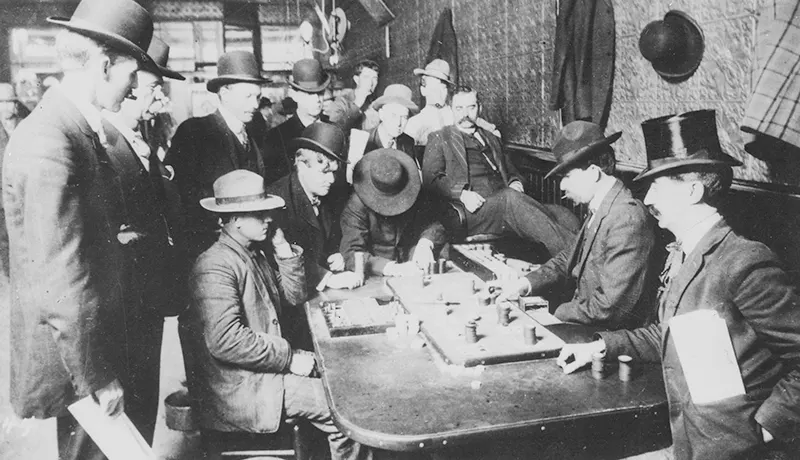

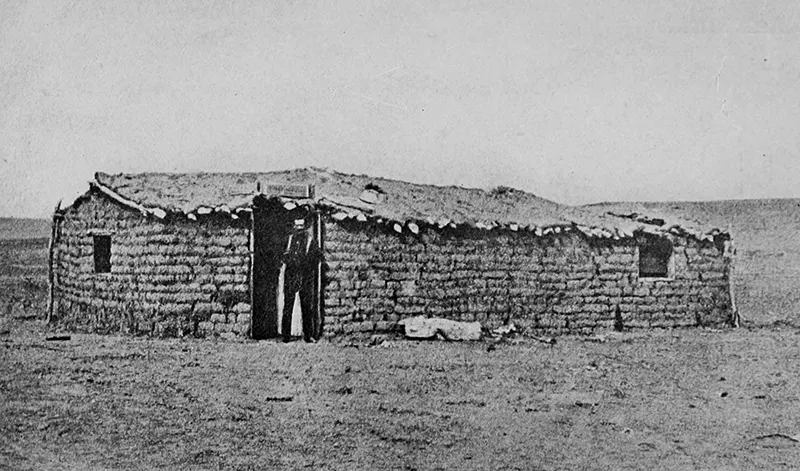

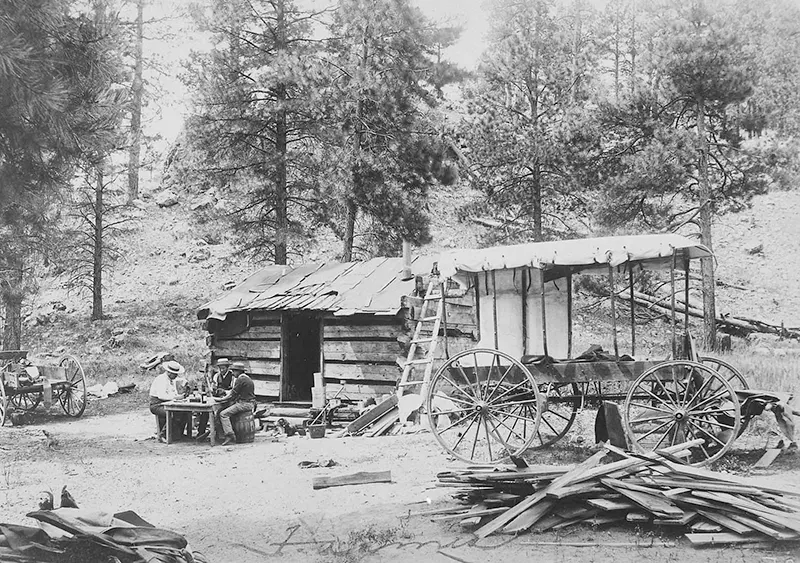

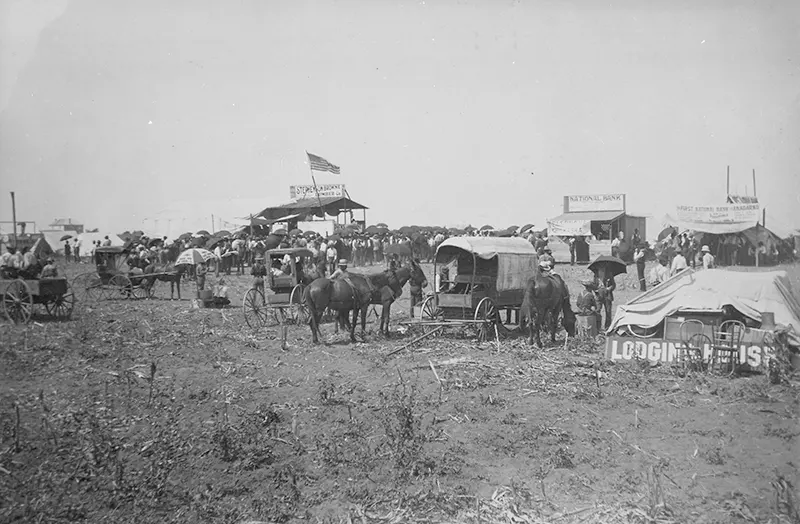

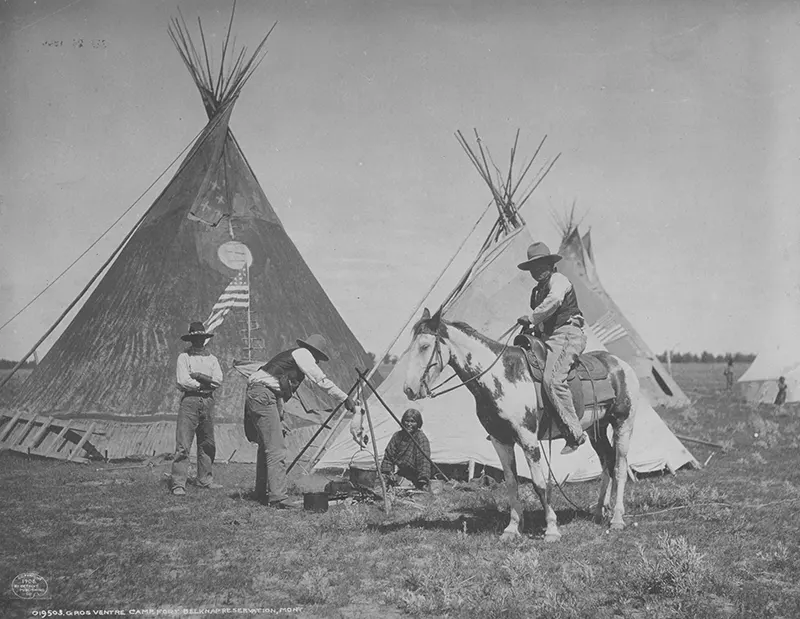

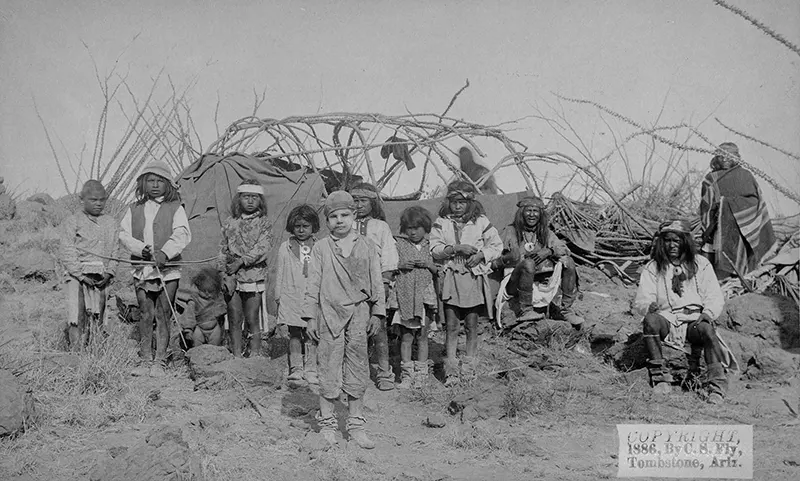

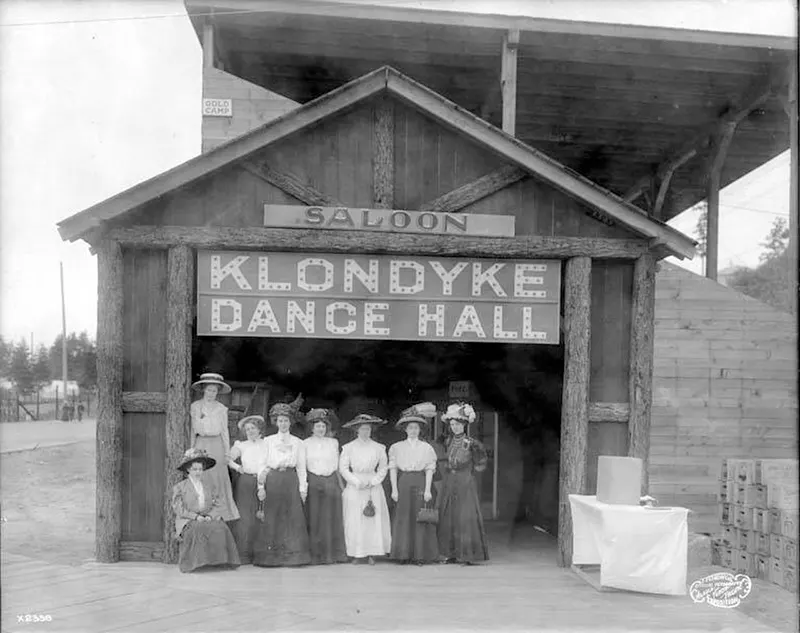

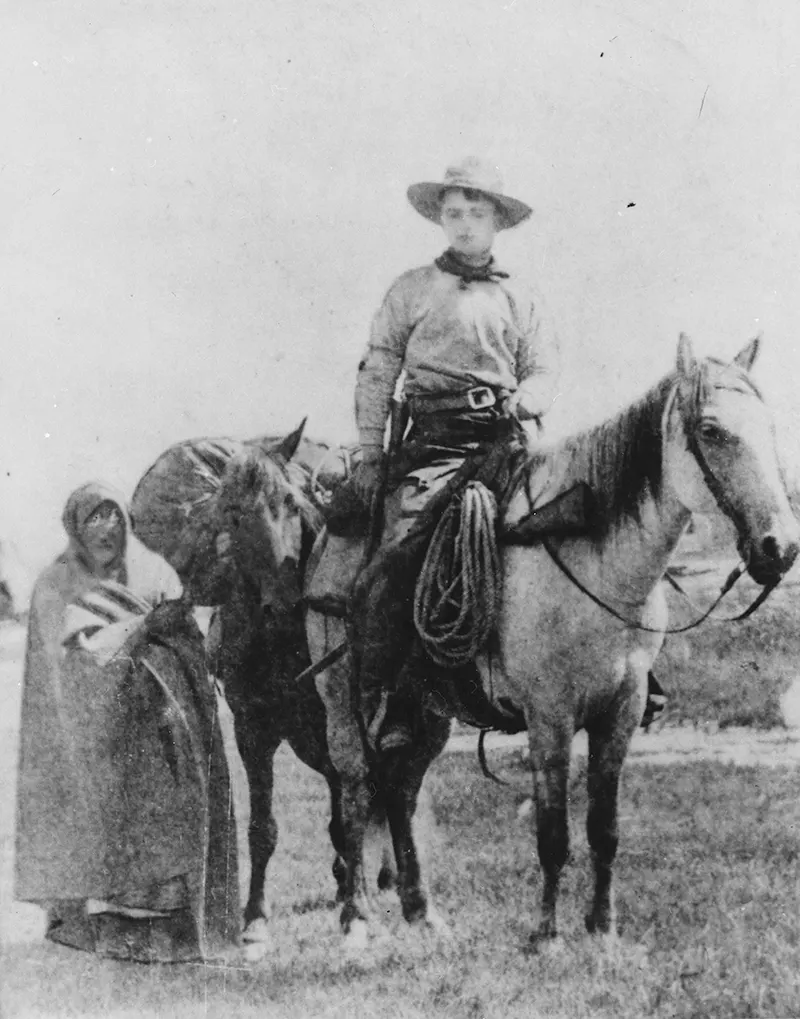

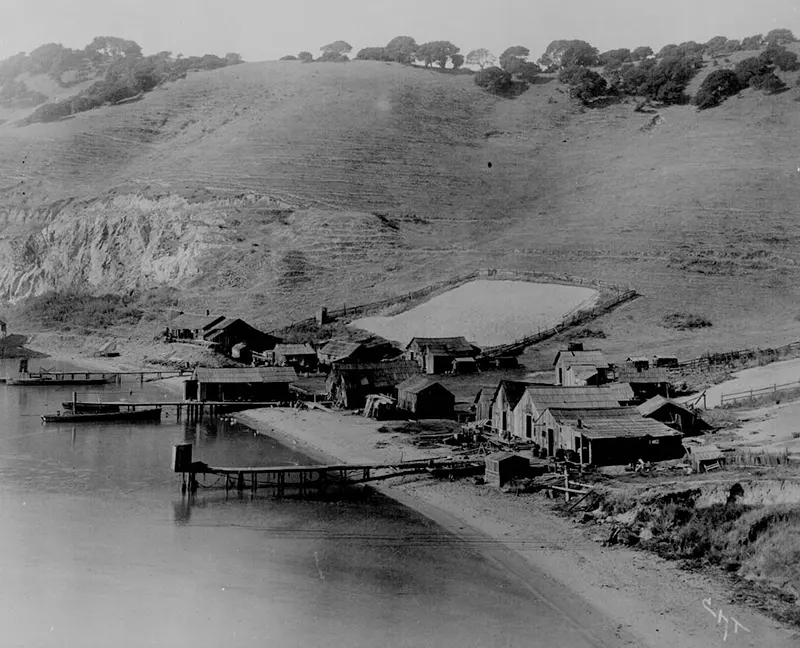

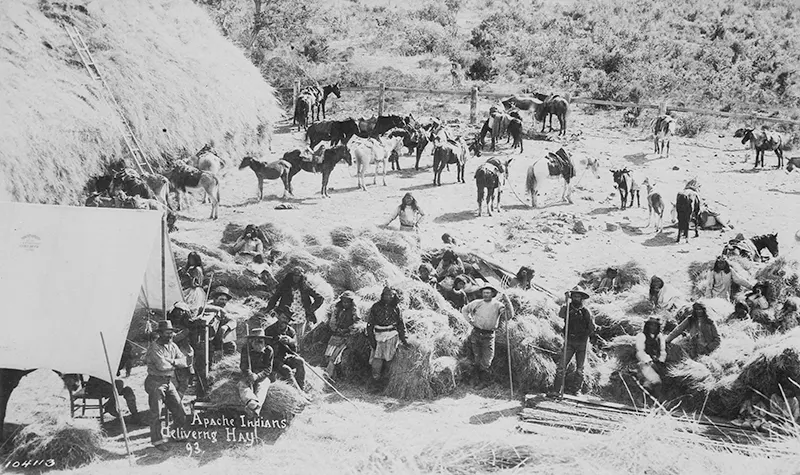

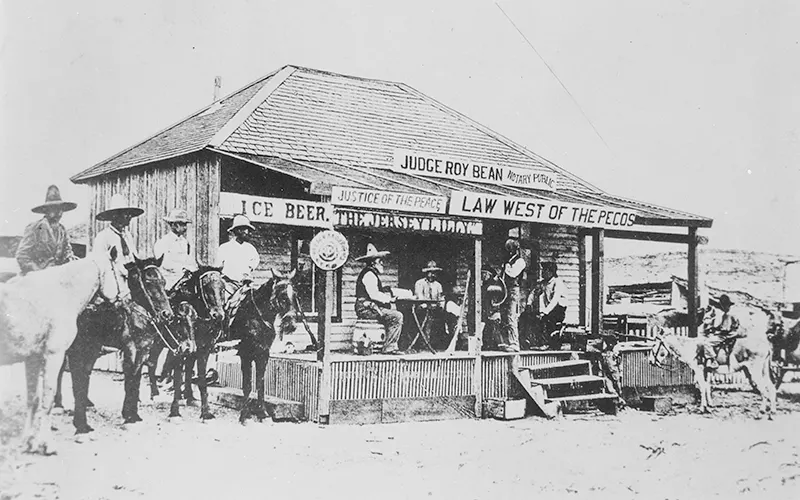

The archetypical Old West period is generally accepted by historians to have occurred between the end of the American Civil War in 1865 until the closing of the frontier by the Census Bureau in 1890. A frontier is a zone of contact at the edge of a line of settlement. Leading theorist Frederick Jackson Turner went deeper, arguing that the frontier was the scene of a defining process of American civilization: “The frontier,” he asserted, “promoted the formation of a composite nationality for the American people.” He theorized it was a process of development: “This perennial rebirth, this fluidity of American life, this expansion westward…furnish[es] the forces dominating American character.” Turner’s ideas since 1893 have inspired generations of historians (and critics) to explore multiple individual American frontiers, but the popular folk frontier concentrates on the conquest and settlement of Native American lands west of the Mississippi River, in what is now the Midwest, Texas, the Great Plains, the Rocky Mountains, the Southwest, and the West Coast. As defined by Hine and Faragher, “frontier history tells the story of the creation and defense of communities, the use of the land, the development of crops and hotels, and the formation of states.” They explain, “It is a tale of conquest, but also one of survival, persistence, and the merging of peoples and cultures that gave birth and continuing life to America.” Turner himself repeatedly emphasized how the availability of free land to start new farms attracted pioneering Americans: “The existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward, explain American development.” Through treaties with foreign nations and native tribes, political compromise, military conquest, the establishment of law and order, the building of farms, ranches, and towns, the marking of trails and digging of mines, and the pulling in of great migrations of foreigners, the United States expanded from coast to coast. In his “Frontier Thesis” (1893), Turner theorized that the frontier was a process that transformed Europeans into a new people, the Americans, whose values focused on equality, democracy, and optimism, as well as individualism, self-reliance, and even violence. Settlement from the East transformed the Great Plains. The huge herds of American bison that roamed the plains were almost wiped out, and farmers plowed the natural grasses to plant wheat and other crops. The cattle industry rose in importance as the railroad provided a practical means for getting the cattle to market. The loss of the bison and growth of white settlement drastically affected the lives of the Native Americans living in the West. In the conflicts that resulted, the Native Americans, despite occasional victories, seemed doomed to defeat by the greater numbers of settlers and the military force of the U.S. government. By the 1880s, most Natives had been confined to reservations, often in areas of the West that appeared least desirable to white settlers. The cowboy became the symbol for the West in the late 19th century, often depicted in popular culture as a glamorous or heroic figure. The stereotype of the heroic white cowboy is far from true, however. The first cowboys were Spanish vaqueros, who had introduced cattle to Mexico centuries earlier. Black cowboys also rode the range. Furthermore, the life of the cowboy was far from glamorous, involving long, hard hours of labor, poor living conditions, and economic hardship. The cities played an essential role in the development of the frontier, as transportation hubs, financial and communications centers, and providers of merchandise, services, and entertainment. As the railroads pushed westward into the unsettled territory after 1860, they built service towns to handle the needs of railroad construction crews, train crews, and passengers who ate meals at scheduled stops. In most of the South, there were very few cities of any size for miles around, and this pattern held for Texas as well, so railroads did not arrive until the 1880s. They then shipped the cattle out and cattle drives became short-distance affairs. However, the passenger trains were often the targets of armed gangs. European immigrants often built communities of similar religious and ethnic backgrounds. For example, many Finns went to Minnesota and Michigan, Swedes and Norwegians to Minnesota and the Dakotas, Irish to railroad centers along the transcontinental lines, Volga Germans to North Dakota, and German Jews to Portland, Oregon. African Americans moved West as soldiers, as well as cowboys, farmhands, saloon workers, cooks, and outlaws. The Buffalo Soldiers were soldiers in the all-black 9th and 10th Cavalry regiments, and 24th and 25th Infantry Regiments of the U.S. Army. They had white officers and served in numerous western forts. About 4,000 black people came to California during the Gold Rush days. In 1879, after the end of Reconstruction in the South, several thousand Freedmen moved from Southern states to Kansas. Known as the Exodusters, they were lured by the prospect of good, cheap Homestead Law land and better treatment. The all-black town of Nicodemus, Kansas, which was founded in 1877, was an organized settlement that predates the Exodusters but is often associated with them. As the American frontier passed into history, the myths of the West in fiction and film took a firm hold in the imaginations of Americans and foreigners alike. In David Murdoch’s view, America is exceptional in choosing its iconic self-image: “No other nation has taken a time and place from its past and produced a construct of the imagination equal to America’s creation of the West.” (Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / National Archives / Library of Congress / Wikipedia / Pinterest / Flickr). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe