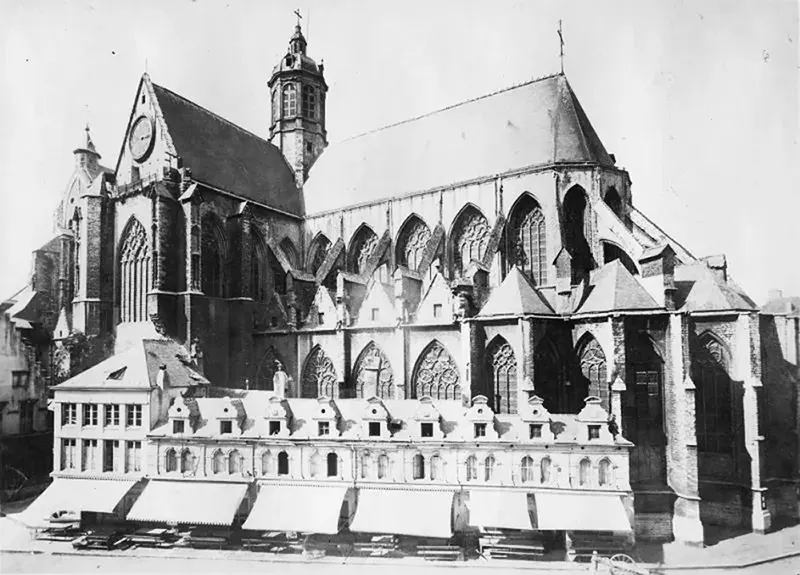

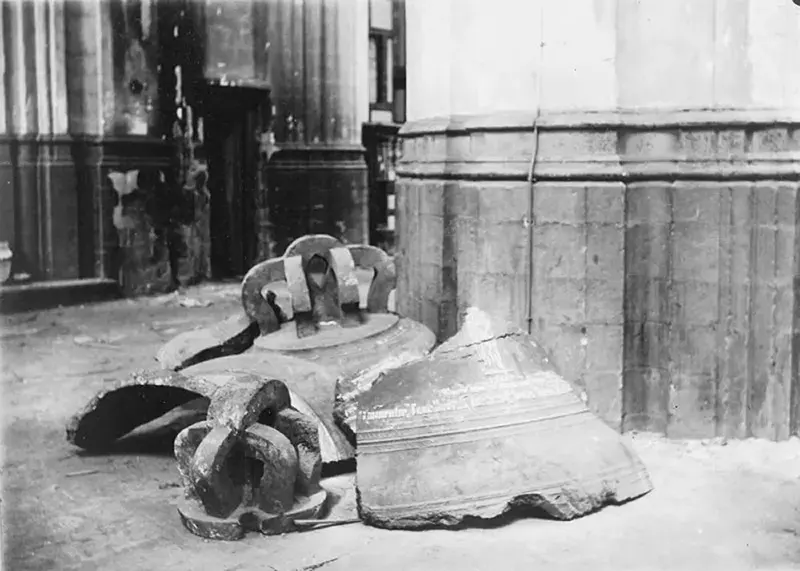

The German First Army had occupied Louvain without a fight on 19 August 1914 as part of the opening move og what would later become known as the First World War. Sometime around 8 PM on 25 August, however, sporadic rifle fire broke out on the city streets. What provoked the initial shots is still unknown. Subsequent German claims that Belgian franc-tireurs, or irregular militiamen, had opened fire on their soldiers are highly improbable, as no claims of organized guerrilla activity anywhere in 1914 Belgium have been successfully substantiated. Indeed, the Belgian government was at pains to warn the citizens of Louvain (Leuven) not to provoke German reprisals by acts of resistance. It is more likely that retreating elements of the German First Army, temporarily pushed back into town by counterattack by the Belgian 6th Division on the evening of the 25th, were misidentified by nervous sentries, provoking a confused and escalating exchange of “friendly fire.” In the following events, the Germans realized there was no serious attack and took revenge on the people of Leuven. Civilians were shot or bayoneted, homes were set on fire, and some bodies showed signs of torture. Many of those killed were randomly dumped in ditches and construction trenches. The mayor of the city and the rector of the university were summarily executed. At around 11:30 p.m., German soldiers broke into the university’s library (located in the 14th-century cloth hall), which held significant special collections, including medieval manuscripts and books, and set it on fire. Within ten hours, the library and its collection were completely destroyed. The fire continued to burn for several days. The rector of the American College of Louvain was rescued by the Brand Whitlock, the U.S. ambassador, who recorded the rector’s account of “the murder, the lust, the loot, the fires, the pillage, the evacuation and the destruction of the city” as well as the deliberate incineration of the library’s incunabula. The burning of the University of Louvain’s library caused the destruction of more than 230,000 books, including 750 medieval manuscripts. Personal libraries and the papers of notaries, solicitors, judges, professors, and physicians were also destroyed. The killings and other acts of brutality took place throughout the next night and day. The day after that, the German army bombarded the town with five shells. The town was thoroughly pillaged, with many German officers and men engaging in mass plunder of money, wine, silver, and other objects of value and killing those who resisted or did not understand. In the town, some 1,100 buildings were destroyed, variously estimated to constitute one-sixth or more than one-fifth of the town’s structures. The town hall was saved because it was the site of the German headquarters. Some 248 civilians were killed, and most of the city’s 42,000 residents were exiled by force into the countryside, with some being taken from their homes at gunpoint. Approximately 1,500 citizens of the town, including women, children, and four of the hostages, were deported to Germany in railway cattle wagons. The German atrocities and the cultural destruction caused worldwide outrage. It greatly harmed Germany’s standing in the neutral countries. In Britain, Prime Minister H. H. Asquith wrote that “the burning of Louvain is the worst thing [the Germans] have yet done. It reminds one of the Thirty Years’ War … and the achievements of Tilly and Wallenstein.” Irish nationalists, led by John Redmond, condemned the German atrocities Intellectuals and journalists in Italy condemned the German act, and it contributed to Italy distancing itself from Germany and Austria and drifting toward the Allies. The Daily Mail called it the “Holocaust of Louvain.”

(Photo credit: Archives of Leuven / Bundesarchiv / Wikimedia Commons / World War I: A Student Encyclopedia). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe