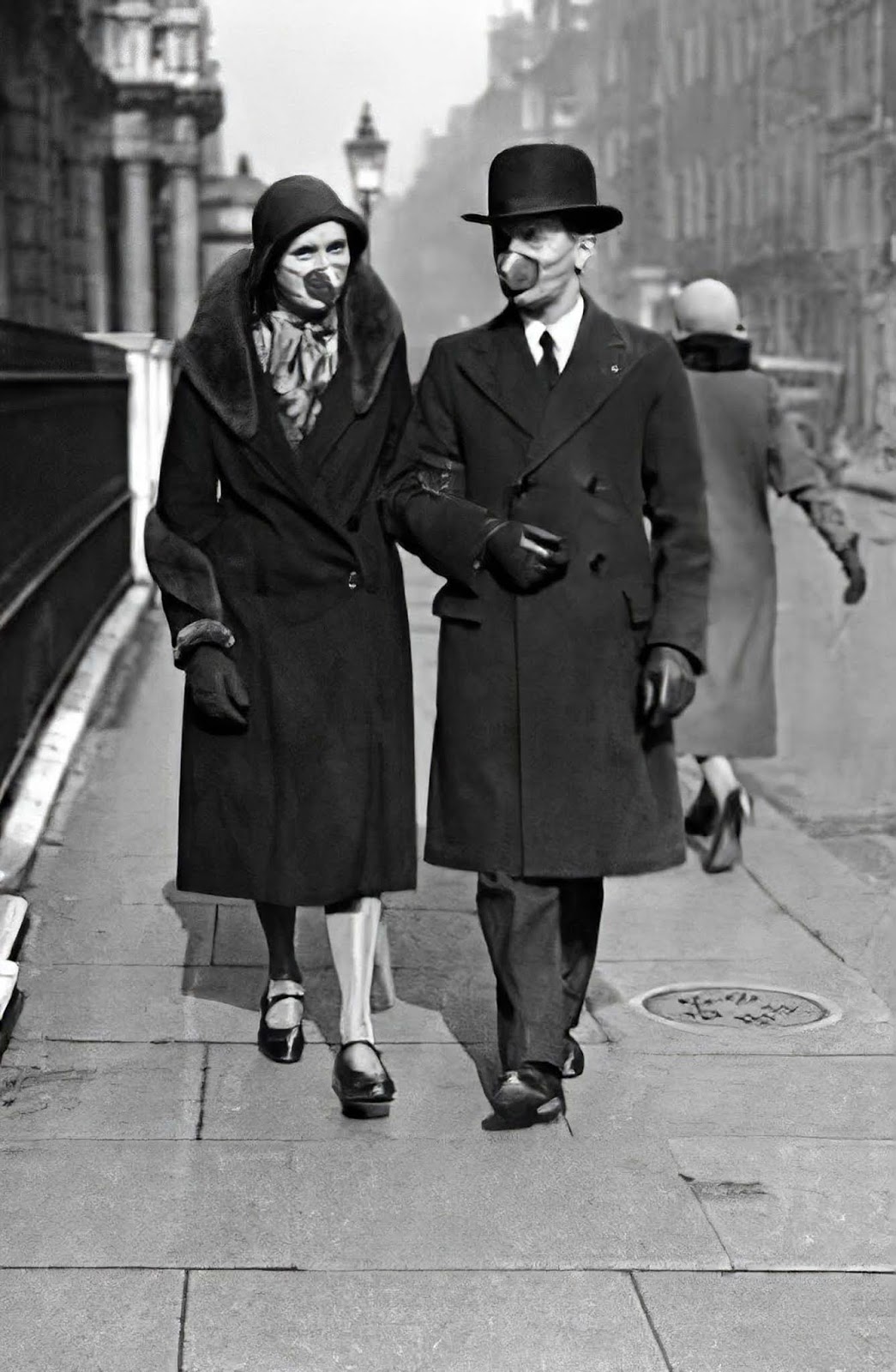

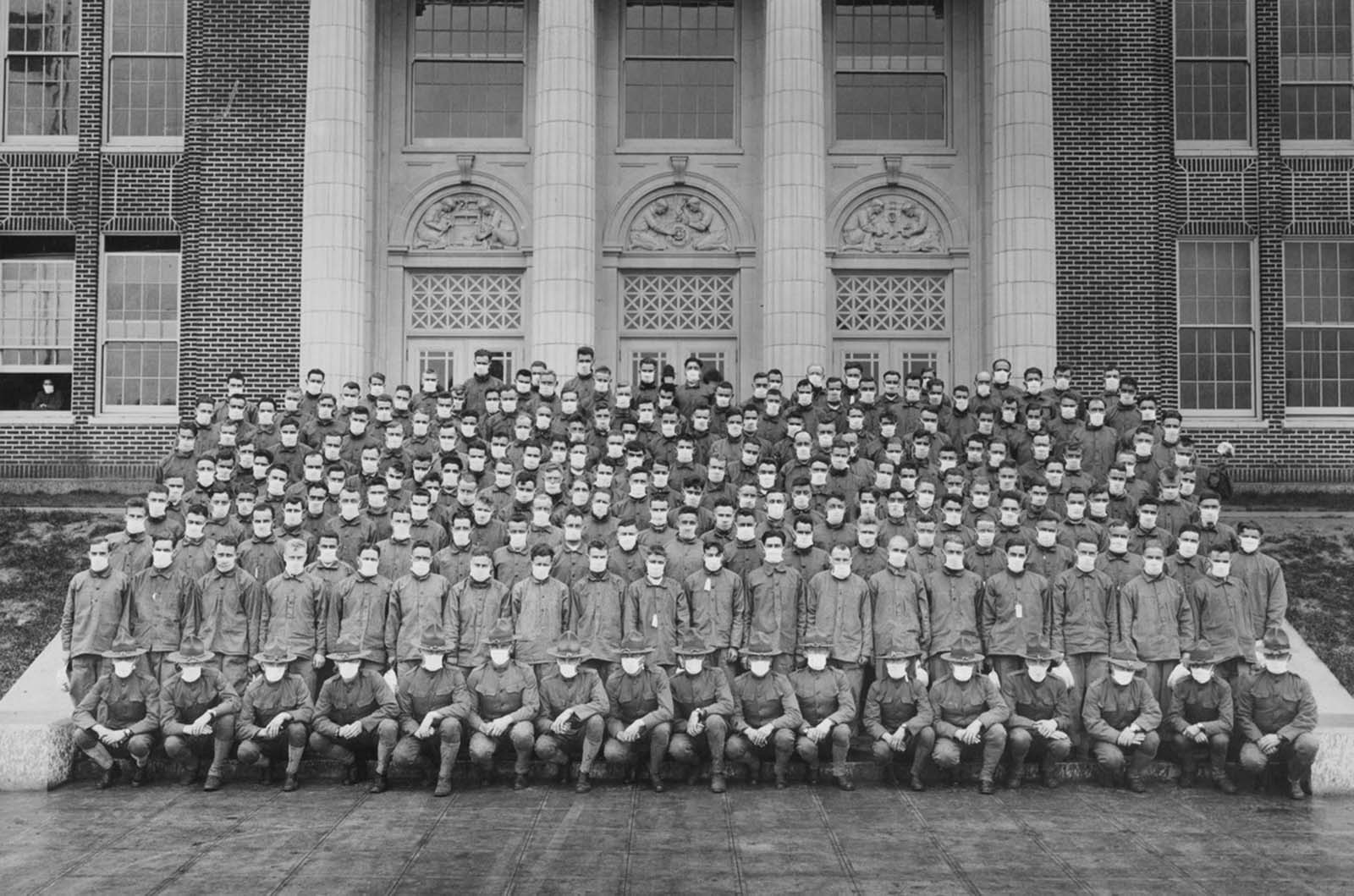

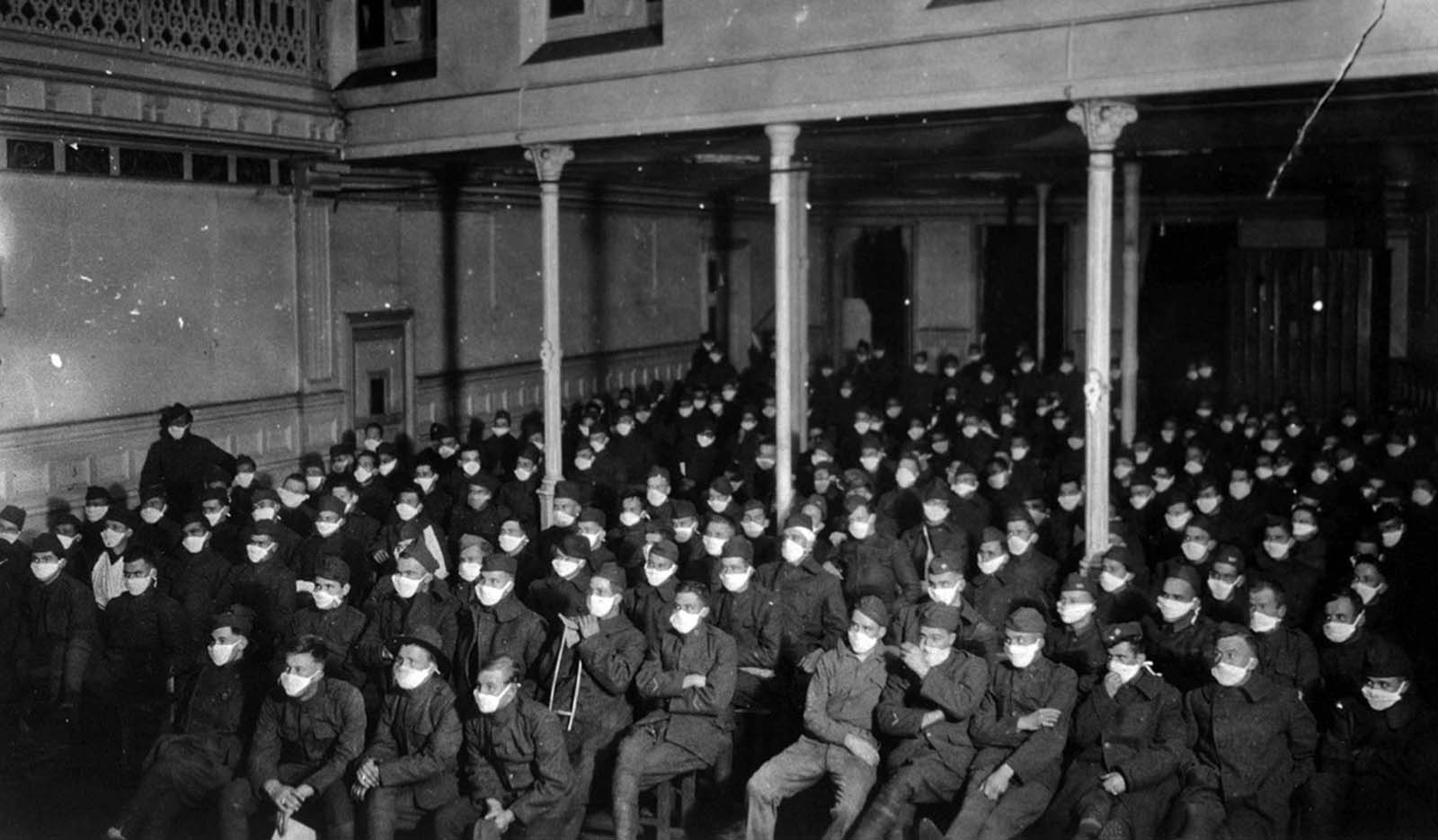

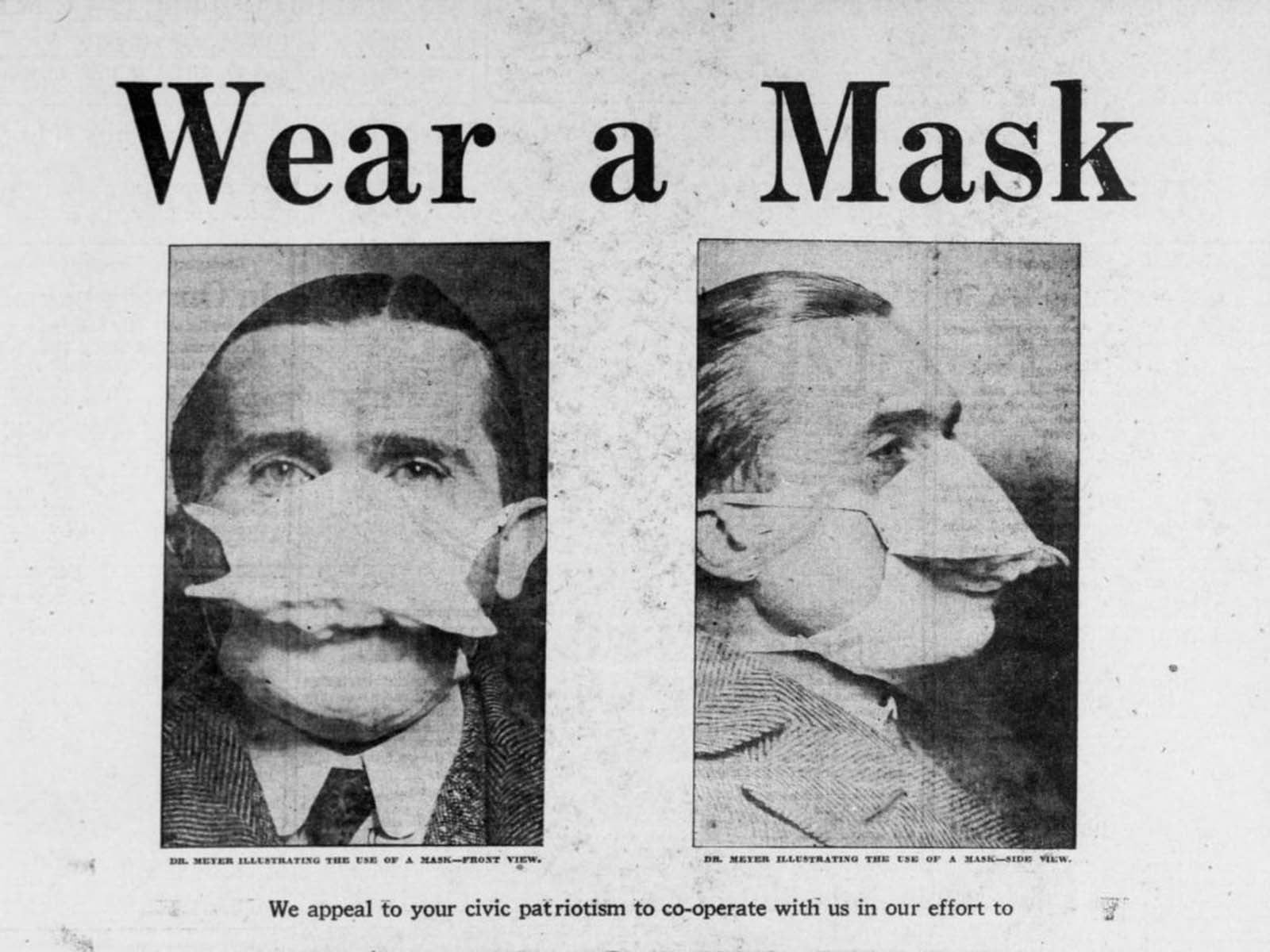

Newspapers provided instructions on “How to Make Masks at Home” and published photographs of masked nurses. Masks were just one of the “non-pharmaceutical interventions” or “social distancing” policies, to use modern terms, adopted to contain the epidemic, along with closing schools, prohibiting public gatherings, and advising changes in personal behavior. However, many people refused to wear them during the Spanish Flu of 1918, saying that government-mandated mask enforcement violated their civil liberties. An “Anti-Mask League” was even formed in San Francisco to protest the legislation. It turns out that men needed more convincing than did women to heed the advice of public health officials. Some men associated masks with femininity, and behaviors like spitting, careless coughing, and otherwise dismissal of hygiene made men the “weak links in hygienic discipline” during the 1918 pandemic, according to a 2010 report published in the US National Library of Medicine. For that reason, public health leaders rebranded personal care as a display of patriotism and duty to make men to wear masks. “The influenza pandemic offered a teaching moment in which masculine resistance to hygiene rules associated with mothers, schoolmarms, and Sunday school teachers could be replaced with a more modern, manly form of public health, steeped in discipline, patriotism, and personal responsibility,” reads the report. The transition from recommending masks for health care providers to encouraging and even requiring masks in public happened gradually and inconsistently. Most famously, San Francisco, California, along with other Western cities such as Seattle, Washington, Juneau, Alaska, and Phoenix, Arizona, passed laws requiring masks in public. Violators could be ticketed, fined, and imprisoned. Within weeks, however, as the number of cases and deaths decreased, recommendations and even regulations to wear masks were relaxed and then eliminated.

Did masks prevent the spread of the Spanish flu?

Experts reviewing evidence from 1918 concluded that flu masks failed to control infection. In December 1918, the American Public Health Association recommended that the “wearing of proper masks” should be compulsory for medical staff, occupations such as “barbers, dentists, etc.,” and “all who are directly exposed to infection.” The committee also found, however, that the evidence “as to beneficial results consequent on the enforced wearing of masks by the entire population at all times was contradictory,” and thus the committee did not recommend “the widespread adoption of this practice.” The committee did recommend that persons “who desire to wear masks” should be “instructed as to how to make and wear proper masks, and encouraged to do so.” In 1919, Wilfred Kellogg’s study for the California State Board of Health concluded that mask ordinances “applied forcibly to entire communities” did not decrease cases and deaths, as confirmed by comparisons of cities with widely divergent policies on masking. Masks were used most frequently out in public, where they were least effective, whereas masks were removed when people went inside to work or socialize, where they were most likely to be infected. Kellogg found the evidence persuasive: “The case against the mask as a measure of compulsory application for the control of epidemics appears to be complete.” In a comprehensive study published in 1921, Warren T. Vaughn declared “the efficacy of face masks is still open to question.” The problem was human behavior: Masks were used until they were filthy, worn in ways that offered little or no protection, and compulsory laws did not overcome the “failure of cooperation on the part of the public.” Vaughn’s sobering conclusion: “It is safe to say that the face mask as used was a failure.” In 1927, Edwin Jordan’s definitive study, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association as a series of articles and then as a book, determined that masks were effective when worn by patients already sick or by those directly exposed to victims, including nurses and physicians. Jordan also acknowledged, however, that “masks are uncomfortable and inconvenient, as anyone who has worn them can testify” and require a great deal of “discipline, self-imposed or other.” Jordan came to a more guarded conclusion: “The effect of mask-wearing throughout the general community is not easy to determine.”

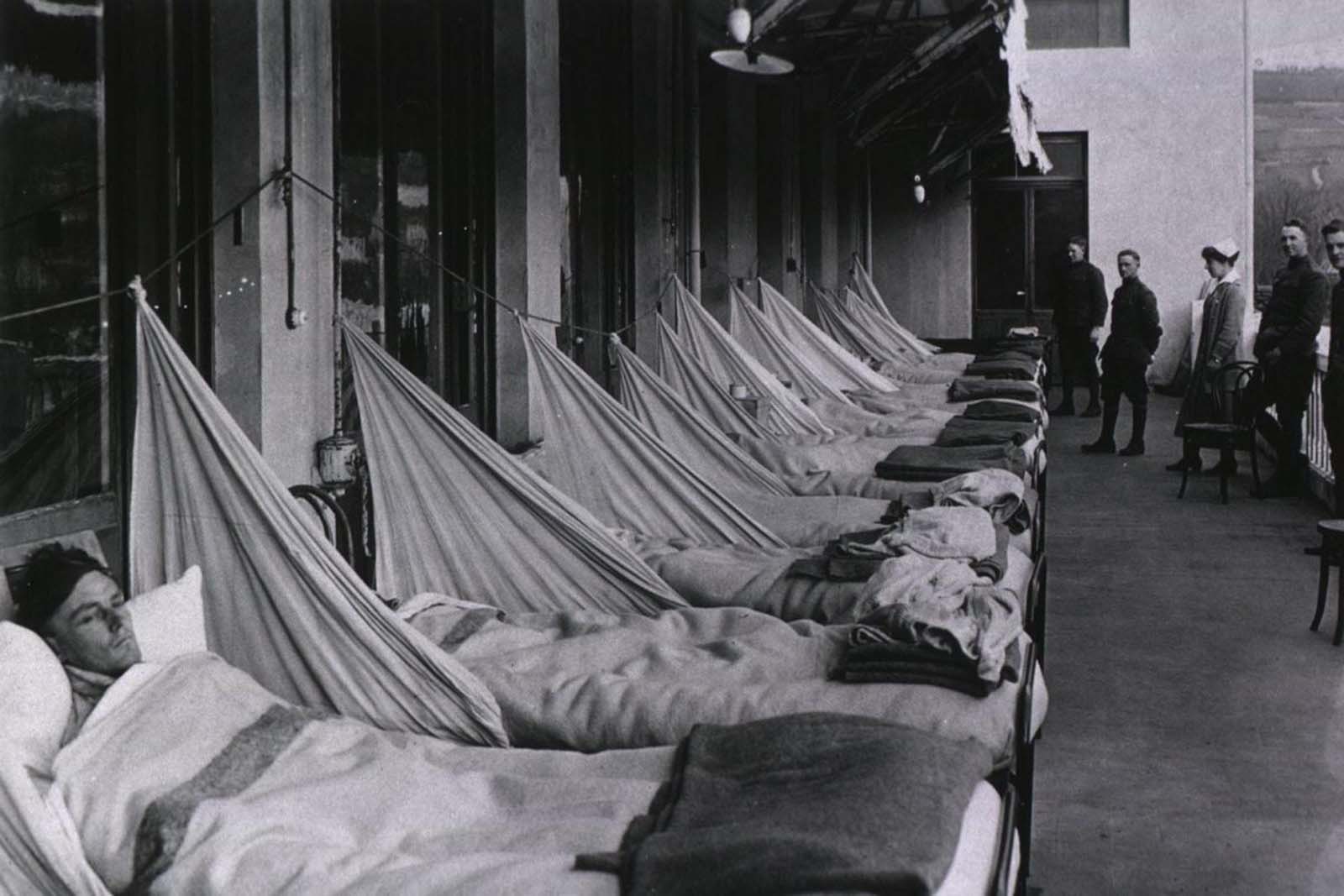

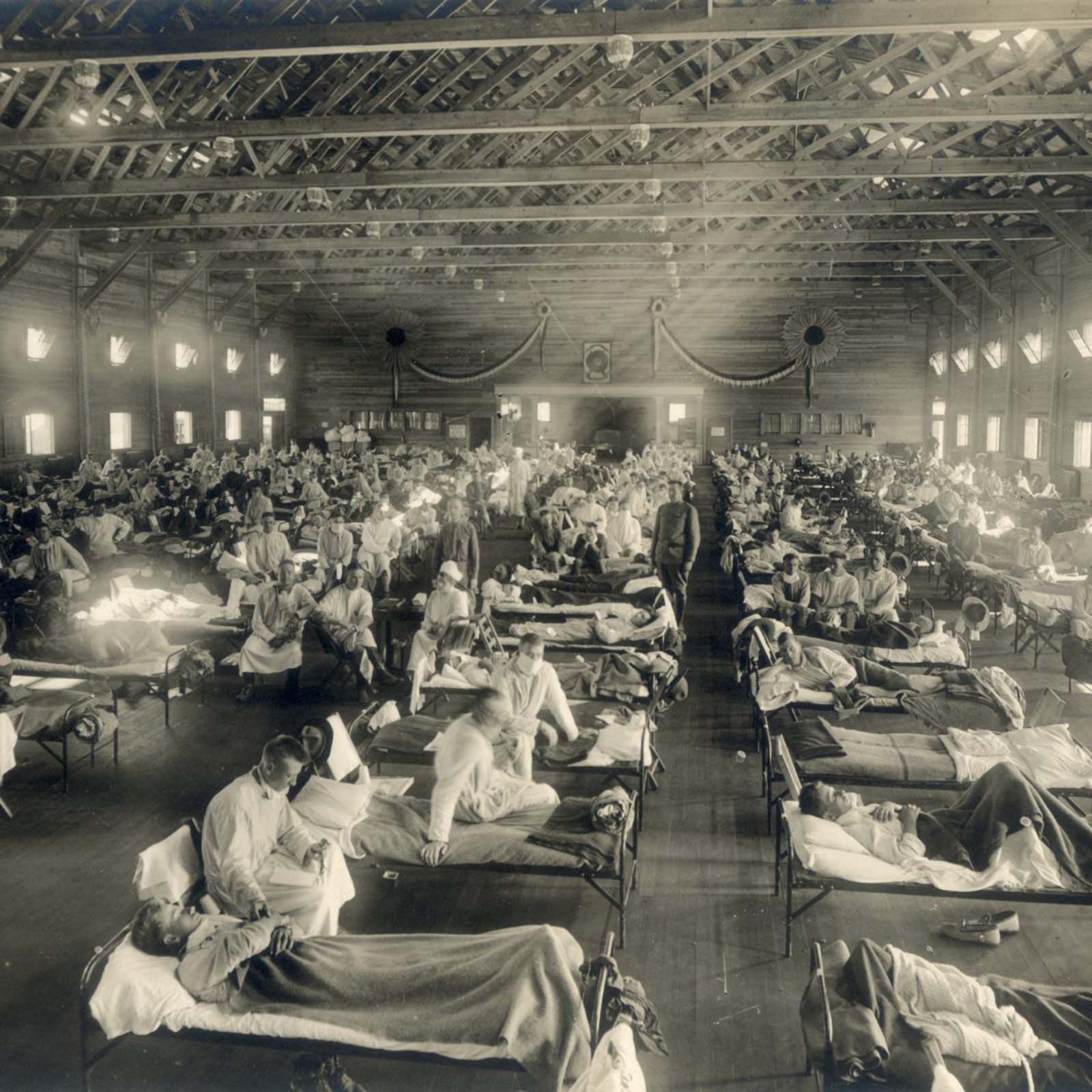

The Mortality of the Spanish Flu

The Spanish flu infected around 500 million people, about one-third of the world’s population. Estimates as to how many infected people died vary greatly, but the flu is regardless considered to be one of the deadliest pandemics in history. An estimate from 1991 states that the virus killed between 25 and 39 million people. A 2005 estimate put the death toll at 50 million (about 3% of the global population), and possibly as high as 100 million (more than 5%). However, a reassessment in 2018 estimated the total to be about 17 million, though this has been contested. With a world population of 1.8 to 1.9 billion, these estimates correspond to between 1 and 6 percent of the population. (Photo credit: The LIFE Images Collection / U.S. National Library of Medicine / National Archives / Atlantic Magazine / Text: “Flu Masks Failed In 1918, But We Need Them Now, ” Health Affairs Blog, May 12, 2020. / Business Insider). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe