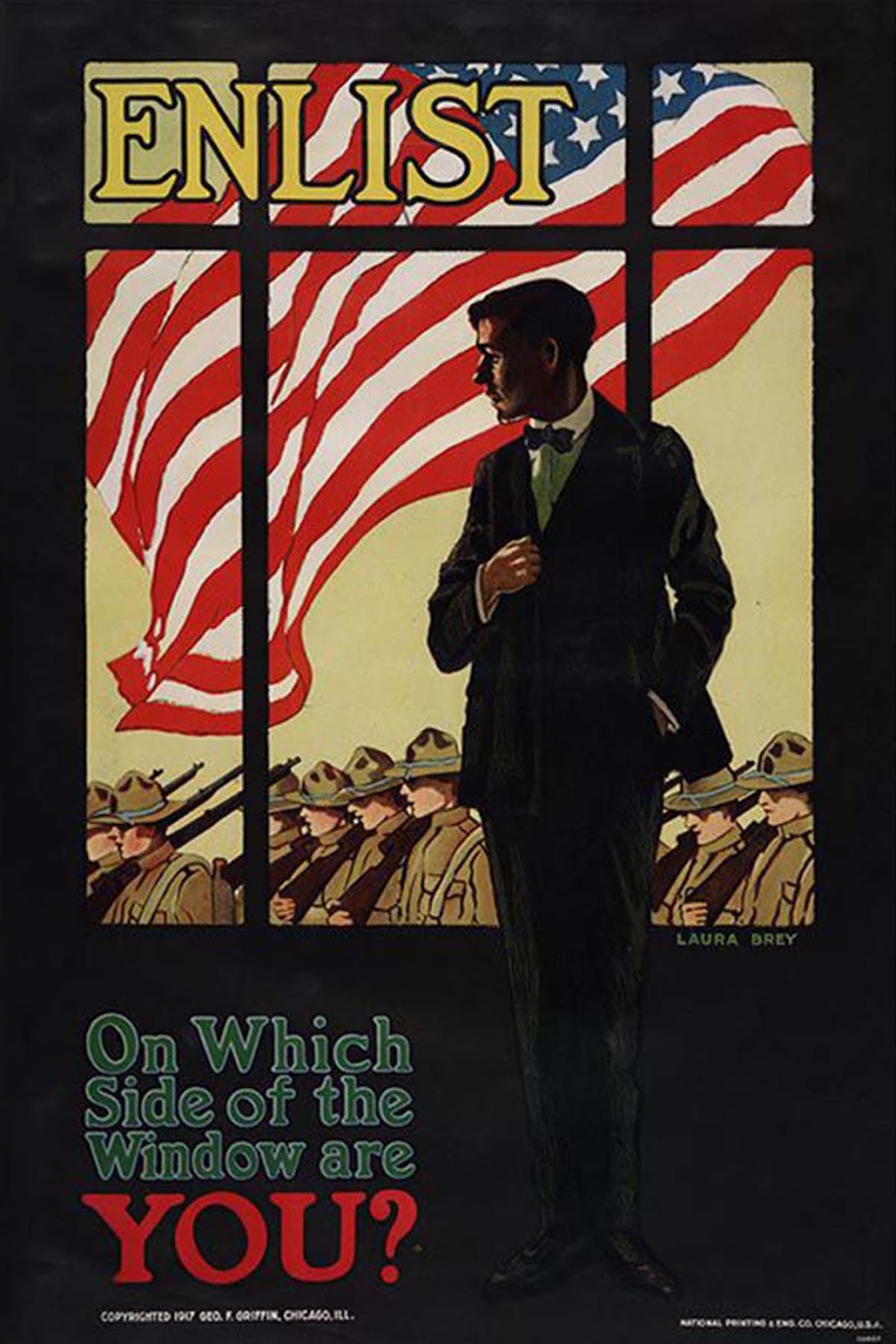

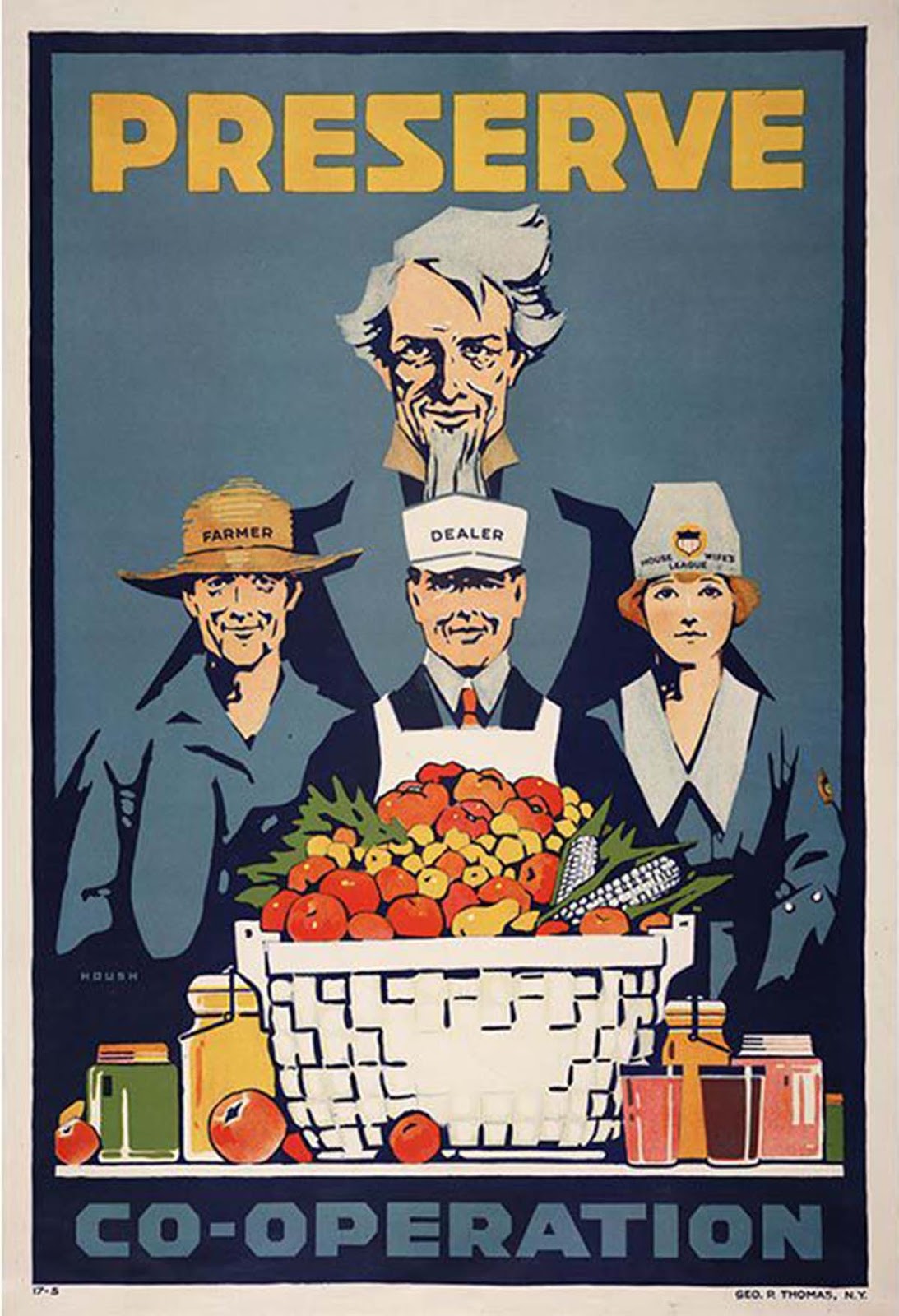

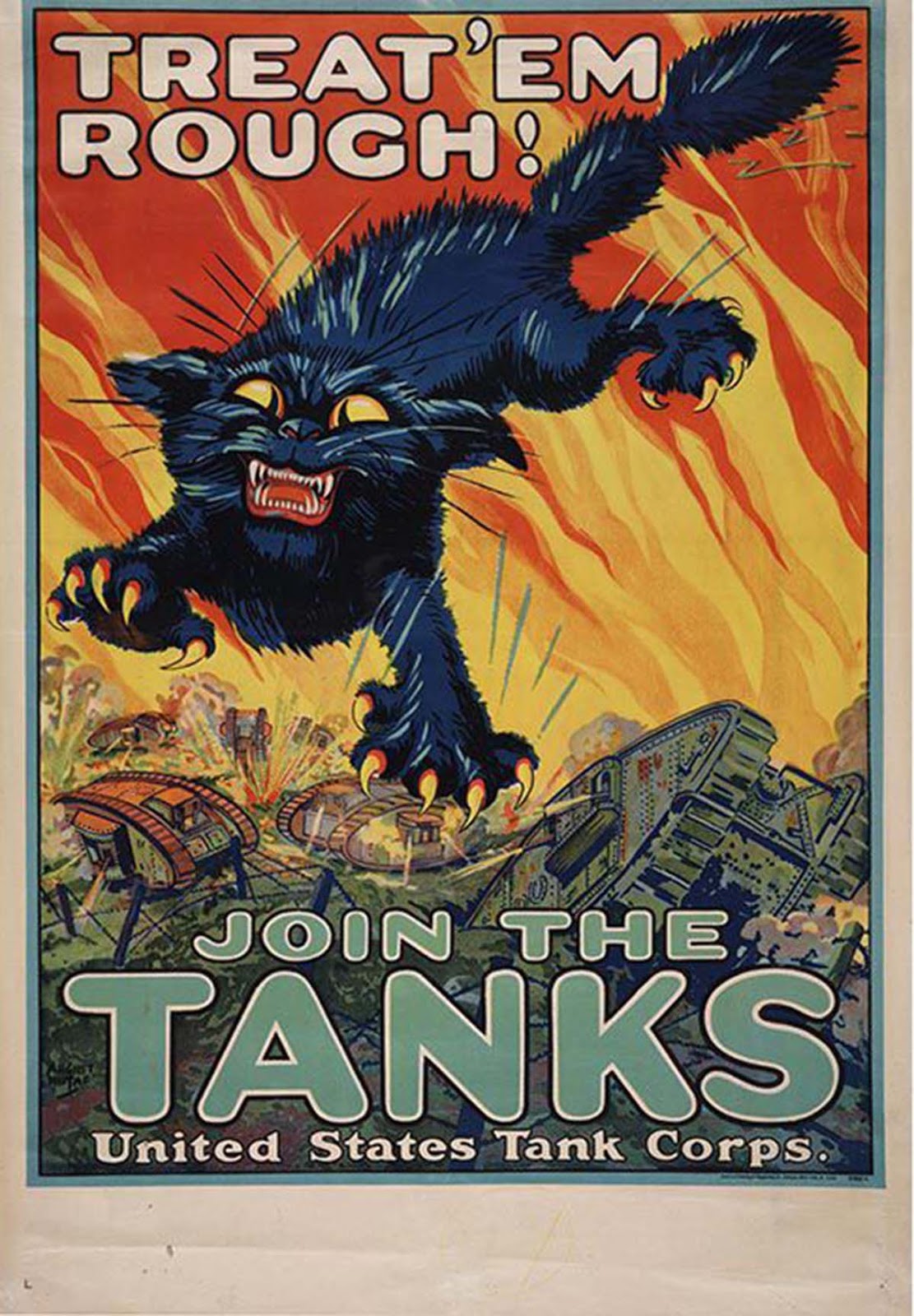

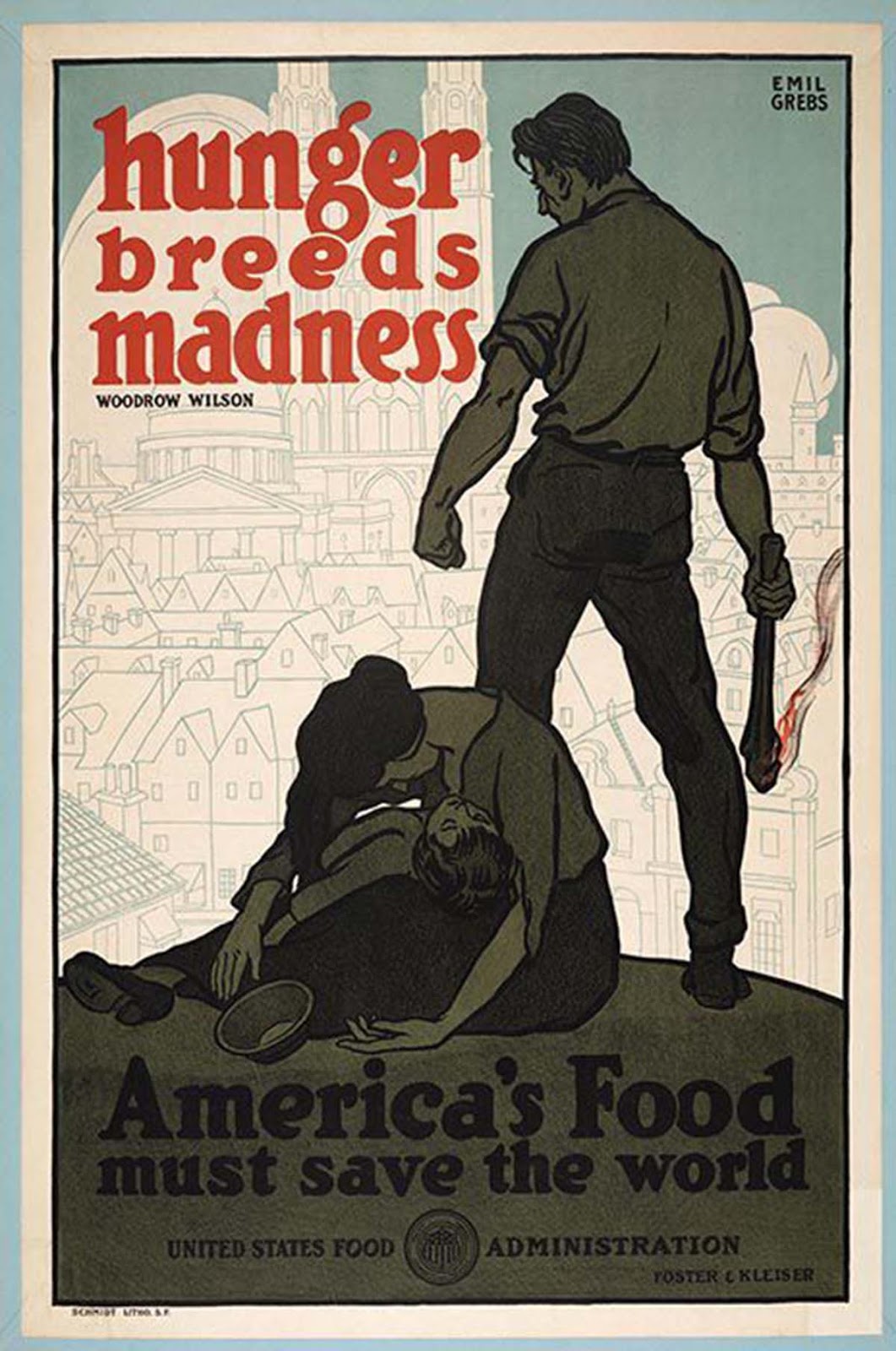

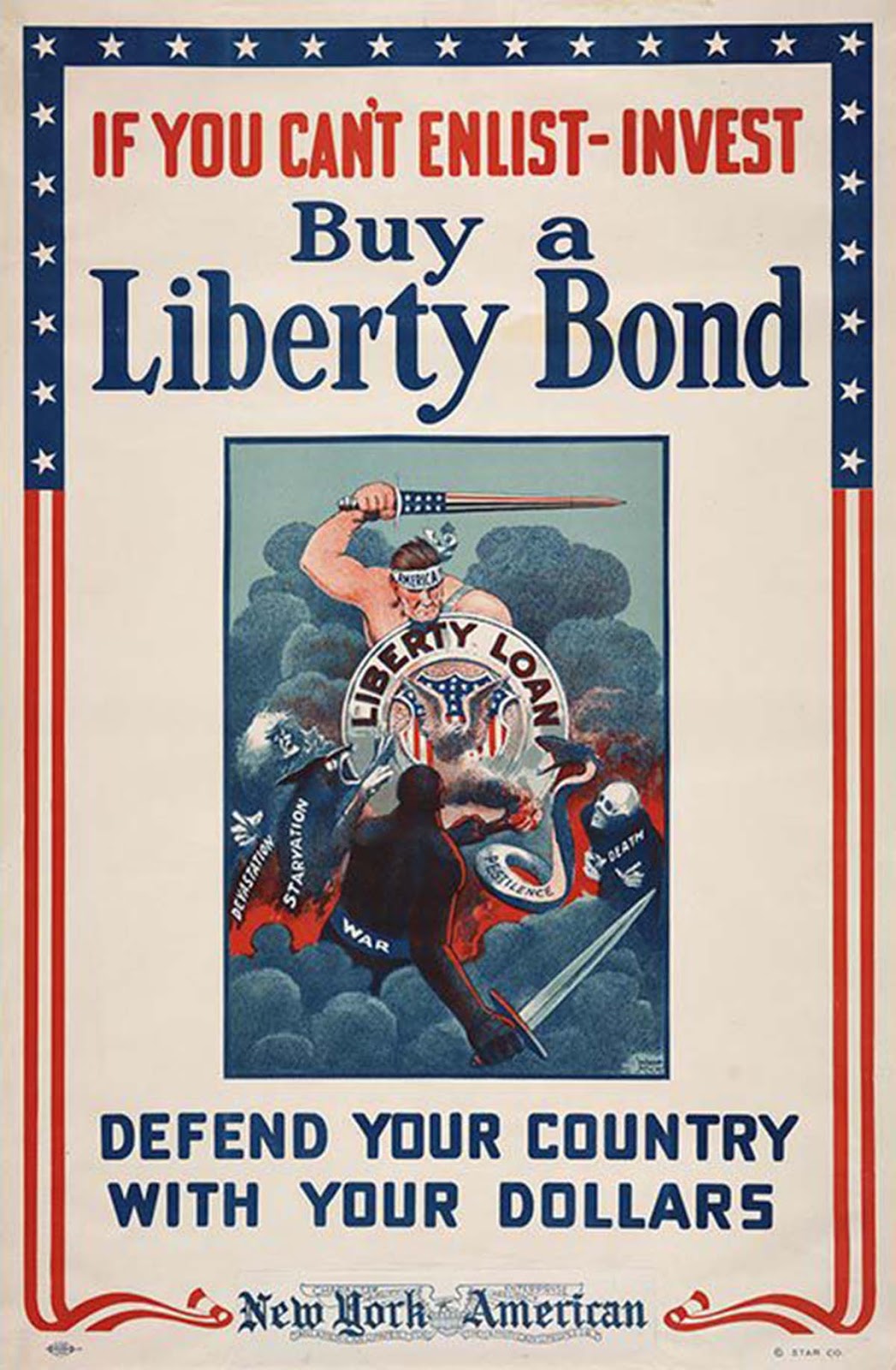

Such newly discovered technologies played an instrumental role in the shaping of the American mind and the altering of public opinion into a pro-war position. The government didn’t have time to waste while its citizens made up their minds about joining the fight. How could ordinary Americans be convinced to participate in the war “over there”? Posters—which were so well designed and illustrated that people collected and displayed them in fine art galleries—possessed both visual appeal and ease of reproduction. They could be pasted on the sides of buildings, put in the windows of homes, tacked up in workplaces, and resized to appear above cable car windows and in magazines. And they could easily be reprinted in a variety of languages. To merge this popular form of advertising with key messages about the war, the U.S. government’s public information committee formed a Division of Pictorial Publicity in 1917. The committee, headed by former investigative journalist George Creel, emphasized the message that America’s involvement in the war was entirely necessary in achieving the salvation of Europe from the German and enemy forces. In his book titled “How we Advertised America,” Creel states that the committee was called into existence to make World War I a fight that would be a “verdict for mankind”. He called the committee a voice that was created to plead the justice of America’s cause before the jury of public opinion. Creel also refers to the committee as a “vast enterprise in salesmenship” and “the world’s greatest adventure in advertising”. The committee’s message resonated deep within every American community and also served as an organization responsible for carrying the full message of American ideals to every corner of the civilized globe. (Photo credit: The Huntington Library). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe