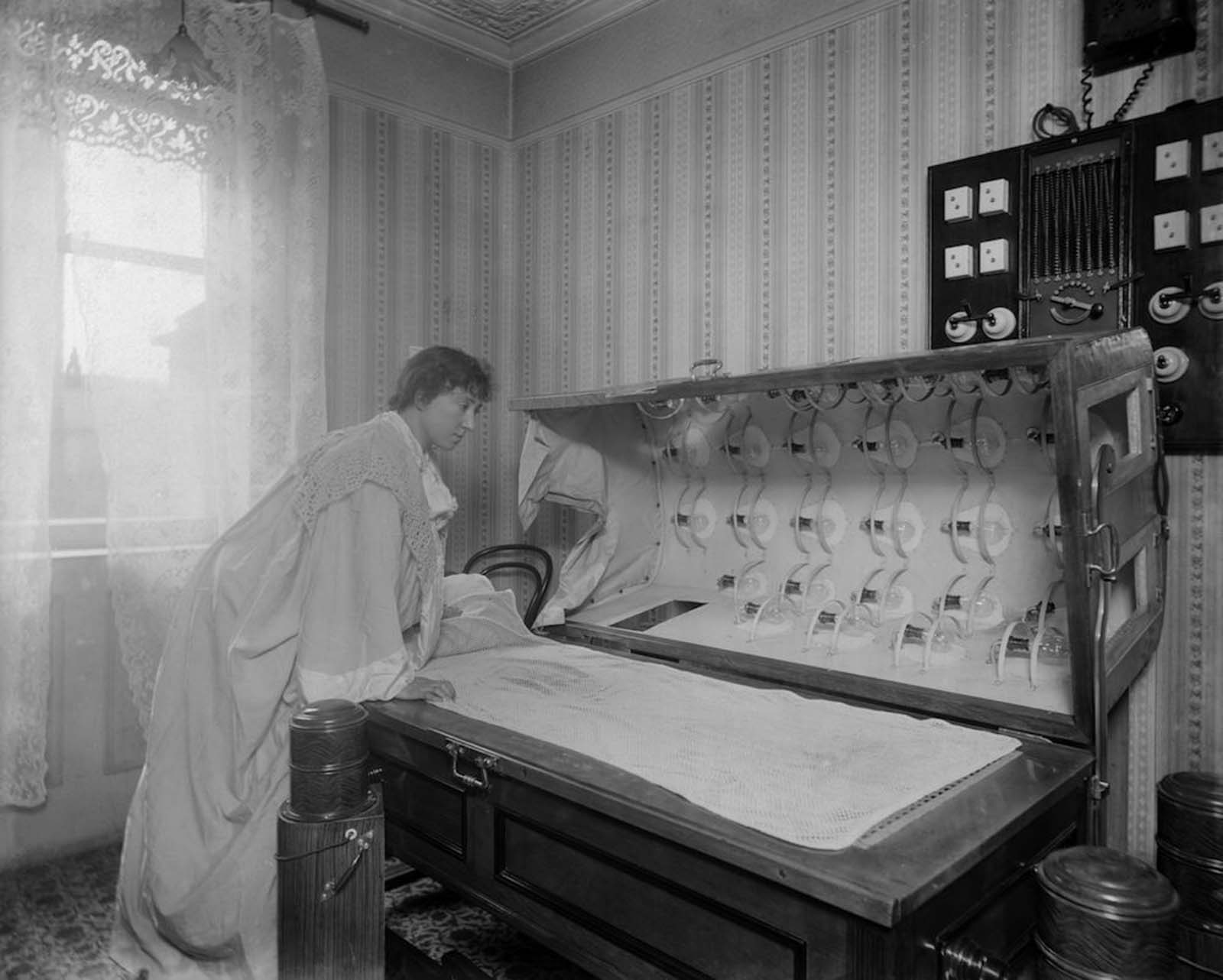

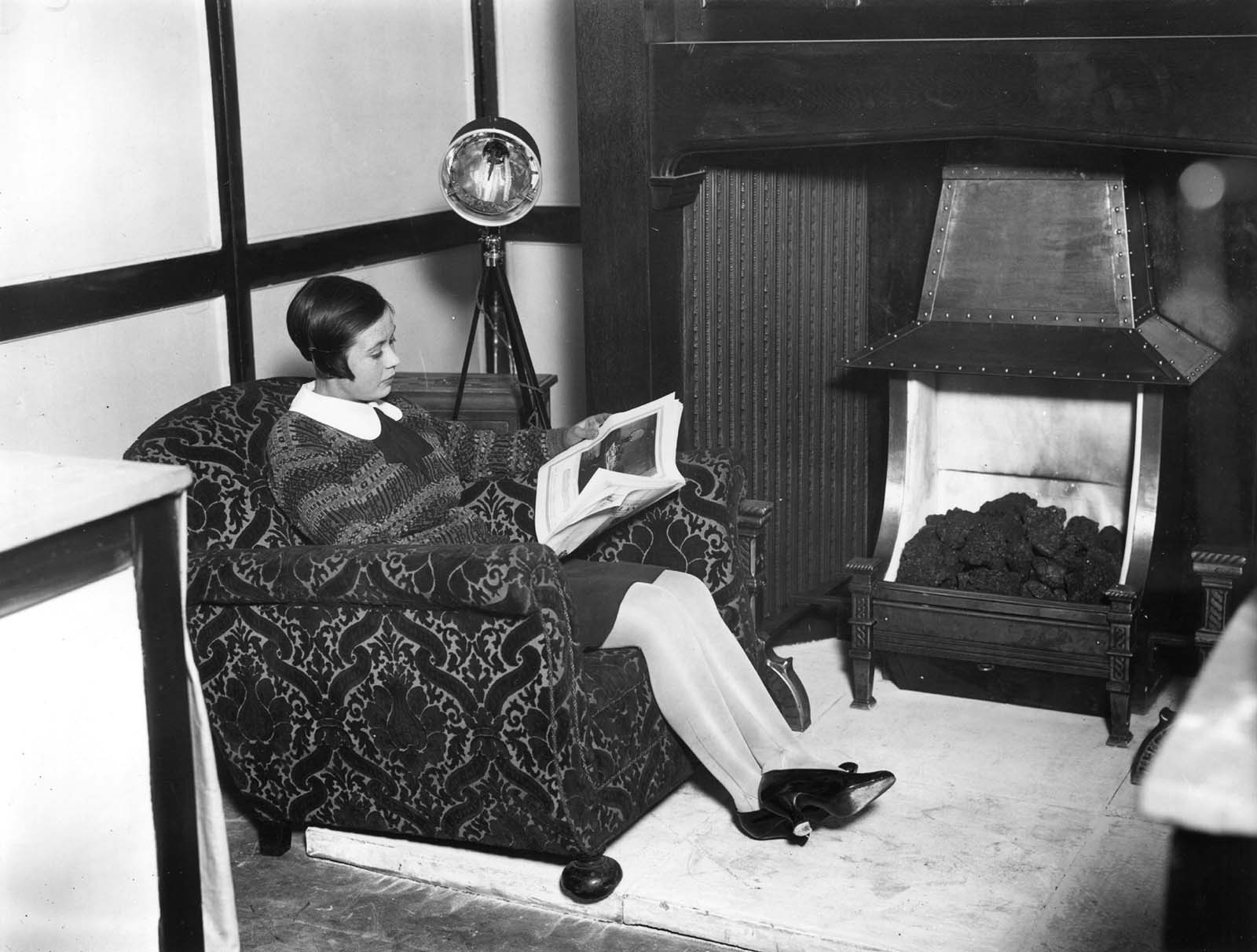

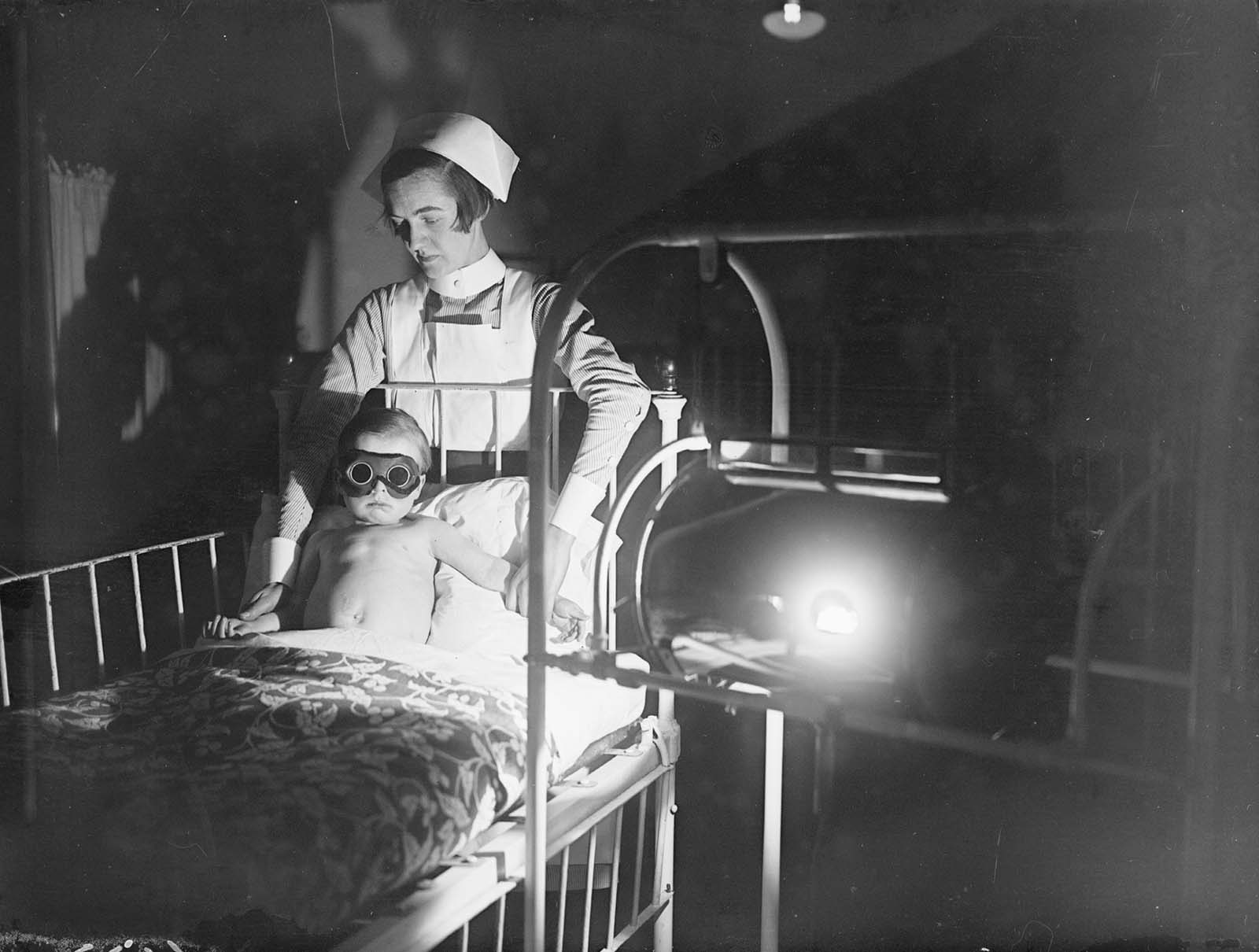

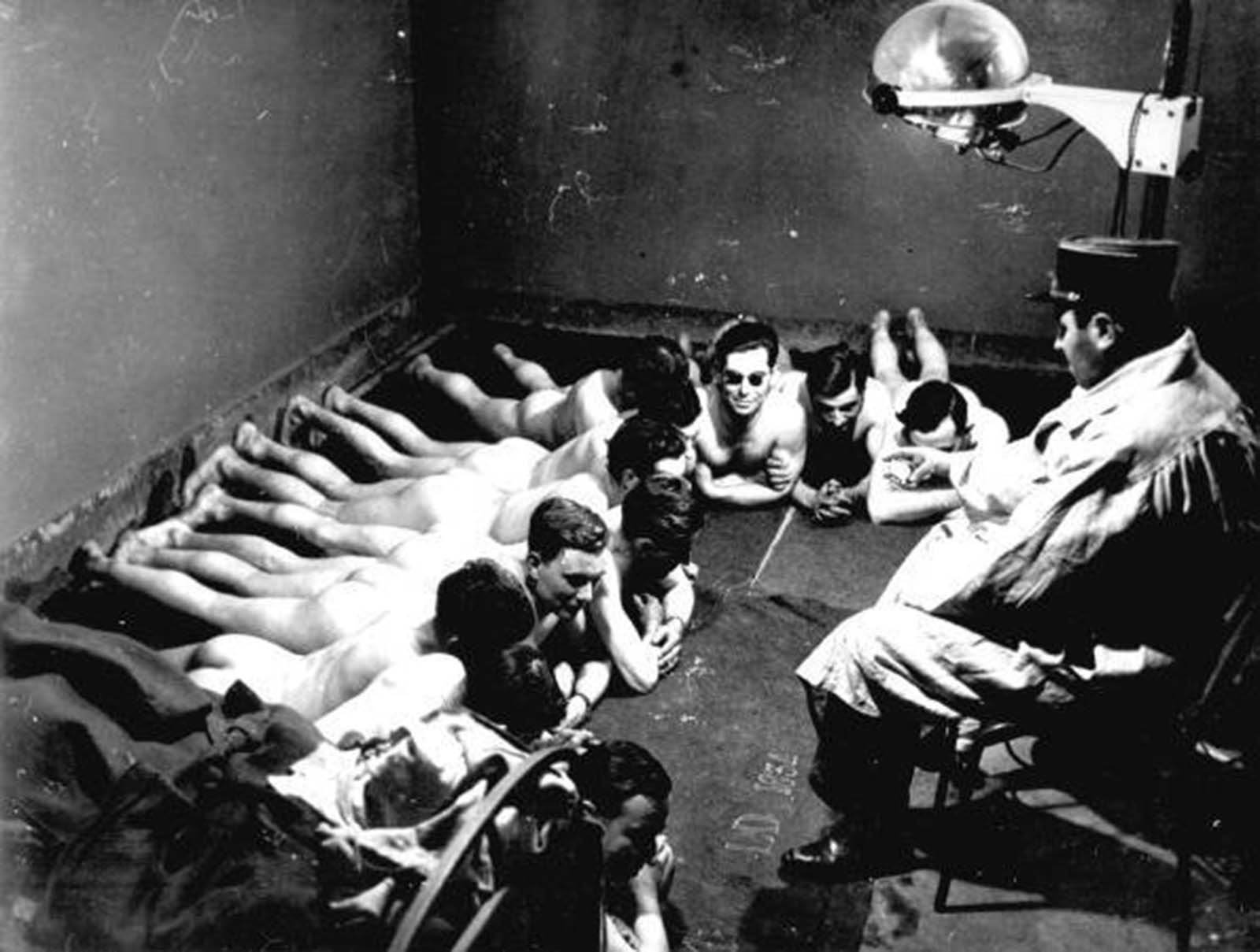

The treatment had two branches: heliotherapy (natural sun therapy) and phototherapy (artificial light therapy). These progressive therapies presented and sold light as curative and transformative. From the late 1800s, light therapy – sometimes called phototherapy – became a key part of certain treatment regimes for tuberculosis, notably tuberculosis of the bones, joints and skin, as prolonged exposure to sunlight can kill the bacteria which cause the disease. Infected children who were sent out to special homes and hospital retreats were encouraged to spend as much time outdoors as possible. These children had often come from dark and dingy city slums and exposing their skin to sunshine raised their levels of vitamin D, which also helped them fight the bacteria. As sunlight is not available at all times, artificial alternatives were developed that could mimic the Sun’s beneficial effects. The Finsen lamp, invented by Danish Faroese physician Niels Ryberg Finsen, is perhaps the best-known example. An ultraviolet lamp, it allowed flexible treatment in all seasons and its rays could be concentrated onto the most affected parts of a patient’s body. Its greatest success was in the treatment of lupus – tuberculosis of the skin – for which Finsen was awarded a Nobel Prize in 1903. Sun therapy (heliotherapy) was very popular in Europe from around the turn of the century until the late 1930s. One of its foremost practitioners was Dr Auguste Rollier who established a sun-therapy clinic in Leysin in the Swiss Alps. He treated all sorts of patients, very effectively, particularly those with TB – his patients would be wheeled out onto a large sundeck for specific periods each day. In the 1930s, Charing Cross Hospital in London used ‘sun-lamps’ to treat circulatory diseases, anaemia, varicose veins, heart disease and degenerative disorders. Then in the early 1940s in the United States, Emmitt Knott developed a very interesting device – a haemoirradiation machine. Knott found that irradiation of just 50±100cc of blood with ultra-violet light and retransfusion back into the patient had a dramatic impact in the treatment of puerperal sepsis, peritonitis, encephalitis, polio, and herpes simplex. By 1947, somewhere in the region of 80 000 patients had been treated with reported success rates of 50-80%. The light therapy practice is now treated with much greater caution (as it should be): overexposure to ultraviolet light over a long period of time can lead to melanoma and other skin cancers. (Photo credit: Fox Photos / Hulton Archive / Library of Congress). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe