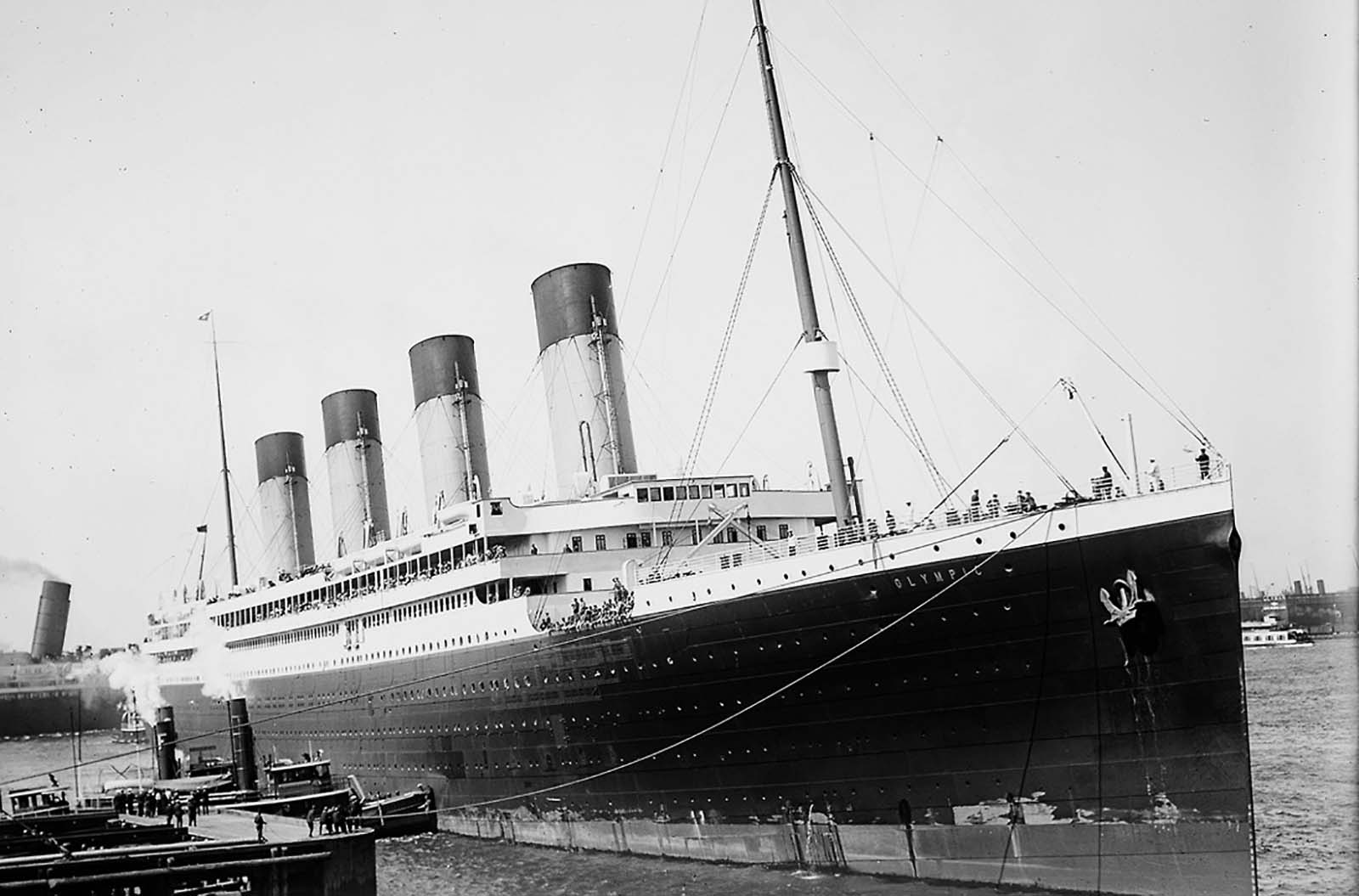

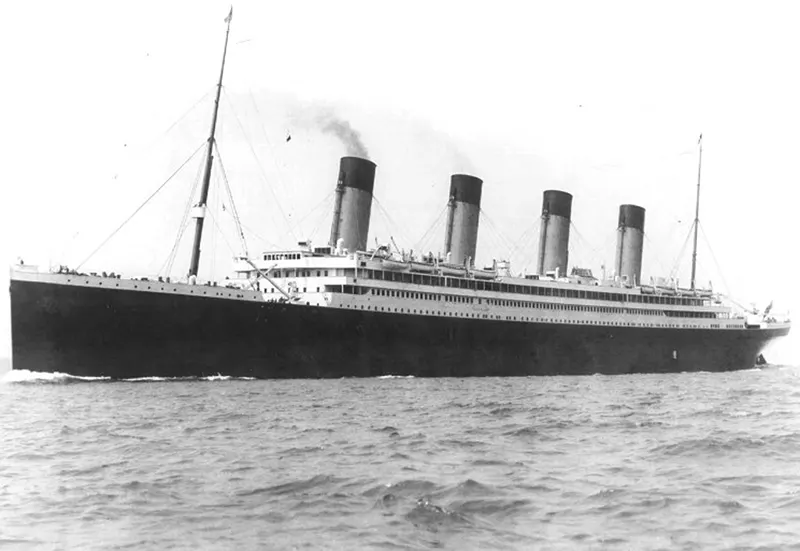

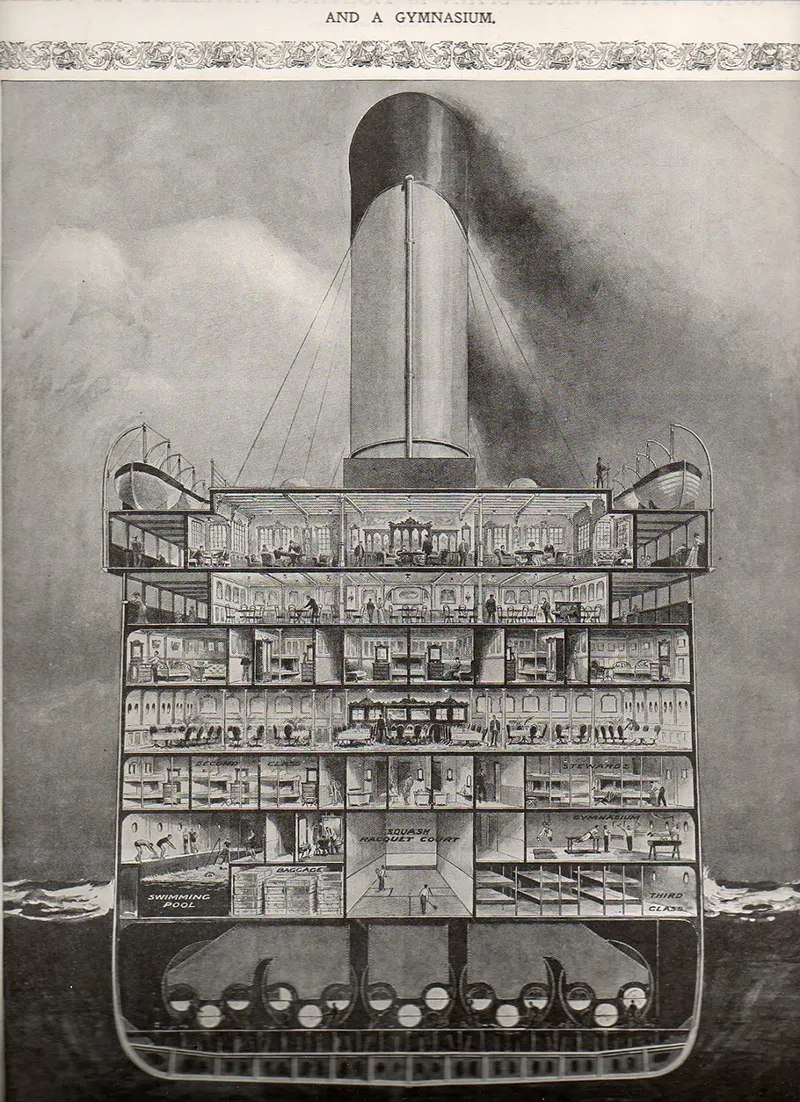

Olympic also held the title of the largest British-built liner until RMS Queen Mary was launched in 1934, interrupted only by the short careers of Titanic and Britannic. The keel for the Olympic, Harland & Wolff Yard No. 400, was laid on December 16, 1908 under the Harland & Wolff Shipyard’s new Arrol Gantry. It was here that she and her sister, Titanic, were built side by side. T itanic‘s progress trailed some months in the Olympic‘s wake, and would enter service some time after Olympic. The Olympic was launched on October 20, 1910, and when she started down the ways, she became the largest moving object in the world. The Olympic – the world’s newest, largest and most luxurious ocean liner – made her maiden voyage on June 14, 1911. Aboard was J. Bruce Ismay, Chairman of the White Star Line and son of the Line’s founder. Also aboard was Harland & Wolff’s Thomas Andrews, nephew of Harland & Wolff’s Lord Pirrie. Captain Smith – who would go on to command the Titanic on her legendary and ill-fated maiden voyage the following year – was in command. The Olympic was so remarkable that by the time she had docked in New York, the formal order for the third entrant of the Olympic-class was placed. During the following ten months, the Olympic garnered the lion’s share of the fame on the Atlantic. Her sister Titanic was not given anywhere near the amount of attention, simply because she was the second of the class. Only after she sank did the Titanic eclipse the Olympic’s fame. Olympic made four round-trip voyages to New York and back to Southampton over the summer of 1911. Then, on September 20, 1911, she departed Southampton on what was to be her fifth west-bound crossing. As she proceeded toward the open sea, she encountered the HMS Hawke, a 360-foot long cruiser. The two vessels steamed side-by-side along a roughly parallel course, with the cruiser along the liner’s starboard side. At first, the smaller vessel was overtaking the Olympic, but then the Olympic‘s engine speed was increased, and the cruiser began to fall back. The suction from the larger ship’s propellers began to grow, and the Hawke was pulled bow-first into the starboard stern quarter of the Olympic. The Hawke‘s bow was crushed back, while the Olympic‘s hull was breached, and her two largest watertight compartments began to flood. Her crossing was canceled, and she limped back up to Belfast for repairs. The process kept her out of commission until the end of November. Once she returned to service, however, the Olympic proved that she was still a strong, reliable ship, even enduring severe punishment from the North Atlantic during a west-bound crossing to New York. On 9 October 1912, White Star withdrew Olympic from service and returned her to her builders at Belfast to have modifications added to incorporate lessons learned from the Titanic disaster six months prior, and improve safety. The number of lifeboats carried by Olympic was increased from twenty to sixty-eight, and extra davits were installed along the boat deck to accommodate them. An inner watertight skin was also constructed in the boiler and engine rooms, which created a double hull. On 4 August 1914, Britain entered the First World War. Olympic initially remained in commercial service under Captain Herbert James Haddock. As a wartime measure, Olympic was painted in a gray color scheme, portholes were blocked, and lights on deck were turned off to make the ship less visible. The schedule was hastily altered to terminate at Liverpool rather than Southampton, and this was later altered again to Glasgow. The first few wartime voyages were packed with Americans trapped in Europe, eager to return home, although the eastbound journeys carried few passengers. By mid-October, bookings had fallen sharply as the threat from German U-boats became increasingly serious, and White Star Line decided to withdraw Olympic from commercial service. After the War, the ship underwent a large-scale refurbishment at Harland & Wolff, which included her conversion to an oil-firing power plant. Then she was returned to commercial service. Throughout the 1920’s, she proved herself a solid, reliable vessel. But even the great Olympic could not survive the changing times. With the advent of newer, more modern-looking liners with more private bathrooms for their first class passengers, the Olympic began to look dated. When the Great Depression hit, this situation was made only worse as passenger bookings continued to decline. Nevertheless, the ship managed to help keep the White Star Line financially afloat. In 1934, the White Star Line merged with the Cunard Line at the instigation of the British government, to form Cunard White Star. This merger allowed funds to be granted for the completion of the future Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth. When completed, these two new ships would handle Cunard White Star’s express service; so their fleet of older liners became redundant and were gradually retired. After being laid up for five months alongside her former rival Mauretania, she was sold to Sir John Jarvis – Member of Parliament – for £97,500, to be partially demolished at Jarrow to provide work for the depressed region. On 11 October 1935, Olympic left Southampton for the last time and arrived in Jarrow two days later. The scrapping began after the ship’s fittings were auctioned off. Between 1935 and 1937, Olympic’s superstructure was demolished, and then on 19 September 1937, her hull was towed to Thos. W. Ward’s yard at Inverkeithing for final demolition which was finished by late 1937. At that time, the ship’s chief engineer commented, “I could understand the necessity if the ‘Old Lady’ had lost her efficiency, but the engines are as sound as they ever were”. By the time of her retirement, Olympic had completed 257 round trips across the Atlantic, transporting 430,000 passengers on her commercial voyages, traveling 1.8 million miles.

(Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / Flickr / AtlanticLiners.com). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe