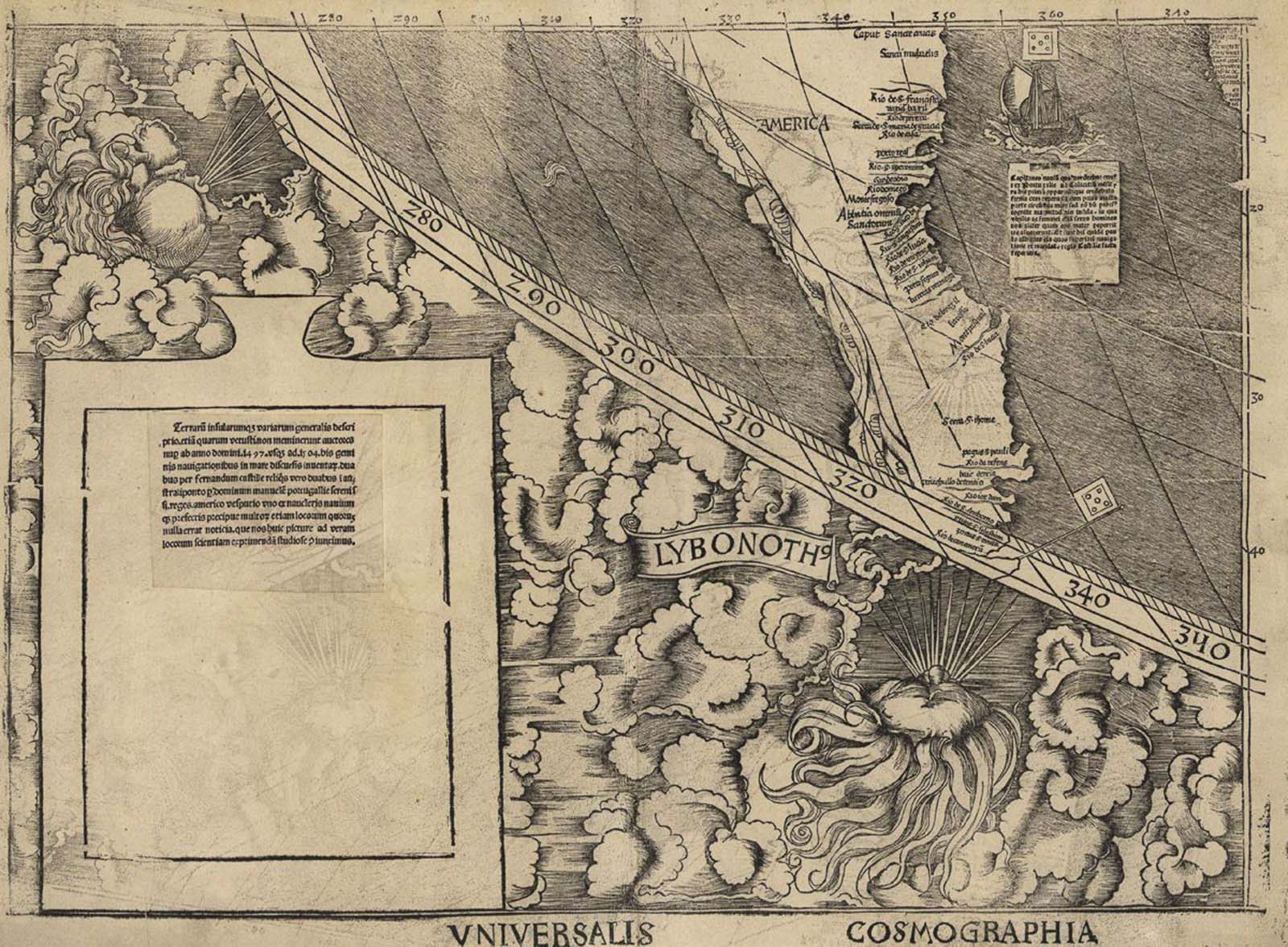

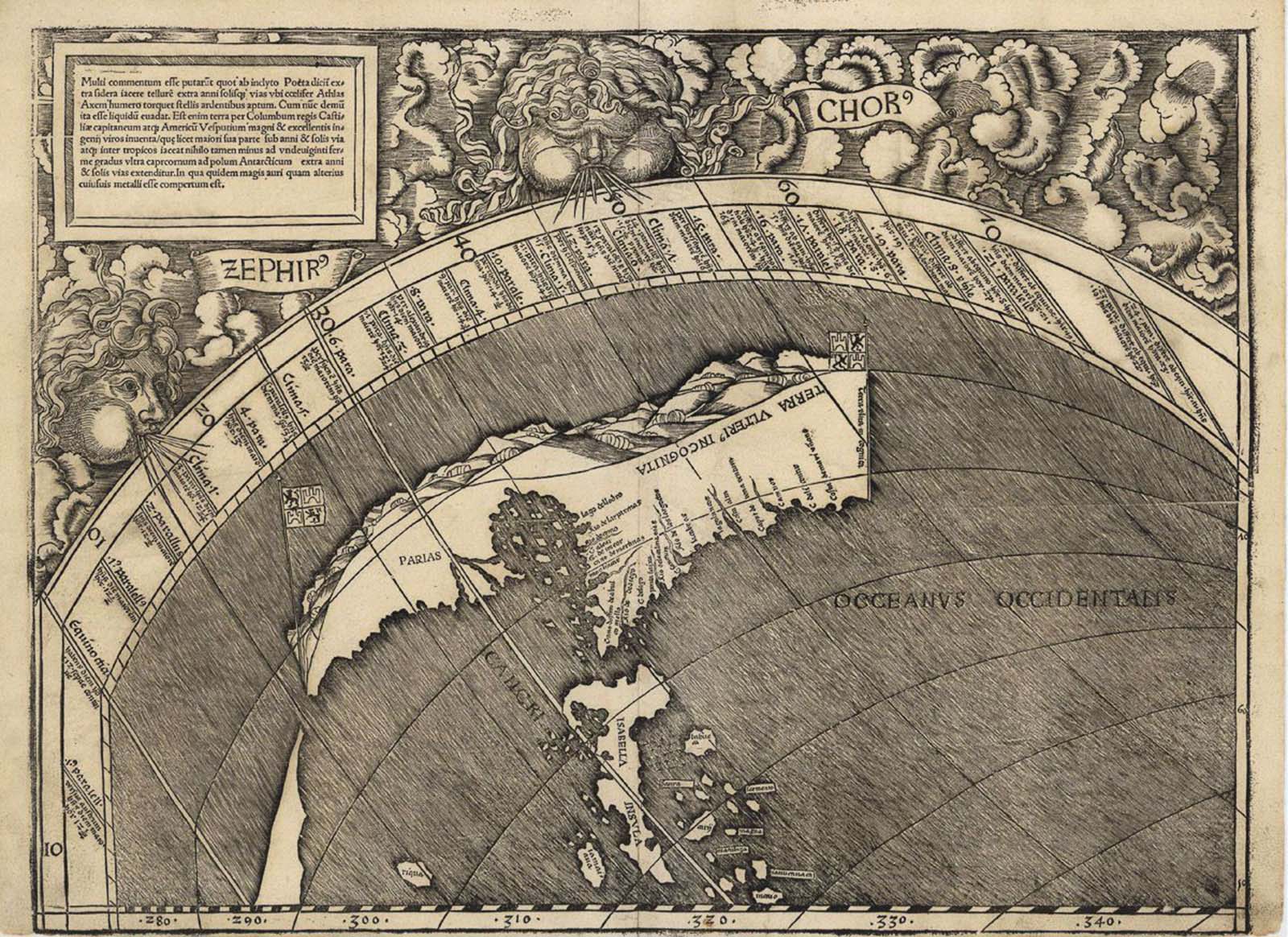

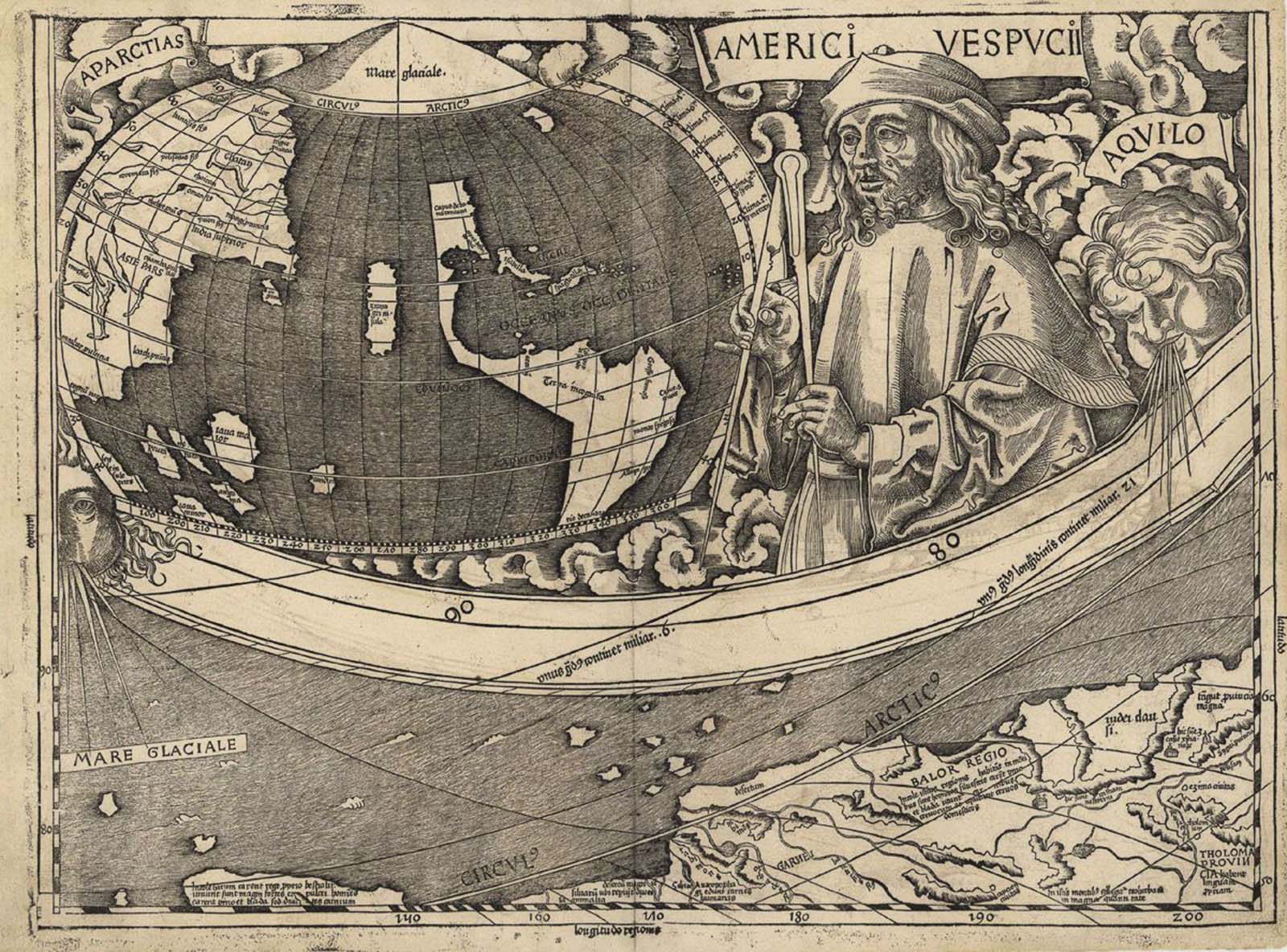

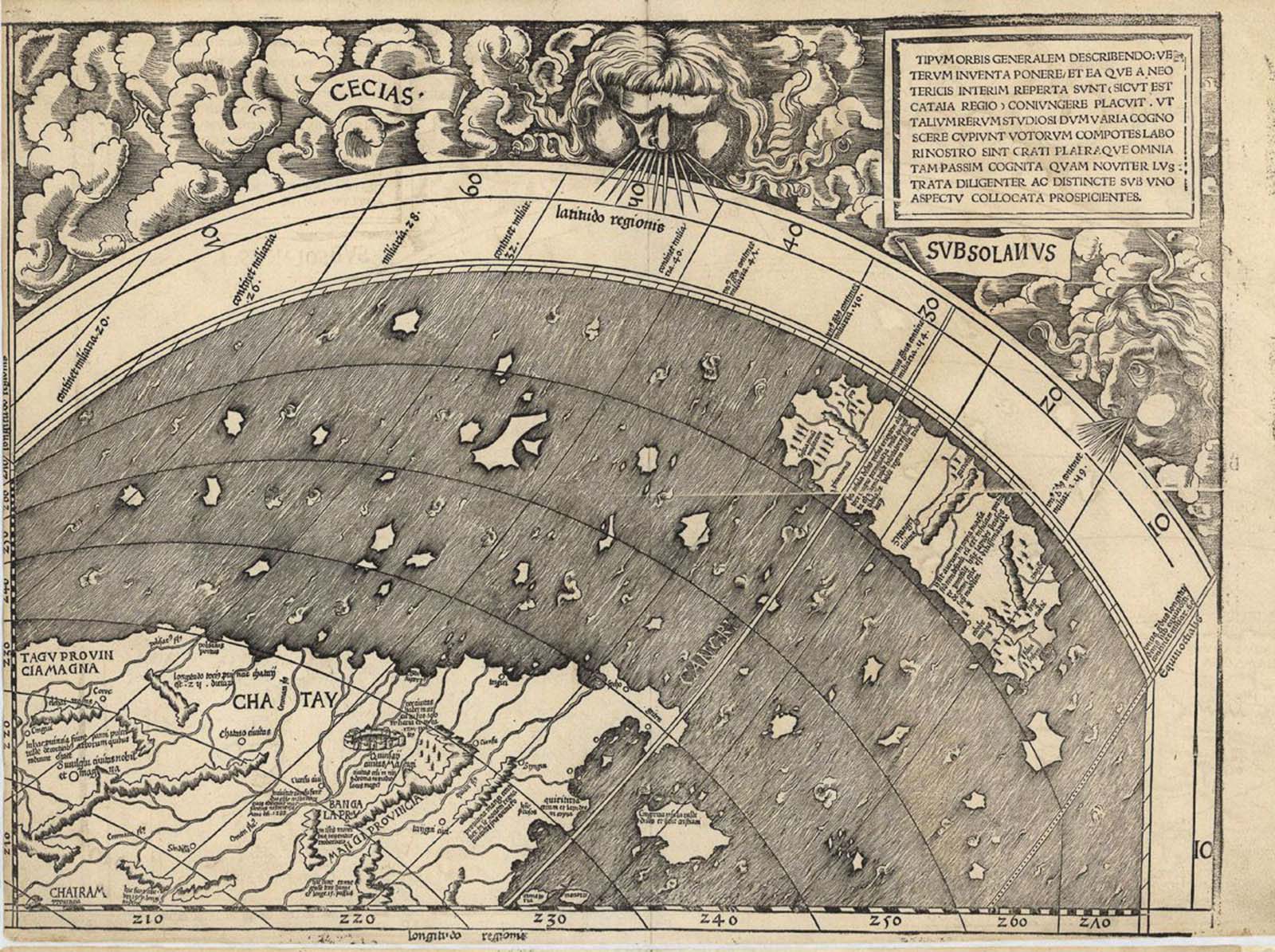

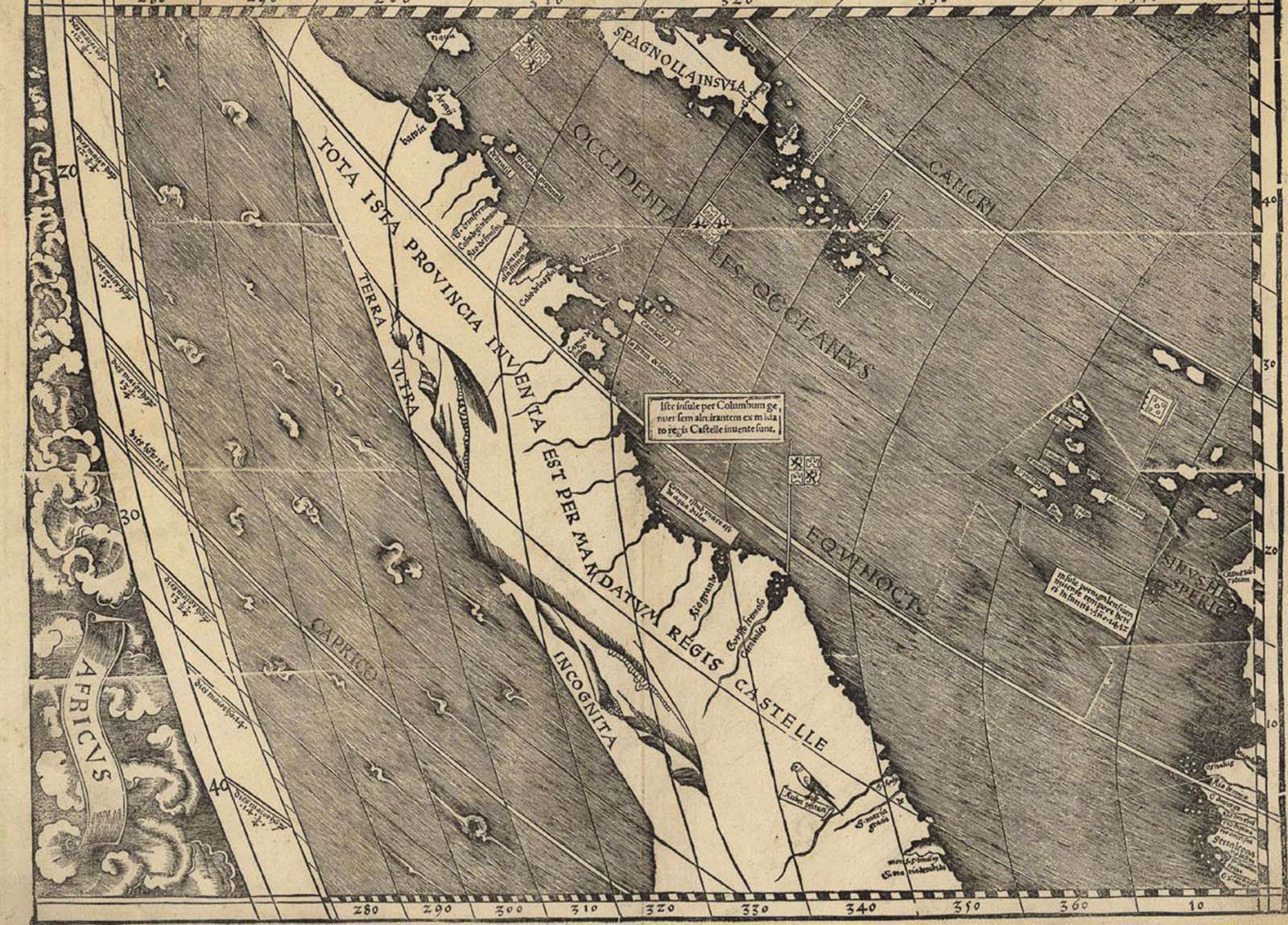

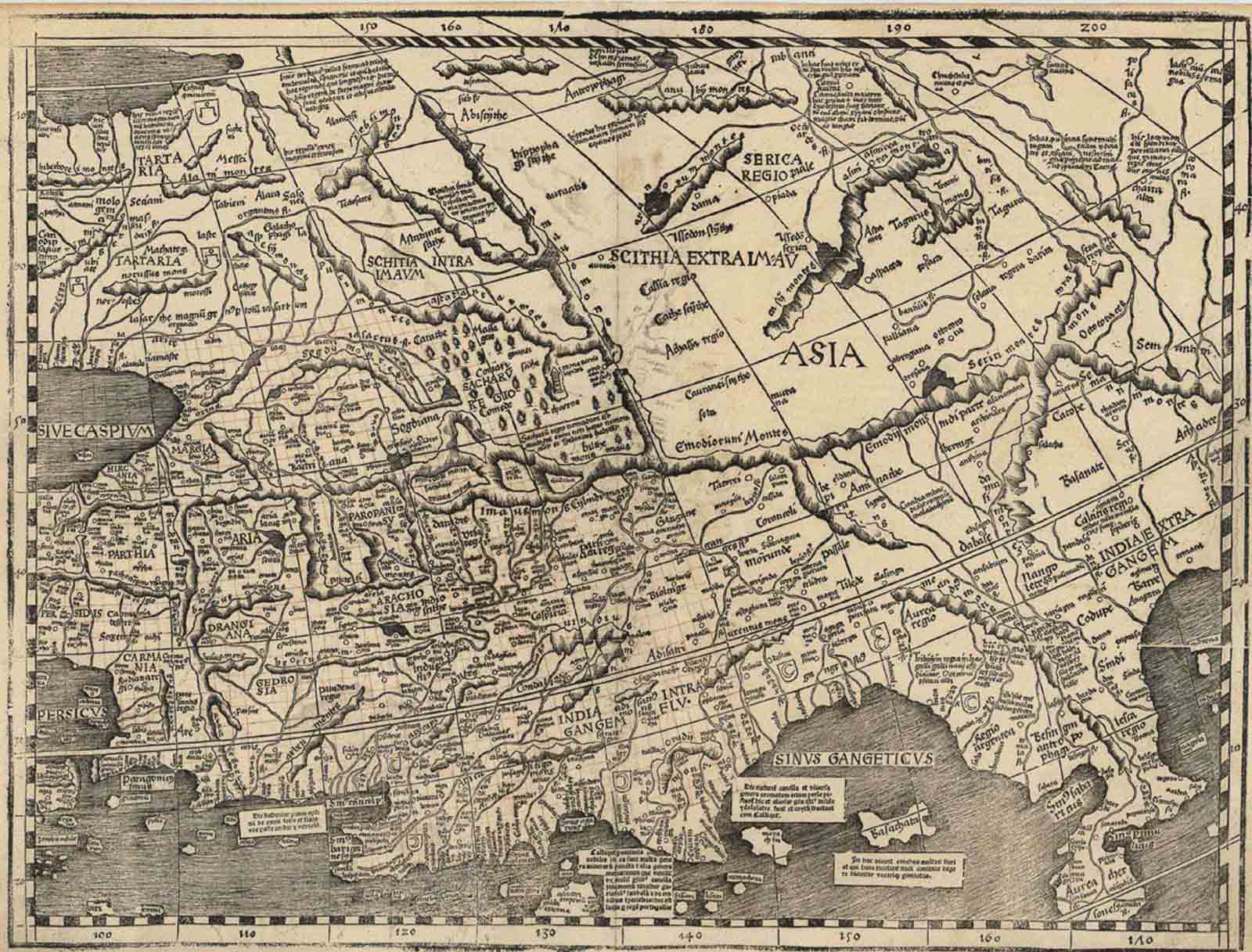

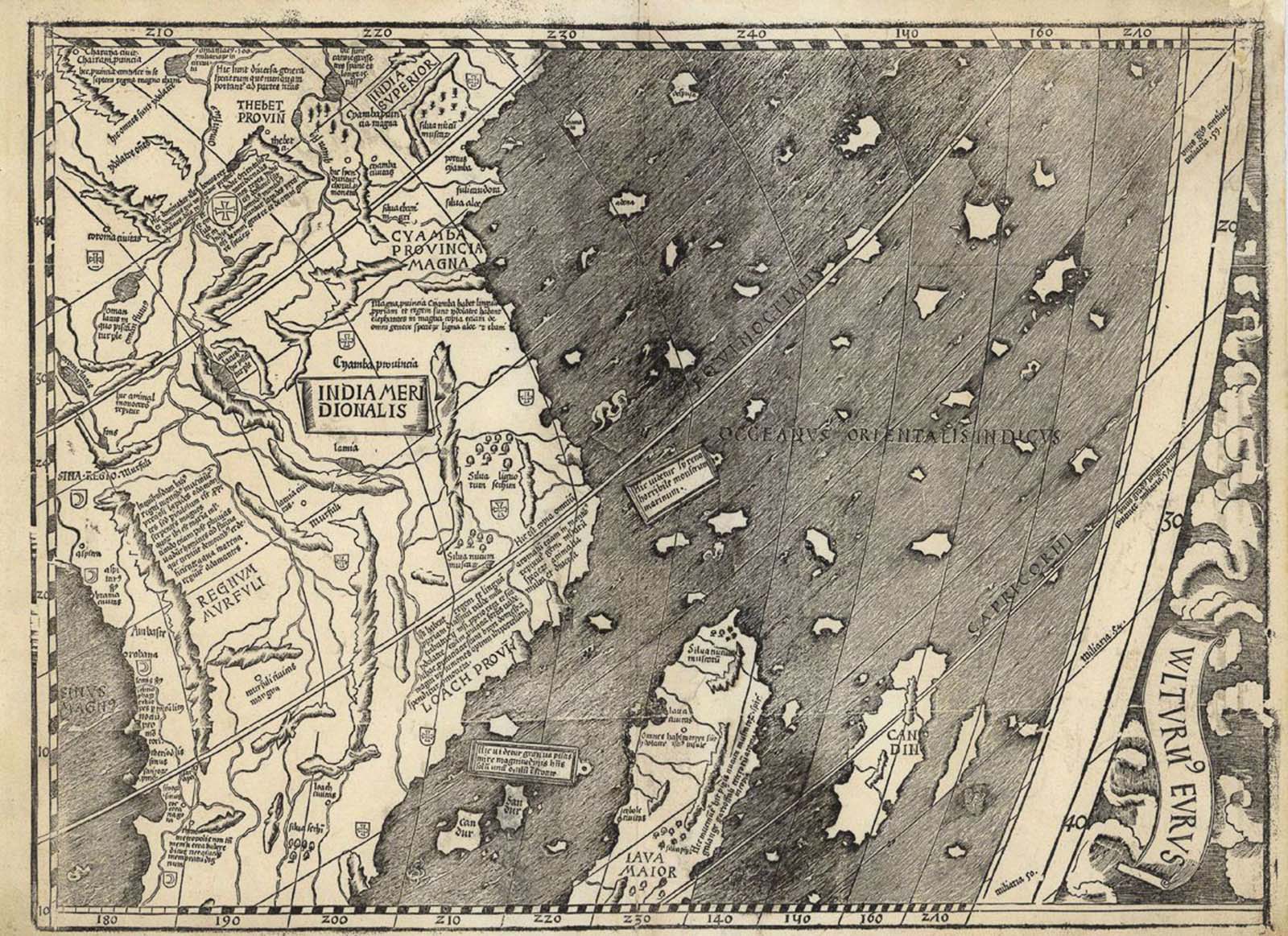

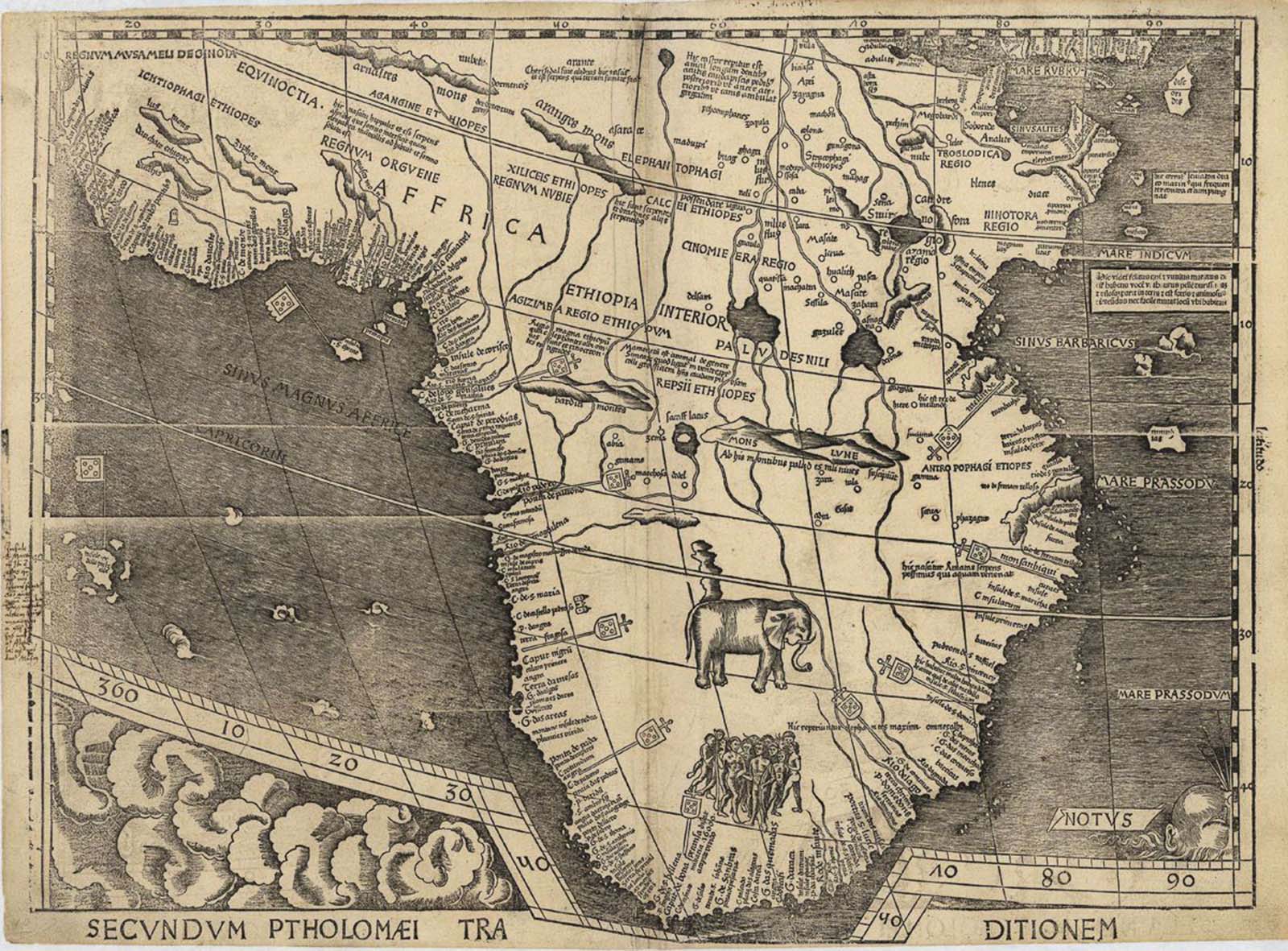

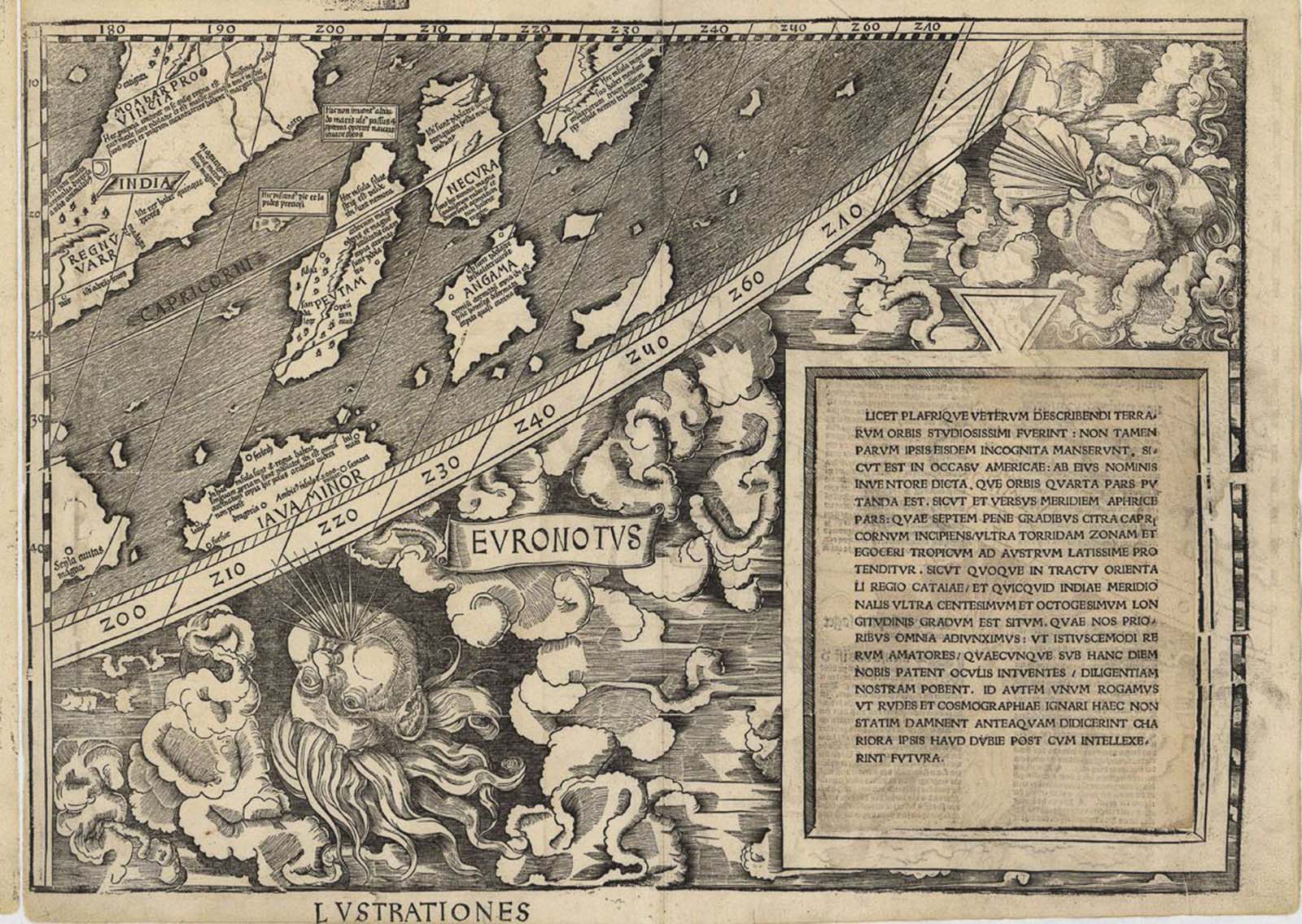

The title signaled Waldseemüller’s intention to combine or harmonize in a unified cosmographic depiction the traditional Ptolemaic geography of Europe, Asia, and Africa with the new geographical information provided by Amerigo Vespucci and his fellow discoverers of lands in the western hemisphere. He explained: “In designing the sheets of our world-map we have not followed Ptolemy in every respect, particularly as regards the new lands … We have therefore followed, on the flat map, Ptolemy, except for the new lands and some other things, but on the solid globe, which accompanies the flat map, the description of Amerigo that is appended hereto”. Waldseemüller christened the new lands “America” in recognition of Vespucci’s understanding that a new continent had been uncovered as a result of the voyages of Columbus and other explorers in the late fifteenth century. This is the only known surviving copy of the first printed edition of the map, which, it is believed, consisted of 1,000 copies. The map supported Vespucci’s revolutionary concept by portraying the New World as a separate continent, which until then was unknown to the Europeans. It was the first printed map to depict clearly a separate Western Hemisphere, with the Pacific as a separate ocean. The map forever changed the European understanding of a world divided into only three parts—Europe, Asia, and Africa. The wall map consists of twelve sections printed from woodcuts measuring 18 by 24.5 inches (46 cm × 62 cm). Each section is one of four horizontally and three vertically when assembled. The map uses a modified Ptolemaic map projection with curved meridians to depict the entire surface of the Earth. On the map, the unexplored continent of North America is called “Parias,” while the newly christened America describes the South American coast all the way down to the present-day port of Cananéia, just south of São Paulo, Brazil. In the east, the map extends to a region labeled “India Meridionalis” or “Southern India” — the great peninsula of Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam — and to scattered and unlabeled islands beyond. While some maps after 1500 show, with ambiguity, an eastern coastline for Asia distinct from the Americas, the Waldseemüller map apparently indicates the existence of a new ocean between the trans-Atlantic regions of the Spanish discoveries and the Asia of Ptolemy and Marco Polo as exhibited on the 1492 Behaim globe. The first historical records of Europeans to set eyes on this ocean, the Pacific, are recorded as Vasco Núñez de Balboa in 1513. That is five to six years after Waldseemüller made his map. In addition, the map apparently predicts the width of South America at certain latitudes to within 70 miles. Historians have theorized that Waldseemüller incorporated the ocean into his map because Vespucci’s accounts of the Americas, with their so-called “savage” peoples, could not be reconciled with contemporary knowledge of India, China, and the islands of the Indies. Thus, in the view of Whitfield, Waldseemüller reasoned that the newly discovered lands could not be part of Asia, but must be separate from it, a leap of intuition that was later proved uncannily precise. (Photo credit: Library of Congress). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe