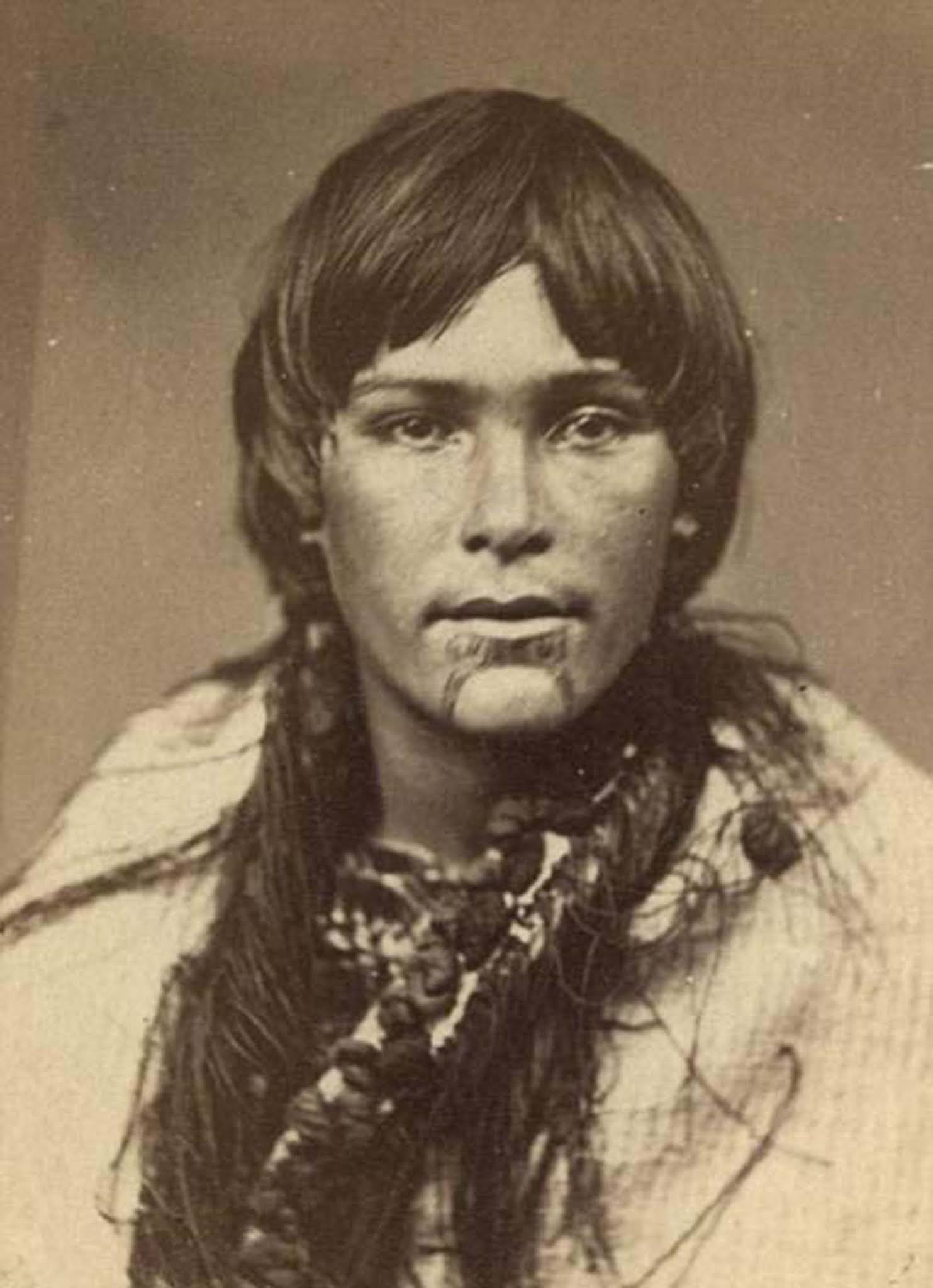

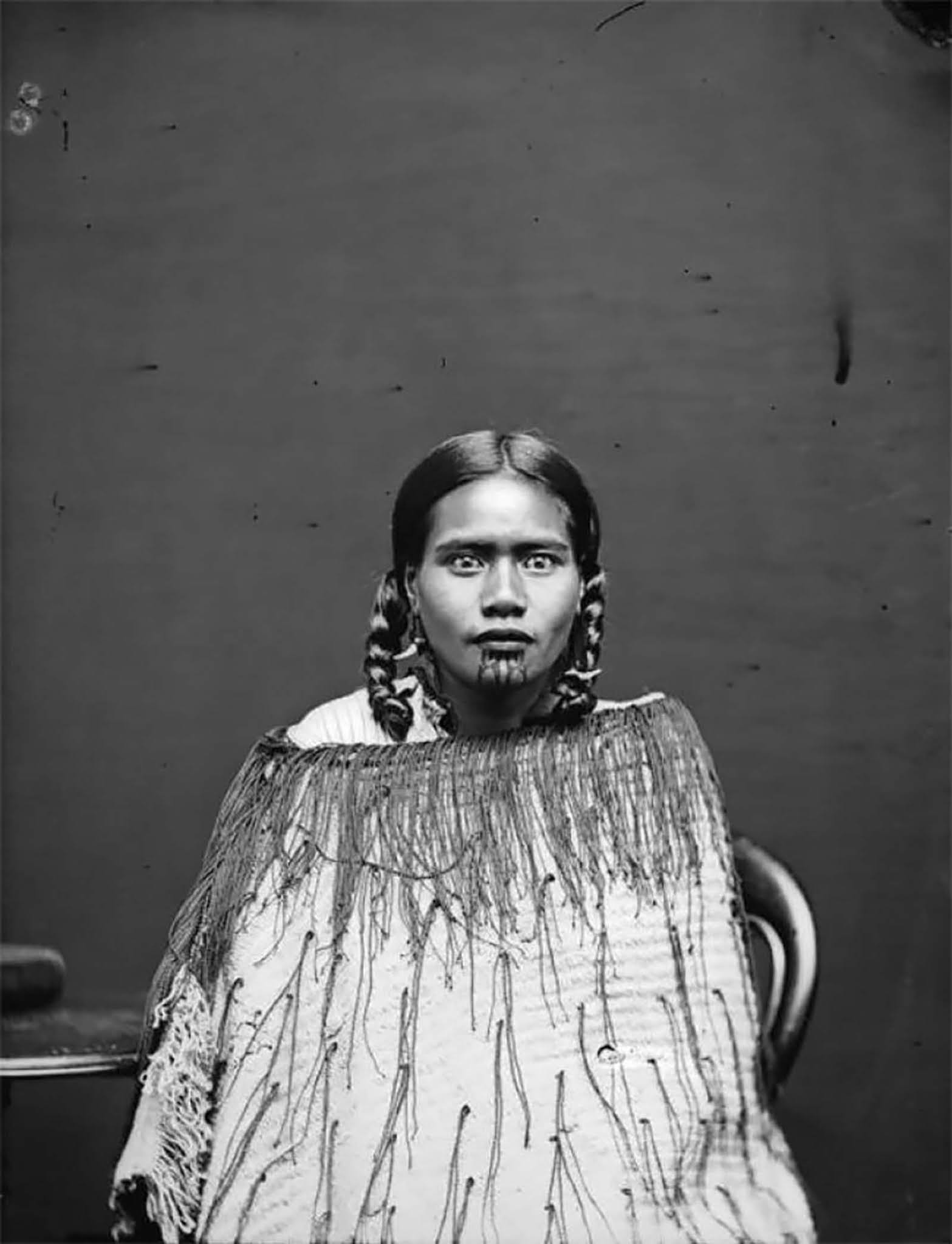

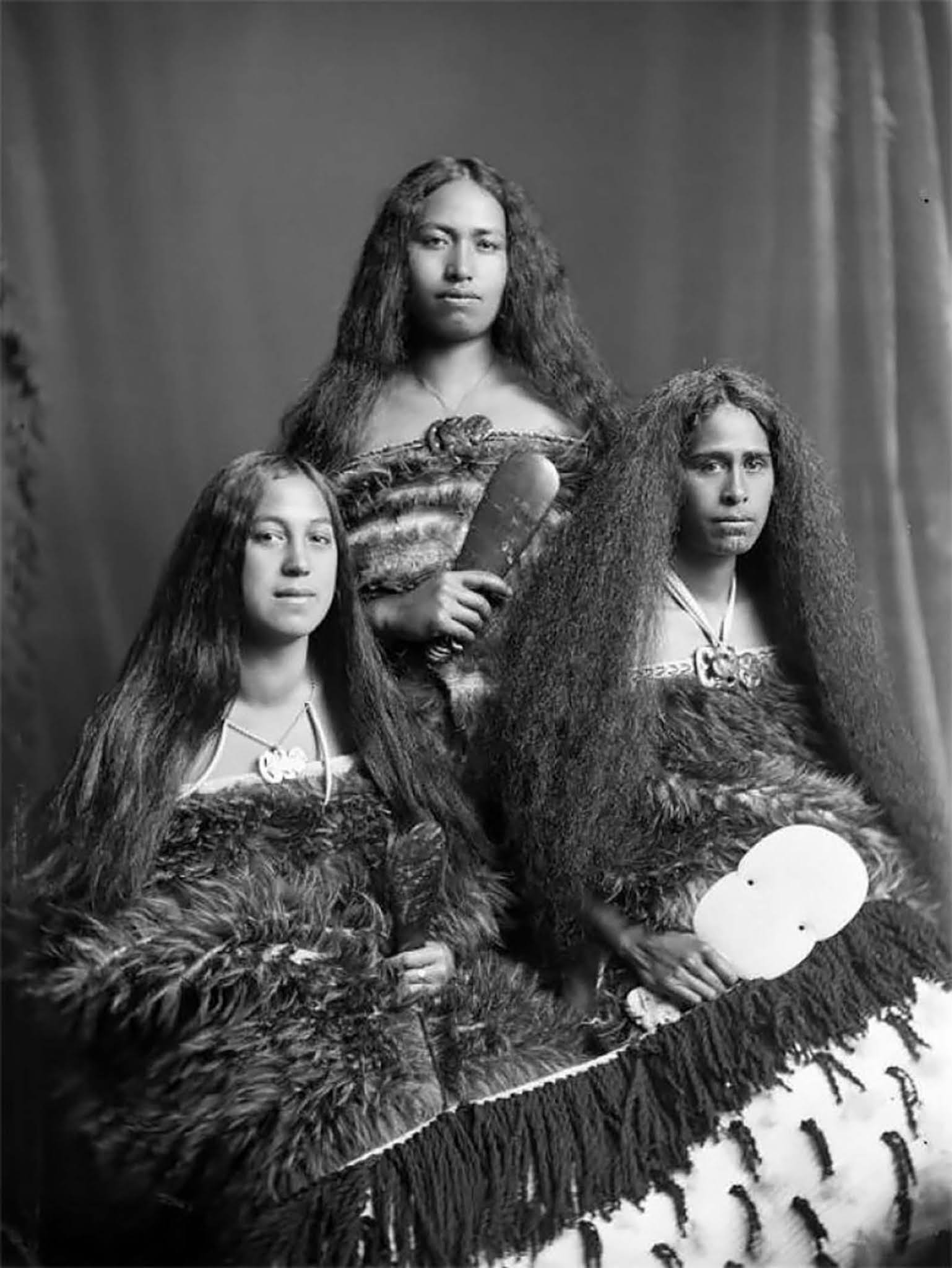

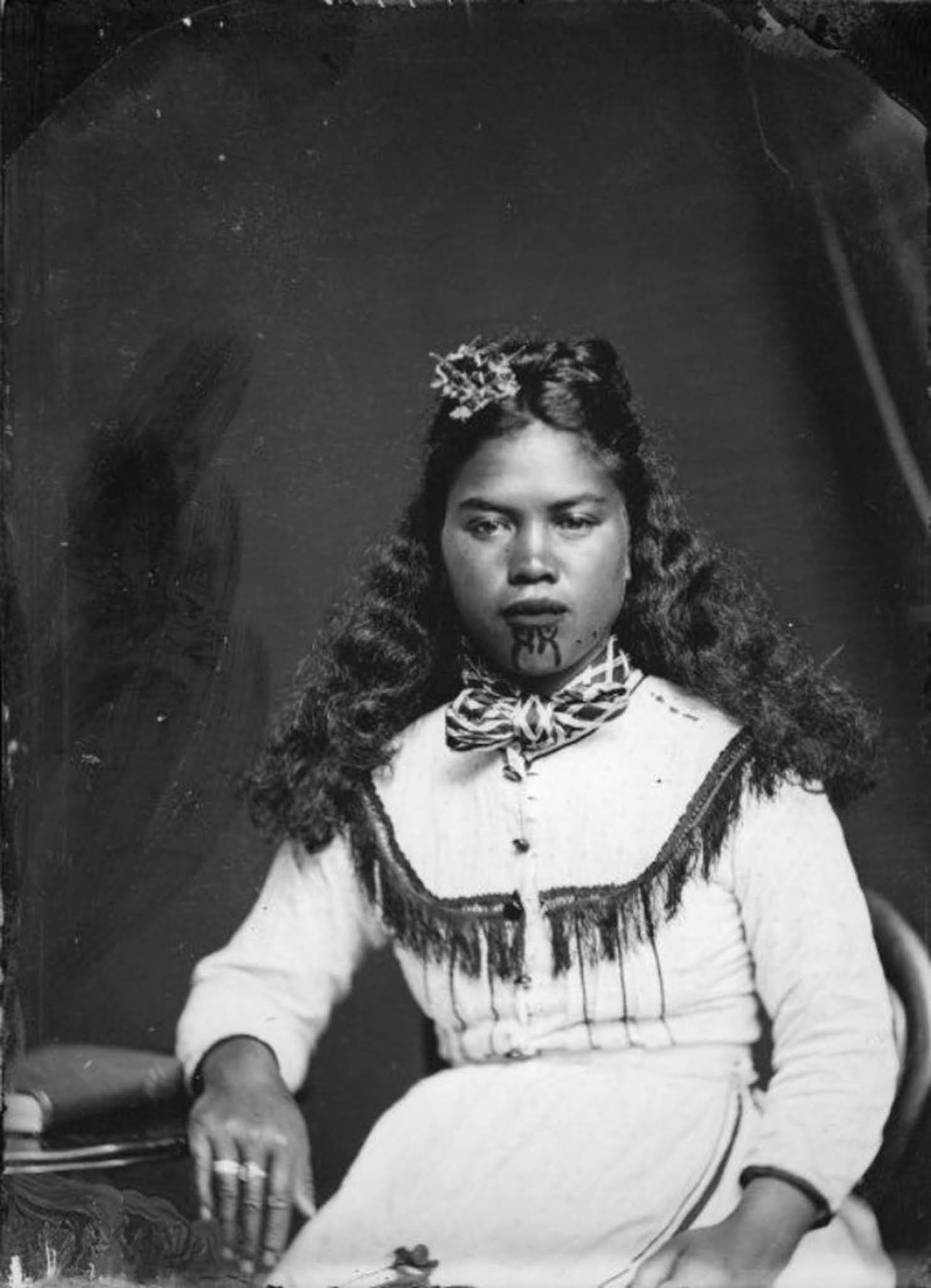

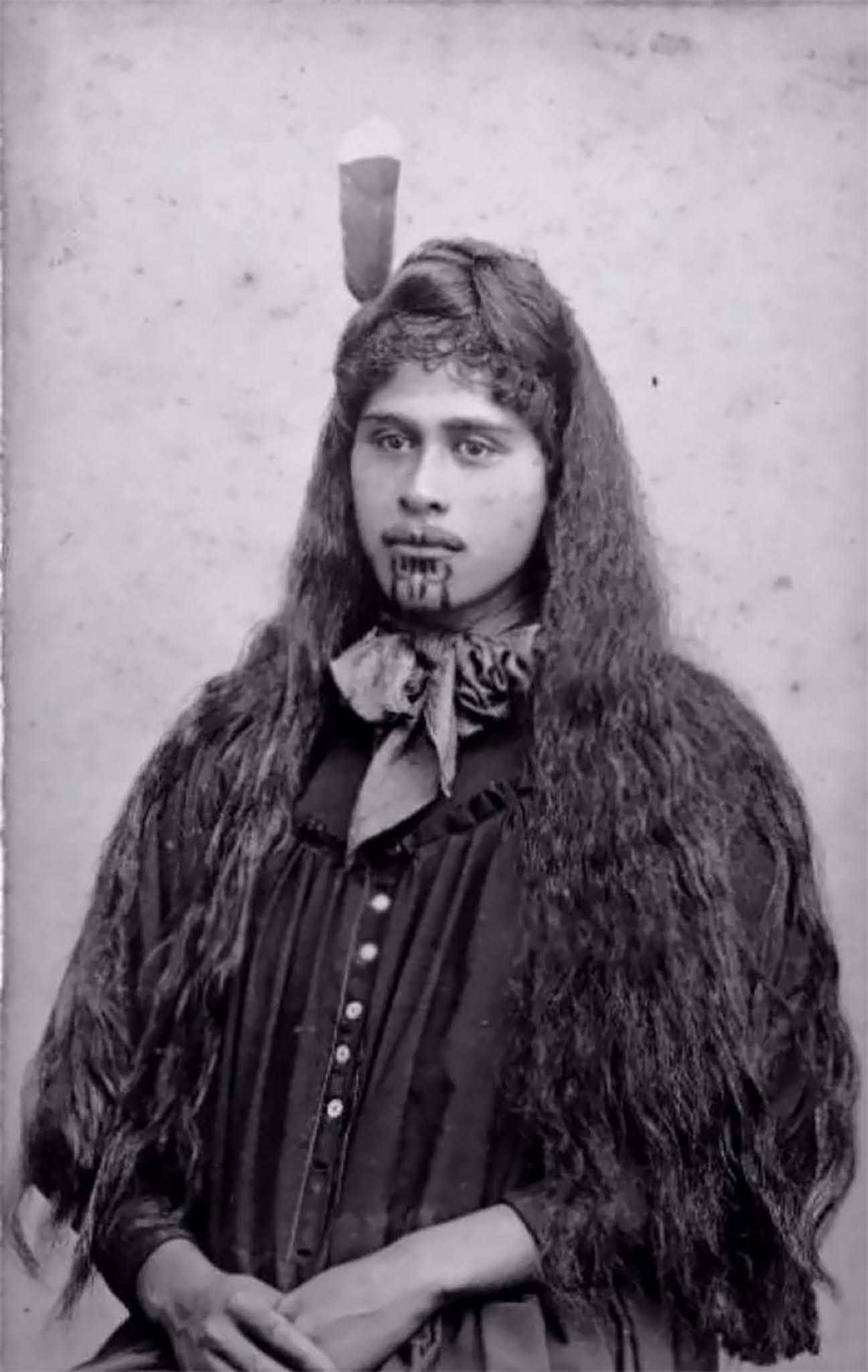

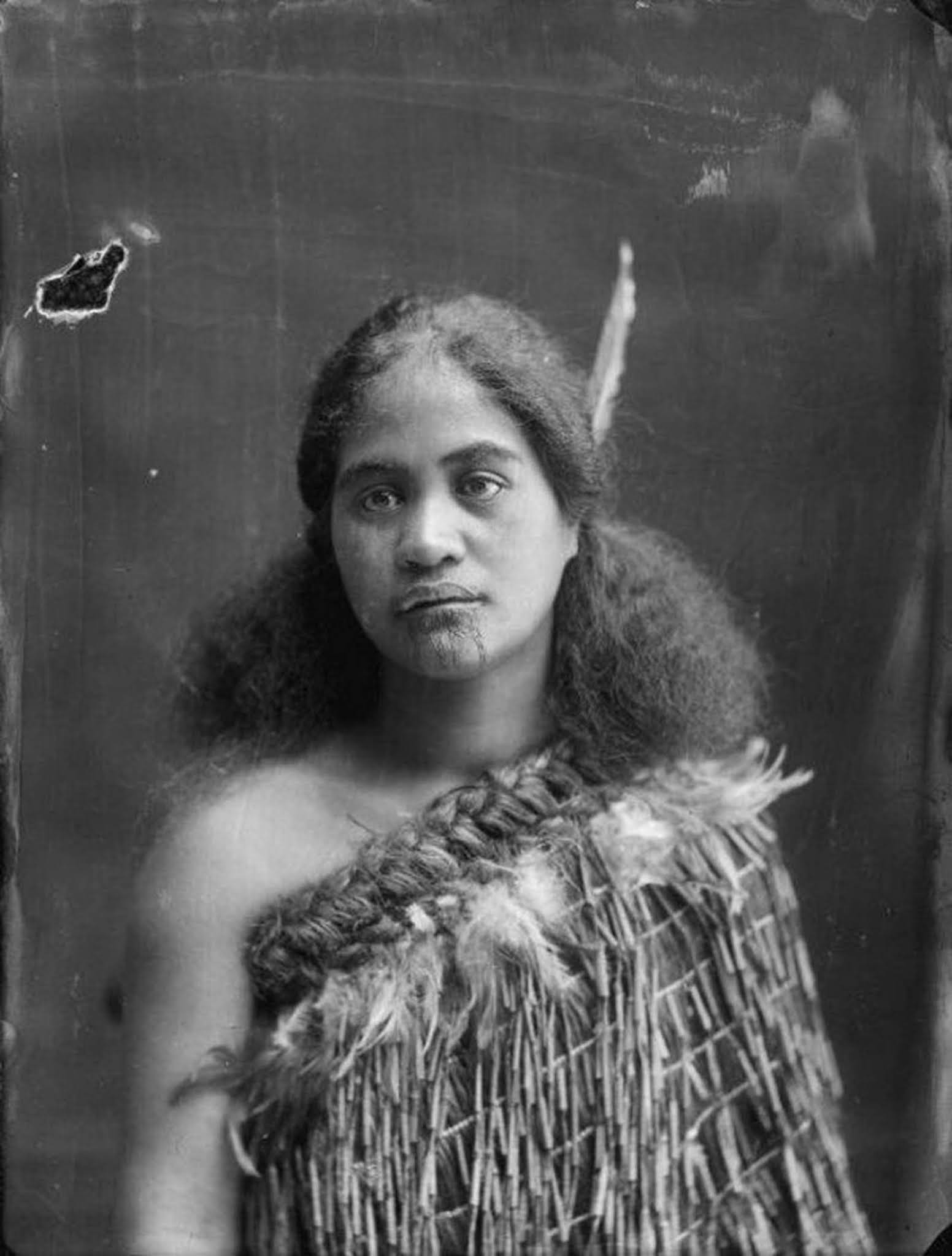

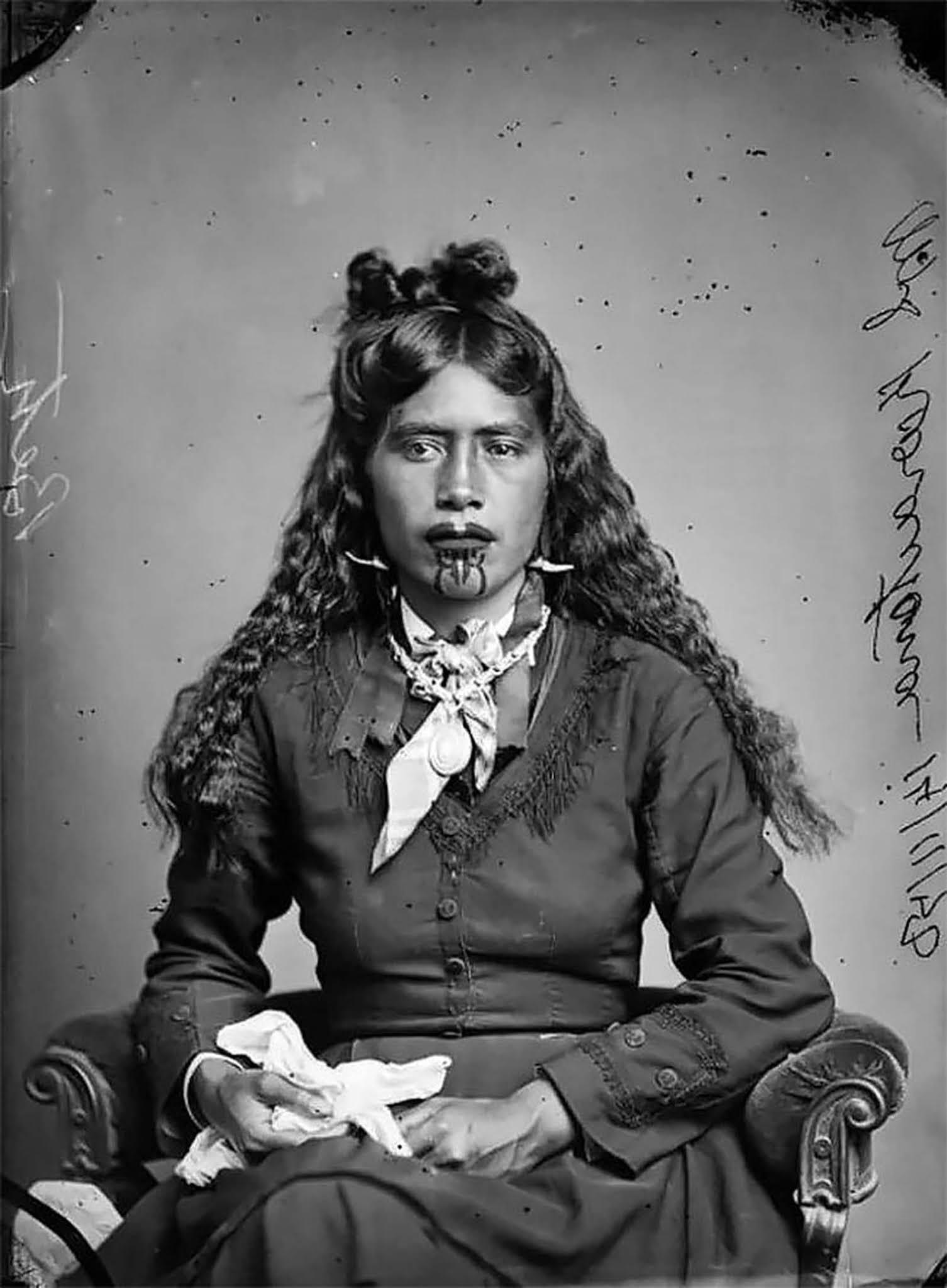

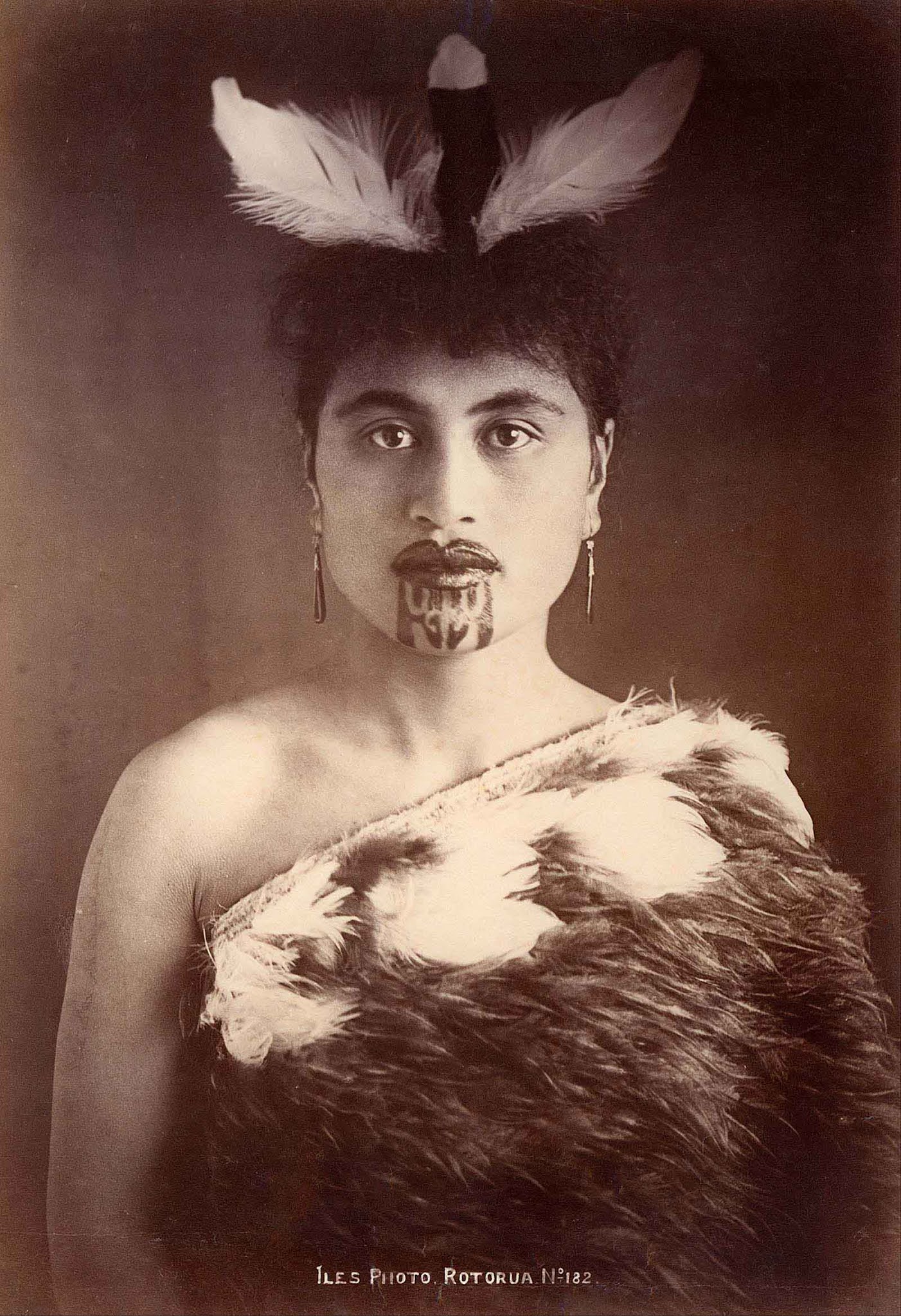

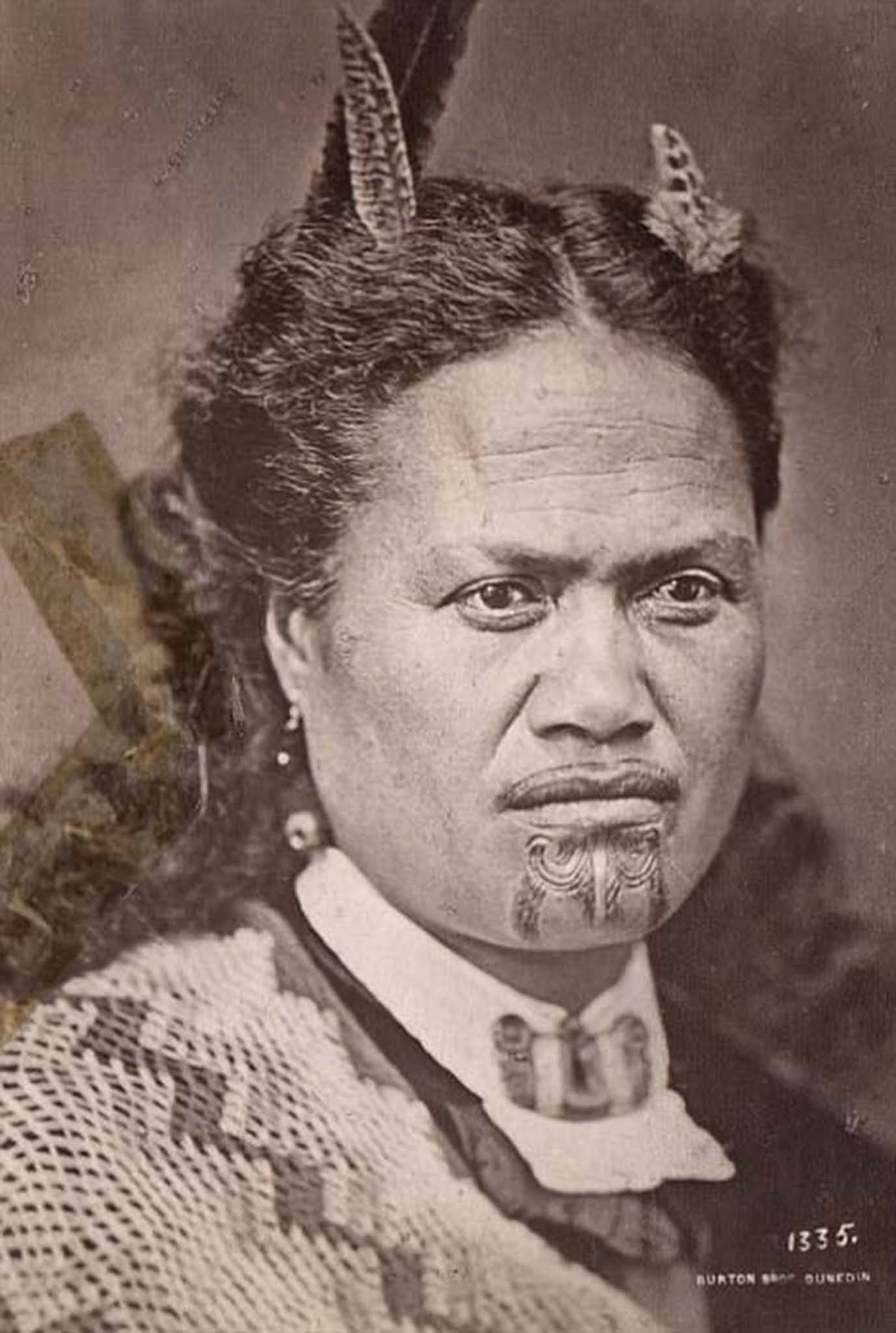

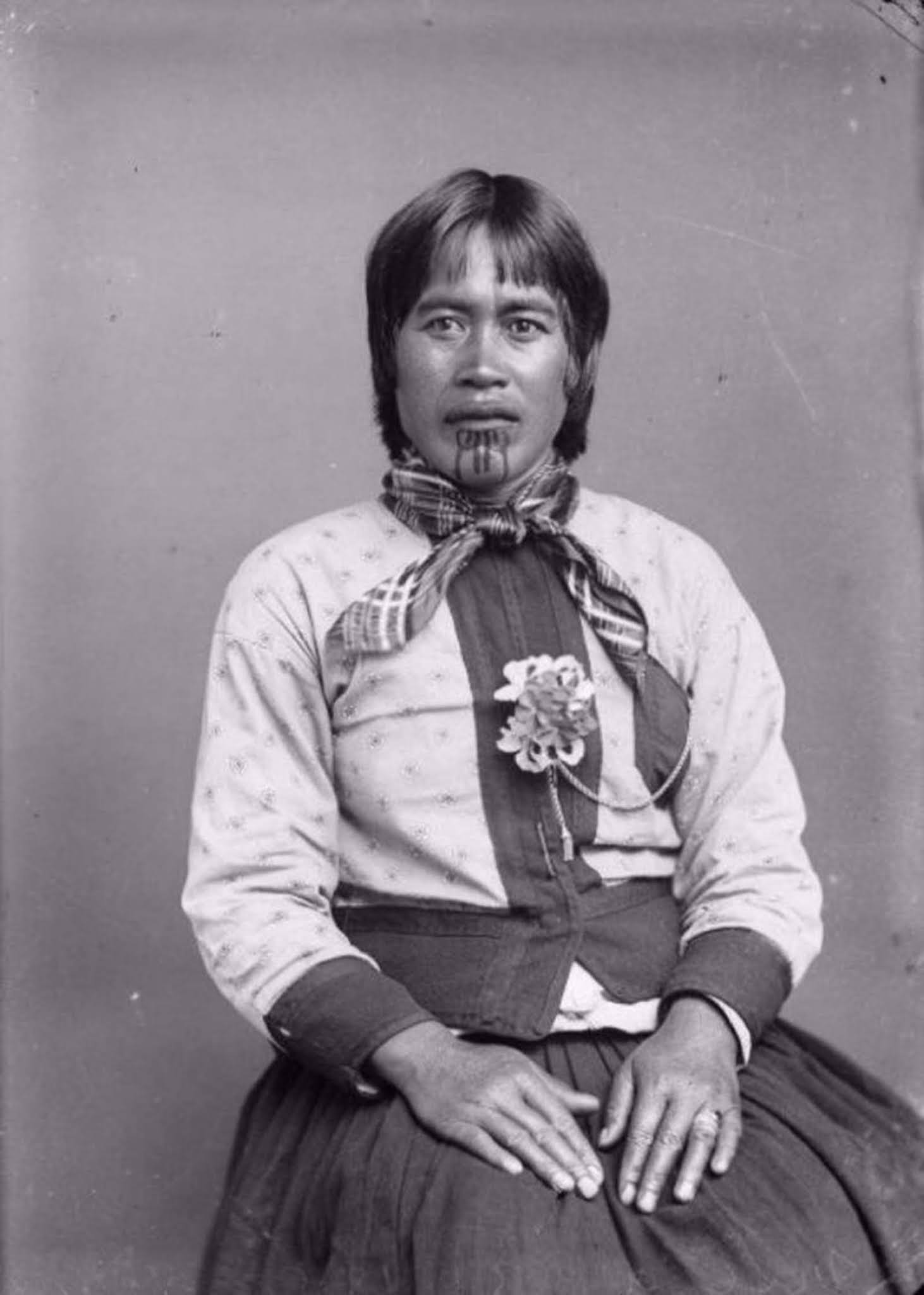

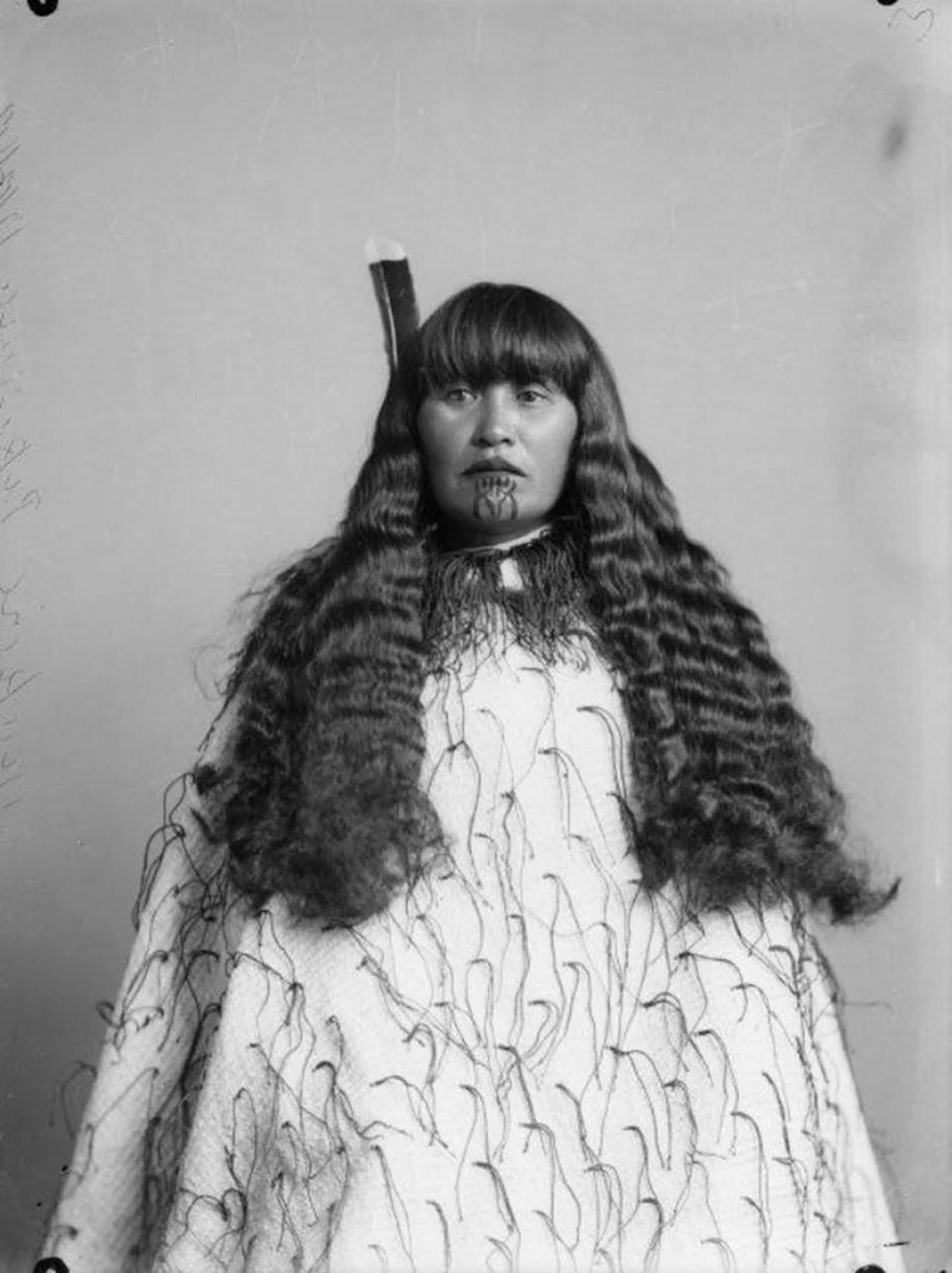

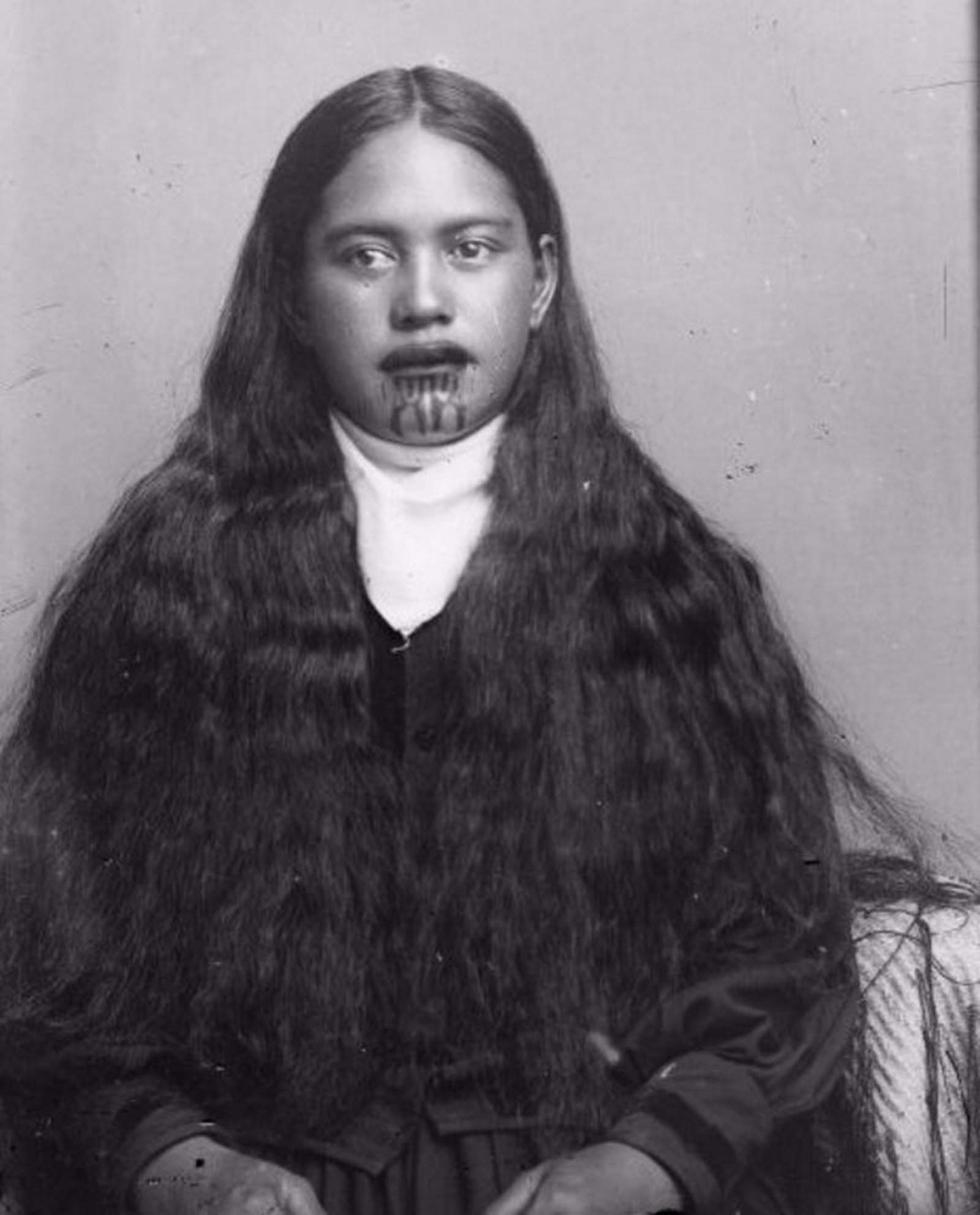

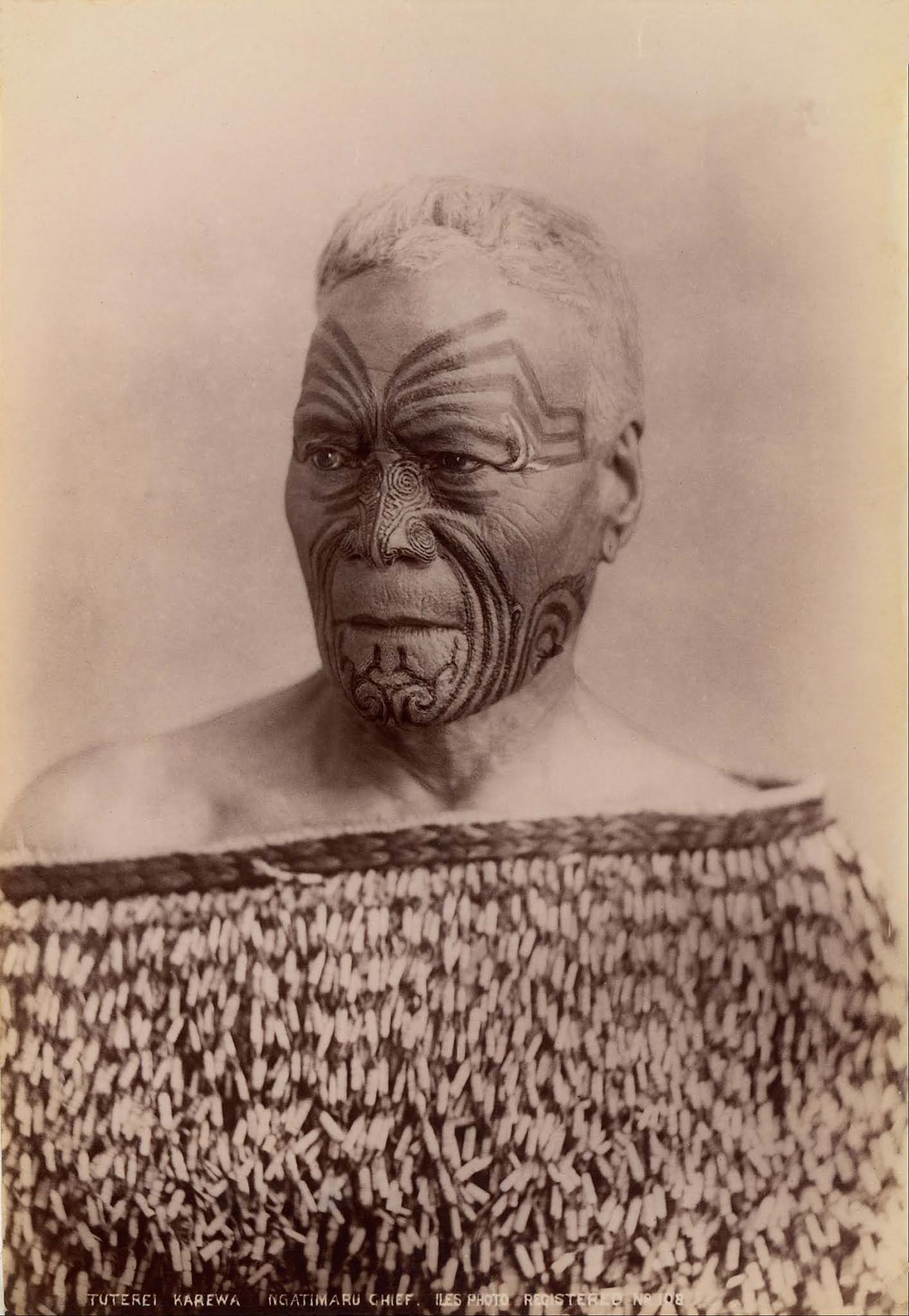

The tattoos depicted the story of the wearer’s family, their ancestral tribe, and their position within that group. Moko were associated with mana and high social status; however, some very high-status individuals were considered too tapu to acquire moko, and it was also not considered suitable for some tohunga to do so. Receiving moko constituted an important milestone between childhood and adulthood, and was accompanied by many rites and rituals. Apart from signaling status and rank, another reason for the practice in traditional times was to make a person more attractive to the opposite sex. Men generally received moko on their faces, buttocks (raperape) and thighs (puhoro). Women usually wore moko on their lips (kauwae) and chins. Other parts of the body known to have moko include women’s foreheads, buttocks, thighs, necks, and backs, and men’s backs, stomachs, and calves. While its exact origins are unknown, the art of ta moko came from Eastern Polynesian culture. Before the needle was introduced, ta moko instruments consisted of uhi chisels made of bone that would carve directly into the skin, leaving grooves rather than smooth skin. As such, the ta moko process was long and painful, taking as long as a year for a piece to be completed. The pigment used in tā moko was usually made from charcoal mixed with oil or liquid from plants. Known as wai ngārahu, it was stored in special containers. Women continued receiving moko through the early 20th century, and the historian Michael King in the early 1970s interviewing over 70 elderly women who would have been given the moko before the 1907 Tohunga Suppression Act. Women were traditionally only tattooed on their lips, around the chin, and sometimes the nostrils.

After the Brits colonized New Zealand, ta moko declined as a cultural form. This was partly due to the Tohunga Suppression Act of 1907, which outlawed Māori medical practices. As these were closely linked to Māori spiritual and cultural traditions, the Māoris lost much of their culture and became what was termed as a “lost race.” The Act was eventually repealed in 1962. Since the 1990s, there has been a resurgence of the practice of ta moko for both men and women as a sign of their cultural Maori identity.

(Photo credit: News Dog Media / NZ Archives / Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe