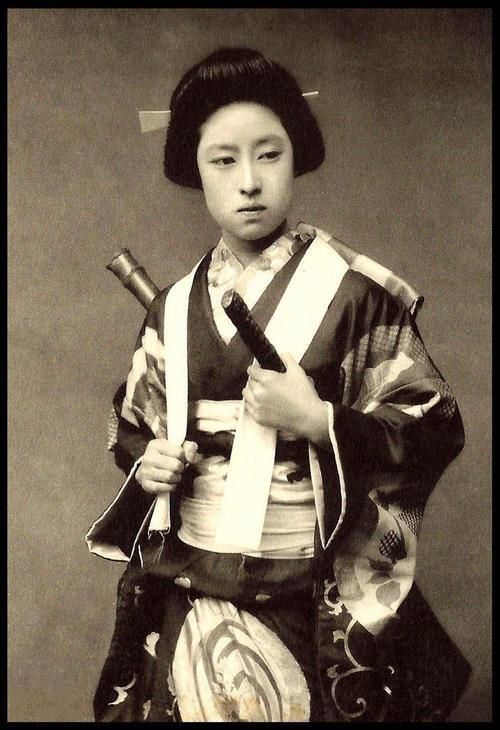

They were members of the bushi (warrior) class in feudal Japan and were trained in the use of weapons to protect their household, family, and honor in times of war. They also have an important presence in Japanese literature, with Tomoe Gozen and Hangaku Gozen as famous and influential examples representing onna-musha. Women warriors were not a rarity in feudal japan. The onna-musha lived within a warring culture and with traditions of acquiring indispensable skills in martial arts, archery, and horse riding. “Sengoku battles often took the form of sieges wherein the entire family would fight to defend the castle” so it was necessary to be able to defend your family, children, and yourself. The painting titled Boki ekotoba, dated to 1351, depicted a woman in armor, armed with naginata and bow. A journal record of “predominately female cavalry” is noted by Chancellor Toin Kinkata, who stated they, “originated in western Japan…which suggests that women from the west were most likely to serve in battle,” away from the capital cities. During the Sengoku period there are several accounts of women fighting actively on the battlefield, such as the cases of Myōrin, who inspired the people to fight against 3,000 Shimazu soldiers. Another account is that of Kaihime, who fought against the Toyotomi clan in the siege of Oshi (1590), Onamihime, who became the representative leader of the Nikaidō clan and fought in various battles against her nephew Date Masamune, and Akai Teruko, who became famous for fighting until she was 76 years old and became known as “The Strongest Woman in the Warring States Period”. The actions of Ōhōri Tsuruhime earned her the title of “Joan of Arc of Japan”, and established her as one of the most recognizable female warriors in Japanese history. Japanese women were educated solely to become wives and mothers. Although most women knew about politics, martial arts, and diplomacy, they were not allowed to succeed clan leadership. However, there were exceptions. Ii Naotora took over the clan leadership after the death of all men of the Ii family; her efforts as a leader made her clan independent, and she became a daimyō. There were many noblewomen with great political influence in their clans, even to the extent they became de facto leaders. An acceptable example of women who became known as “onna daimyō” (female lords) are Jukei-ni and Toshoin. Both women acted for a long period as rulers of their respective domains, even though they were not considered heirs. In the 16th century, there were combat units consisting only of women, as was the case of Ikeda Sen, who led 200 women musketeers (Teppo unit) in the Battle of Shizugatake and Battle of Komaki-Nagakute. Otazu no kata fought alongside 18 armed maids against Tokugawa Ieyasu’s troops. Ueno Tsuruhime led thirty-four women in a suicidal charge against the Mōri army. Tachibana Ginchiyo, leader of the Tachibana clan, fought with her female troops in the Kyushu Campaign (1586), and in the siege of Yanagawa (1600) she organized a resistance formed by nuns against the advance of the Eastern Army. In 1580, a woman from the Bessho clan joined a rebellion against Toyotomi Hideyoshi during the siege of Miki. Her husband Bessho Yoshichika was one of the leaders of the rebellion, and she played a key role during the siege, allying herself with the Mori clan. The rebellion lasted three years, until Bessho Nagaharu surrendered the castle to Hideyoshi. Lady Bessho committed suicide shortly after. In 1582, Oda Nobunaga launched a final attack on the Takeda clan in a series of battles known as the Battle of Tenmokuzan. Oda Nobutada (son of Nobunaga) led 50,000 soldiers against 3,000 Takeda allies during the siege of Takato castle. During this battle, it is recorded in the compilation of chronicles from the Oda clan, Shinchō kōki, that a woman from the Suwa clan defied Nobutada’s forces. Because of the influence of Edo neo-Confucianism (1600–1868), the status of the onna-musha diminished significantly. T he function of onna-musha changed in accordance with that of their husbands. Samurai were no longer concerned with battles and war, but became bureaucrats. Women, specifical daughters of most upper-class households, were soon pawns to dreams of success and power. The roaring ideals of fearless devotion and selflessness were gradually replaced by quiet, passive, civil obedience. Travel during the Edo period was demanding and unsettling for many female samurai due to tight restrictions. They always had to be accompanied by a man, since they were not allowed to travel by themselves. Additionally, they had to possess specific permits establishing their business and motives. Samurai women also received much harassment from officials who manned inspection checkpoints. The onset of the 17th century marked a significant transformation in the social acceptance of women in Japan. Many samurai viewed women purely as child bearers; the concept of a woman being a fit companion for war was no longer conceivable. The relationship between a husband and wife could be correlated to that of a lord and his vassal. According to Ellis Amdur, “husbands and wives did not even customarily sleep together. The husband would visit his wife to initiate any sexual activity and afterwards would retire to his own room”. The most popular weapon-of-choice of onna-musha is the naginata, which is a versatile, conventional polearm with a curved blade at the tip. The weapon is mainly favored for its length, which can compensate for the strength and body size advantage of male opponents. The naginata has a niche between the katana and the yari, which is rather effective in close quarter melee when the opponent is kept at bay, and is also relatively efficient against cavalry. Through its use by many legendary samurai women, the naginata has become the iconic armament of the woman warrior. During the Edo period, many schools focusing on the use of the naginata were created and perpetuated its association with women. Additionally, as most of the time, their primary purpose as onna-musha was to safeguard their homes from marauders, emphasis was laid on ranged weapons to be shot from defensive structures. The image of samurai women continues to be impactful in martial arts, historical novels, books, and popular culture in general. Like kunoichi (female ninja) and geisha, the onna-musha’s conduct is seen as the ideal of Japanese women in movies, animations and TV series. In the West, the onna-musha gained popularity when the historical documentary Samurai Warrior Queens aired on the Smithsonian Channel.

(Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / Library of Congress). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe