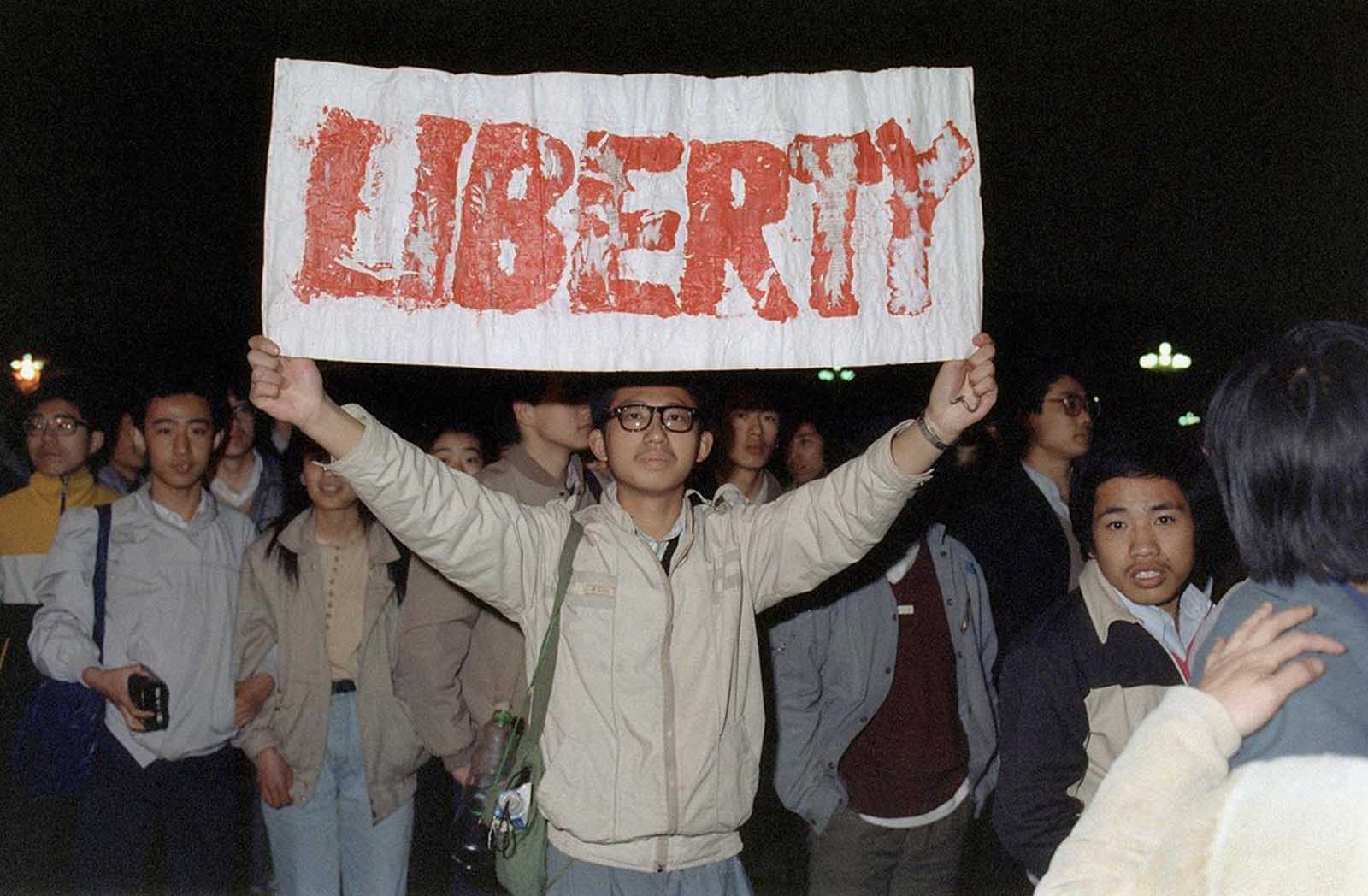

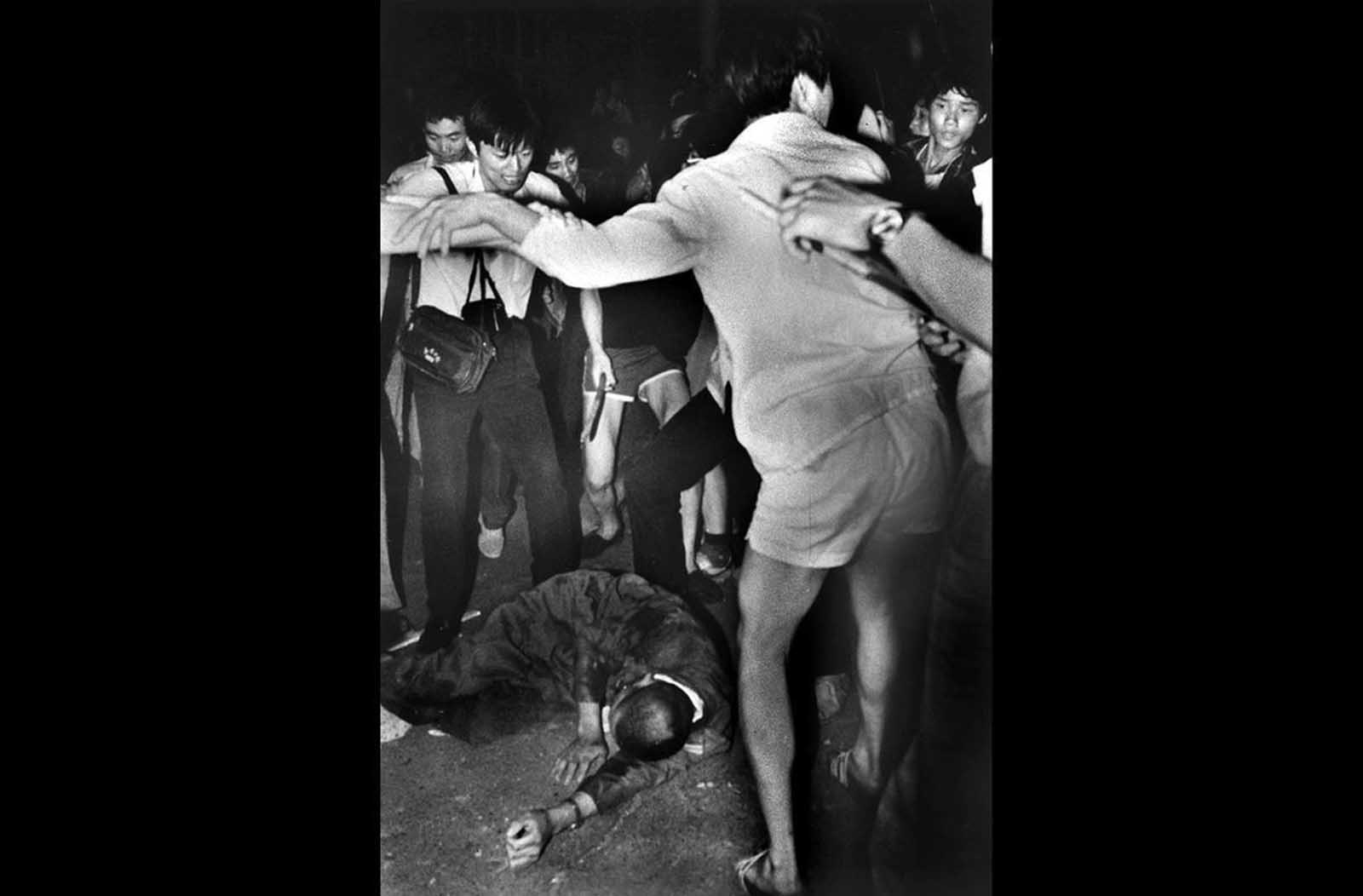

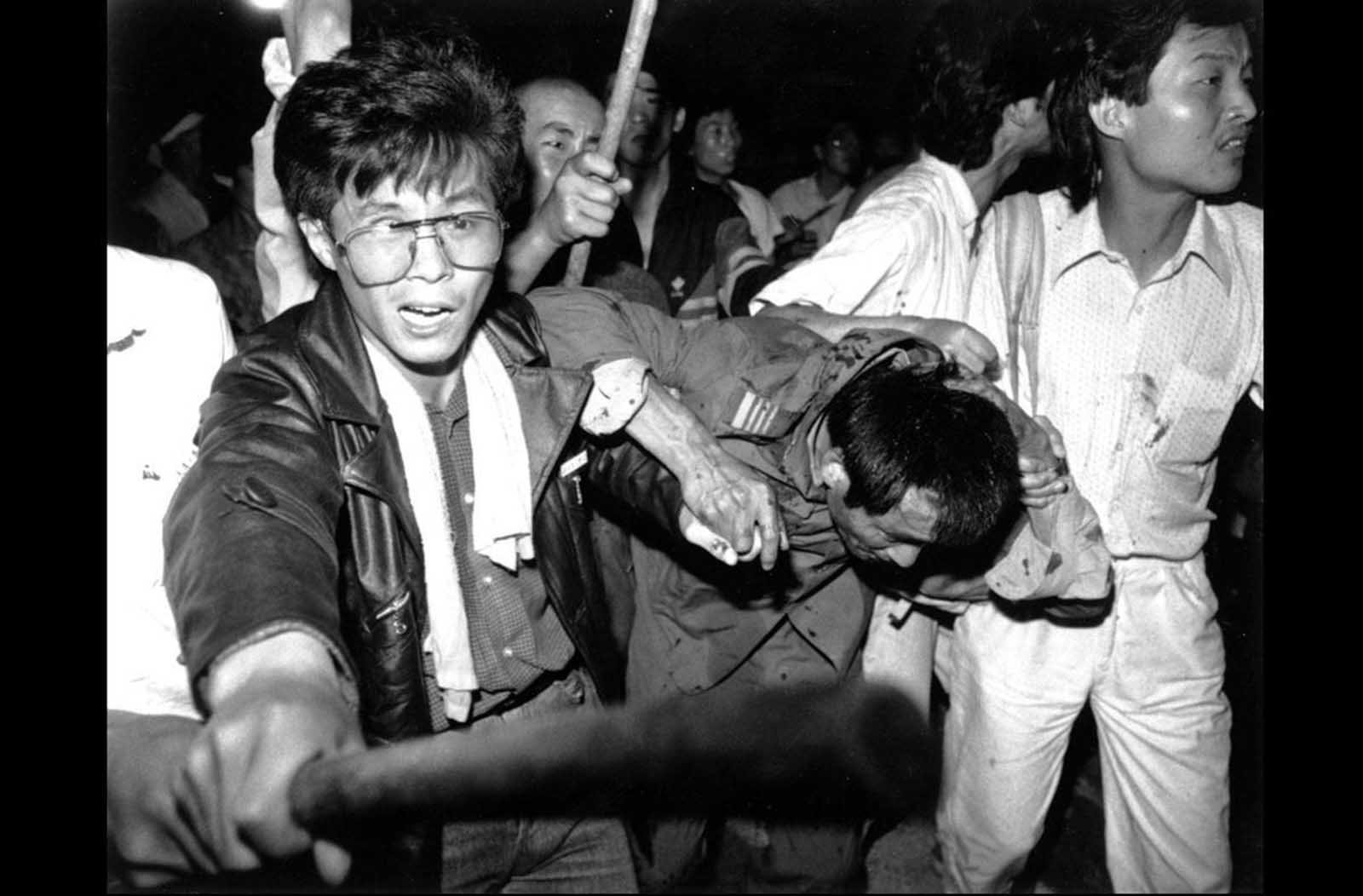

They were mainly led by Beijing students and intellectuals. The protests occurred in a year that saw the collapse of a number of communist governments around the world. By the spring of 1989, there was growing sentiment among university students and others in China for political and economic reform. The country had experienced a decade of remarkable economic growth and liberalization, and many Chinese had been exposed to foreign ideas and standards of living. In addition, although the economic advances in China had brought new prosperity to many citizens, it was accompanied by price inflation and opportunities for corruption by government officials. In the mid-1980s the central government had encouraged some people (notably scientists and intellectuals) to assume a more active political role, but student-led demonstrations calling for more individual rights and freedoms in late 1986 and early 1987 caused hard-liners in the government and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to suppress what they termed “bourgeois liberalism.” One casualty of this tougher stance was Hu Yaobang, who had been the CCP general secretary since 1980 and who had encouraged democratic reforms; in January 1987 he was forced to resign his post. The catalyst for the chain of events in the spring of 1989 was the death of Hu in mid-April; Hu was transformed into a martyr for the cause of political liberalization. On the day of his funeral (April 22), tens of thousands of students gathered in Tiananmen Square demanding democratic and other reforms. For the next several weeks, students in crowds of varying sizes—eventually joined by a wide variety of individuals seeking political, social, and economic reforms—gathered in the square. The initial government response was to issue stern warnings but take no action against the mounting crowds in the square. Similar demonstrations rose up in a number of other Chinese cities, notably Shanghai, Nanjing, Xi’an, Changsha, and Chengdu. However, the principal outside media coverage was in Beijing, in part because a large number of Western journalists had gathered there to report on the visit to China by Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in mid-May. Shortly after his arrival, a demonstration in Tiananmen Square drew some one million participants and was widely broadcast overseas. Meanwhile, an intense debate ensued among government and party officials on how to handle the mounting protests. Moderates, such as Zhao Ziyang (Hu Yaobang’s successor as party general secretary), advocated negotiating with the demonstrators and offering concessions. However, they were overruled by hard-liners led by Chinese premier Li Peng and supported by paramount elder statesman Deng Xiaoping, who, fearing anarchy, insisted on forcibly suppressing the protests. During the last two weeks of May, martial law was declared in Beijing, and army troops were stationed around the city. However, an attempt by the troops to reach Tiananmen Square was thwarted when Beijing citizens flooded the streets and blocked their way. Protesters remained in large numbers in Tiananmen Square, centering themselves around a plaster statue called “Goddess of Democracy,” near the northern end of the square. Western journalists also maintained a presence there, often providing live coverage of the events. By the beginning of June, the government was ready to act again. On the night of June 3–4, tanks and heavily armed troops advanced toward Tiananmen Square, opening fire on or crushing those who again tried to block their way. Once the soldiers reached the square, a number of the few thousand remaining demonstrators there chose to leave rather than face a continuation of the confrontation. By morning the area had been cleared of protesters, though sporadic shootings occurred throughout the day. The military also moved in forcibly against protesters in several other Chinese cities, including Chengdu, but in Shanghai, the mayor, Zhu Rongji (later to become the premier of China), was able to negotiate a peaceful settlement. By June 5 the military had secured complete control, though during the day there was a notable, widely reported incident involving a lone protester momentarily facing down a column of tanks as it advanced on him near the square. In the aftermath of the crackdown, the United States instituted economic and diplomatic sanctions for a time, and many other foreign governments criticized China’s handling of the protesters. The Western media quickly labeled the events of June 3–4 a “massacre.” The Chinese government arrested thousands of suspected dissidents; many of them received prison sentences of varying lengths of time, and a number were executed. However, several dissident leaders managed to escape from China and sought refuge in the West, notably Wu’er Kaixi. The disgraced Zhao Ziyang was soon replaced as party general secretary by Jiang Zemin and put under house arrest. From the outset of the incident, the Chinese government’s official stance was to downplay its significance, labeling the protesters “counterrevolutionaries” and minimizing the extent of the military’s actions on June 3–4. The government’s count of those killed was 241 (including soldiers), with some 7,000 wounded; most other estimates have put the death toll much higher. In the years since the incident, the government generally has attempted to suppress references to it. Public commemoration of the incident is officially banned. However, the residents of Hong Kong have held an annual vigil on the anniversary of the crackdown, even after Hong Kong reverted to the Chinese administration. The suppression on June 4 marked the end of a period of relative press freedom in China, and media workers—both foreign and domestic—faced heightened restrictions and punishment in the aftermath of the crackdown. State media reports in the immediate aftermath were sympathetic to the students. As a result, those responsible were all later removed from their posts. Two news anchors Xue Fei and Du Xian, who reported this event on June 4 in the daily Xinwen Lianbo broadcast on China Central Television were fired because they displayed sad emotions. Wu Xiaoyong, the son of former foreign minister Wu Xueqian was removed from the English Program Department of Chinese Radio International, ostensibly for his sympathies towards protesters. Editors and other staff at People’s Daily, including director Qian Liren and Editor-in-Chief Tan Wenrui, were also sacked because of reports in the paper that were sympathetic towards the protesters. Several editors were arrested. (Photo credit: National Archives / Library of Congress / AP). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe