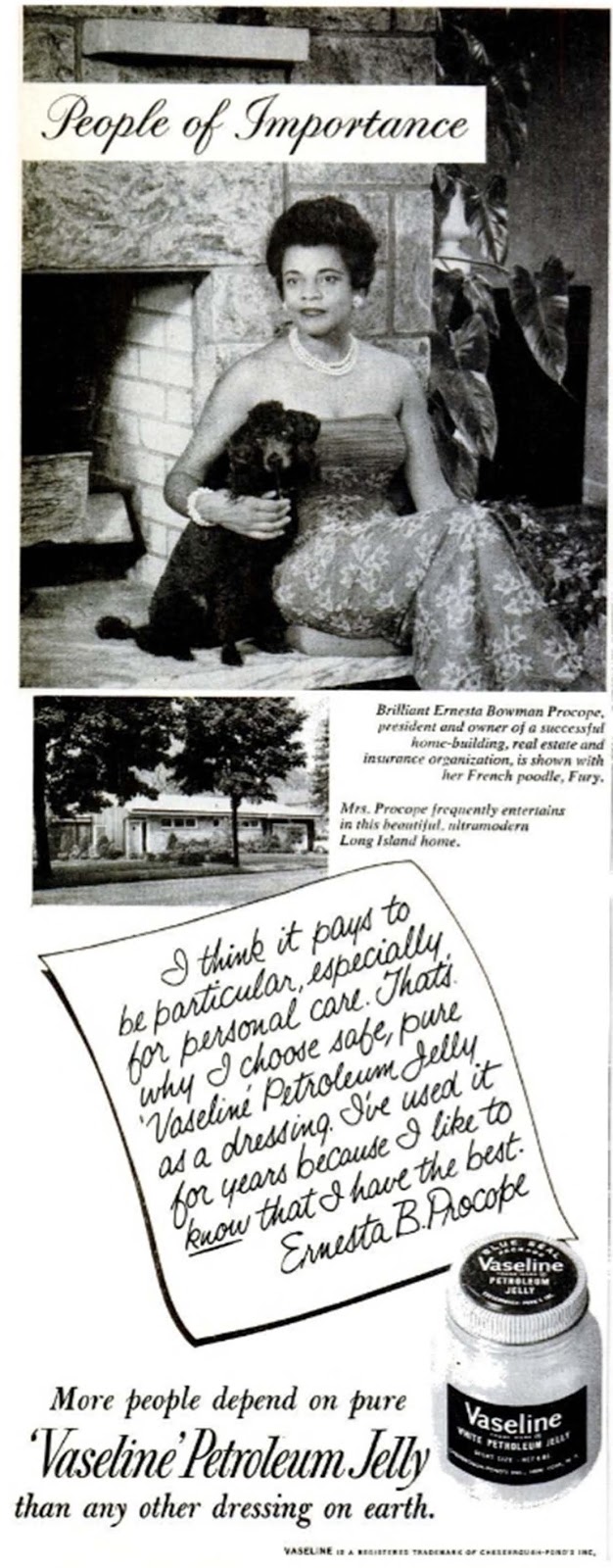

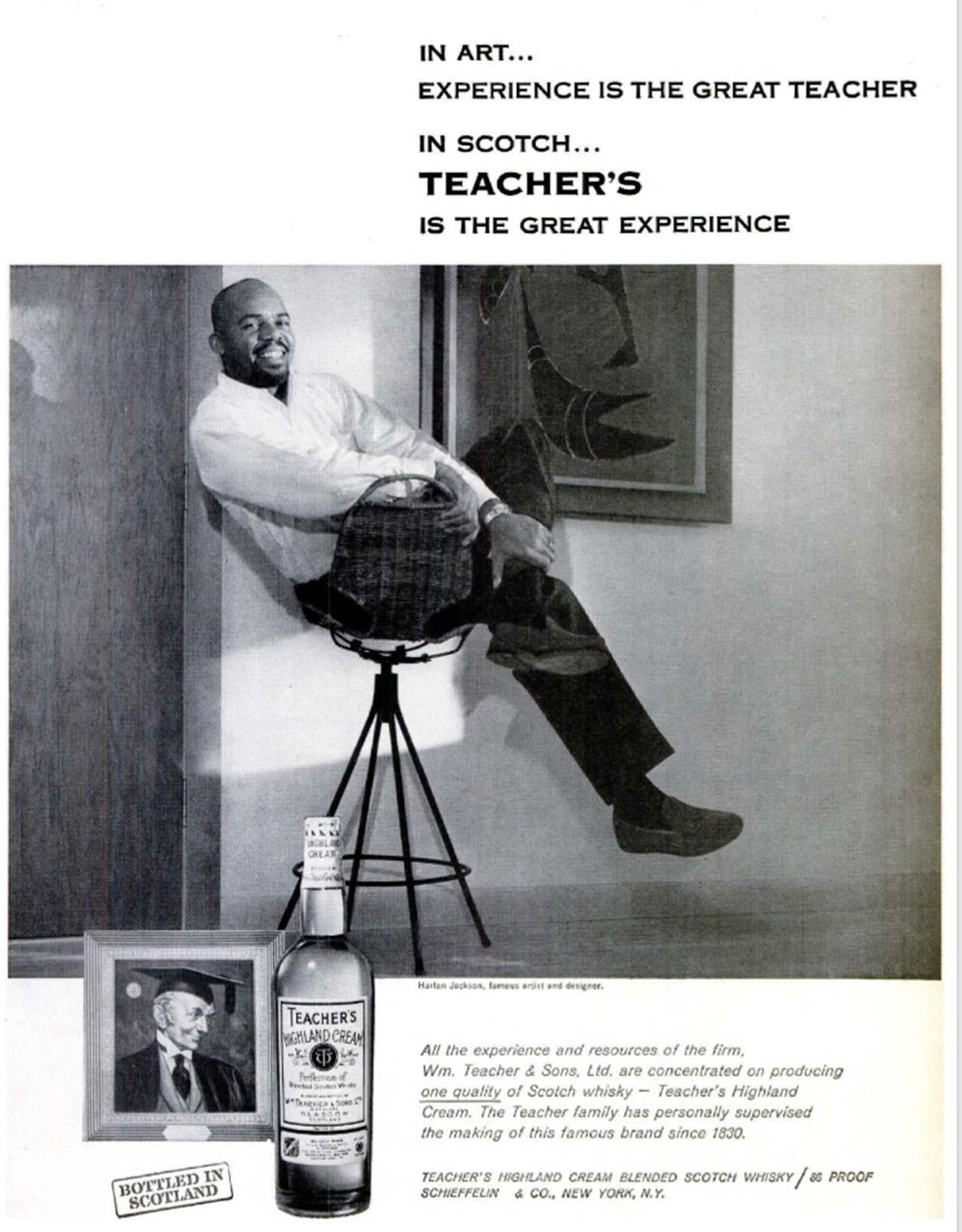

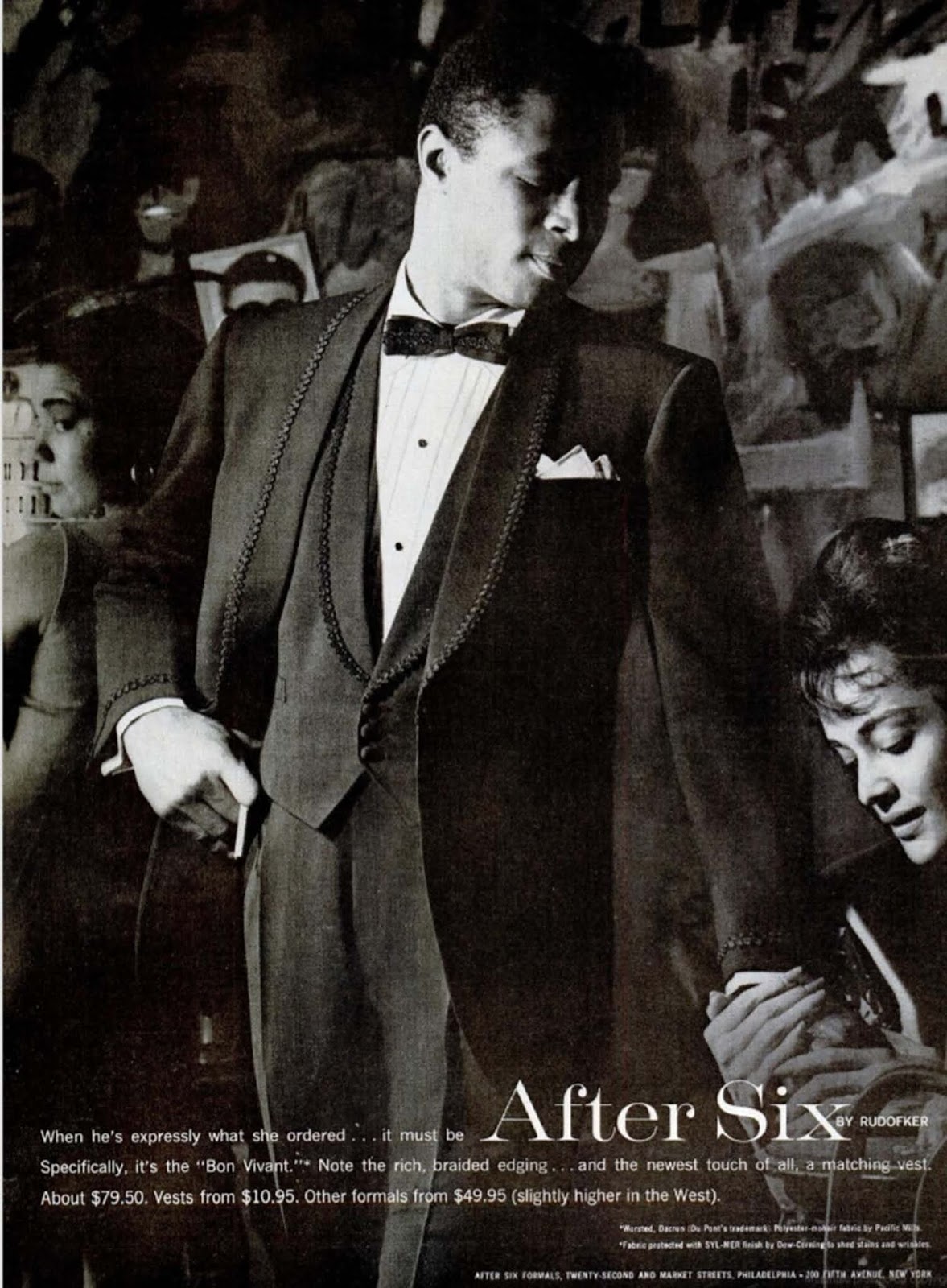

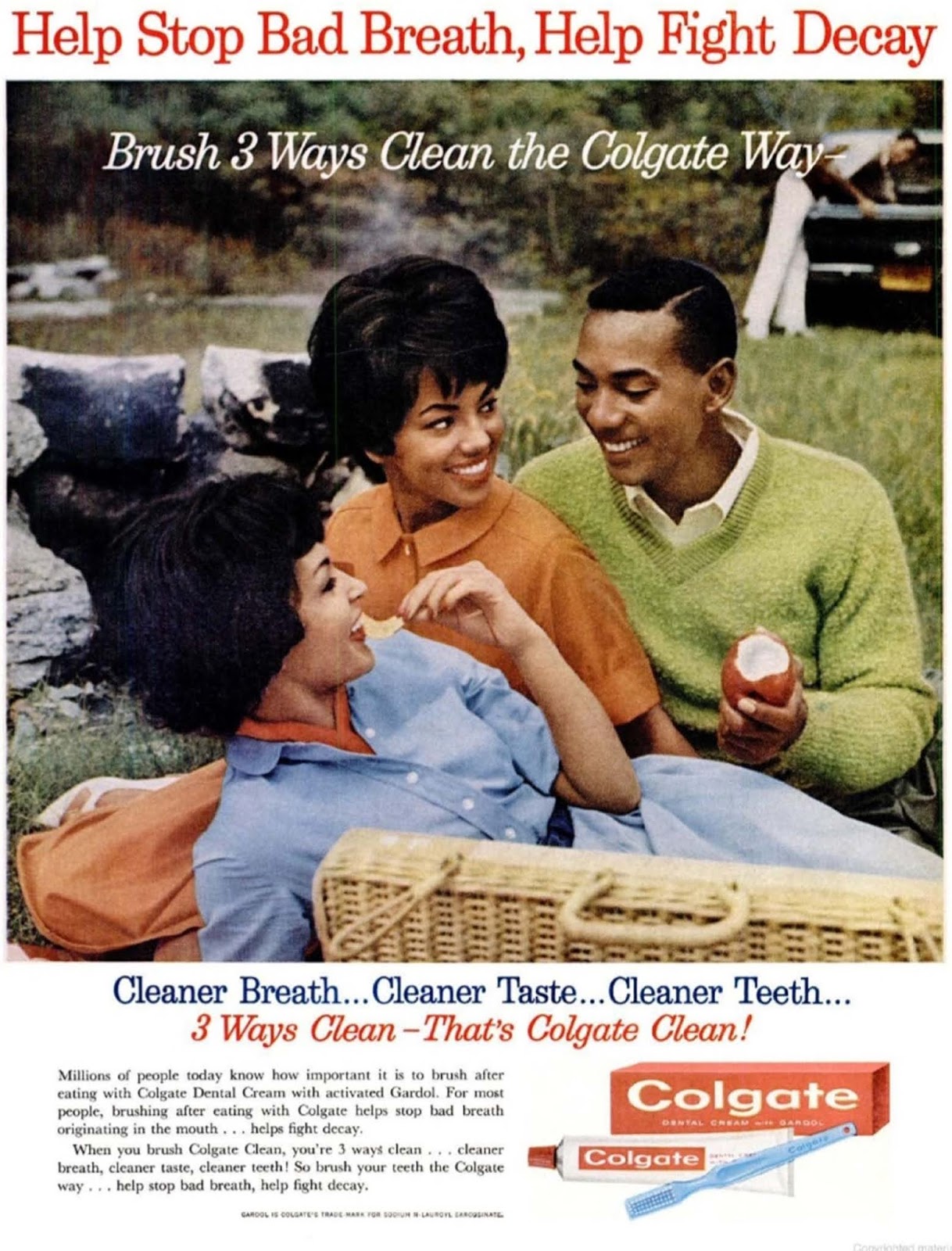

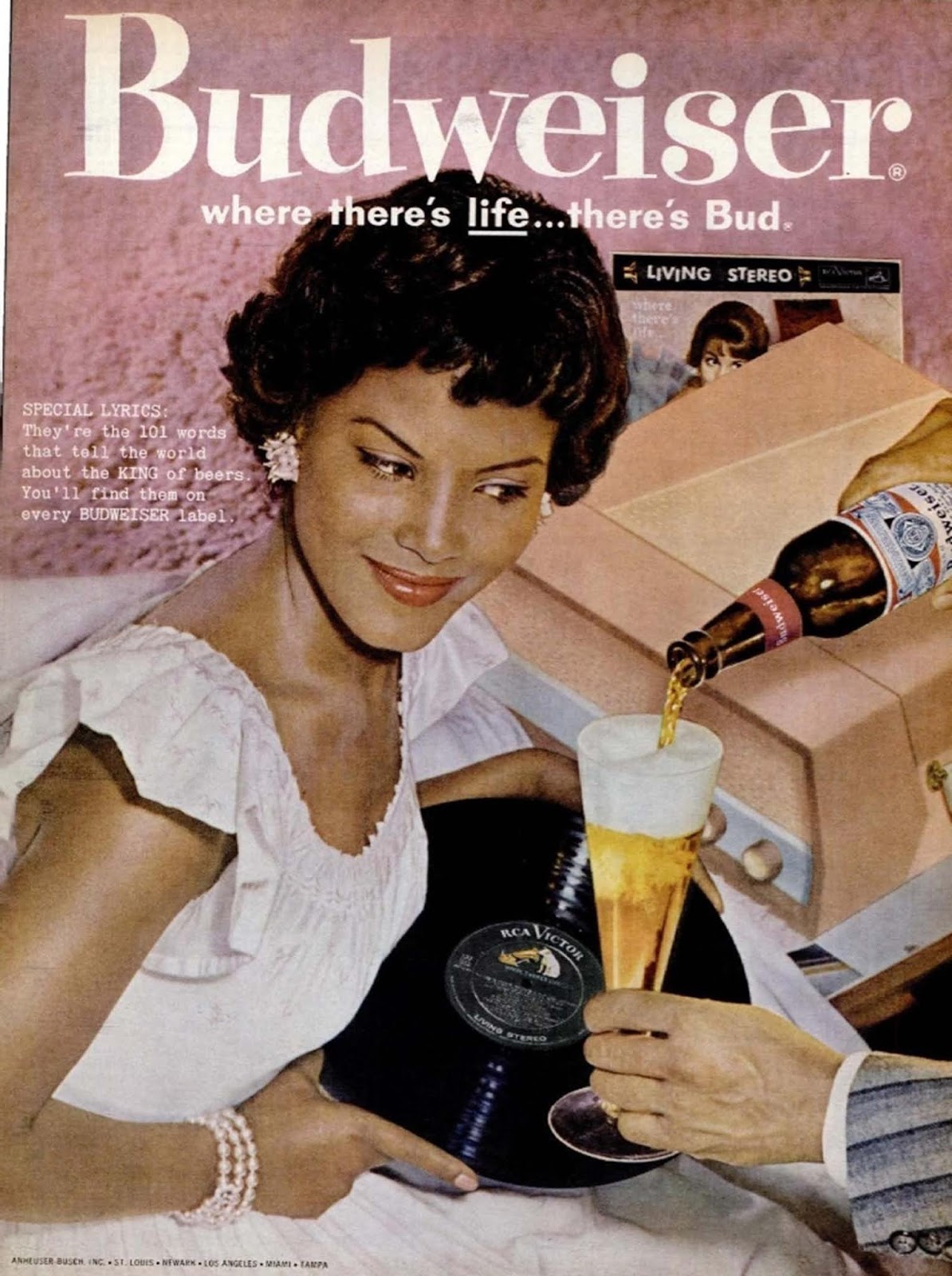

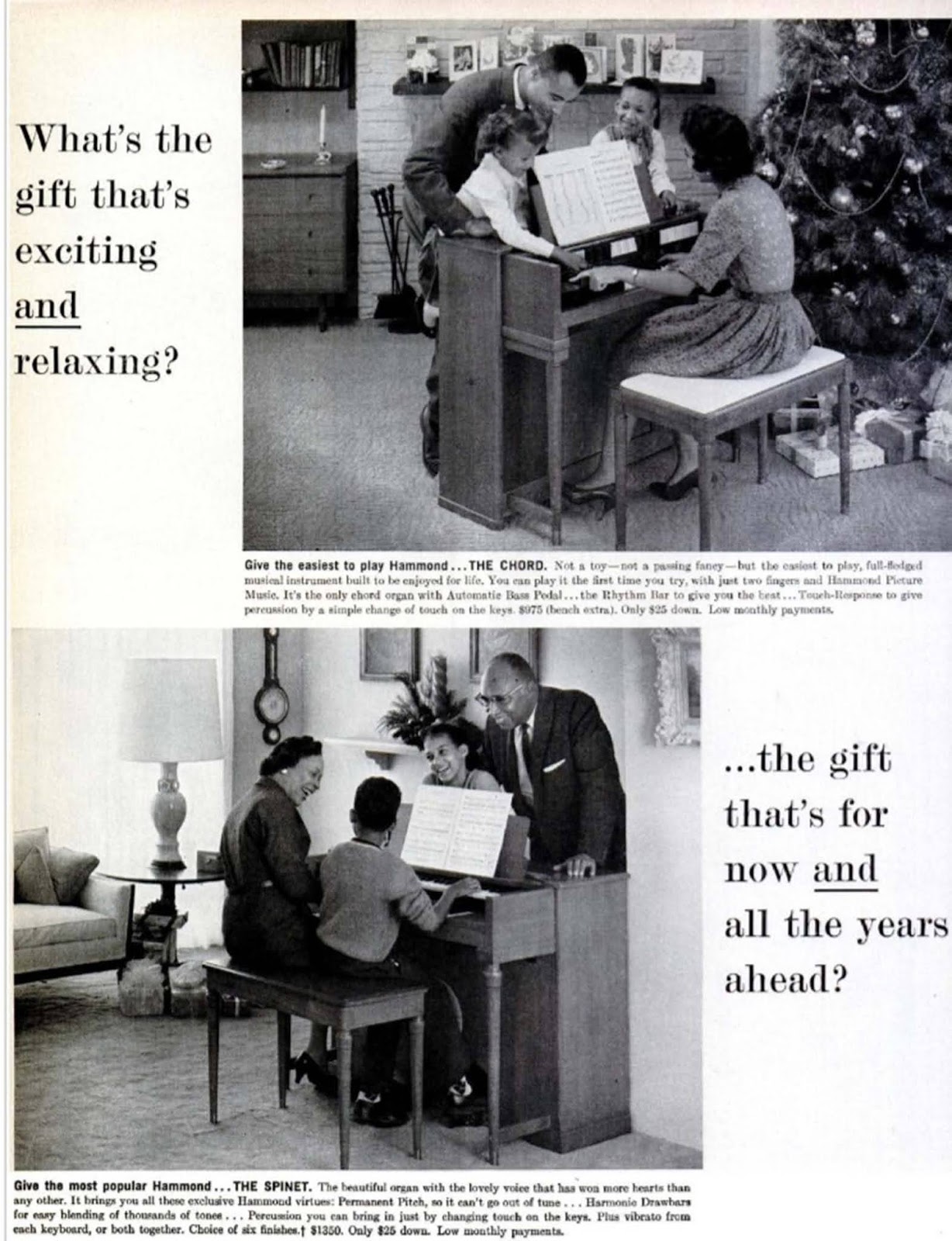

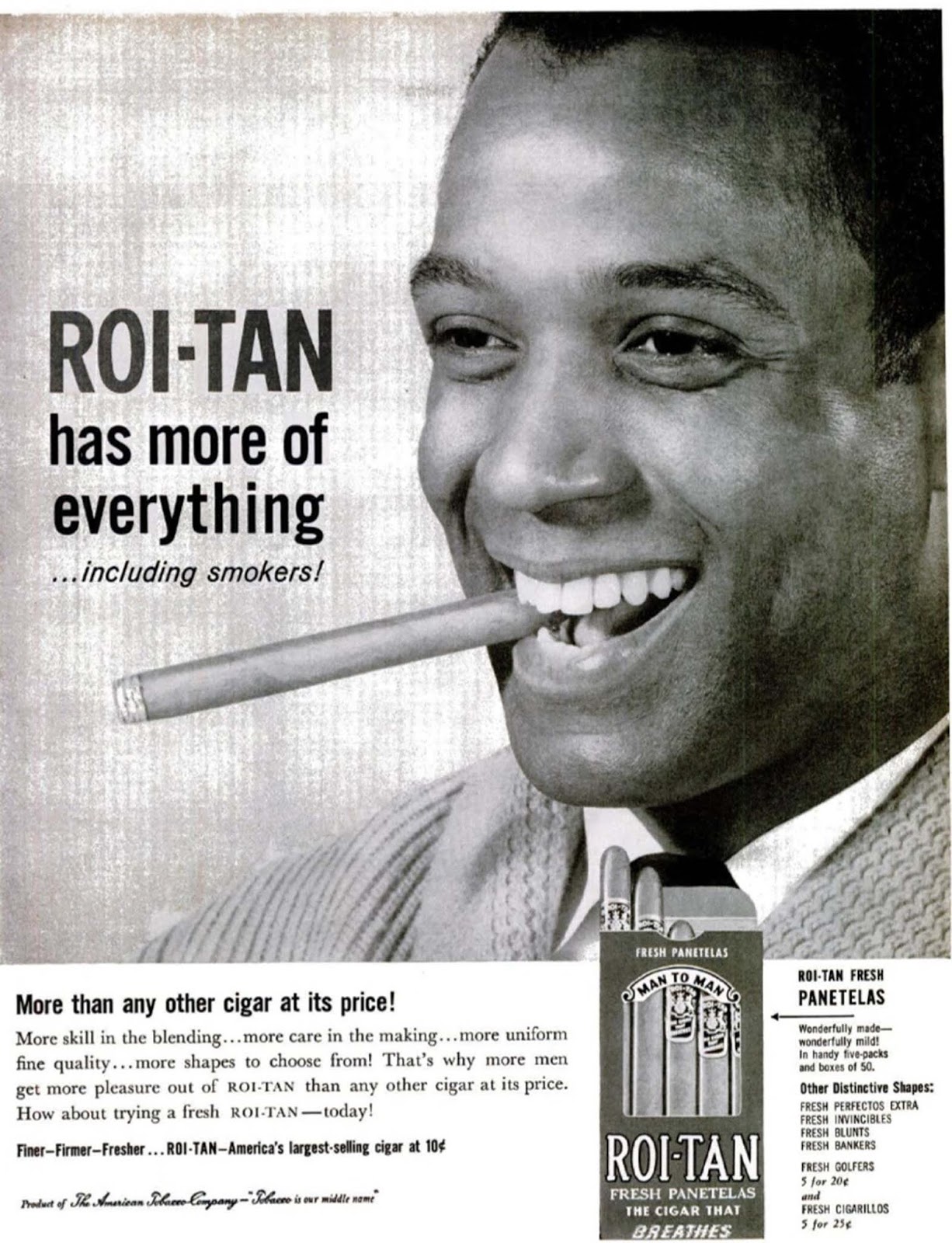

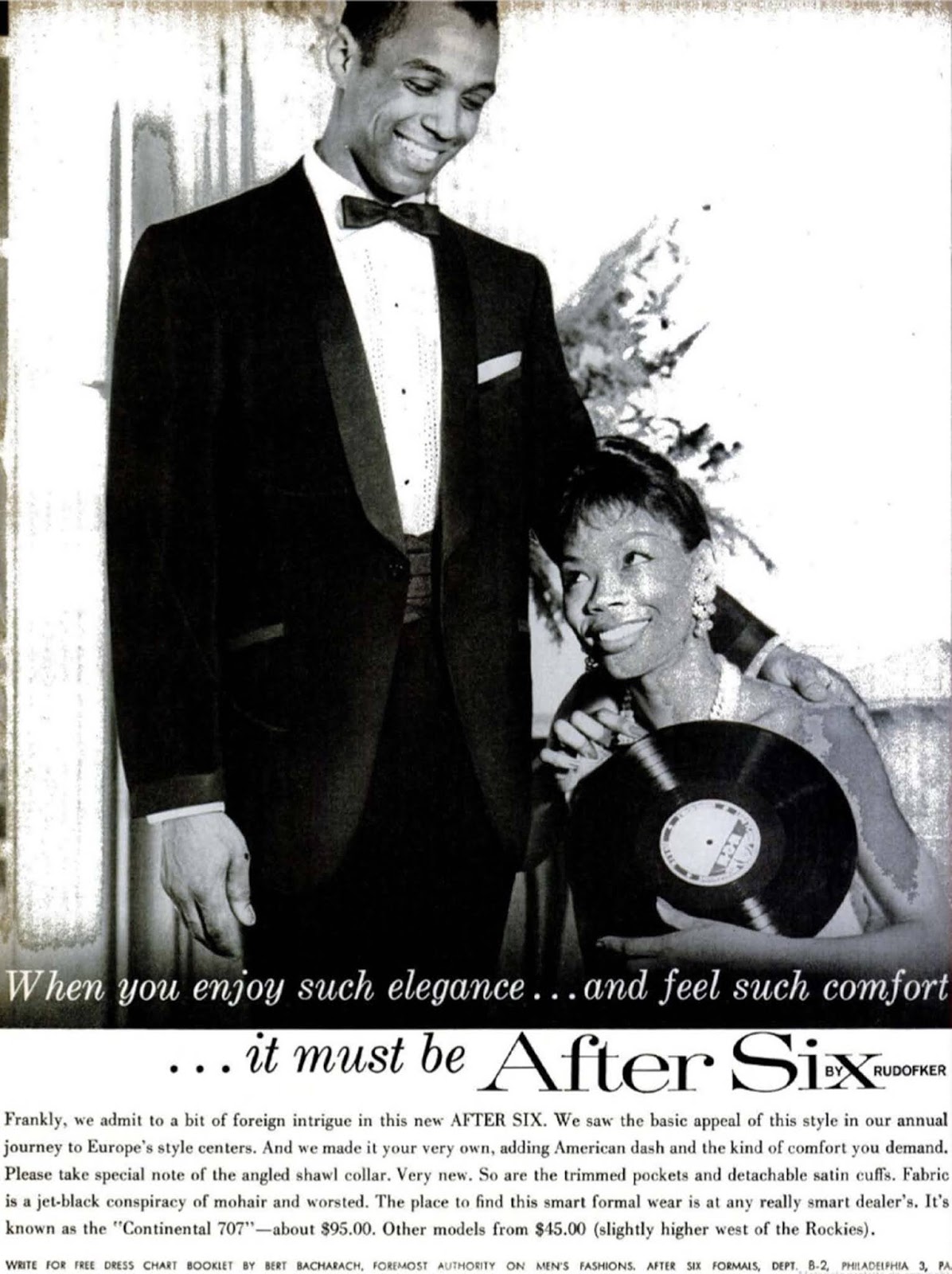

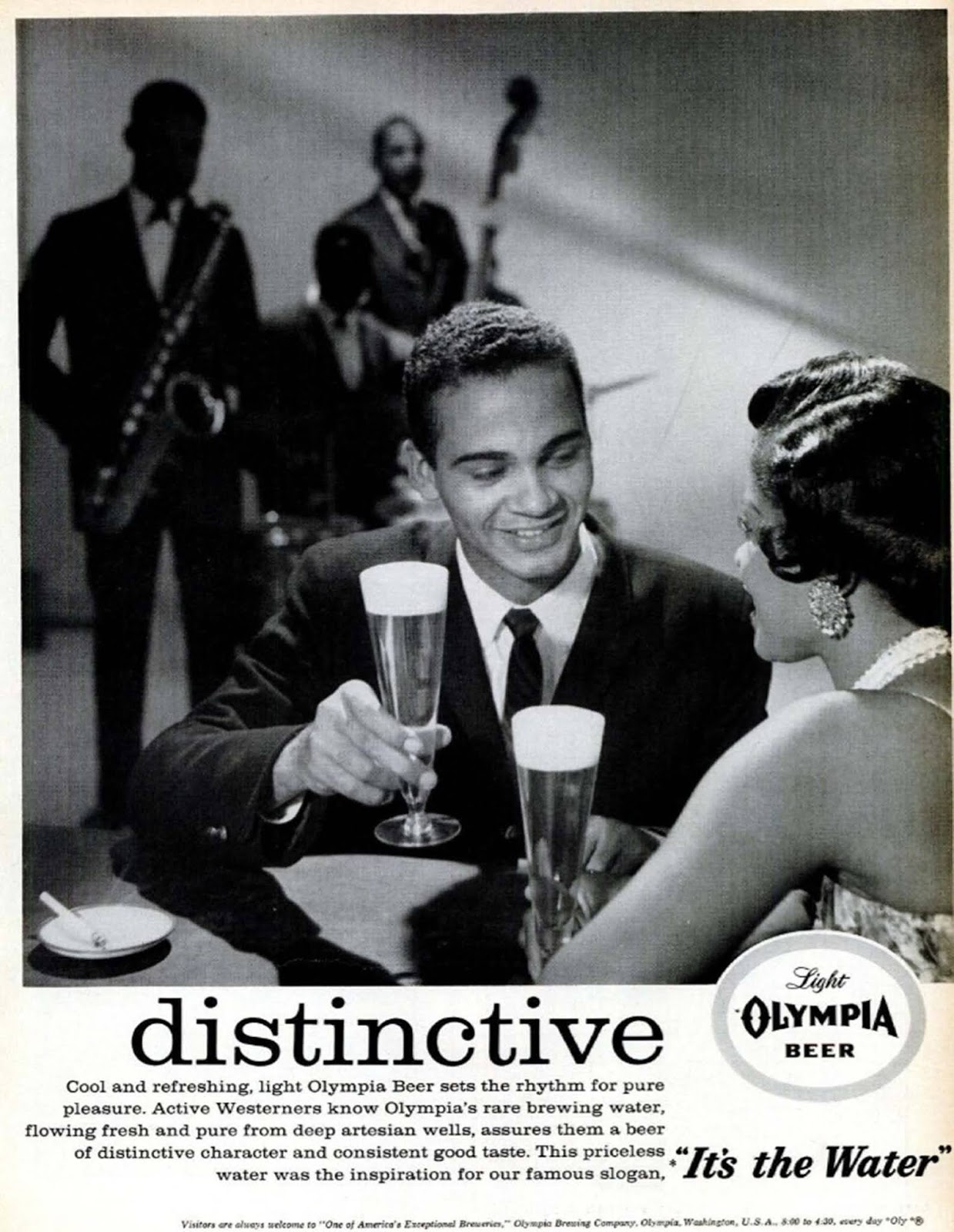

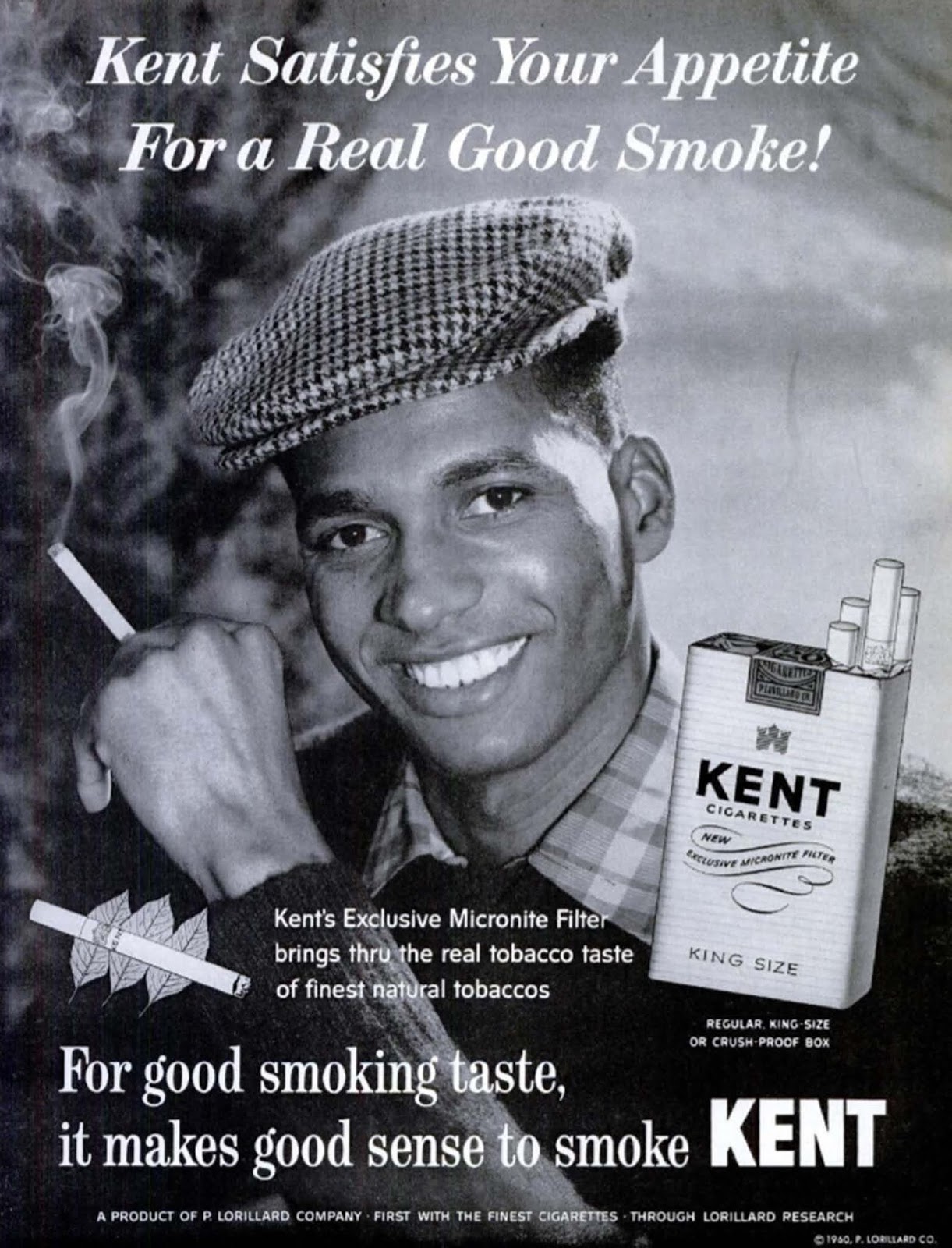

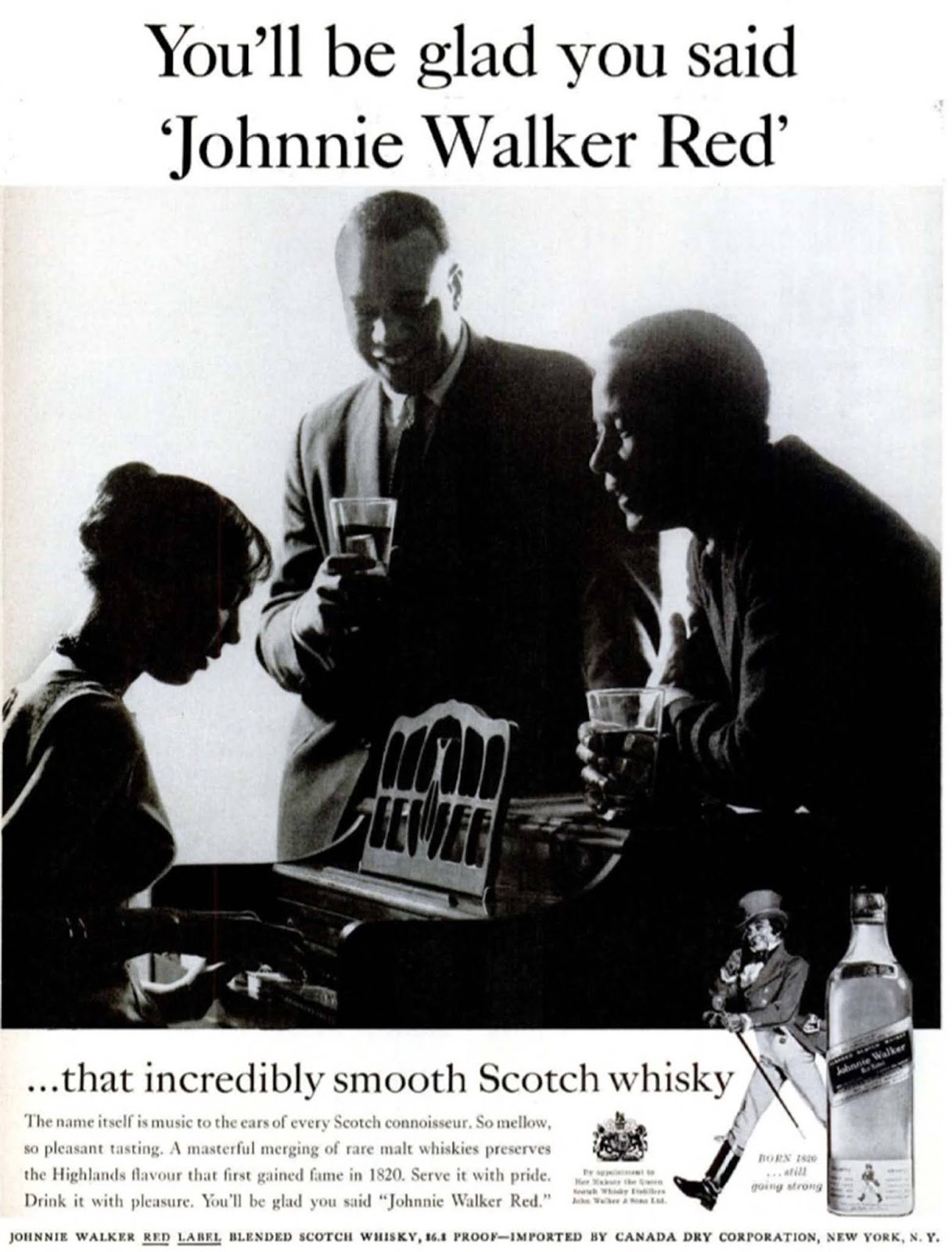

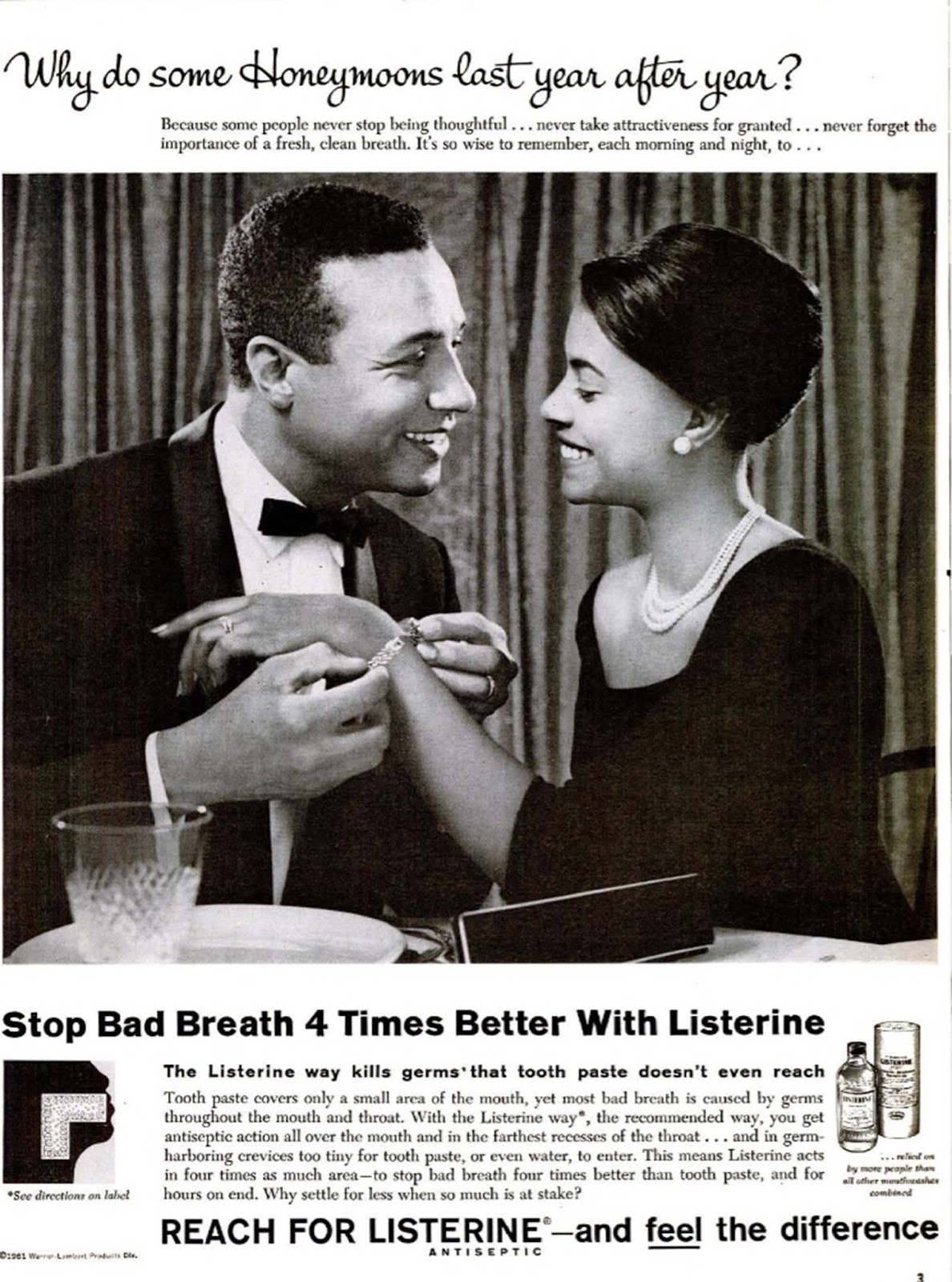

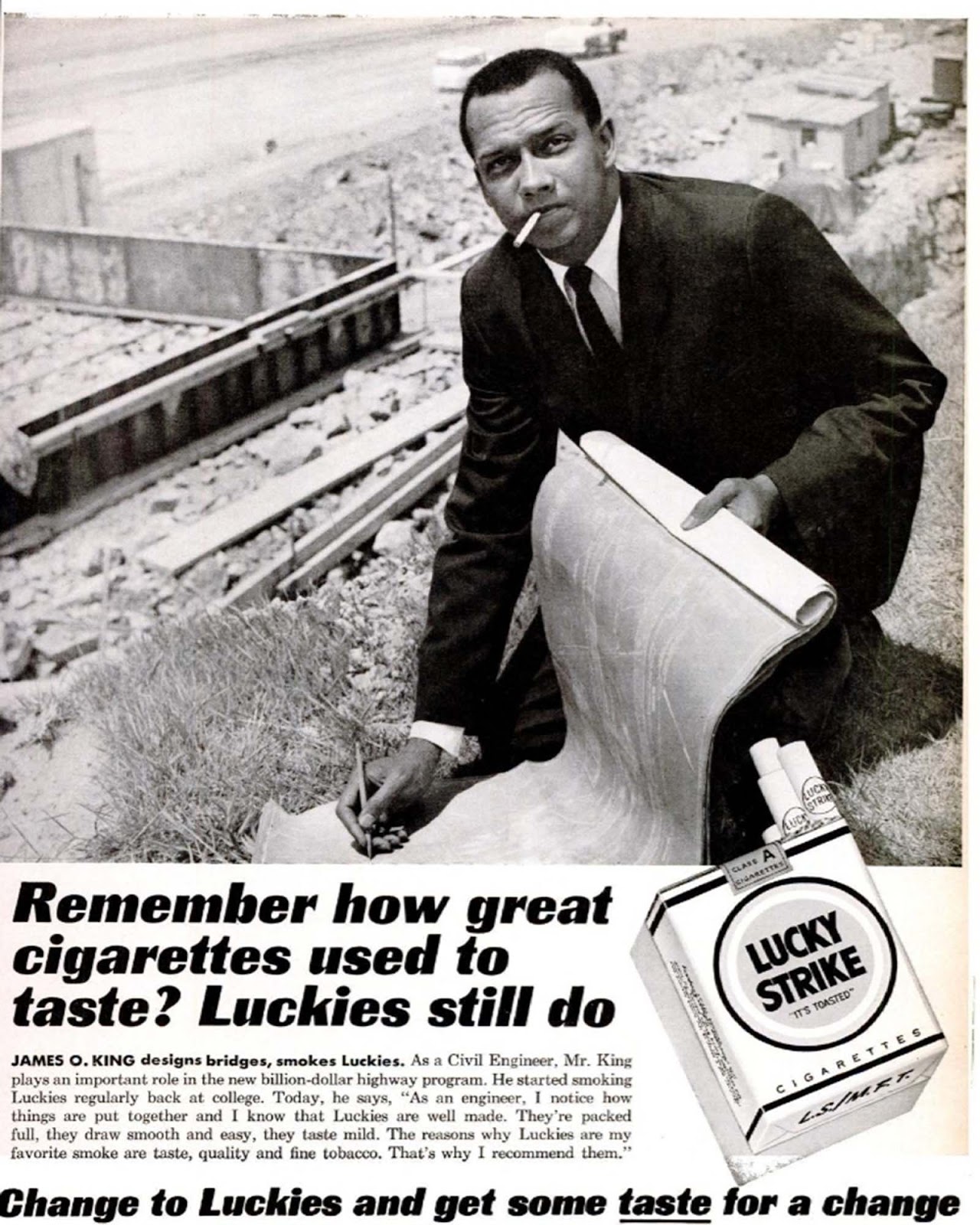

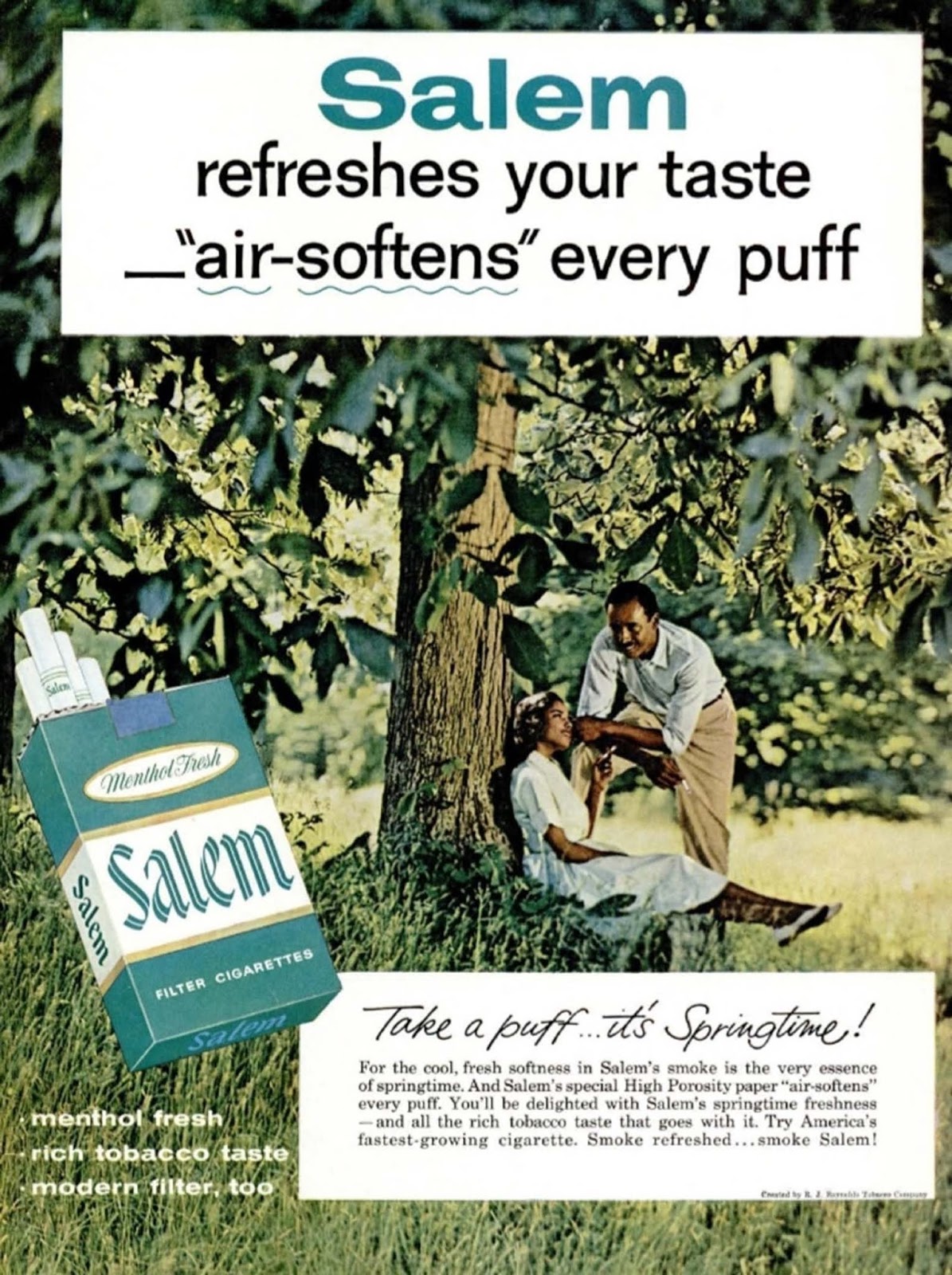

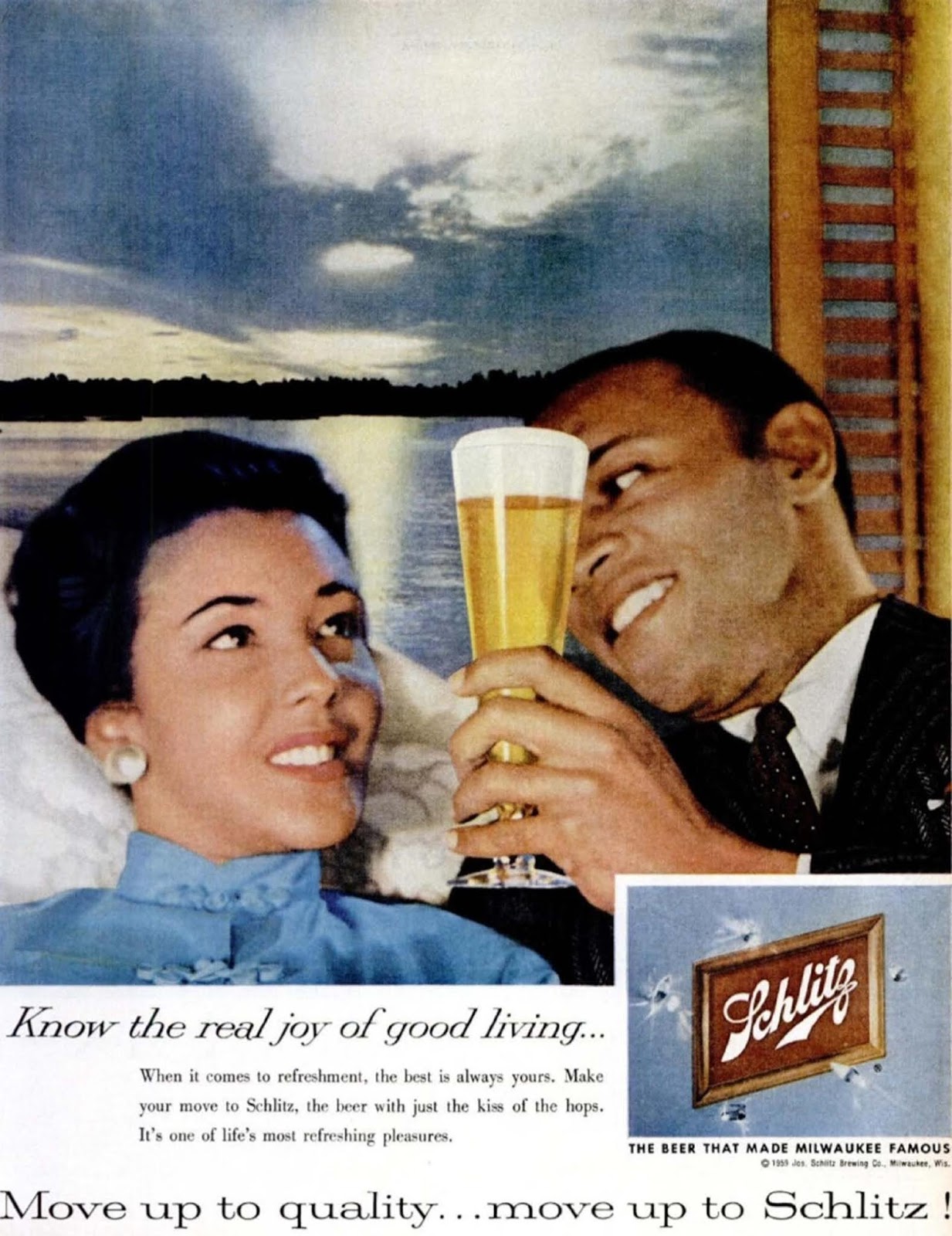

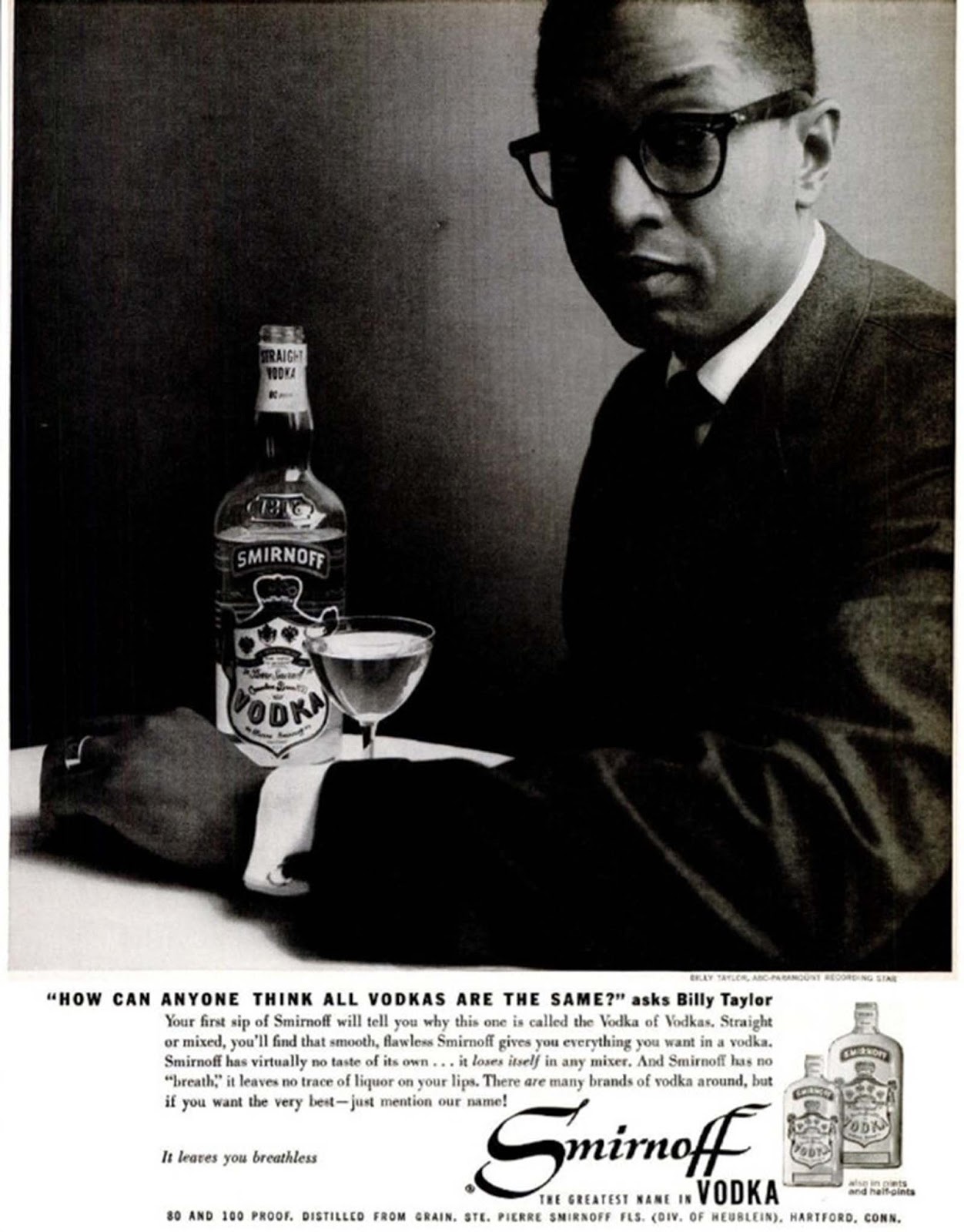

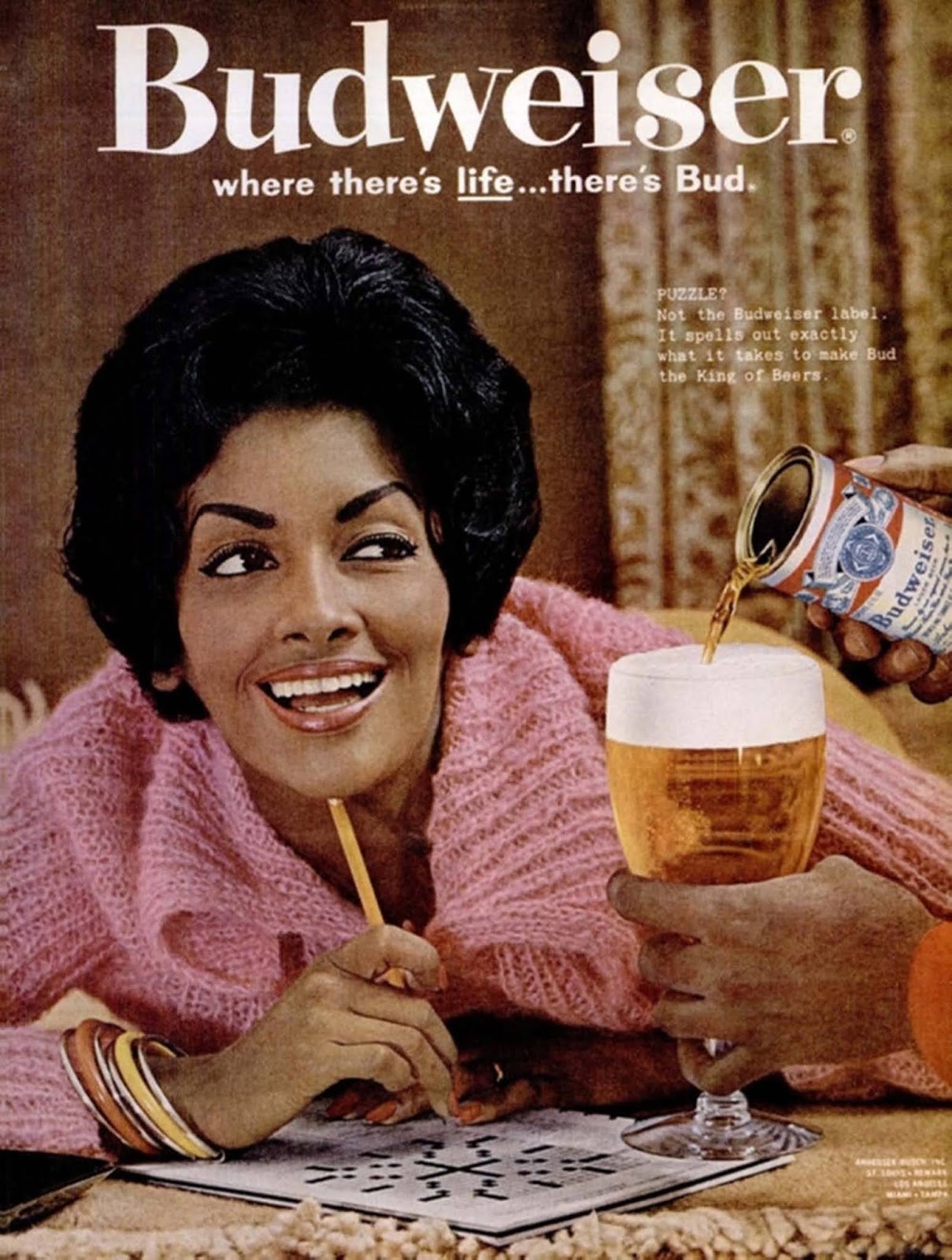

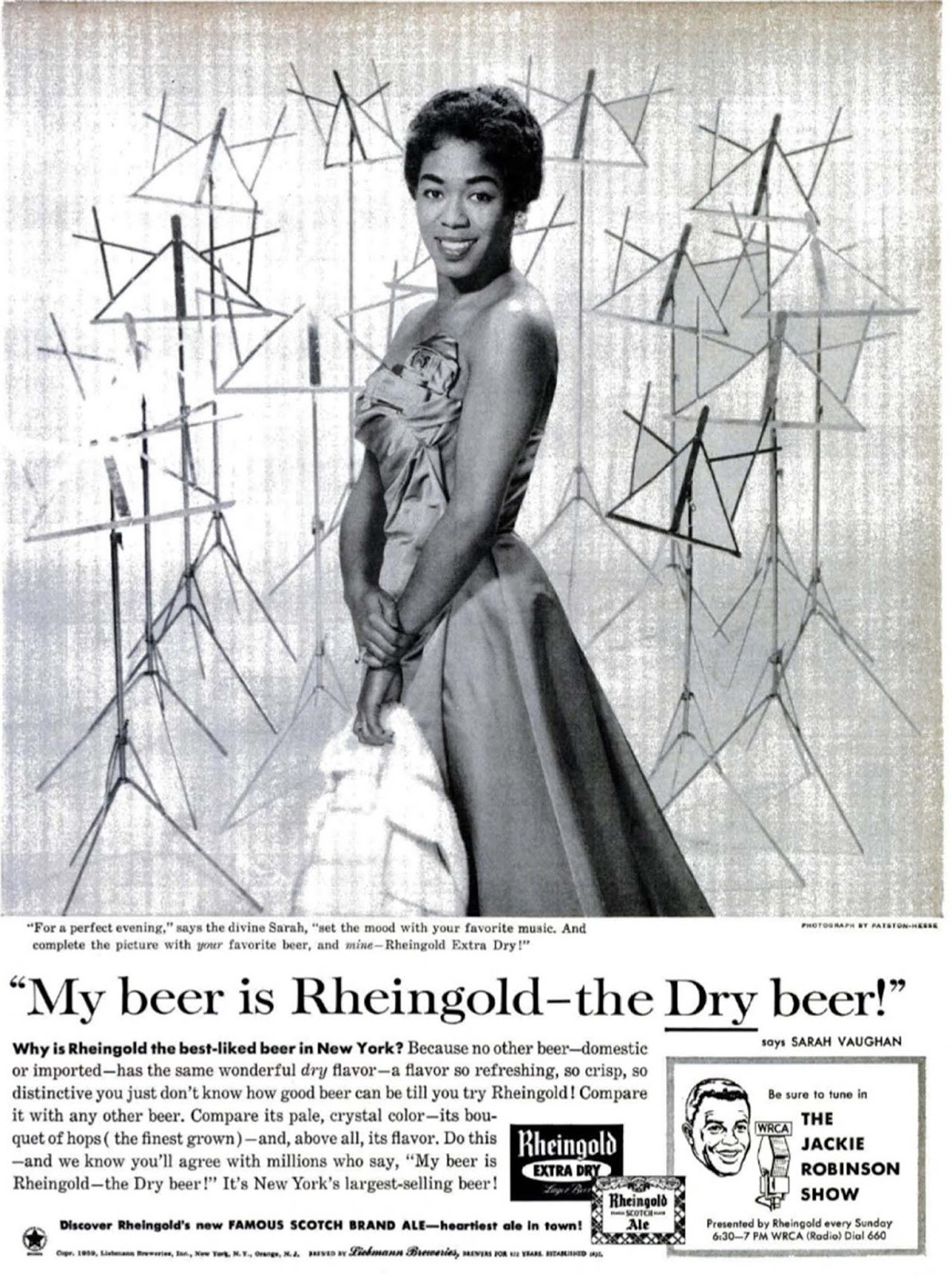

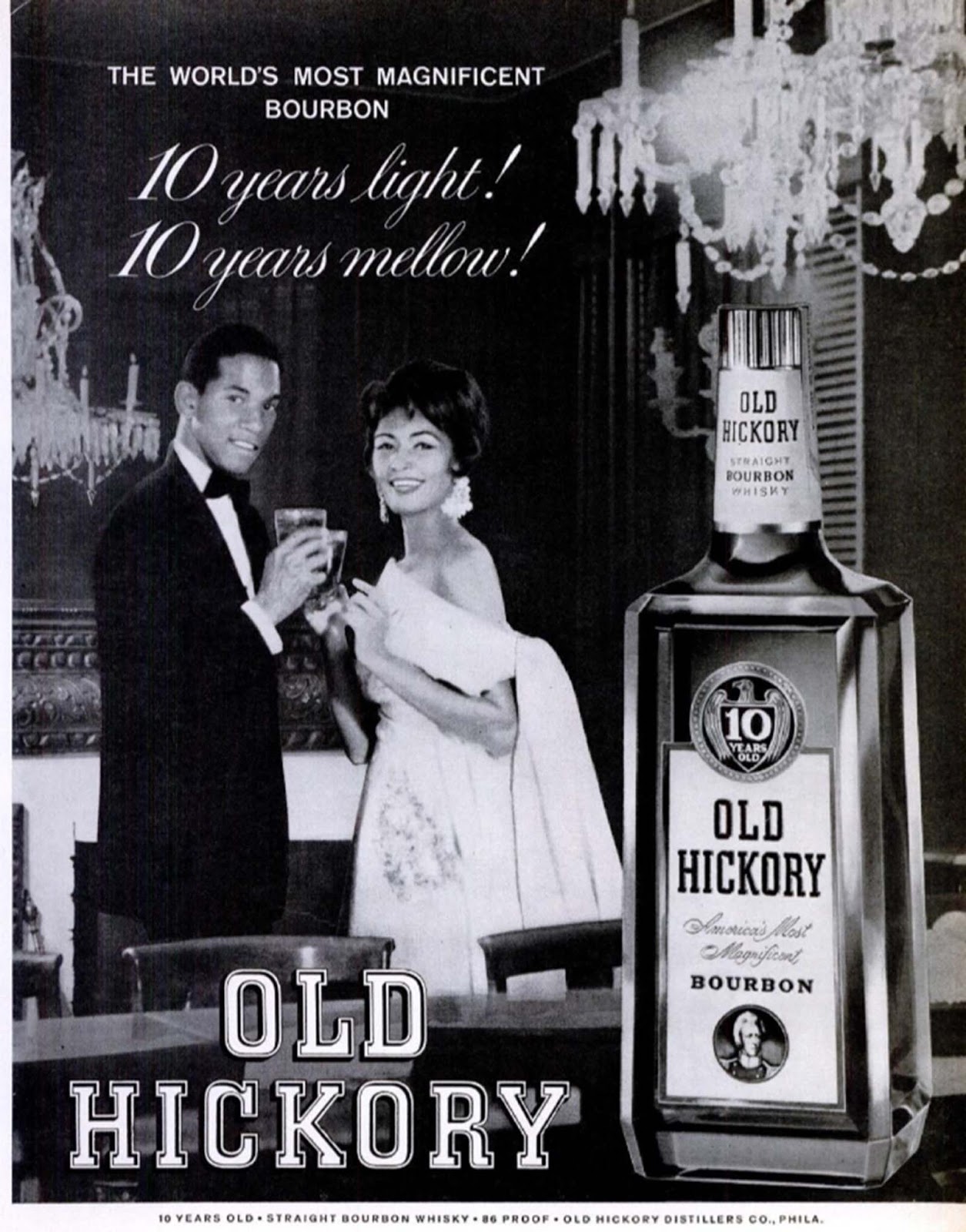

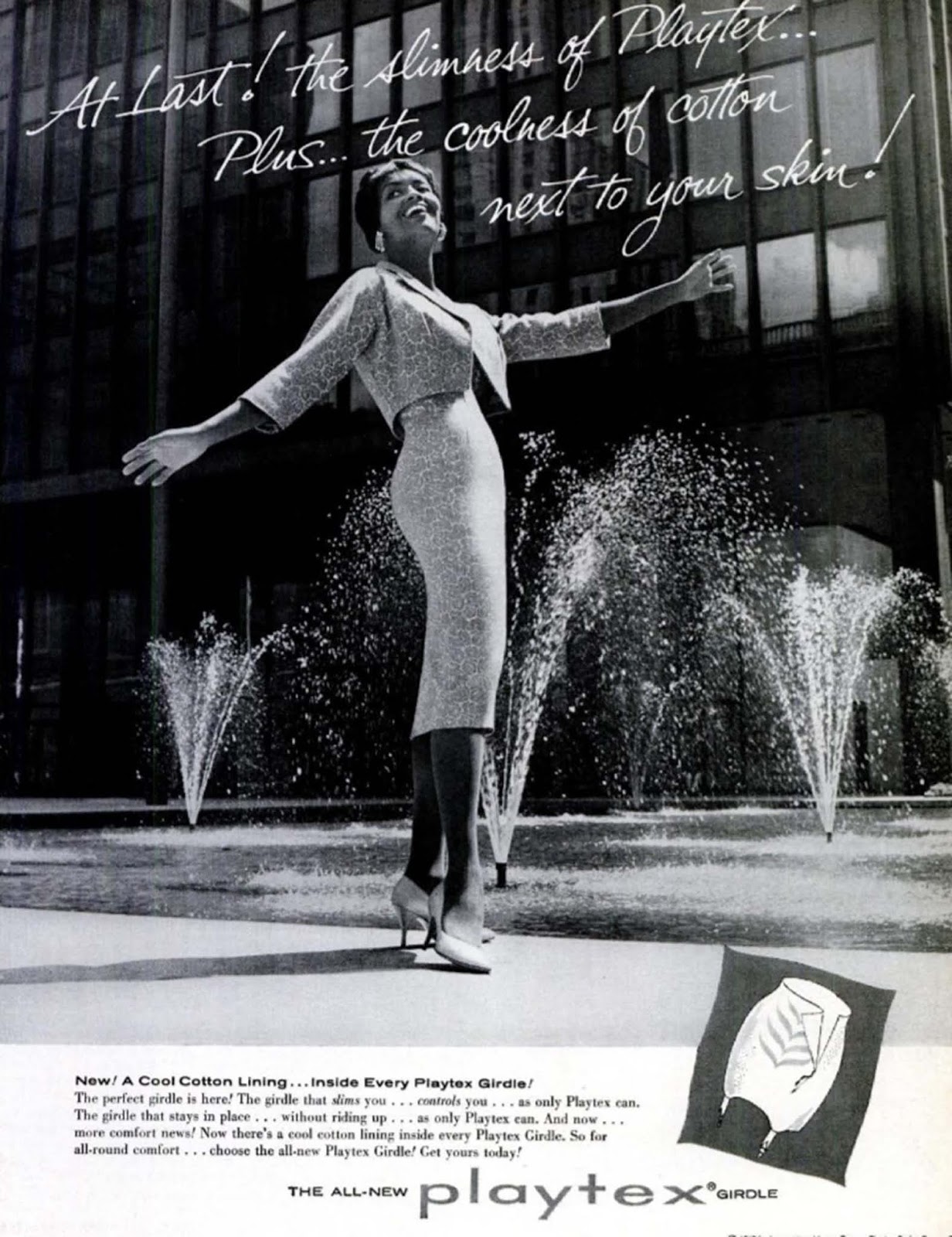

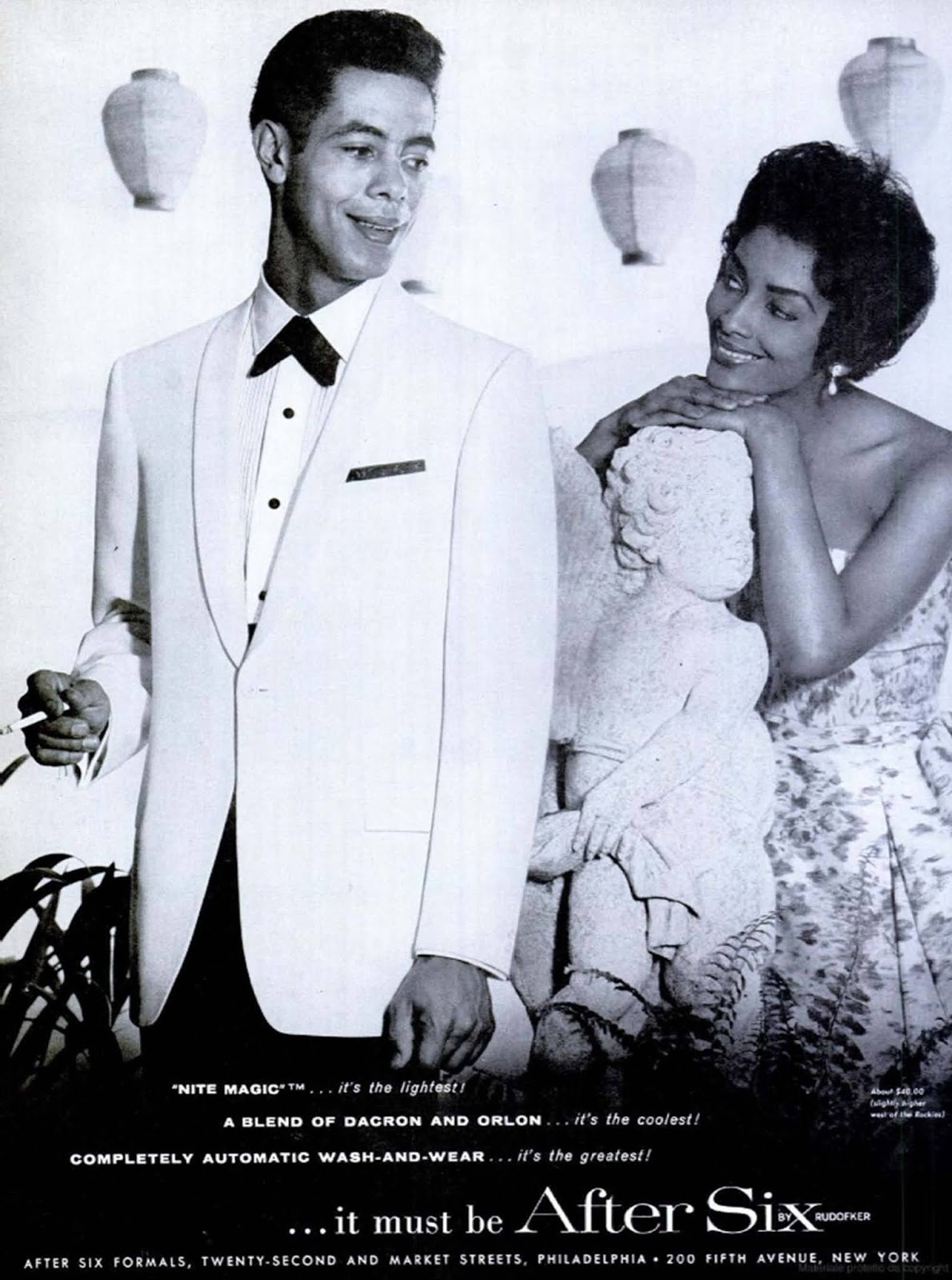

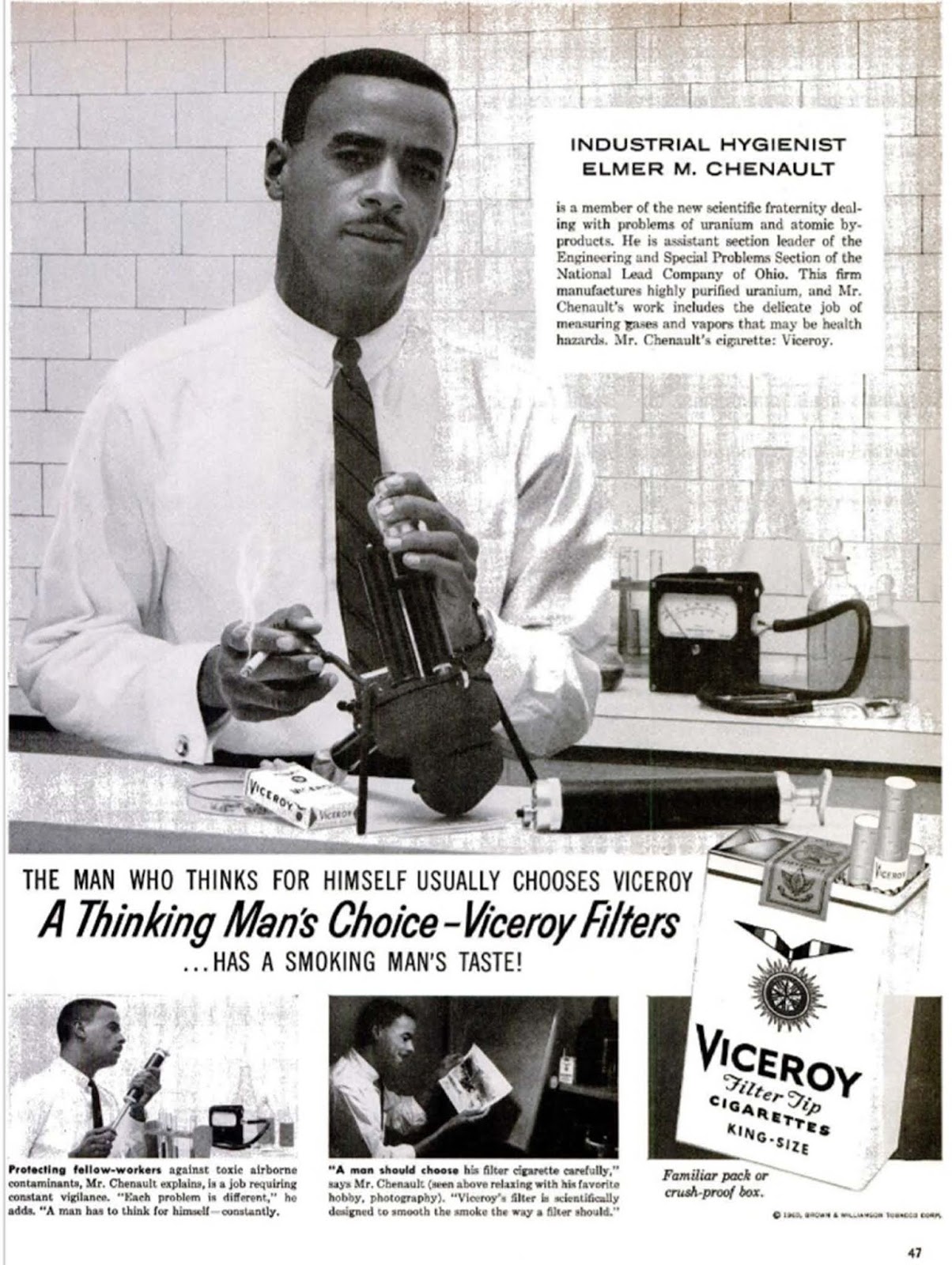

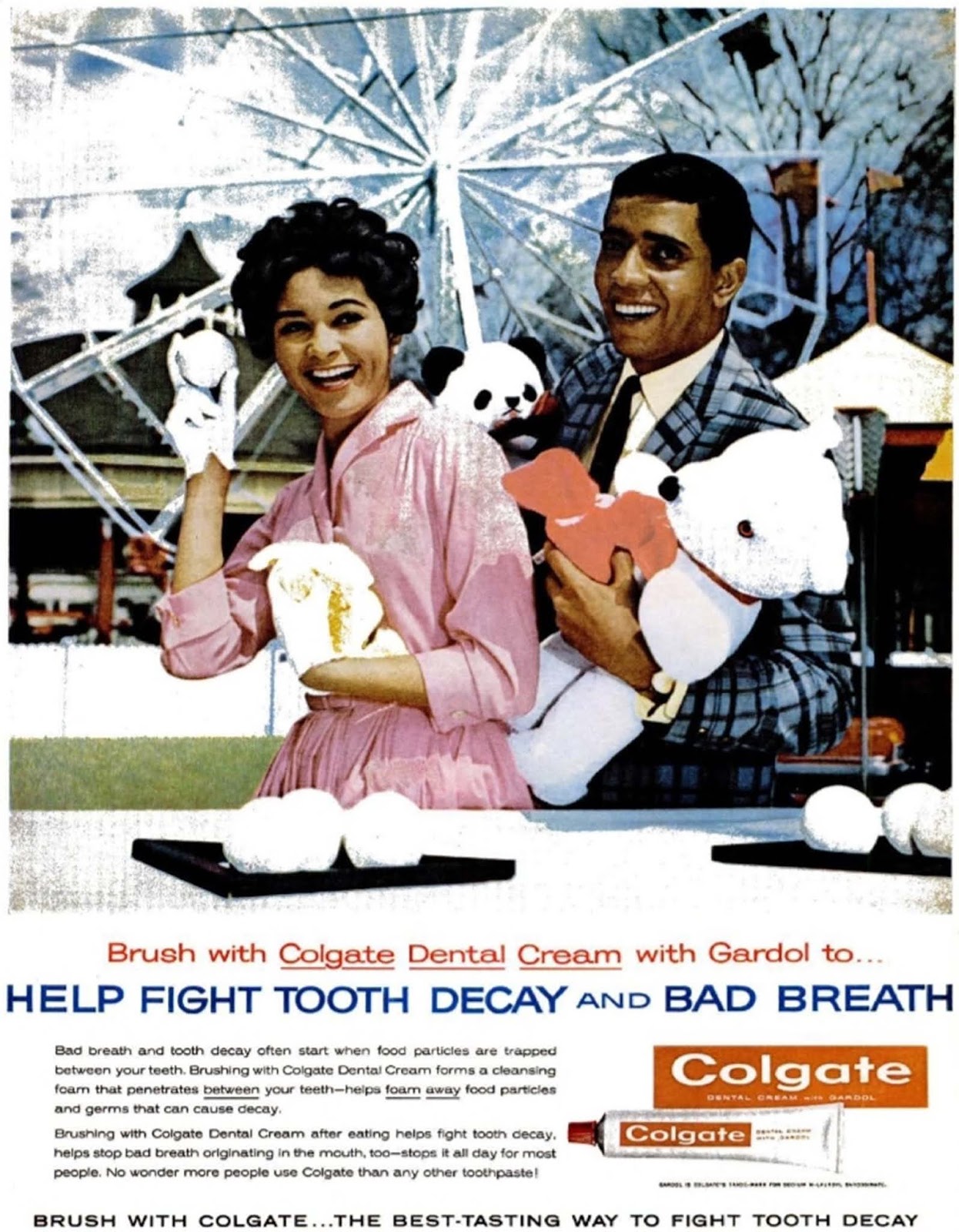

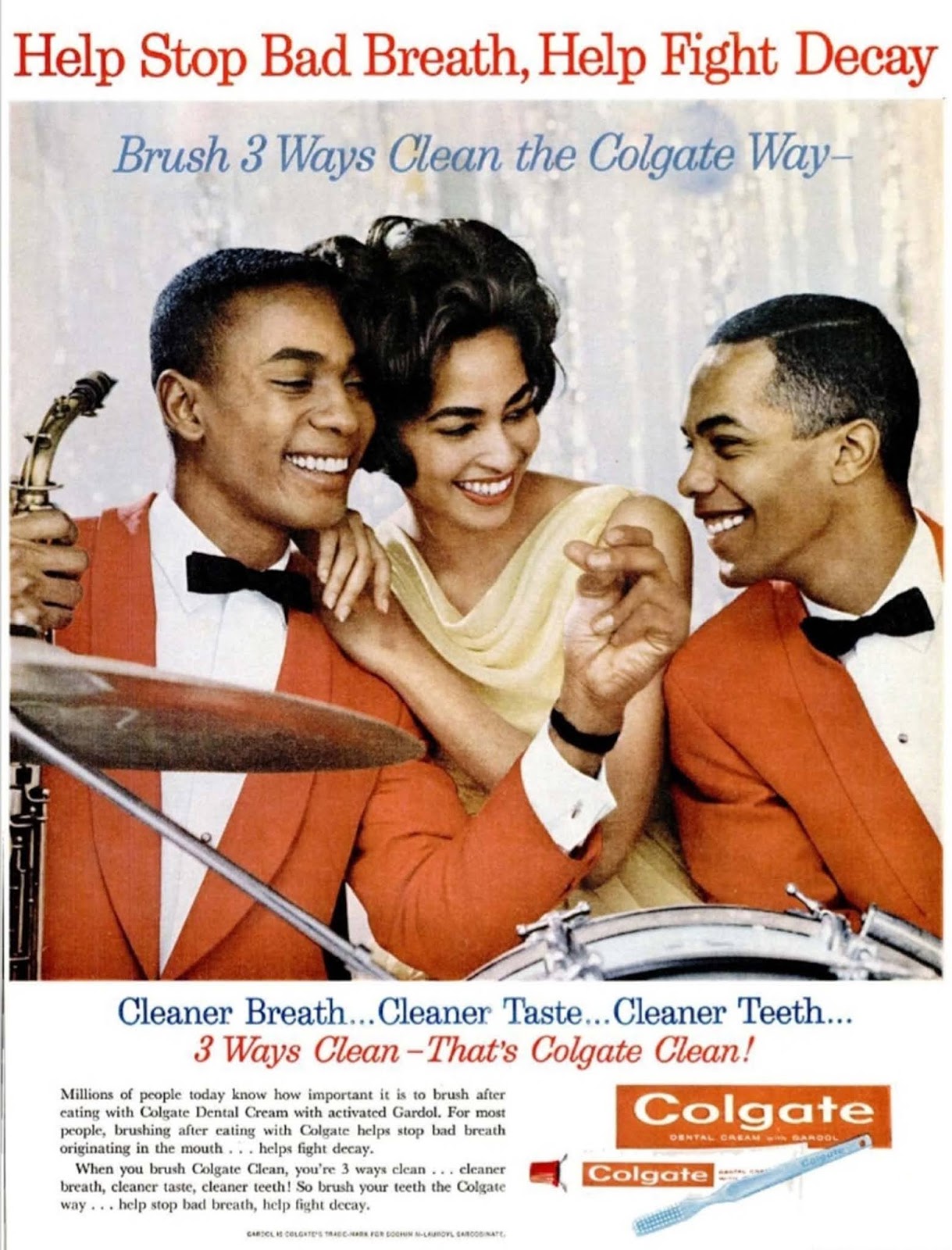

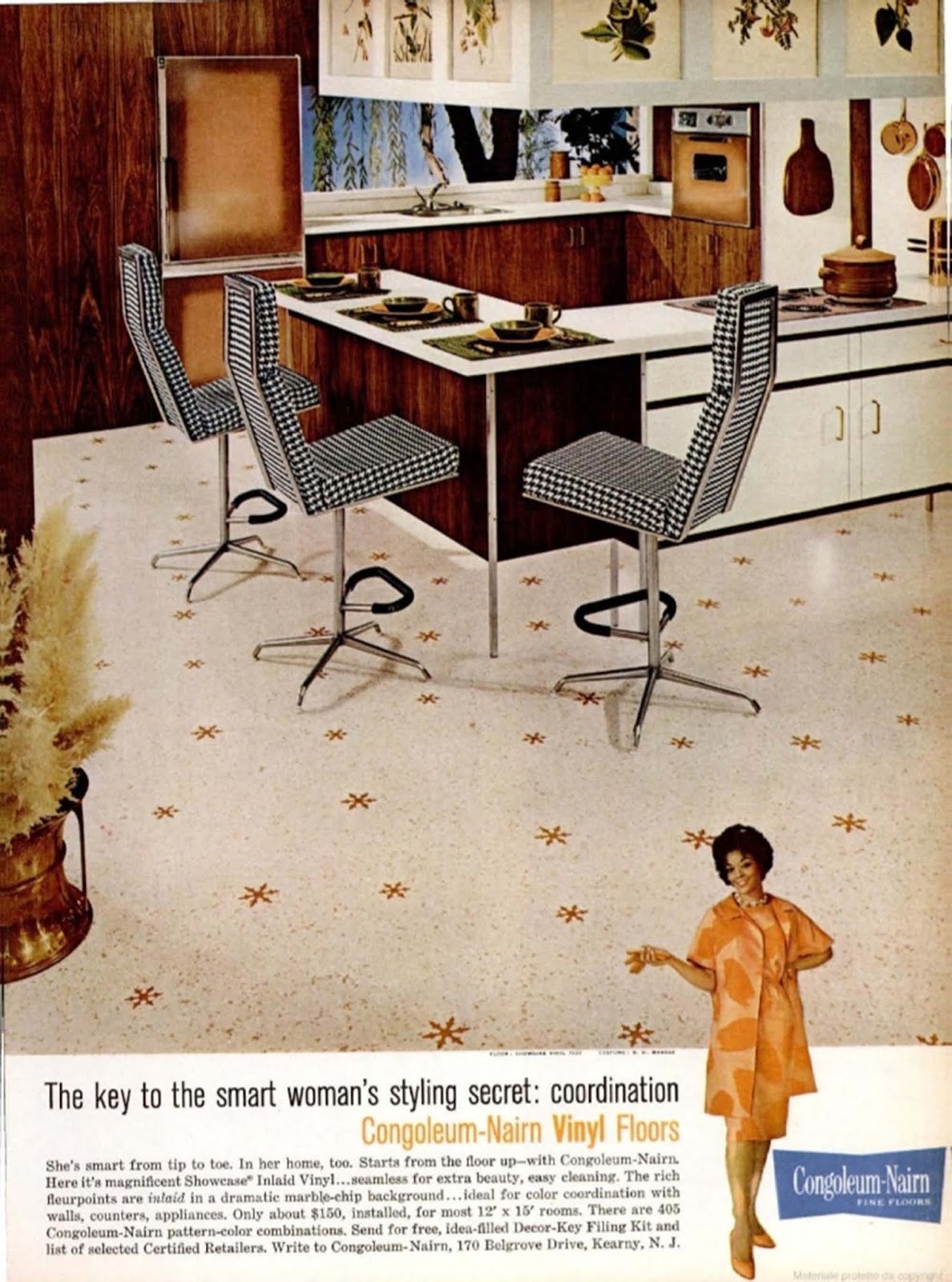

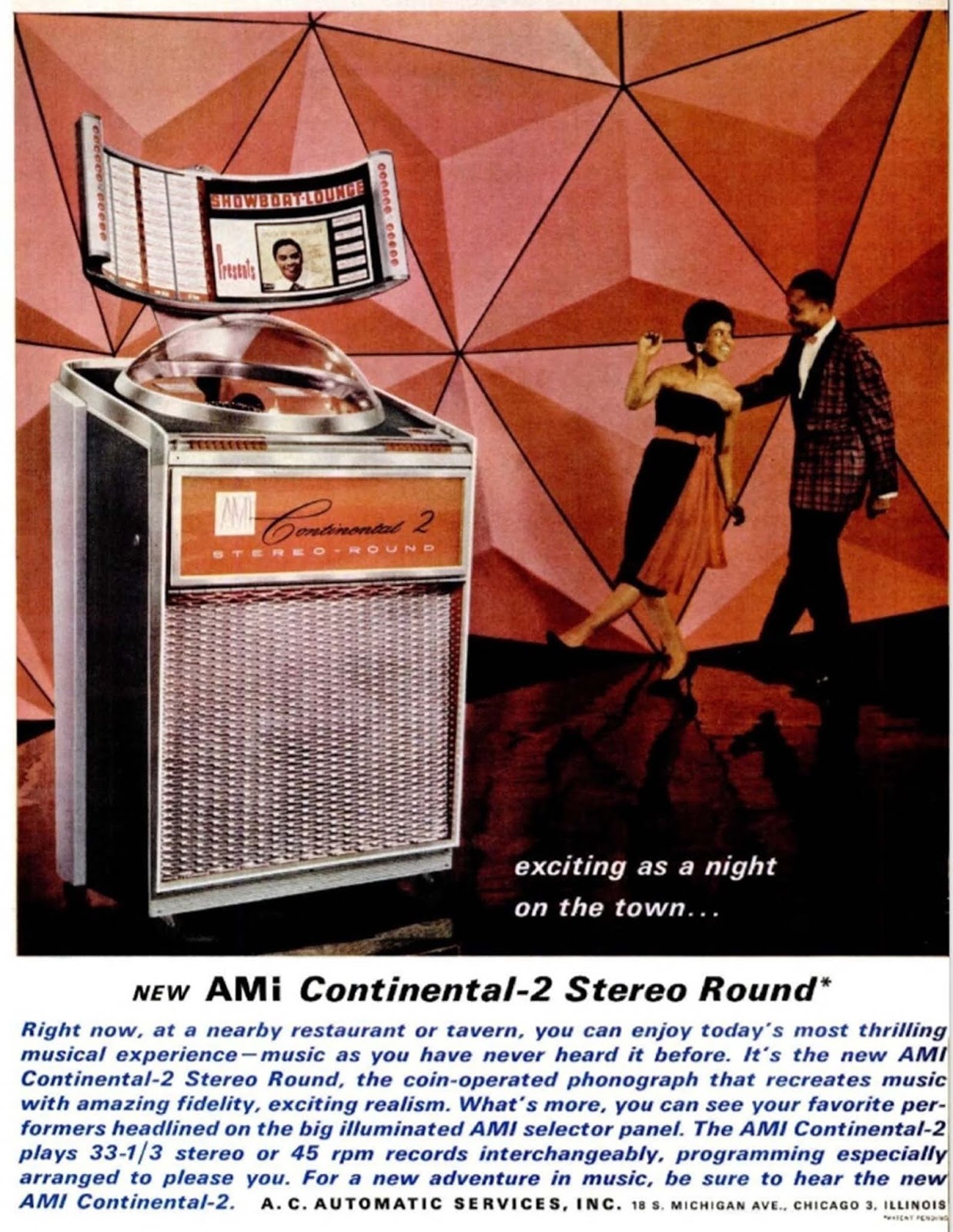

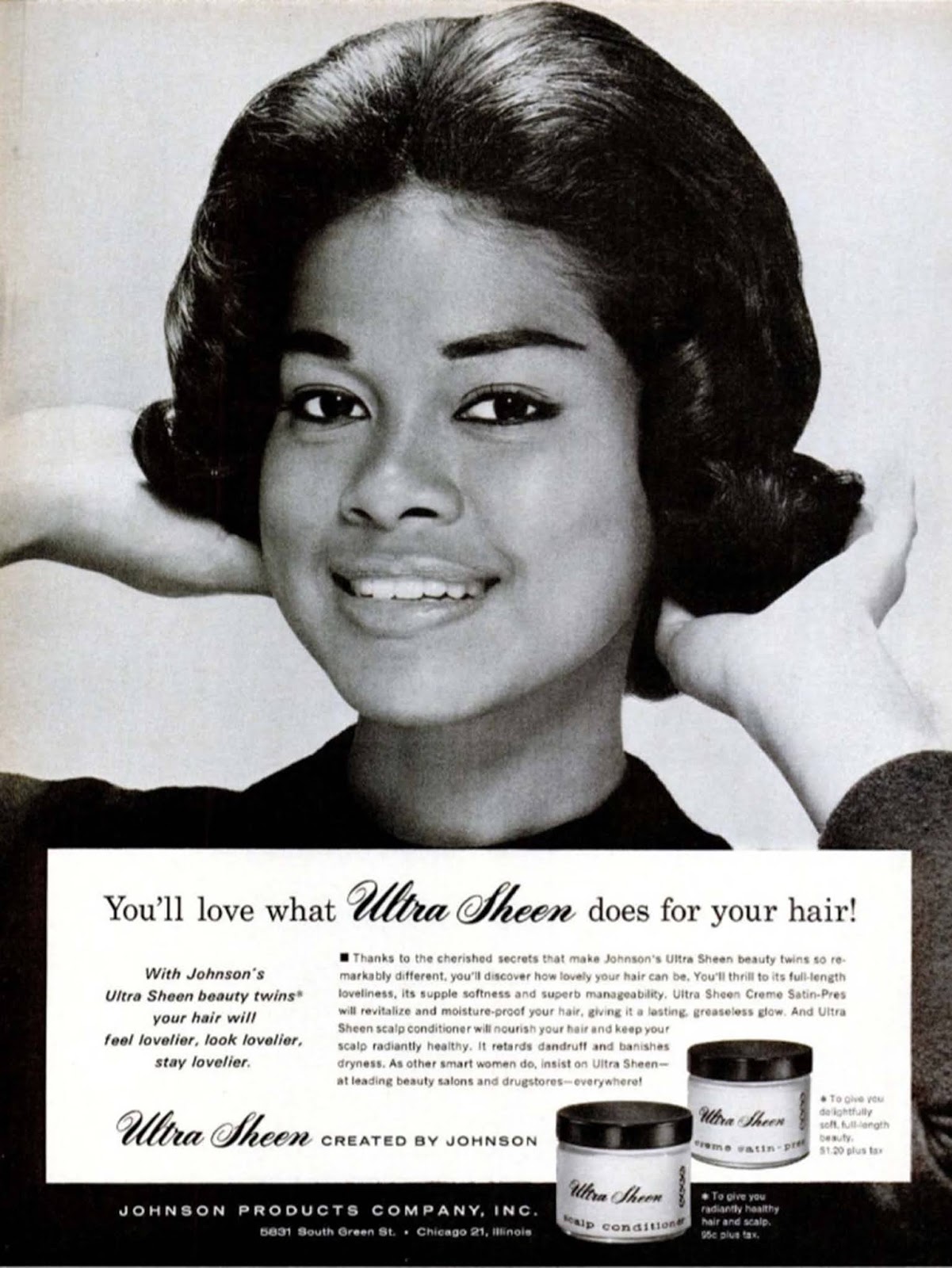

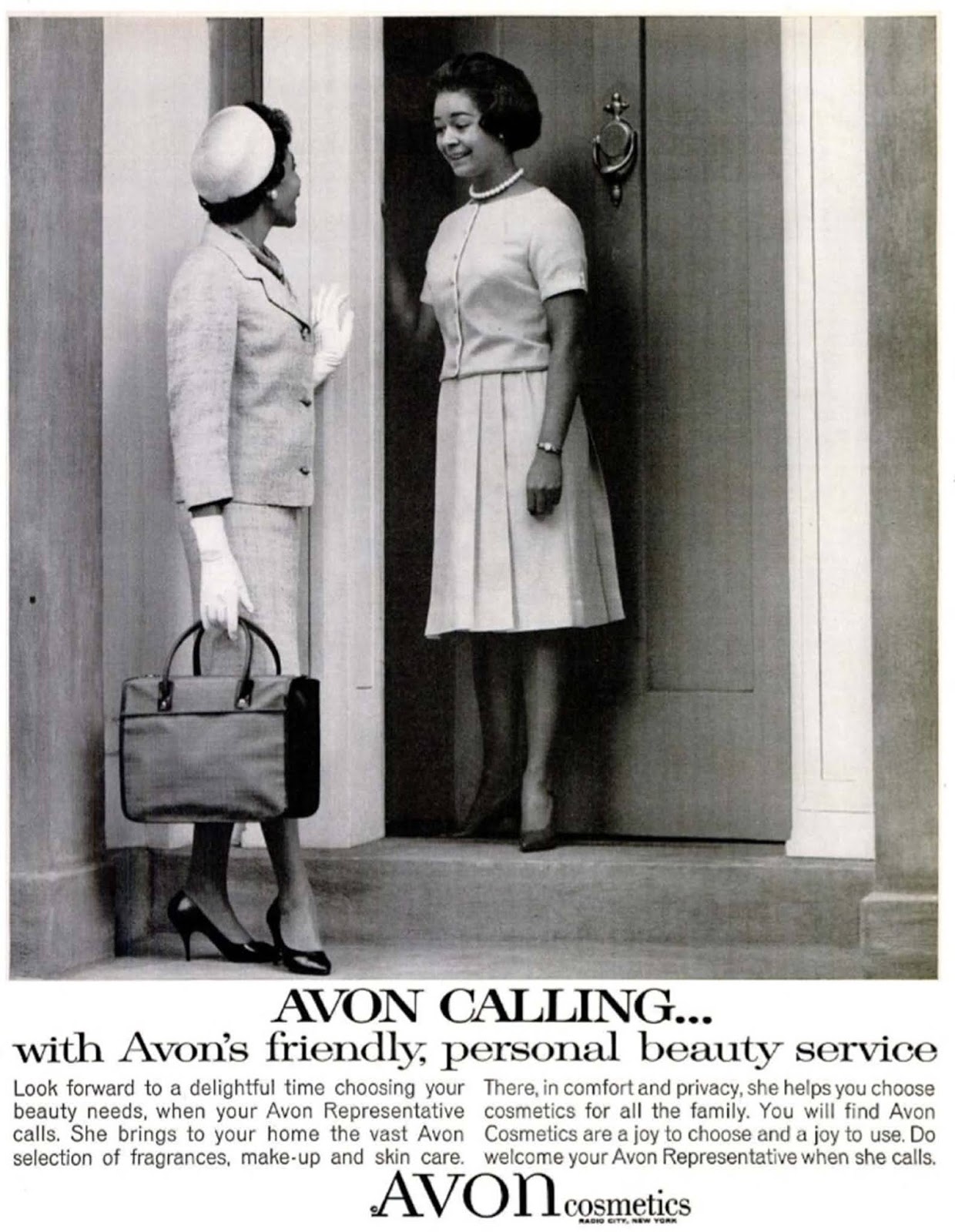

It is said many of these adverts were literally created due to John Harold Johnson, founder of the Johnson Publishing Company dynasty. His hugely successful magazines Ebony and Jet – as well as other titles – catered to the Black middle and upper classes and he felt the readers would be more inclined to buy from mainstream companies that seemed to actually acknowledge them and their spending power. John Harold Johnson personally pitched to brands the idea that they should use Black models to market to his audience if they hoped to see higher sales. When some companies (reluctantly) tried it, they felt the results were so dramatic it ensured they would continue. As a result, Johnson’s publications and, subsequently, others like them saw an explosion of targeted advertising. However, given that Segregation and state-sanctioned discrimination against Black people was still law-enforced at this time – only in these magazines was Black wealth acknowledged and courted. Outside of their own businesses and networks in America, Black people were still banned from entering many shops and actively forbidden from trying on items if entry was permitted. It’s so fascinating that there existed parallel media worlds in one nation, the Black one – where mainstream companies showed Black people as many knew each other to be…and the ‘White’, where Black people were totally ignored.

African-Americans in the advertising industry

(From AdAge Encyclopedia) In the U.S., African-Americans first appeared in ads during the 1870s when color lithography was first used to print trade cards. The cards varied greatly in subject matter, although sports figures and ethnic humor were the two most popular motifs. Some of the images were blatantly racist. One of the most defamatory showed abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass with his second wife, a white woman, taking a product called Sulpher Bitters to lighten her skin. From the beginning of the 20th century to the mid-1960s, advertising using stereotypical images of African-Americans was pervasive throughout the U.S. Some of the images became American icons and are still used on products today. Blacks were made to appear subservient and ignorant as well as ugly and grotesque. And if domestic work or menial labor was involved, blacks were depicted as being best suited for the job. Aunt Jemima is one of the best known of the stereotypical African-American ad characters. The Aunt Jemima trademark, which first appeared in 1889, was a historical development: Aunt Jemima, the first ready-made pancake mix, foreshadowed the era of convenience products; it was the first product to use a black person as a trademark; and the product’s marketer was the first to promote the idea of giving a product away to attract new customers. From the end of slavery to the period of the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s, ads in the U.S. continued to show blacks as Aunt Jemimas, Uncle Bens and Rastuses individuals subservient to whites. Trade cards, ad stamps, blotters, tins and bottles commonly portrayed blacks with thick lips, bulging eyes and distorted grimaces. Many saw these images of servility as promoting a type of psychological bondage equally as detrimental as physical enslavement. African-American consumers were targeted as a specific market segment as early as 1916, when a gas company in Rock Hill, S.C., worked with a church group and the local government to conduct a cooking school for Black servants. Advertisements for their efforts led to the sale of 12 kitchen ranges by the gas company. The early recording industry discovered an important market among blacks in 1920 when Columbia Records issued “Crazy Blues” by Mamie Smith. And in 1922, Fuller Brush Co. hired four teachers as salespersons for the black consumer market in Tulsa.

(Photo and article credit: TheAfternoonStandard / Ebony / Jet / AdAge Encyclopedia). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe