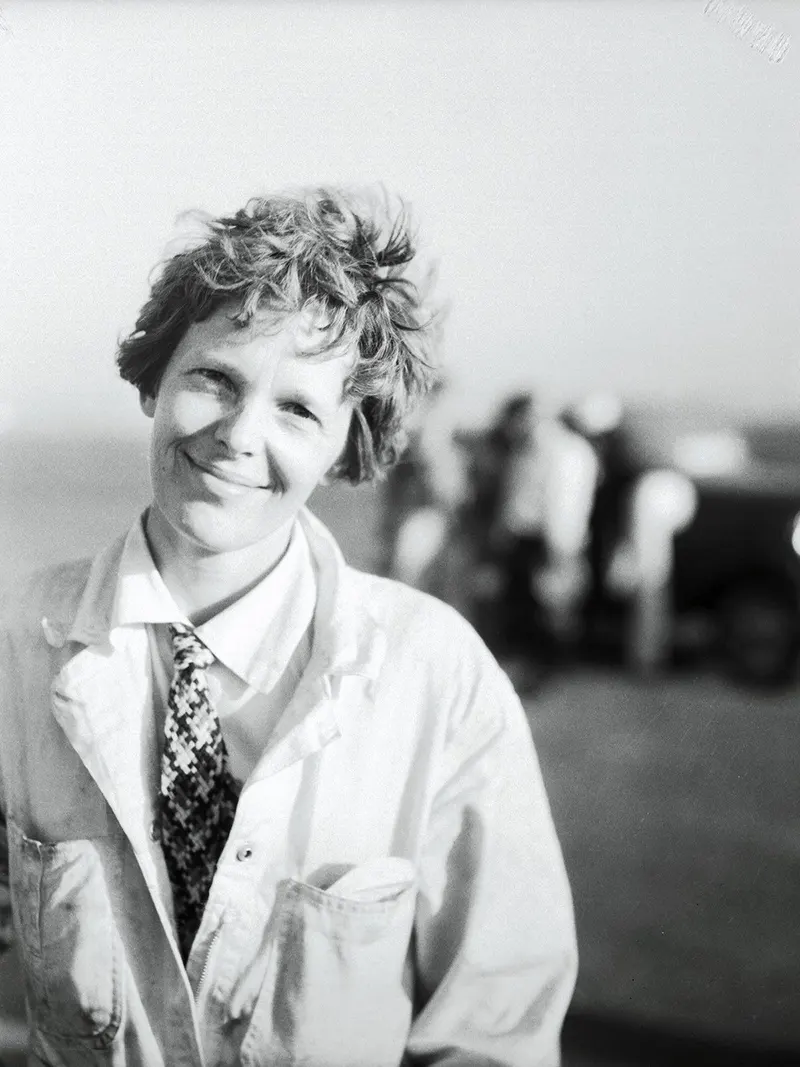

With Earhart’s death in 1937, women aviators became less prominent but continued to contribute greatly to aviation, especially as auxiliary pilots during the Second World War. In 1784, Elisabeth Thible became the first woman to fly, as a passenger in a hot air balloon. Over a century later, in 1909, women again took to the air, this time in a heavier-than-air craft. Another French woman, Elise Deroche (1889-1919), who referred to herself as a baroness although the legitimacy of the title was doubtful, became the world’s first licensed woman pilot in 1910. In the next few years, women in Germany, Italy, and America became licensed to fly, many of them explicitly trying to prove that women were as capable as men in the air. The first American woman to fly solo was Blanche Scott (1890-1970), hired by the Curtiss Airplane Company to demonstrate the safety of their airplanes. For the next six years, Scott flew in aerial exhibitions, performing stunts before excited crowds. Another woman, Bessie Coleman (1893-1926), attacked barriers of race as well as gender. Although she was not permitted to attend an American flight school because of her race, she eventually earned her pilot’s license in France, becoming the first black woman in the world to do so. Returning to the U.S. after this accomplishment, she opened a flight school in 1921. Unfortunately, she died in a plane crash just five years later. There were a number of other notable women pilots in the 1910s and 1920s, including Harriet Quimby (1884-1912; the first woman to fly across the English Channel), Ruth Law (who set a non-stop distance record for both men and women), and Katherine Stinson. Most famous, of course, was Amelia Earhart. During the Second World War, the Soviet Union put women pilots into combat, mostly flying antiquated bombers to attack German positions in Crimea. Women pilots faced similar obstacles, too, no matter in what nation they flew. All met with some degree of resistance from male pilots and, in many cases, from the airplane owners, their families, and the public. In general, this resistance stemmed from a few basic causes. Some believed that women were too weak or too slow to safely control aircraft moving at high altitudes and high speeds. Flying was considered “unfeminine,” and women who wanted to fly were suspected of being the same. Although women’s roles in the military remain more limited than those of men, women did begin to receive larger and more technical roles in World War II and in later years. In particular, women were permitted to join the military and to fly in supporting roles for the Allies. By ferrying planes from factory to air base and across to Europe, for example, women pilots freed men up for combat missions. However, women’s roles in military aviation stalled out at this point for many years in the U.S. because of continuing public, military, and governmental reluctance to place women in harm’s way. In fact, it was not until after the Persian Gulf War in the early 1990s that American women were finally permitted to fly combat aircraft in potentially hostile situations. (Photo credit: Mashable / National Air and Space Museum Archives, Smithsonian Institution / Wikimedia Commons / Article based on The First Women Aviators by P. Andrew Karam). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe