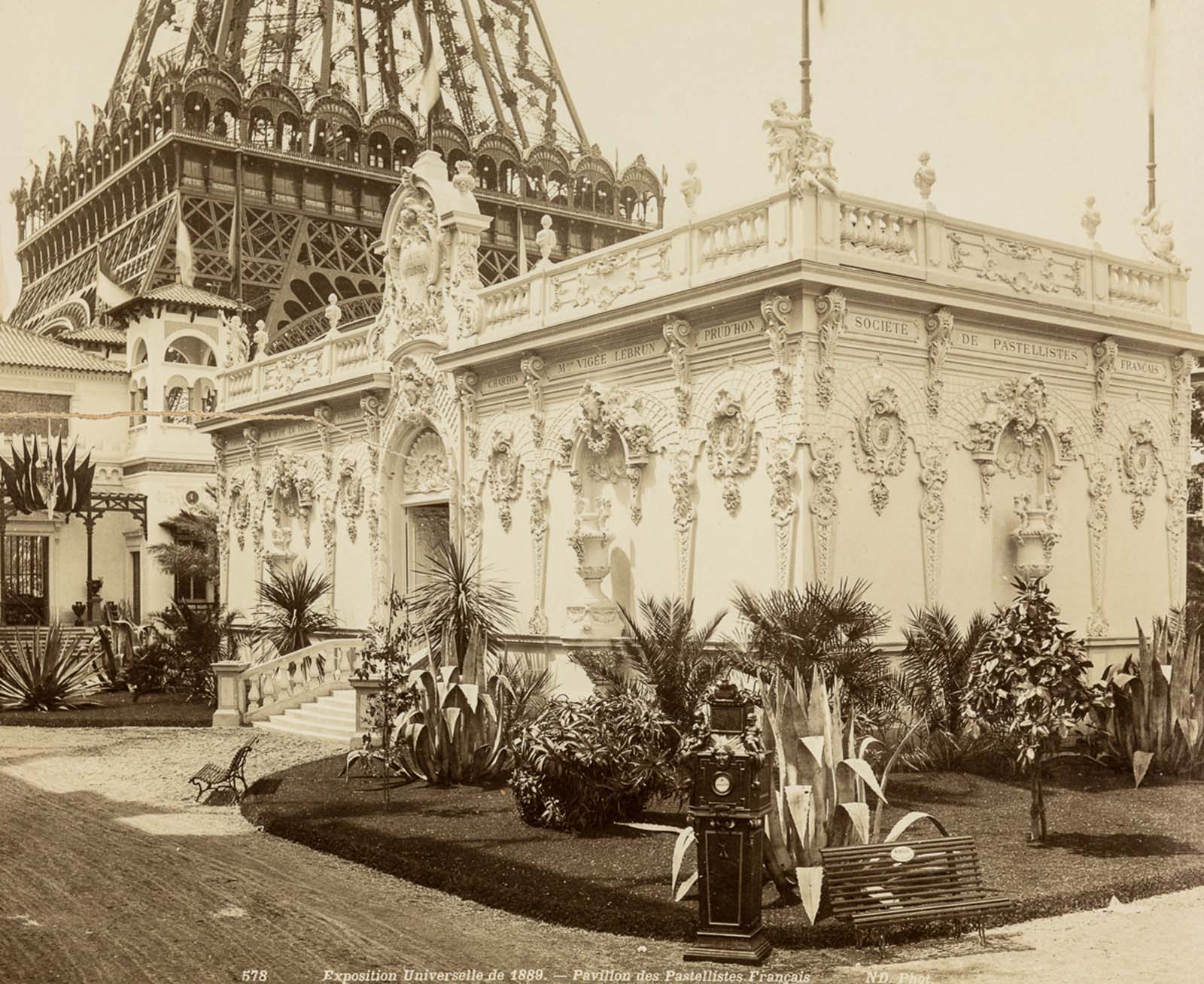

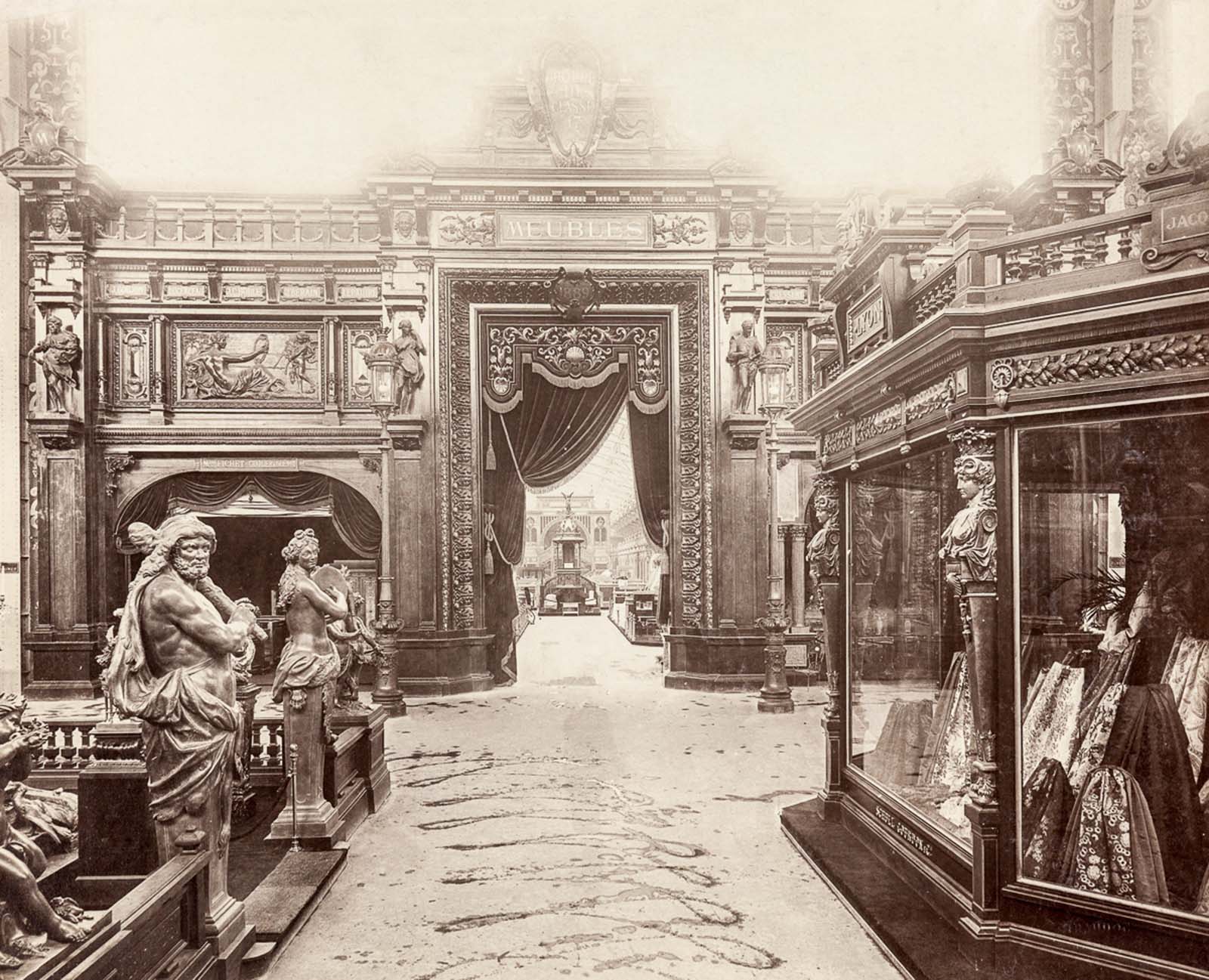

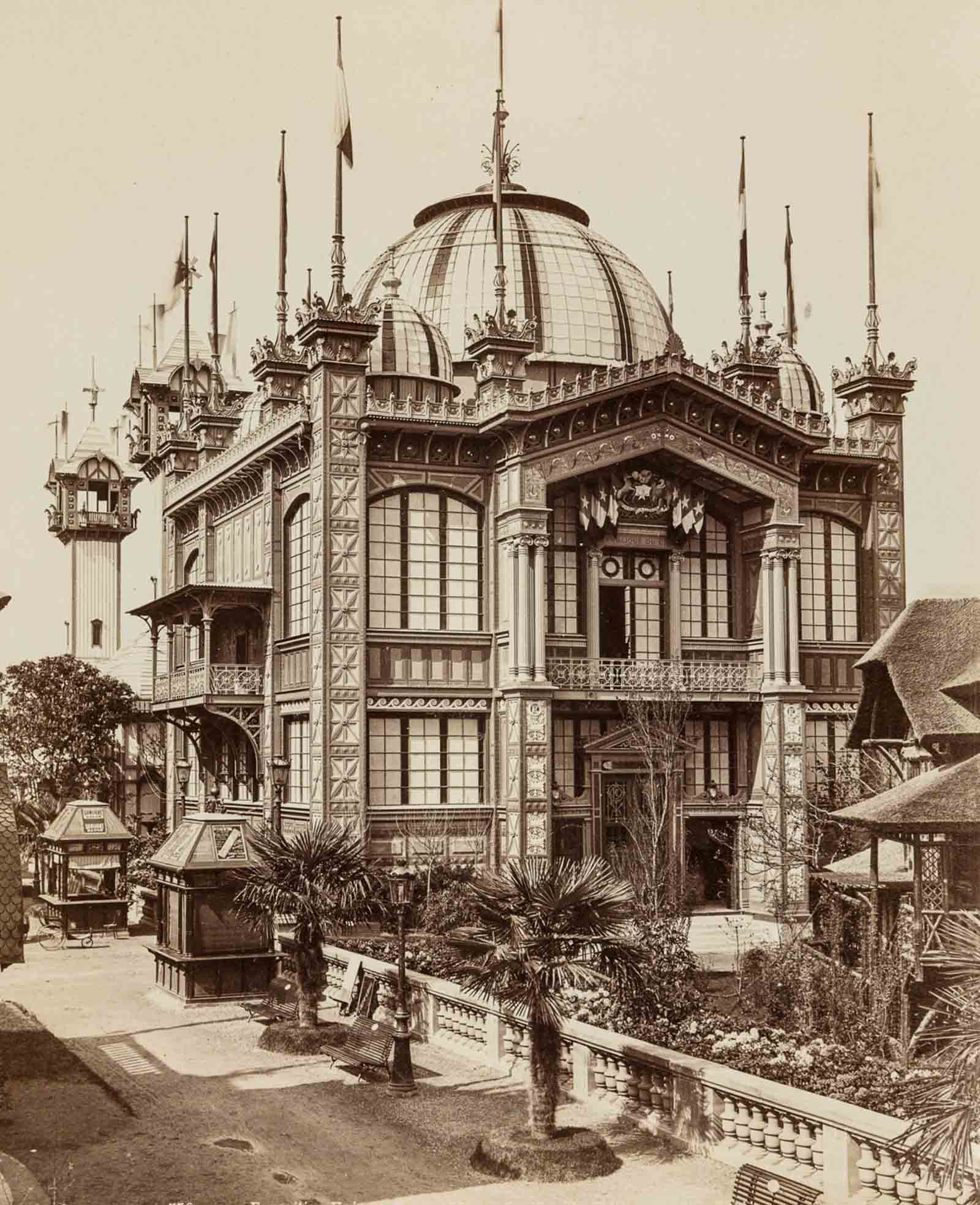

The 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle covered a total area of 0.96 km2, including the Champ de Mars, the Trocadéro, the quai d’Orsay, a part of the Seine, and the Invalides esplanade. Transport around the Exposition was partly provided by a 3 kilometer (1.9 mi) 600 millimeter (2 ft 0 in) gauge railway by Decauville. It was claimed that the railway carried 6.342.446 visitors in just six months of operation. The Fair had this time two sites: on the one hand, the Trocadéro and the Champ-de-Mars were housing the Fine Arts and industrial exhibits, as in 1878. On the other hand, east of the main site, the Esplanade des Invalides was housing a colonial exhibit, as well as several state-sponsored pavilions. There was, for instance, a hygiene “palace”, a public welfare pavilion, as well as a building dedicated to social economy. The state was therefore much more visible than in the previous fair. The Invalides site also had a very successful panorama called “Le panorama de tout-Paris”, which represented the capital’s social life. There were twenty-two different entrances to the Exposition, around its perimeter. They were open from 8 AM until 6:00 PM for the major exhibits and palaces, and until 11:00 in the evening for the illuminated greens and restaurants. The major ceremonial entrance was located at Les Invalides consisting of two tall pylons with colorful ornaments, like giant candelabras. Many buildings sprang up on the Champ de Mars, starting with the Eiffel Tower. A competition for the tower was launched by the state in 1884, which Gustave Eiffel won in 1886 over more than a hundred other candidates. Yet, the Tower was far from being unanimously praised. It was even very harshly criticized: the artists and writers of Paris protested against its erection in an official letter sent to the director of the Fair, calling it “unnecessary and monstrous.” On the shores of the Seine River, at the feet of the tower, an exhibit on the history of human dwelling was held in which the architect Charles Garnier (famous for the Opéra Garnier, commissioned by Napoleon III) participated extensively. The main halls of the fair were next to the Eiffel Tower on the Champ-de-Mars. The Palais des Beaux-arts and Palais des Arts Libéraux were both designed by the architect Joseph Bouvard. They stood right next to the Eiffel Tower. The two other main buildings were the Palais des expositions diverses (designed by Formigé) and the biggest building of all of them, the Galerie des machines (designed by Dutert). The Palais des arts libéraux contained exhibits on medicine, geography, teaching and pedagogy, music instruments, and photography, among many other things. The Palais des Beaux-arts housed many Naturalist paintings, but the impressionists remained largely ignored by the organization committee. Pre-Raphaelite painters such as Burne-Jones and Millais were also exhibited there. Behind these two buildings stood the Palais des expositions diverses, which housed exhibits of furniture, bronze casts, crystals, mosaics, clothes, and jewelry. The Palais des Machines was the last building on the Champ-de-Mars (it faced the École militaire, which still stands today). The building was technologically innovative: its size was very impressive, all the more since it had been built with as few roof supports as possible. This was made possible thanks to new progress in structural engineering. The Palais was made of steel and glass panels, and was about 375 feet long. One could visit the industry exhibit on the ground floor, but one could also see it from above by taking the moving platforms that were going back and forth from one end of the hall to another. These platforms (“ponts roulants”) also helped to build and dismantle the structure of the building before and after the Fair. The 1889 Paris World Fair was financially profitable to the state. Its scale was also much bigger than the preceding Fair: the surface occupied by the event was much larger than the previous fairs, and the number of exhibitors had also risen substantially. The number of visitors doubled compared to 1878, and the costs of 1889 were about the same as in 1878. The state made a profit of 8 000 000 francs, and acquired substantial real-estate in the process: the Eiffel Tower and the Palais des Machines both effectively belonged to the state, and the latter was to be used again for the 1900 World Fair. The countries which officially participated in the Exposition were Andorra, Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, the United States, Greece, Guatemala, Haiti, Hawaii, Honduras, India, Japan, Morocco, Mexico, Monaco, Nicaragua, Norway, Paraguay, Persia, Saint-Martin, El Salvador, Serbia, Siam, the Republic of South Africa, Switzerland, and Uruguay, The British dominions of New Zealand and Tasmania also took part. Because of the theme of the Exposition, celebrating the overthrow of the French monarchy, nearly all European countries with monarchies officially boycotted the Exposition. The boycotting nations were Germany, Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Spain, Great Britain, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Russia, and Sweden. Nonetheless, many citizens and companies from these countries did participate, and a number of countries had their participation entirely funded by private sponsors. (Photo credit: AALTO University / Brown University Library Center / L’Exposition de Paris, publiée avec la collaboration d’écrivains spéciaux, Vol. 1. Paris : Librairie illustrée, 1889). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe