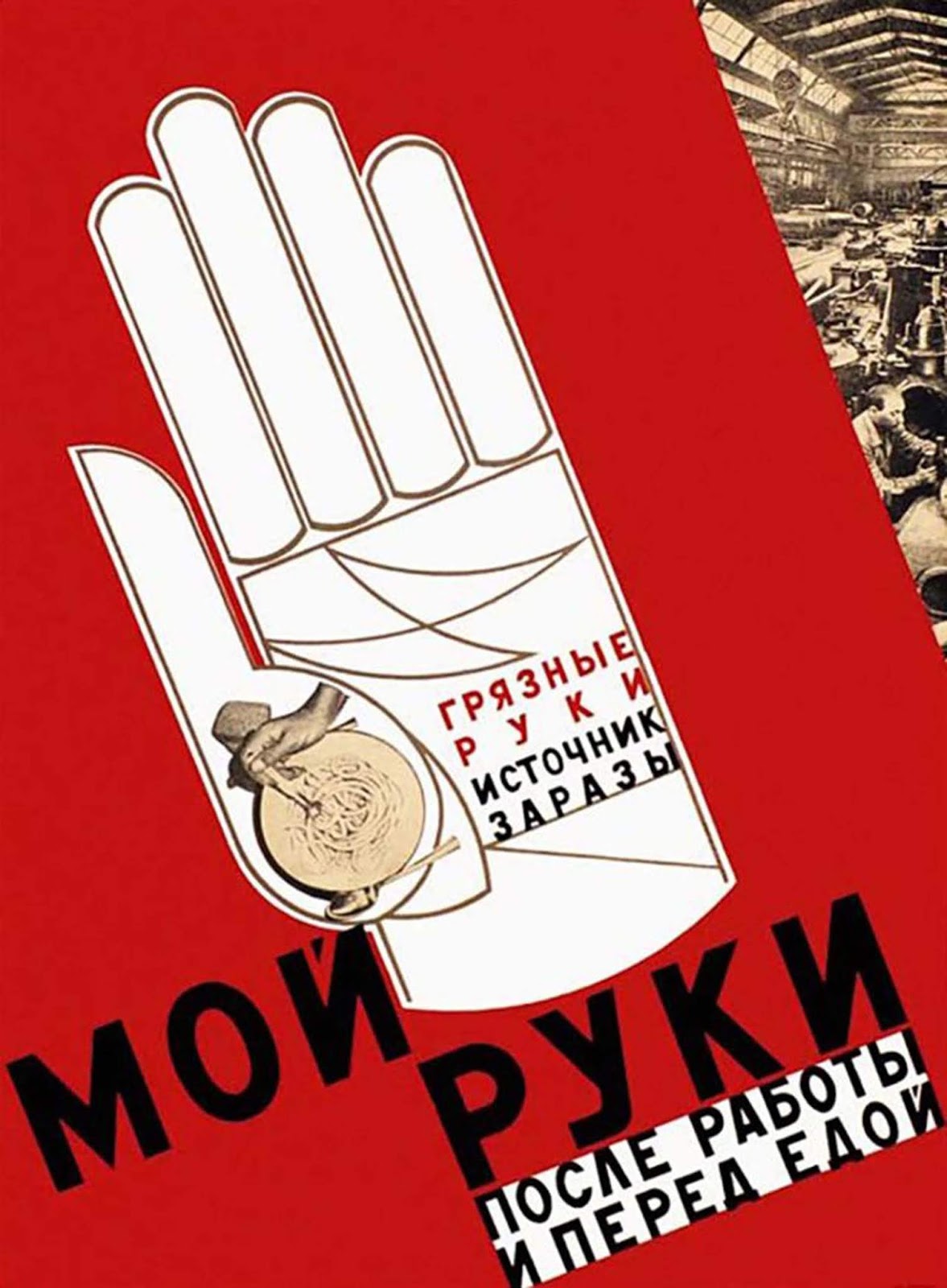

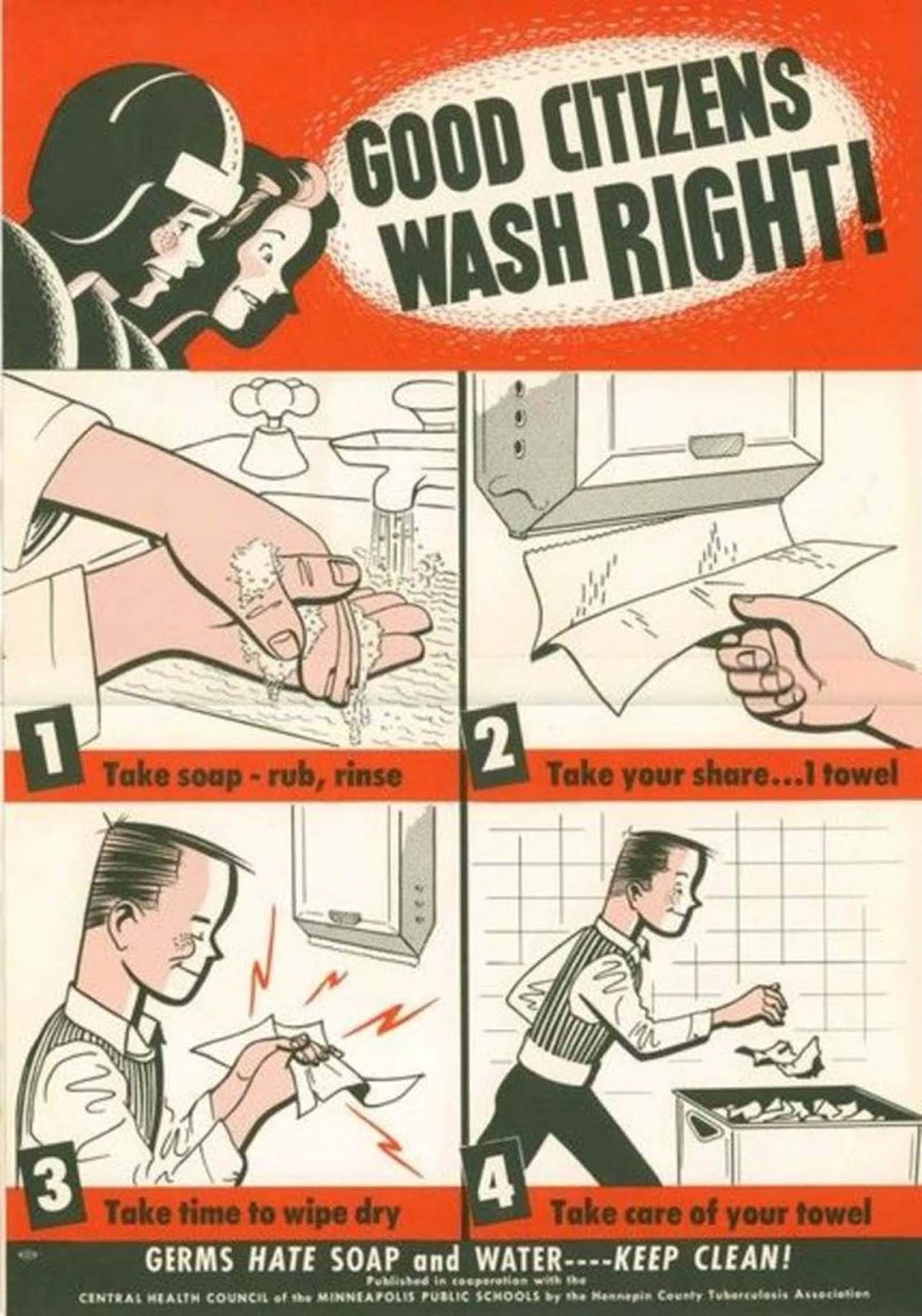

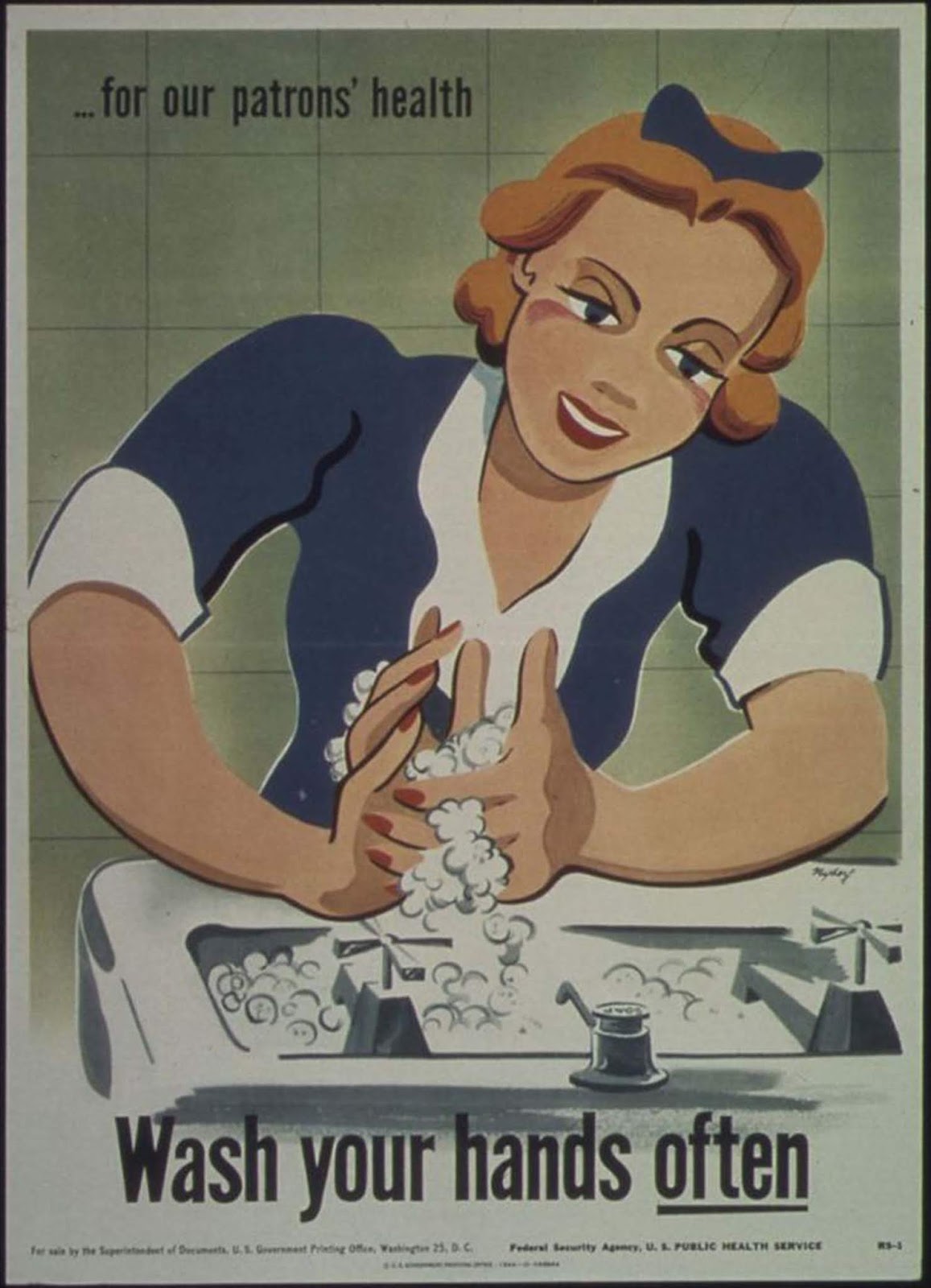

The conclusion followed his frustration at being unable to find a cause for the deaths of women in bed after childbirth. Although most women delivered at home, those who had to seek hospitalization because of poverty, illegitimacy, or obstetrical complications faced mortality rates ranging as high as 25–30 percent. Some thought that the infection was induced by overcrowding, poor ventilation, the onset of lactation, or miasma. Semmelweis proceeded to investigate its cause over the strong objections of his chief, who, like other continental physicians, had reconciled himself to the idea that the disease was unpreventable. When one of Semmelweis’ colleagues also died of “childbed fever,” it was clear the illness was not specific to the women who had given birth, but could be passed from one person to another. Semmelweis immediately introduced enforced hand-washing. He ordered the students to wash their hands in a solution of chlorinated lime before each examination. Under these procedures, the mortality rates dropped from 18.27 to 1.27 percent. The younger medical men in Vienna recognized the significance of Semmelweis’ discovery and gave him all possible assistance. Semmelweis’s observations conflicted with the established scientific and medical opinions of the time and his ideas were rejected by the medical community. Semmelweis could offer no acceptable scientific explanation for his findings, and some doctors were offended at the suggestion that they should wash their hands and mocked him for it. In 1865, the increasingly outspoken Semmelweis supposedly suffered a nervous breakdown and was treacherously committed to an asylum by his colleague. He died a mere 14 days later, at the age of 47. To remind us of the importance of hand-washing, here are a few interesting posters dating from across the 20th century. The Centers for Disease Control describes hand-washing as “do-it-yourself vaccination.” (Photo credit: National Archives). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe