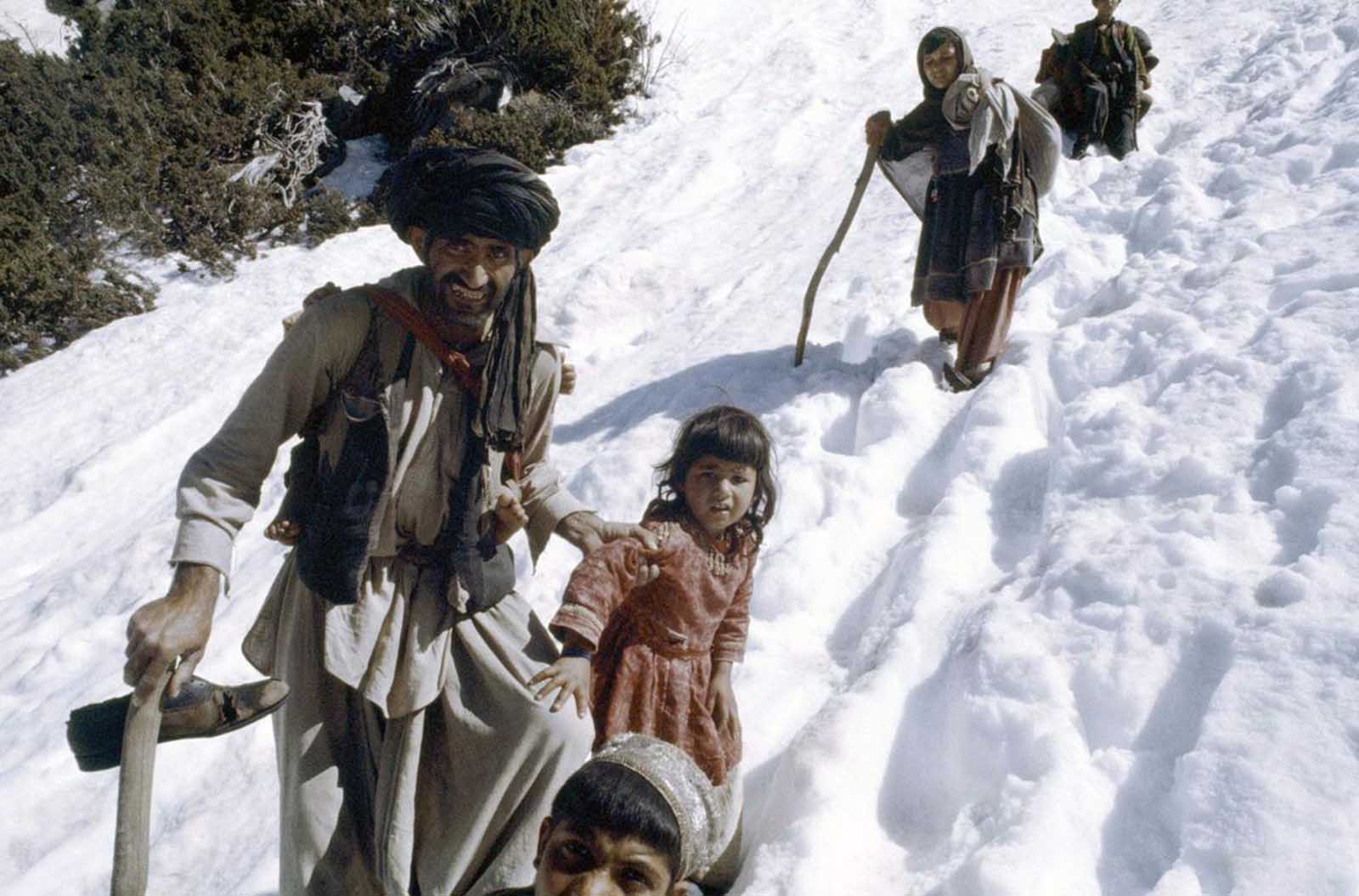

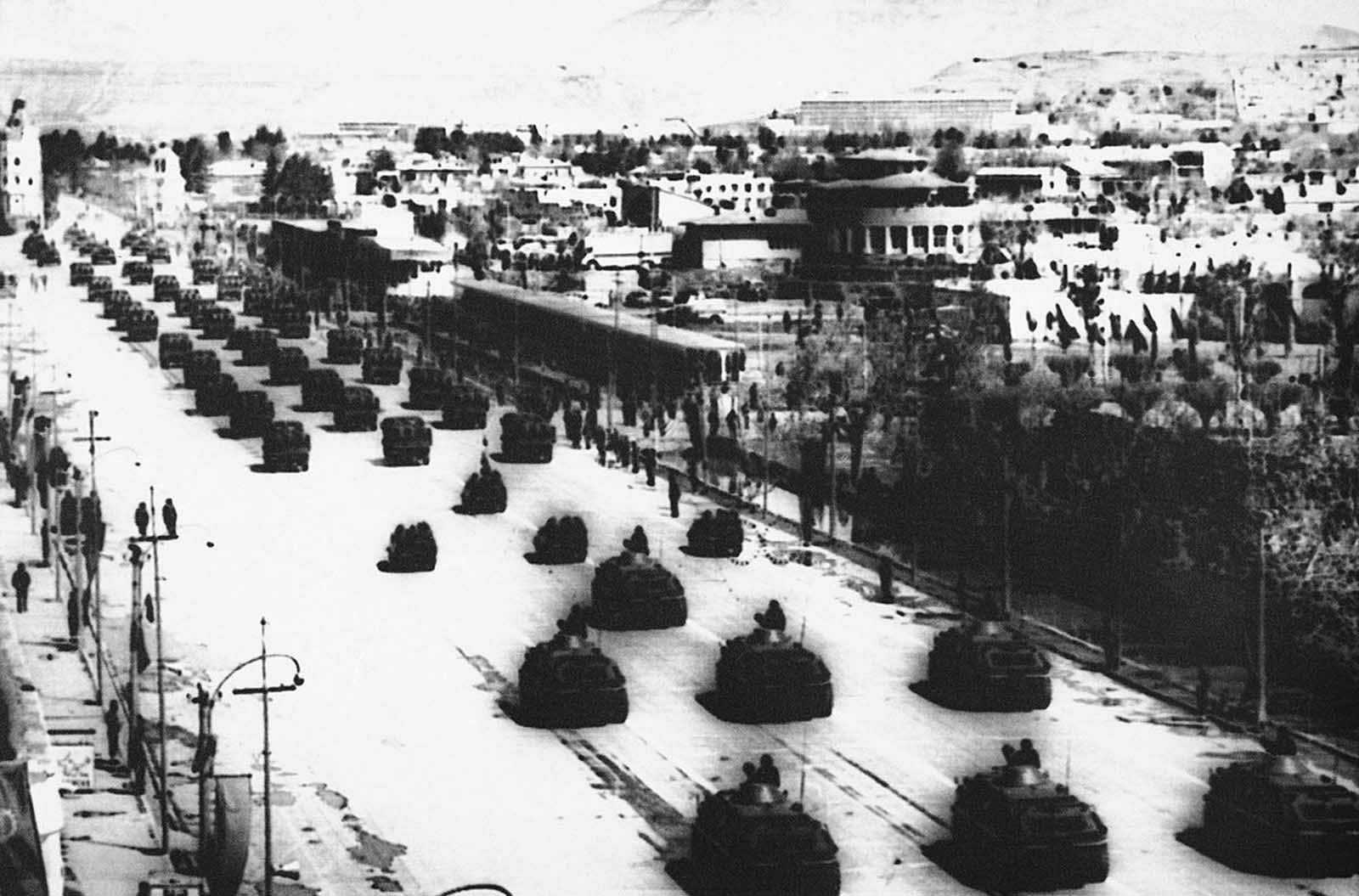

The Soviet Union supported the government while the rebels found support from a variety of sources including the United States (in the context of the Cold War) and Pakistan. The conflict was a proxy war between the two superpowers, who never actually met in direct confrontation. The actual reasons why the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan are far more complicated. The Soviet Union saw itself as being nearly entirely encircled by enemies. To the west stood Western Europe, which was filled with NATO forces, nuclear weapons, and American bases. To the Southeast was China, which had nearly a million troops along the border with the USSR. By this point, relations between China and the USSR were just awful, there were frequent deadly skirmishes across the Ussuri River, and China was openly working with the United States to contain the Soviet Union by 1979. To the South, they had American allies as well: Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Pakistan – capable of stationing American troops and missiles. The USSR did not understand the extent to which the Iranian revolution and a number of incidents with Pakistan had harmed relations with the United States, and still viewed them as being in lockstep with the US. Pretty much the only country on the Soviets’ southern border that didn’t have any real ties with the United States or China was Afghanistan. Afghanistan had some ties with the US and some ties with the USSR, but in both cases, they were fairly limited. The Afghan ties with the USSR included the training of Afghanistan’s elite class (military, political, scientific, etc) in Soviet universities, where they were indoctrinated in communism. This means that at the elite level, there were a lot of people who were coming to embrace a secular/communist ideology, while the general populace was strongly pro-Islam and tribal values. The elites, for example, were pro-women’s rights, while the general populace was in favor of traditional Afghan gender roles. In 1973 in Afghanistan, the King, Zahir Shah, was overthrown by his cousin, Daoud Khan. Daoud was not a communist by any means, but he did have ties to the communists, and he also had ties to Pashtun nationalist movements. This scared the Islamists in Afghanistan (who were becoming increasingly political thanks to the proliferation of texts from the Muslim Brotherhood and similar groups) and Pakistan, which was in a perpetual state of fear that ethnic conflicts could dissolve the state of Pakistan (this fear is not without purpose, Pakistan lost what is now Bangladesh to a civil war in 1971 that was fought largely on ethnic lines). India had assisted the Bangladeshis in the 1971 war, and India had ties to the USSR, so in Pakistan, which held itself together by the notion that it was an Islamic counterpart to India, there’s this perception that communism/USSR = secularism = ethnic fracturing = no more Pakistan. So Pakistan starts training and arming radical Islamists to go back into Afghanistan to fight against Daoud. By 1975 Daoud is dealing with this insurgency, but Daoud is a pretty masterful politician and he manages to keep the insurgents at bay, for the most part. The Islamists were still upset that Daoud is in power, but they really have two choices – either lay down their arms against him or flee to Pakistan. Plenty of them fled to Pakistan, which continued to arm and train them. The communist currents were getting out of control though, and Daoud was as scared of them as he was of the Islamists. Communism had infiltrated the military and political class, so Daoud was really in a difficult position. His campaigns against communism only served to push them further away from him, and in 1978 Daoud was killed by a radical communist named Taraki. If the Islamists were annoyed by Daoud, they were terrified at Taraki. Taraki was a hardcore communist and a serious reformer, and he was trying to implement reforms and build a Stalin-like police state and cult of personality at a rate the even the Soviets thought was too fast. They told him to slow down, but he just kept going and pretty much walked right into a civil war. Taraki’s crackdown on Islam, promotion of women’s rights, and just his overall reforms were too much for the Afghan populace, and in less than a year, by March of 1979, the country was pretty much in revolt against him. He was receiving aid from the USSR, and the insurgents were receiving aid from Pakistan, possibly Iran, and a little bit of aid from the US and possibly China. Most of that aid probably didn’t amount too much, but the Soviets viewed it the same way that any country would view it if they found out that a violent insurgency on their borders were being fueled by a foreign country. They blew it out of proportion and doubled down on Taraki. In August of 1979, it got even worse for the Soviets. Taraki’s foreign minister, who the Soviets did not like and were somewhat convinced was a CIA agent (he wasn’t) smothered Taraki with a pillow and took power for himself. With Taraki dead, the Soviets saw themselves as being completely strategically encircled. Following the opening of diplomatic relations between the United States and China, the Soviet Union now had to contend with the possibility of China’s enormous military population working to further pro-American and anti-Soviet strategic aims. The Chinese invasion of Vietnam in 1978 had proven that China was now willing to use force on a large scale to counter the Soviets and their allies. The revolution in Iran and the subsequent seizure of the American hostages had brought a buildup of American troops in the Indian Ocean, and the new regime in Iran was opposed to the Soviet Union almost as much as it was opposed to the United States. The Americans and NATO had enormous force on the USSR’s western flank, and were now preparing to station Pershing missiles in Western Europe. The Soviets likely underestimated the extent to which relations had been damaged between the United States and Pakistan, and were increasingly becoming convinced (correctly) that the two countries were working together to undermine the Soviet goals in Afghanistan. The incorrect assumption that those two were also working with Iran and China to undermine the Soviet Union only served as confirmation bias for the idea that the Soviet Union was being encircled. Only Afghanistan remained as a pro-Soviet buffer between the USSR and its enemies, and now the Soviet Union believed that their man in Afghanistan had been replaced by a CIA agent. The KGB begun to fear the potential for the deployment of Pershing missiles in Afghanistan, a direct threat to the Soviet’s southern underbelly—the part of the country most poorly equipped to detect and protect itself from missile and aerial attacks. The United States could then use the uranium deposits in Afghanistan to support Iranian and Pakistani drives toward nuclear weapons, further threatening the Soviet Union. The idea that the United States would be willing to support Iran’s Ayatollahs in the pursuit of a nuclear weapon may seem nonsensical, but it was a real possibility to the Kremlin in 1979. The situation in Afghanistan simply needed to be changed. So Soviets decided to invade. The initial Soviet deployment of the 40th Army in Afghanistan began on December 25, 1979. The Afghan War quickly settled down into a stalemate, with more than 100,000 Soviet troops controlling the cities, larger towns, and major garrisons and the mujahideen moving with relative freedom throughout the countryside. Soviet troops tried to crush the insurgency by various tactics, but the guerrillas generally eluded their attacks. The Soviets then attempted to eliminate the mujahideen’s civilian support by bombing and depopulating the rural areas. These tactics sparked a massive flight from the countryside; by 1982 some 2.8 million Afghans had sought asylum in Pakistan, and another 1.5 million had fled to Iran. The mujahideen were eventually able to neutralize Soviet air power through the use of shoulder-fired antiaircraft missiles supplied by the Soviet Union’s Cold War adversary, the United States. The mujahideen were fragmented politically into a handful of independent groups, and their military efforts remained uncoordinated throughout the war. The quality of their arms and combat organization gradually improved, however, owing to experience and to the large quantity of arms and other war matériel shipped to the rebels, via Pakistan, by the United States and other countries and by sympathetic Muslims from throughout the world. In addition, an indeterminate number of Muslim volunteers—popularly termed “Afghan-Arabs”, regardless of their ethnicity—traveled from all parts of the world to join the opposition. By mid-1987 the Soviet Union, now under reformist leader Mikhail Gorbachev, announced it would start withdrawing its forces. The final troop withdrawal started on May 15, 1988, and ended on February 15, 1989. Due to its length, it has sometimes been referred to as the “Soviet Union’s Vietnam War” or the “Bear Trap” by the Western media, and is thought to be a contributing factor to the fall of the Soviet Union. According to many scholars, the war contributed to the fall of the Soviet Union by undermining the image of the Red Army as invincible, undermining Soviet legitimacy, and by creating new forms of political participation. The war created a cleavage between the party and the military in the Soviet Union where the efficacy of using the Soviet military to maintain the USSR’s overseas interests was now put in doubt. In the non-Russian republics, those interested in independence were emboldened by the army’s defeat. In Russia the war created a cleavage between the party and the military, changing the perceptions of leaders about the ability to put down anti-Soviet resistance militarily (as it had in Czechoslovakia in 1968, Hungary in 1956, and East Germany in 1953). As the war was viewed as “a Russian war fought by non-Russians against Afghans”, outside of Russia it undermined the legitimacy of the Soviet Union as a trans-national political union. The war created new forms of political participation, in the form of new civil organizations of war veterans (Afghansti) which weakened the political hegemony of the communist party. It also started the transformation of the press/media which continued under glasnost. (Photo credit: AP Photo / Library of Congress / Russian Archives). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe