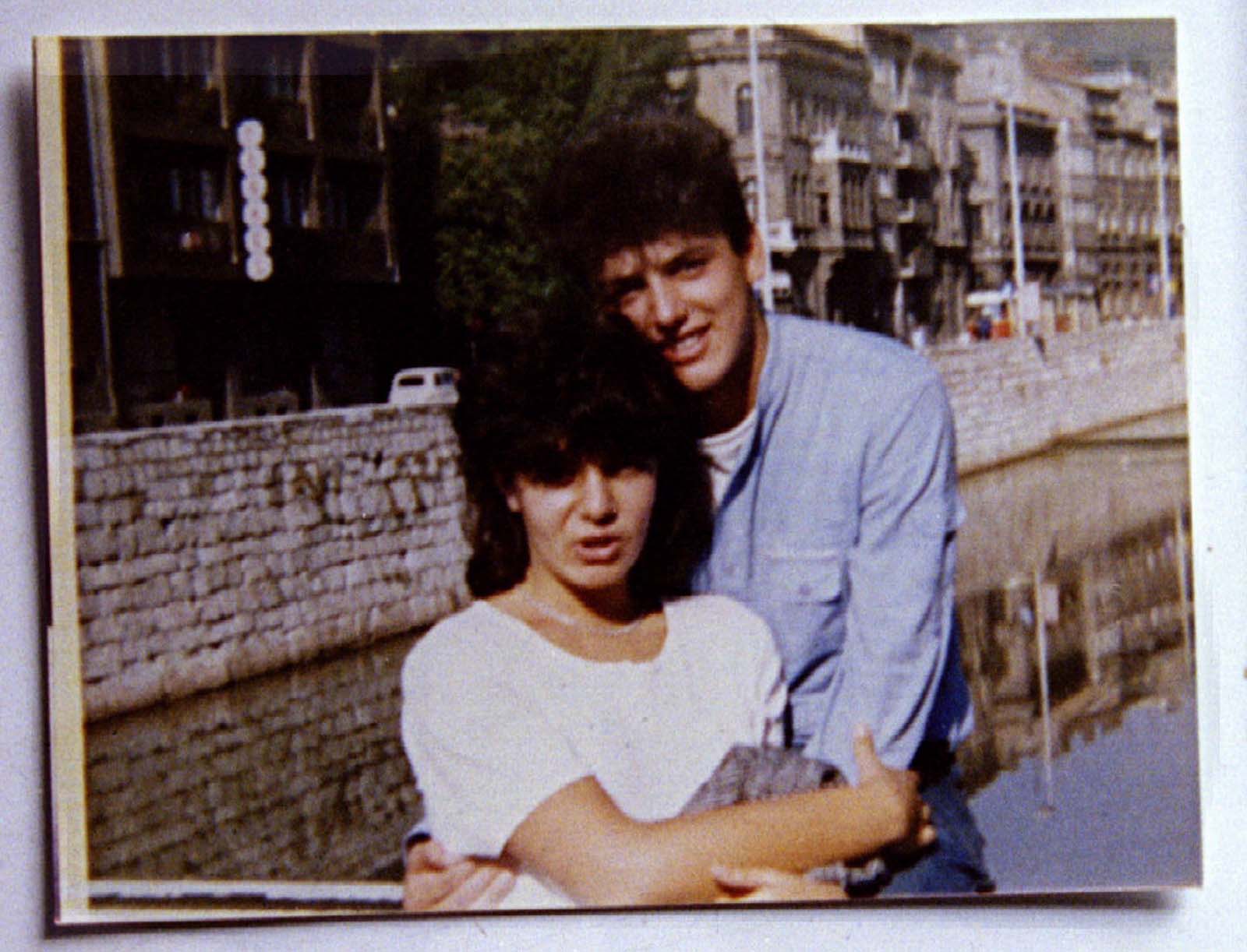

By the time they were finally removed from Sarajevo’s Vrbanja Bridge — still entwined — they had become symbols of enduring love caught in a senseless war. This is the story of Bosnia’s Romeo and Juliet. The Siege of Sarajevo (1992-1996), part of Yugoslavia’s Wars, was responsible for destroying lives, families, and the future of many residents. Nothing is more tragic than the story of childhood sweethearts Bosko Brkic and his girlfriend of nine years, Admira Ismic. What’s different about this love story is that he was a Bosnian Serb or Orthodox Christian, and she was a Bosniak Muslim. The two 25-year-olds had an unlikely love in the middle of an ethnic conflict. As the Siege became progressively worse, those who could escape, did. Bosko’s father died, and the rest of his family lived in Serbia. He could have escaped alone. He didn’t and chose to stay in Sarajevo with Admira until life got too hard. After living under siege for one year, the couple decided to escape to Bosko’s family. Bosnian Serbs had privileges. Muslims didn’t. They gathered together as much money as possible and made payments for their safe passage out of Sarajevo to safety via Grbavica, the Serb-held neighborhood. They would cross over the Miljacka River via the Vrbanja Bridge, or Sauda and Olga Bridge, named after the two anti-war protesters who were the first victims of the war on April 5, 1992. Everyone agreed no one would fire while they walked the bridge at 5:00 p.m. on May 19, 1993. On their fateful day, Bosko and Admira were optimistic. According to Dino Kapin, who was a Commander of a Croatian unit allied at the time with Bosnian Army forces, around 17:00 hours, a man and a woman were seen approaching the bridge. As soon as they were at the foot of the bridge, a shot was heard, and according to all sides involved in their passage, the bullet hit Boško Brkić and killed him instantly. Another shot was heard and the woman screamed, fell down wounded, but was not killed. She crawled over to her boyfriend, embraced him, hugged him, and died. It was observed that she was alive for at least 15 minutes after the shooting. Mark H. Milstein, the American photojournalist who made the haunting image of Admira and Boško, recalled in an interview that “the morning of May 19, 1993, had been pretty much a bust” for him as far as making photos were concerned: “After lunch, I hooked up with Japanese freelance TV cameraman and a Washington Times journalist. Together, we cruised the city looking for something different. Everywhere we went in Sarajevo ended in frustration. Before calling it a day, however, we decided to check out the front-line around the Vrbanja Bridge. There was a small battle going on, with Bosnian forces firing at a group of Serb soldiers near the ruins of the Union Invest building. Suddenly, a Serb tank appeared 200 meters in front of us and fired over our heads. We scrambled to the next apartment house and found ourselves holed up with a group of Bosnian soldiers. One of the soldiers yelled at me to look out the window, pointing at a young girl and boy running on the far side of the bridge. I grabbed my camera, but it was too late. The boy and girl were shot down. Bosnian Admira Ismić and Bosnian Serb Boško Brkić, both 25.” To this date, it is not known with certainty who fired the shots. The bodies of Admira and Boško laid on the bridge for days since no one dared to enter the Sniper Alley, a no man’s land, and recover them. As the bodies laid on the bridge, the Serbs and Bosnian armies argued over who killed the couple and who would ultimately take responsibility for the killing. After eight days, the bodies were recovered by Serb forces in the middle of the night and buried in Lukavica. However, it was later revealed that the Serb army forced Bosnian prisoners of war to go there in the middle of the night and recover the bodies. When the war was over, in 1996, on the initiative and the wish of Admira’s parents, their remains were transferred to the cemetery Lav in Sarajevo and they were buried together. Brkic’s mother Radmilla called the pair “a symbol of peace,” but rejected the comparison to Shakespeare’s masterpiece. Their love was never forbidden and the two families always respected each other. Admira’s parents were just as welcoming to Bosko. Whilst her grandmother was dubious that a mixed relationship could last, the general response of acceptance from both families encapsulates the wider and historical vision of Bosnia and Herzegovina. For much of its history, it had been a crossroads of nations, with Sarajevo serving as a cosmopolitan melting pot where Jewish, Muslim, Christian, Catholic, and Orthodox peoples lived together for 500 years. Many wrote about them, songs, articles, stories… One of the most famous articles was one from Kurt Shork, which was published by Reuters in May 1993 and it traveled around the world. Sarajevo’s group Zabranjeno Pusenje made a song a few years ago named Bosko i Admira, and also Bil Maden under the name Bosko and Admira. For many people in modern-day Bosnia, Ismic and Brkic’s story shows that only time will tell whether love or war will triumph in the long run. (Photo credit: Reuters / Mark H. Milstein). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe