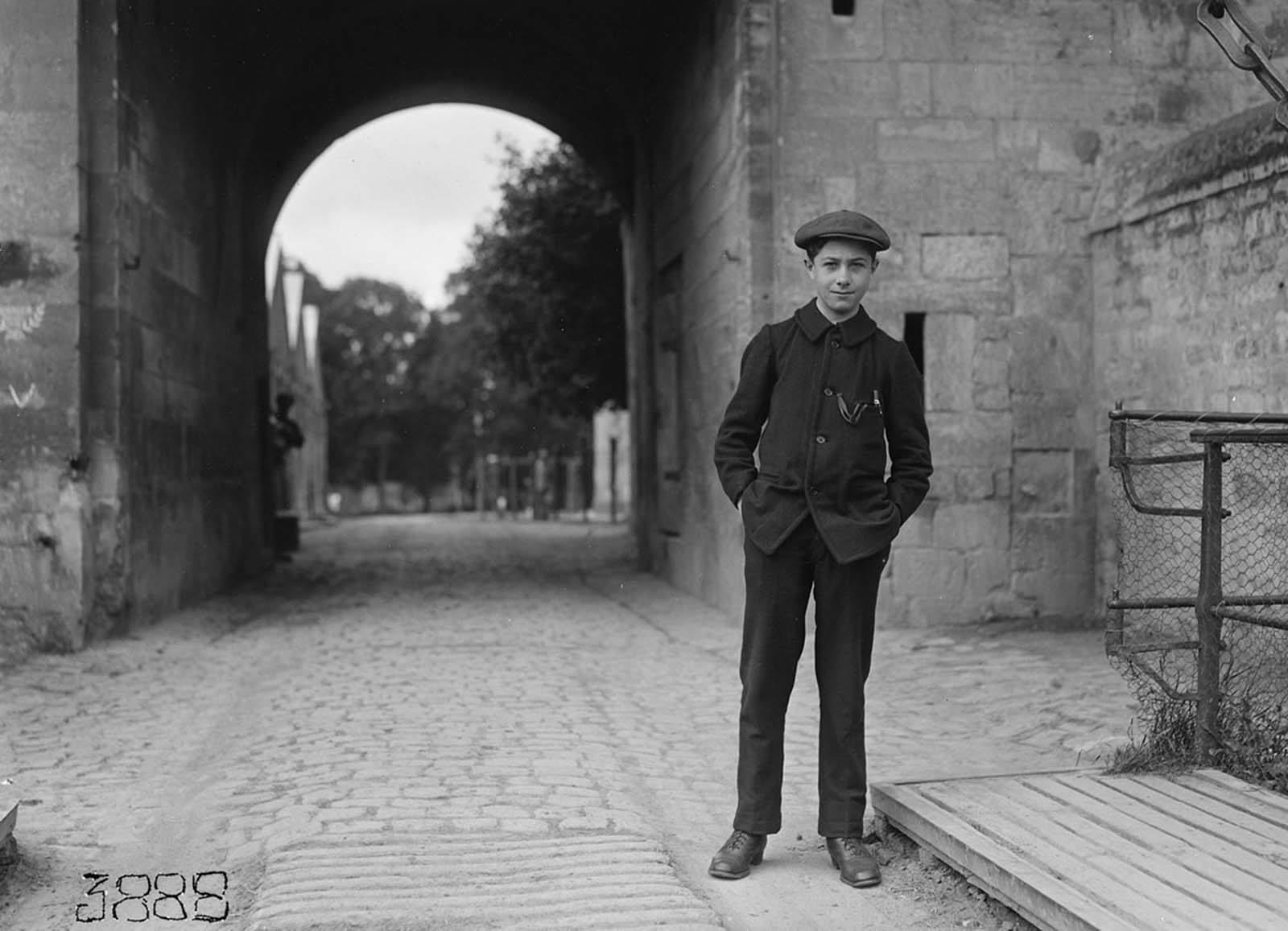

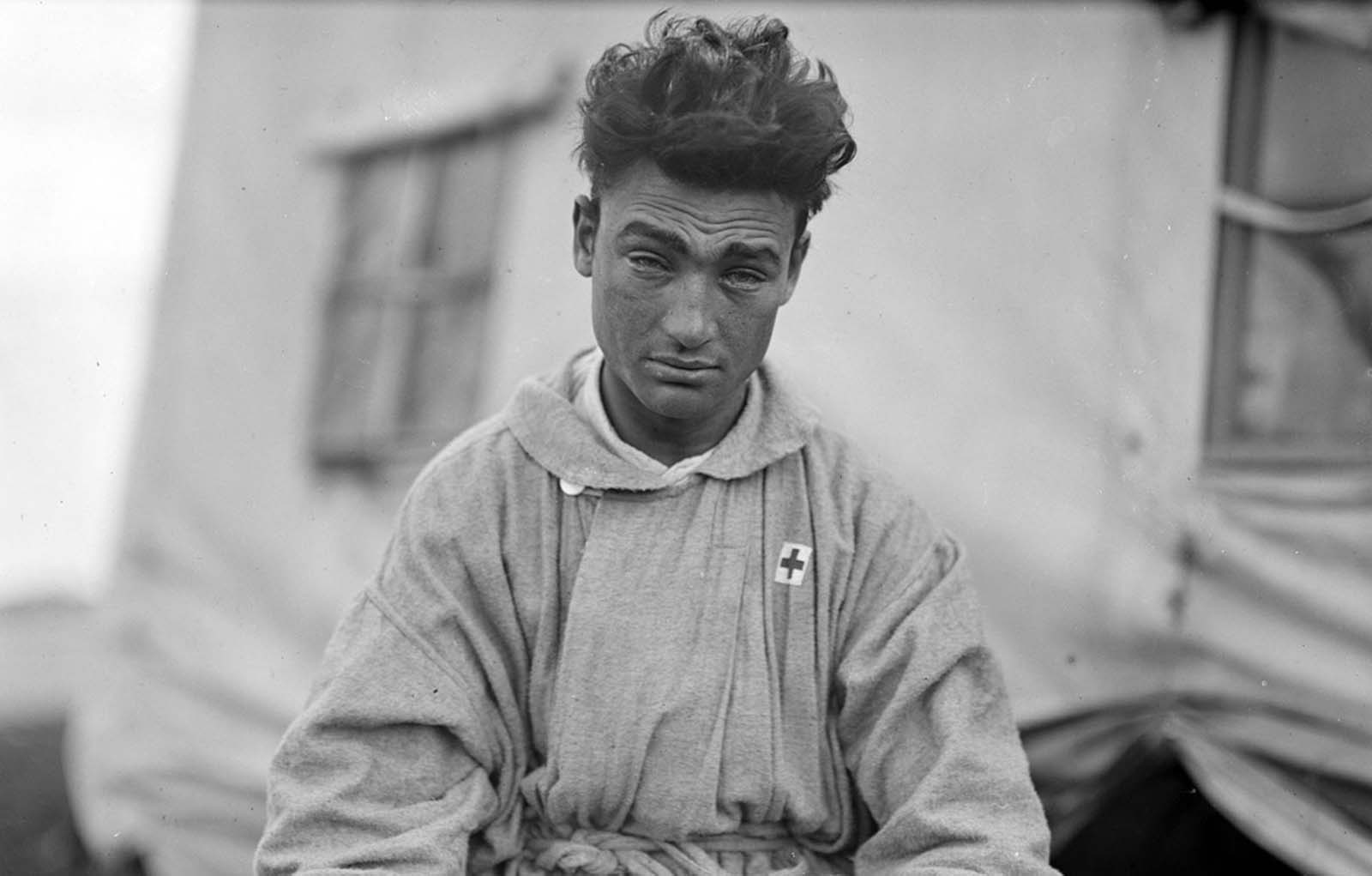

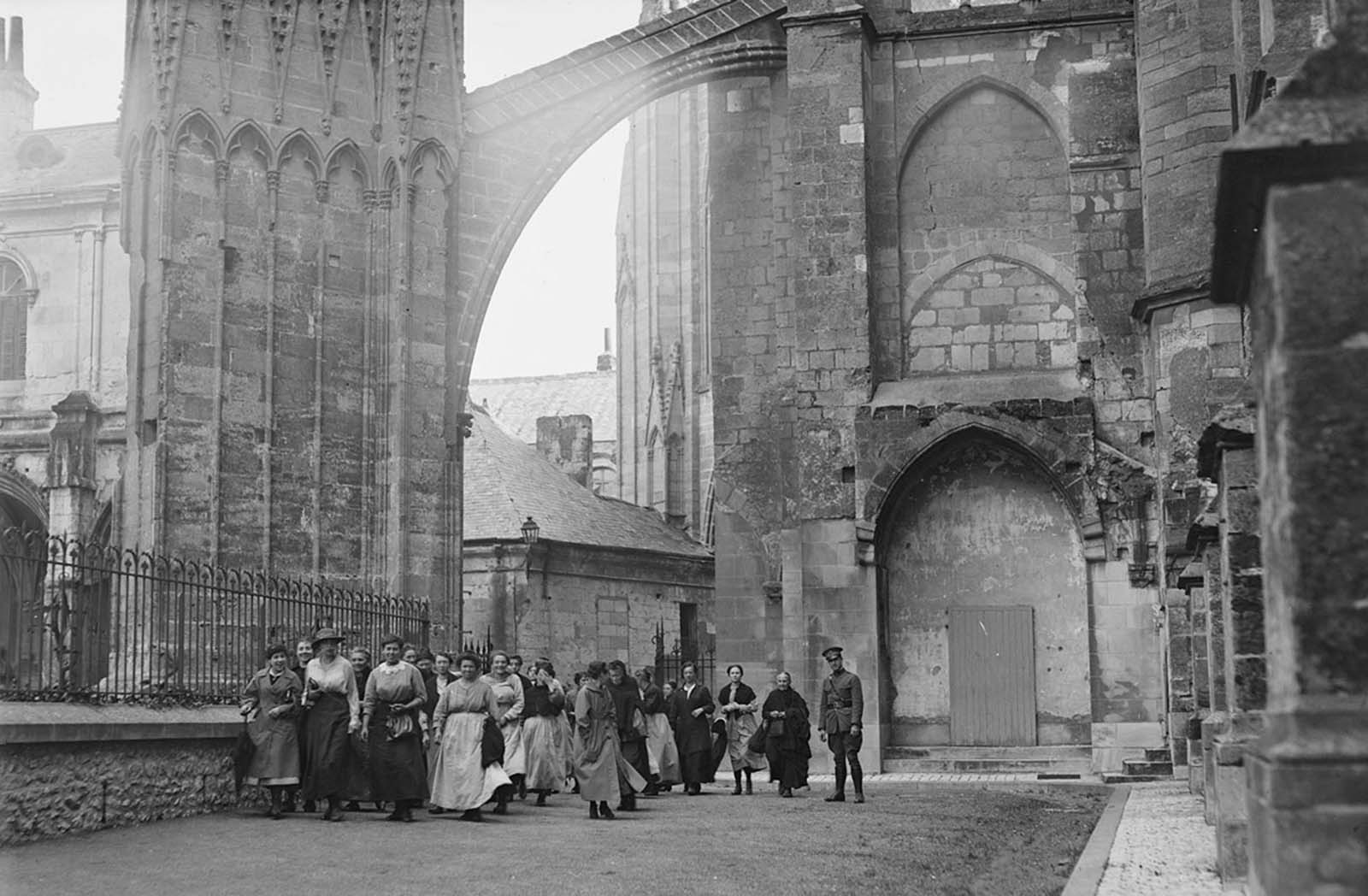

It’s 1918 and France was caught in the final year of World War I. American photographer Lewis Hine traveled across the country for the American Red Cross, documenting their work with refugees, orphans, and wounded soldiers. Lost for decades, his poignant work has recently been made public by the Library of Congress. Lewis Hine has been acknowledged as one of America’s principal 20th-century photographers, best known for his moving portraits of immigrants on Ellis Island, child laborers in factories and mines, and steelworkers balanced on high girders of the Empire State Building. In World War I, Hine became a photographer for the Red Cross, assigned to record the devastation in Europe and document the need for relief work. In the spring and summer of 1918, he photographed hundreds of war refugees, orphaned children, hospitalized U.S. soldiers, nurses, and volunteers, as well as the country’s ruins. The photographs were intended to drum up support for the Red Cross and appeal to an American audience. Some of these pictures appeared in Red Cross publications, but most of them went into the organization’s archives, where they remained hidden for almost 100 years. At the end of World War II, the Red Cross deposited its photograph collection — some 50,000 images — at the Library of Congress, where Hine’s work was ”lost” due to an eccentric filing code that baffled historians for nearly 40 years. Author Daile Kaplan was finally able to break the code, identify Hine’s photographs, and reintroduce to the world the best of this master’s “lost” photographs, giving him his due, at last, as a true pioneer of photojournalism. (Photo credit: Lewis Wickes Hine / Library of Congress). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe