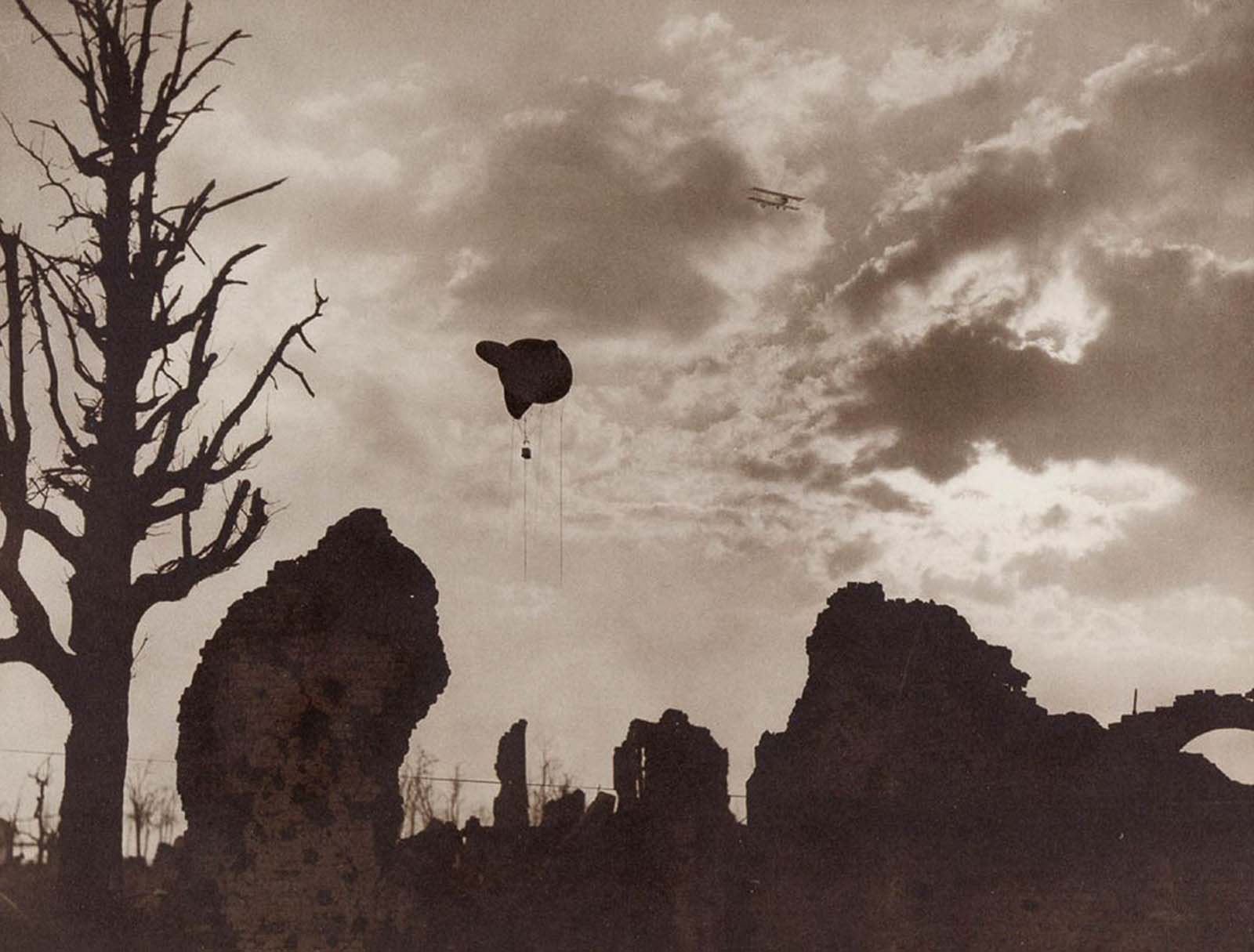

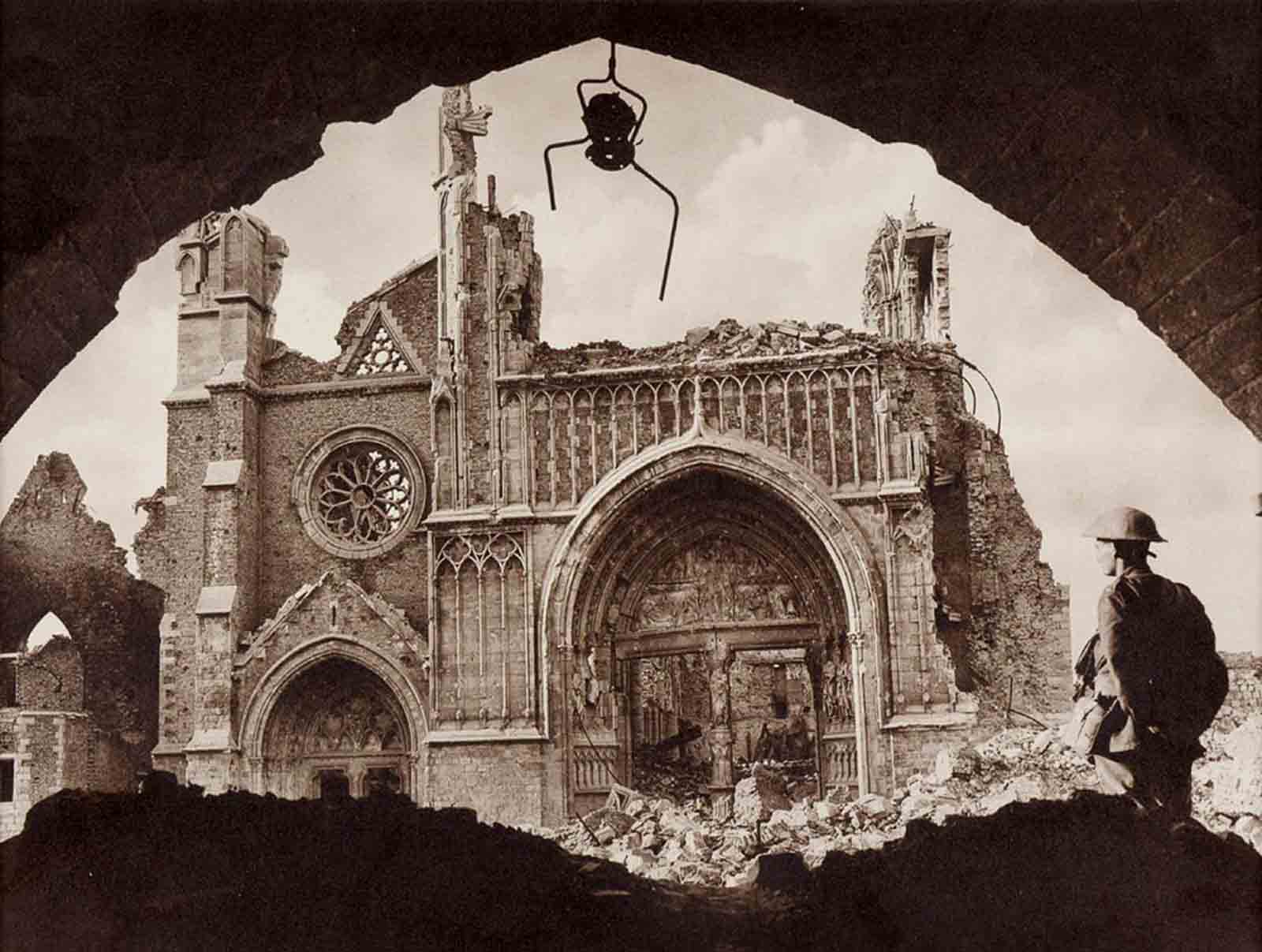

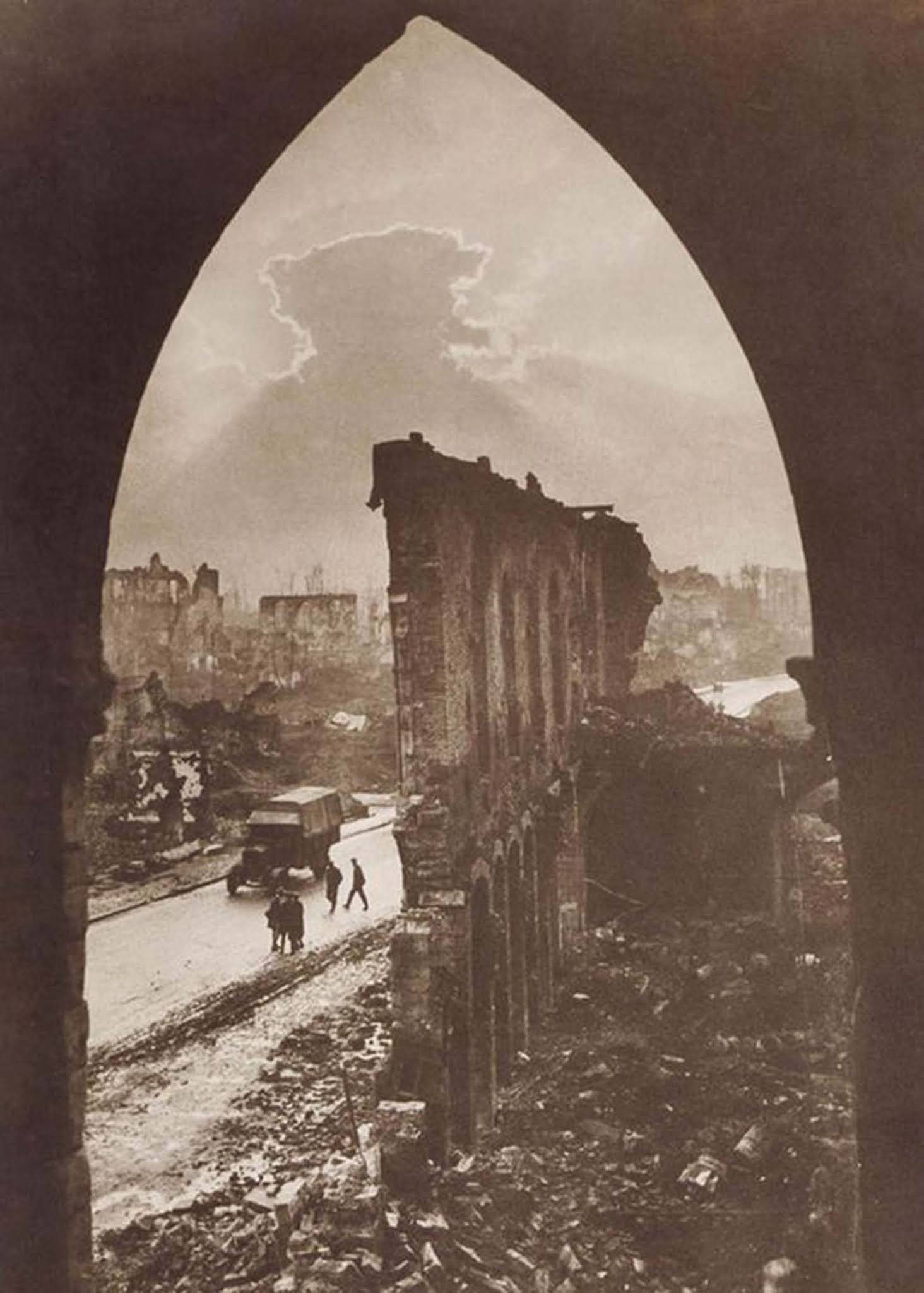

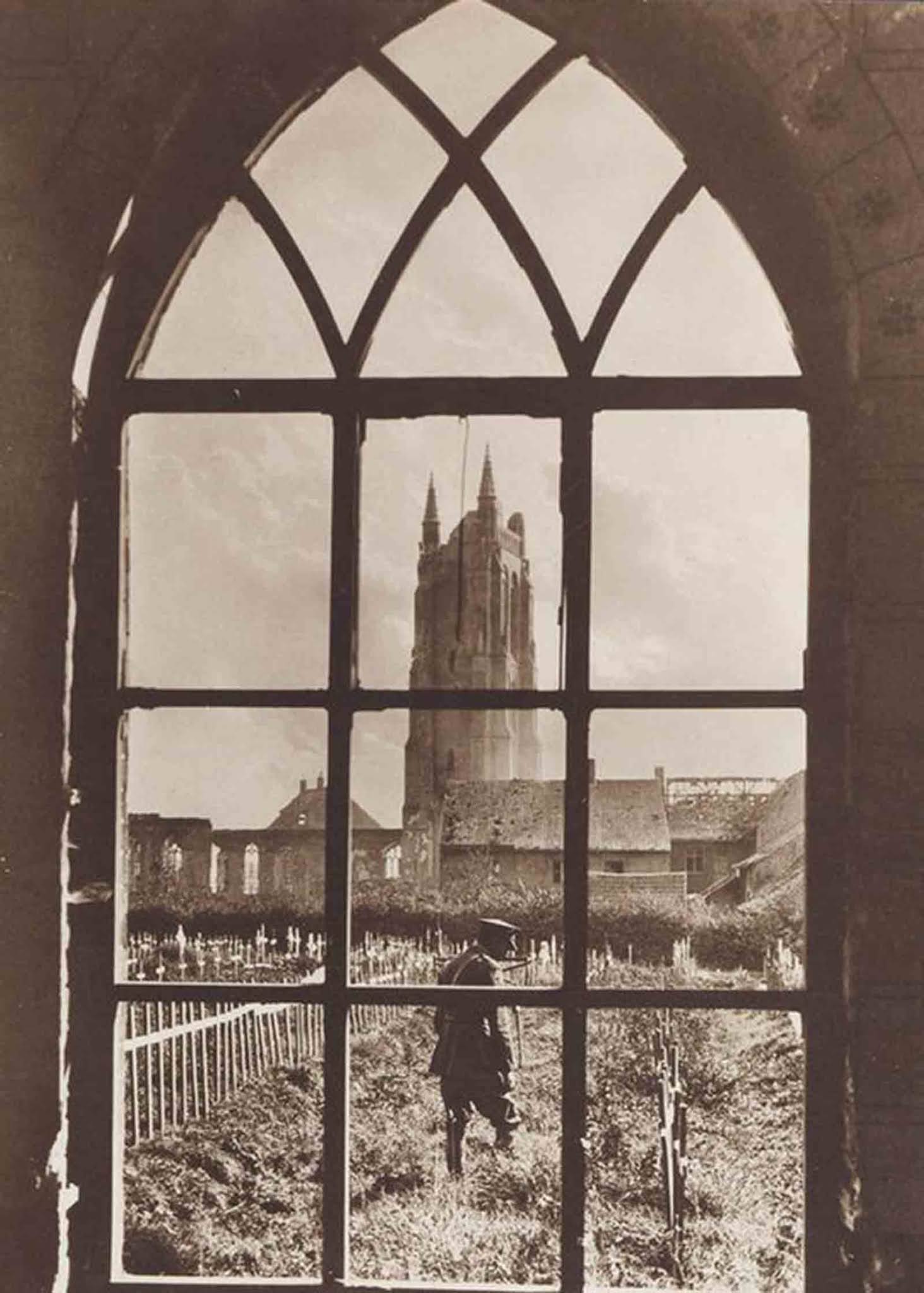

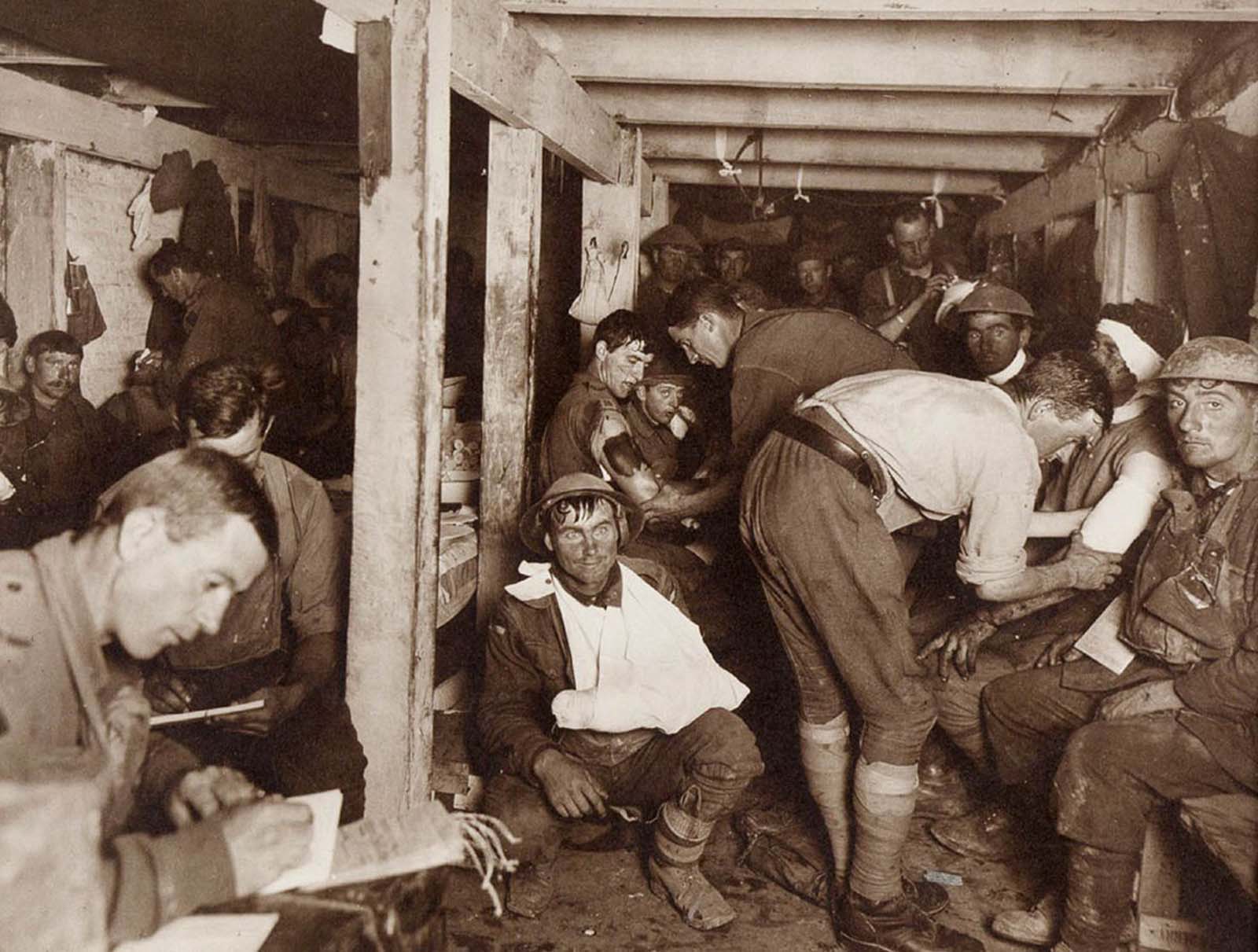

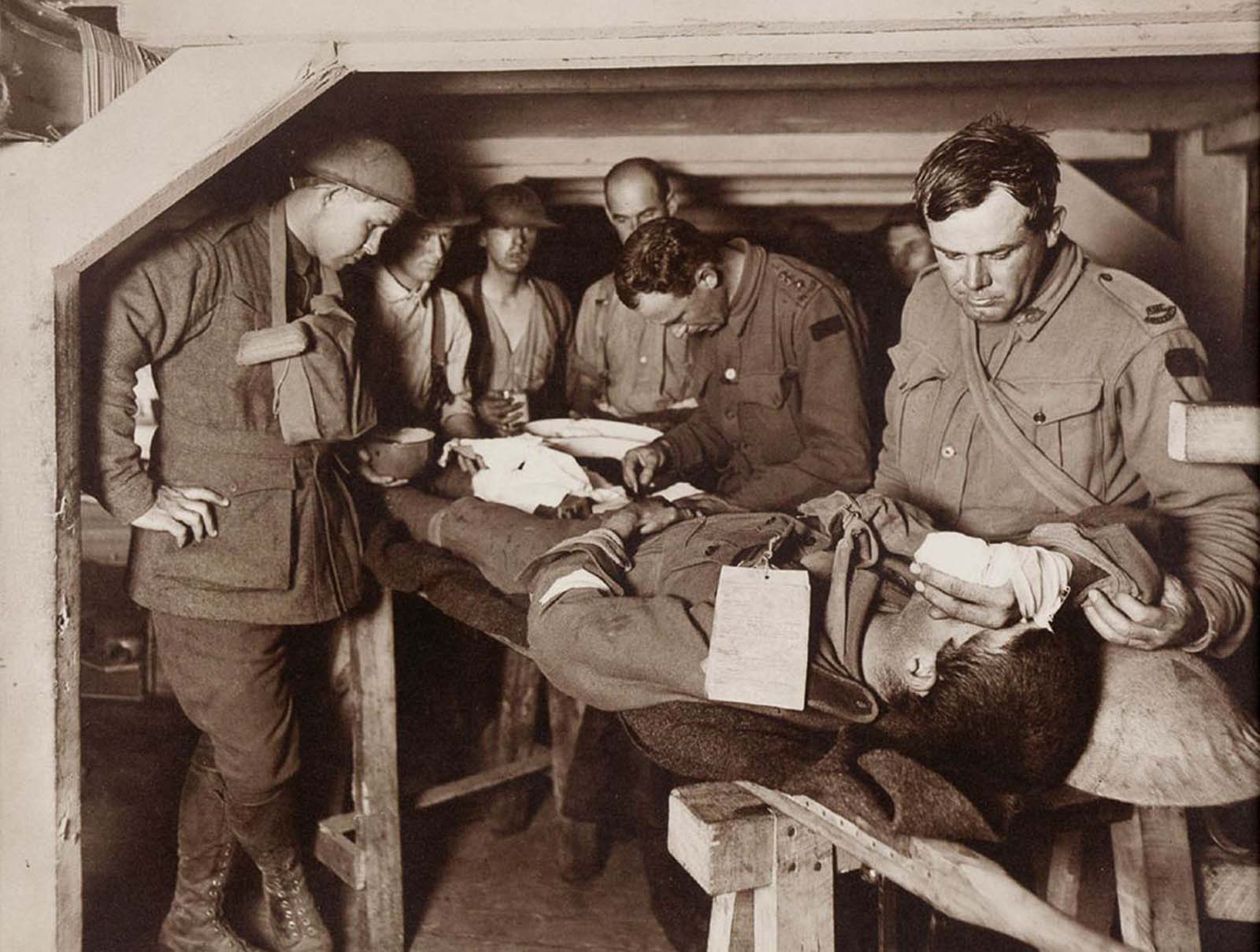

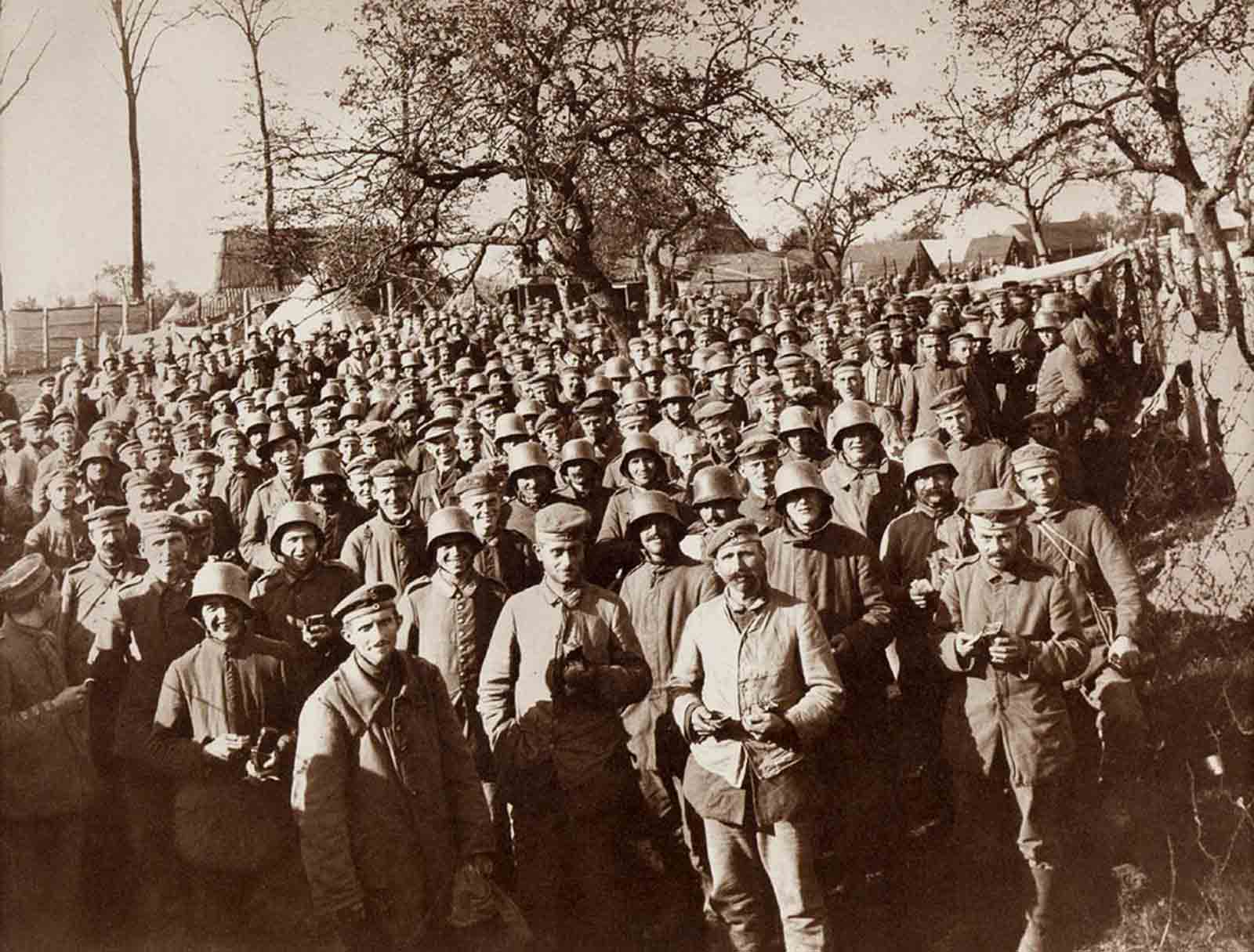

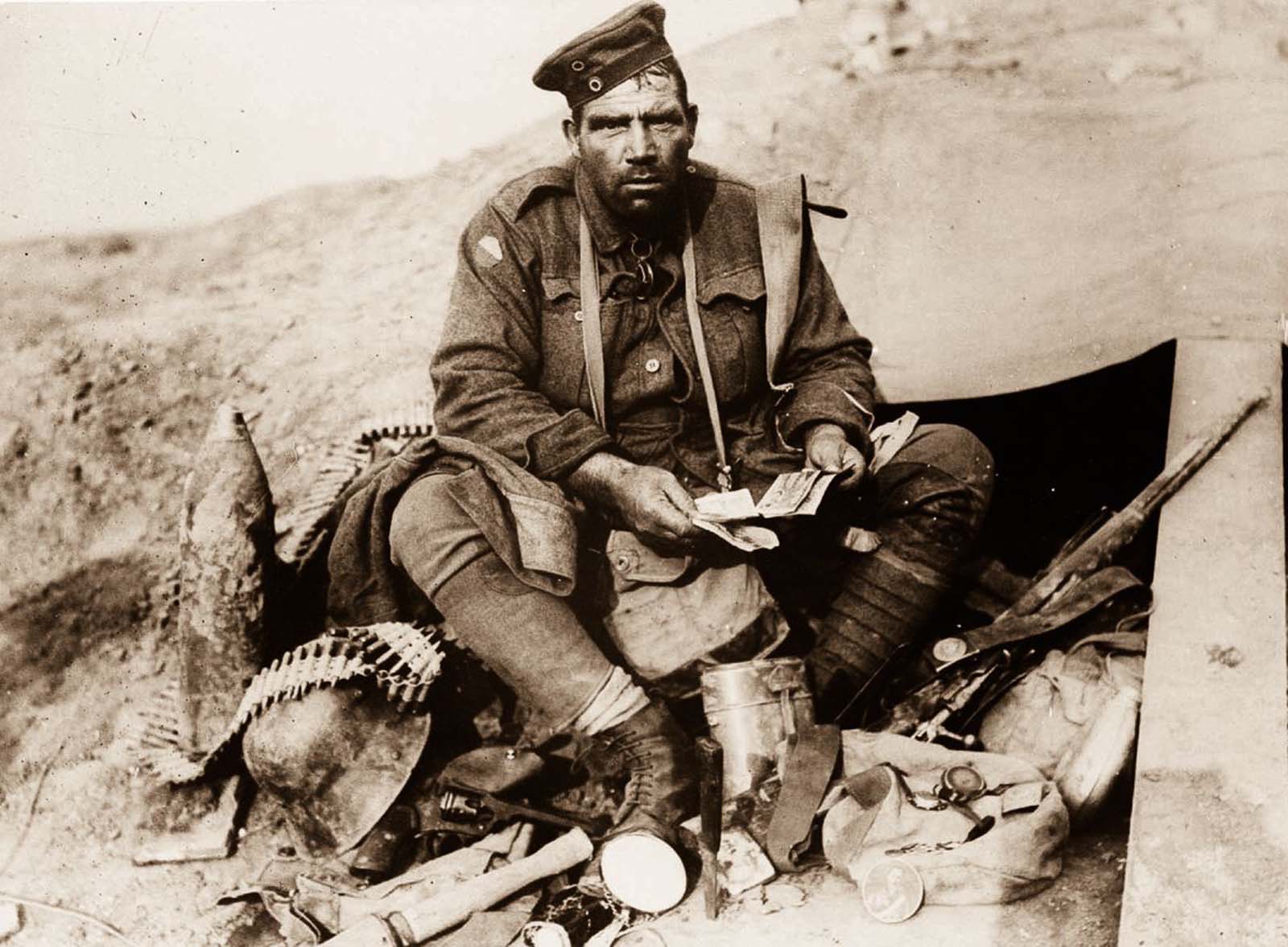

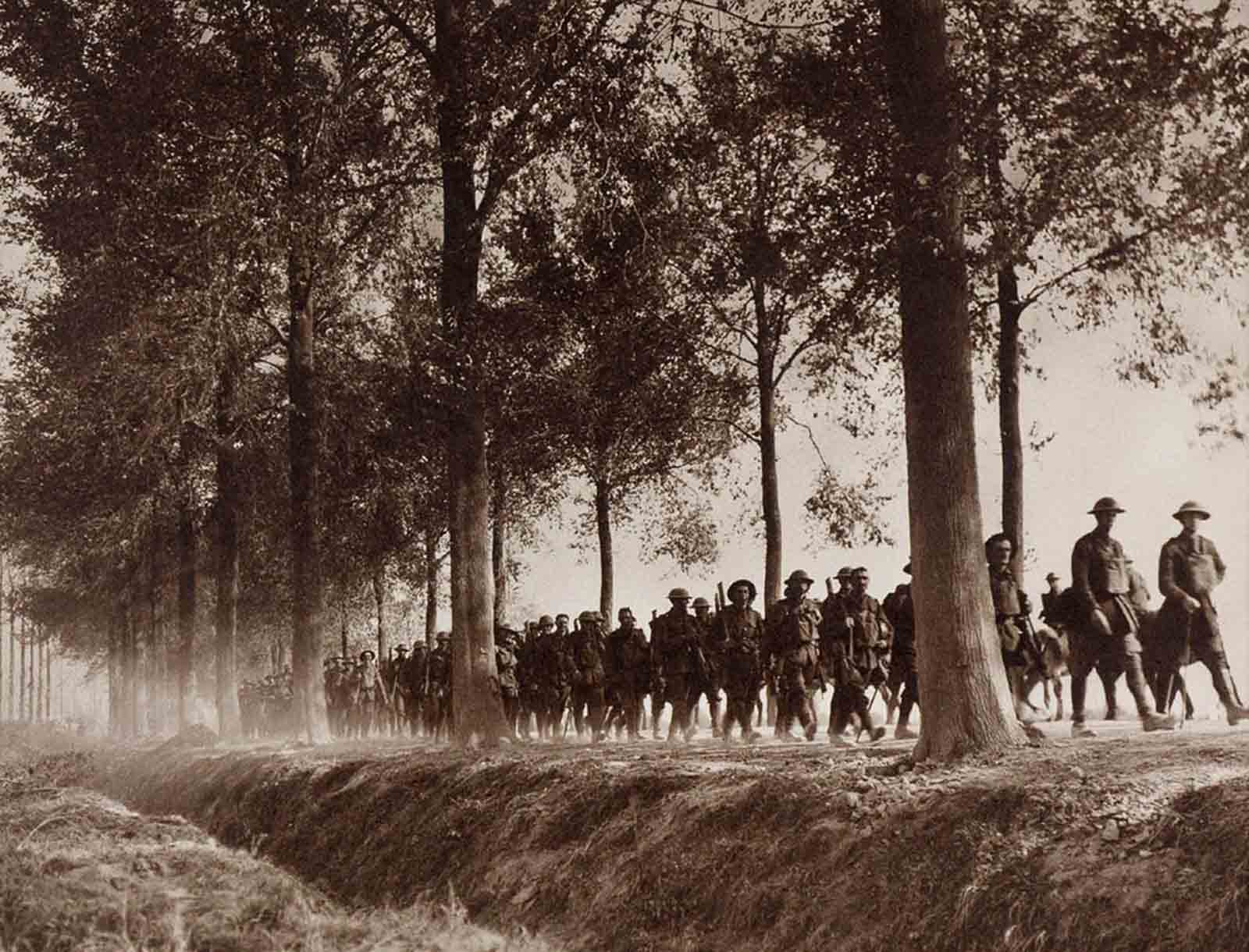

When he arrived at the Western Front his rank was honorary captain, but the troops, seeing how he took risks to get his pictures, dubbed him “the mad photographer”. His job was to document the war effort, to provide images to the media, and to capture the heroism of the Australians to show those back home. What he captured, however, was hell on earth. He shot photographs of battles and their haunting aftermath and was horrified by the scenes of blood, death, and devastation that were so common on the Western Front. This photo collection from the Third Battle of Ypres (1917), part of State Library of New South Wale, is accompanied by a few excerpts from Hurley’s diary, in which he describes his war experiences in detail, including the horrors he witnesses, the devastation, the pity he feels for the German soldiers, his disgust with the war and frustration over his photo techniques. In keeping with his adventurous spirit, Hurley took considerable risks to photograph his subjects, also producing many rare panoramic and color photographs of the conflict. His famous black-and-white photographs of lonely soldiers and desolate landscapes are shocking and moving, but some have also been called “fake”, even though he was there. Hurley would have soldiers restage actions and events that he had missed, and, most controversially, he created composite tableaux, often drawing on several photographic negatives to heighten the drama. It was a trick as old as photography itself, yet many of his colleagues were against it. During this time, Hurley clashed with the official historian, Captain Charles Bean, about truth and photography. They had both been appointed by the Australian War Records Section of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) to document the war for posterity. Hurley, having assessed his task over a number of weeks, argued that it was impossible to capture the essence of what he saw in a single negative. He wrote: “None but those who have endeavored can realize the insurmountable difficulties of portraying a modern battle by the camera. To include the event in a single negative, I have tried and tried, but the results are hopeless… Now, if negatives are taken of all the separate incidents in the action and combined, some idea may then be gained of what a modern battle looks like.” Bean, however, was not convinced and referred to the images as ‘fakes’. He believed that photographs were ‘sacred records’ and should allow future generations to see the plain, simple truth. Hurley stood his ground but eventually resigned when he was ordered not to produce composite images. In total, he photographed the Western Front for three months before moving to the Middle East where he photographed the activities of the Australian Mounted Division. Between 1915 and 1917 there were several offensives along the Western Front. The attacks employed massive artillery bombardments and massed infantry advances. Entrenchments, machine gun emplacements, barbed wire and artillery repeatedly inflicted severe casualties during attacks and counter-attacks and no significant advances were made. Among the most costly of these offensives were the Battle of Verdun, in 1916, with a combined 700,000 casualties, the Battle of the Somme, also in 1916, with more than a million casualties, and the Battle of Passchendaele, in 1917, with 487,000 casualties. By 1917, the size of the British Army on the Western Front had grown to two-thirds the total numbers in the French forces. In April 1917 the BEF began the Battle of Arras. The Canadian Corps and the 5th Division attacked German lines at Vimy Ridge, capturing the heights and the First Army to the south achieved the deepest advance since trench warfare began. Later attacks were confronted by German reinforcements defending the area using the lessons learned on the Somme in 1916. British attacks were contained and, according to Gary Sheffield, a greater rate of daily loss was inflicted on the British than in “any other major battle.” During the winter of 1916–1917, German air tactics had been improved, a fighter training school was opened at Valenciennes and better aircraft with twin guns were introduced. The result was near disastrous losses for Allied air power, particularly for the British, Portuguese, Belgians and Australians who were struggling with outmoded aircraft, poor training and weak tactics. From Frank Hurley’s diary. Sept. 17, 1917. The tunnelers are excavating a series of underground dugouts, which will be occupied by the headquarters of our infantry. It is a wretched job, as they are working 25 feet below the surface level and most of the time knee-deep in mud. From the roof trickles water and mud, which they jocularly term “Hero Juice” on account of it percolating through tiers and tiers of buried corpses. Sept. 21, 1917. It was wondrously quiet, only an occasional shell was fired — the aftermath of the storm, and it sounded for all the world like the occasional boom of a roller on a peaceful beach, with the swish of the water corresponding to the scream of the shell. Aug. 23, 1917. Hill 60 long-delayed our infantry advance, owing to its commanding position and the almost impregnable concrete emplacements and shelters constructed by the Boche. We eventually won it by tunneling underground and then exploding three enormous mines, which practically blew the whole hill away and killed all the enemy on it. It’s the most awful and appalling sight I have ever seen. The exaggerated machinations of hell are here typified. Everywhere the ground is littered with bits of guns, bayonets, shells and men. Way down in one of these mine craters was an awful sight. There lay three hideous, almost skeleton decomposed fragments of corpses of German gunners. Oh the frightfulness of it all. To think that these fragments were once sweethearts, maybe, husbands or loved sons, and this was the end. Oct. 11, 1917. One dares not venture off the duckboard or he will surely become bogged, or sink in the quicksand-like slime of rain-filled shell craters. Add to this frightful walking a harassing shellfire and soaking to the skin, and you curse the day that you were induced to put foot on this polluted damned ground. Sept. 2, 1917. Aeroplanes are far more numerous here than birds. They fly the skies at all times. In gale, rain, day and night the buzz of the engines can be heard like the buzzing of innumerable bee hives; above this buzzing one hears the occasional, crackle, crackle, crackle, of their Lewis gun, and looking up is spellbound, watching a duel between a Boche & British plane. Sept. 3, 1917. To drive the Boche from Ypres, it was necessary to practically raze the town; and now that we hold it we are shelled in return, but shelling now makes little difference, for the fine buildings and churches are scarce left stone on stone. Roaming amongst the domestic ruins made me sad. Here and there were fragments of toys: what a source of happiness they once were. The strafed trees were coming back to life and budding, and there beside a great shell crater blossomed a single rose. How out of place it seemed amidst all this ravage. I took compassion on it and plucked it — The last rose of Ypres. Oct. 1, 1917. Our Authorities here will not permit me to pose any pictures or indulge in any original means to secure them. They will not allow composite printing of any description, even though such be accurately titled nor will they permit clouds to be inserted in a picture. As this absolutely takes all possibilities of producing pictures from me, I have decided to tender my resignation at once. I conscientiously consider it but right to illustrate to the public the things our fellows do and how war is conducted. These can only be got by printing a result from a number of negatives or reenactment. Oct. 2, 1917. I sent in my resignation this morning and await the result of igniting the fuse. It is disheartening, after striving to secure the impossible and running all hazards to meet with little encouragement. Oct. 6, 1917. I am sending in 150 negatives this week. Headquarters have given me permission to make six combination enlargements in the exhibition! So I withdrew my resignation. They must at least appreciate my efforts, as they were dead against this being done. However, it will be no delusion on the public as they will be distinctly titled, setting forth the number of negatives used, etc. (Photo credit: Frank Hurley / State Library of New South Wales / The Australian / Wild Reflections Photography). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe