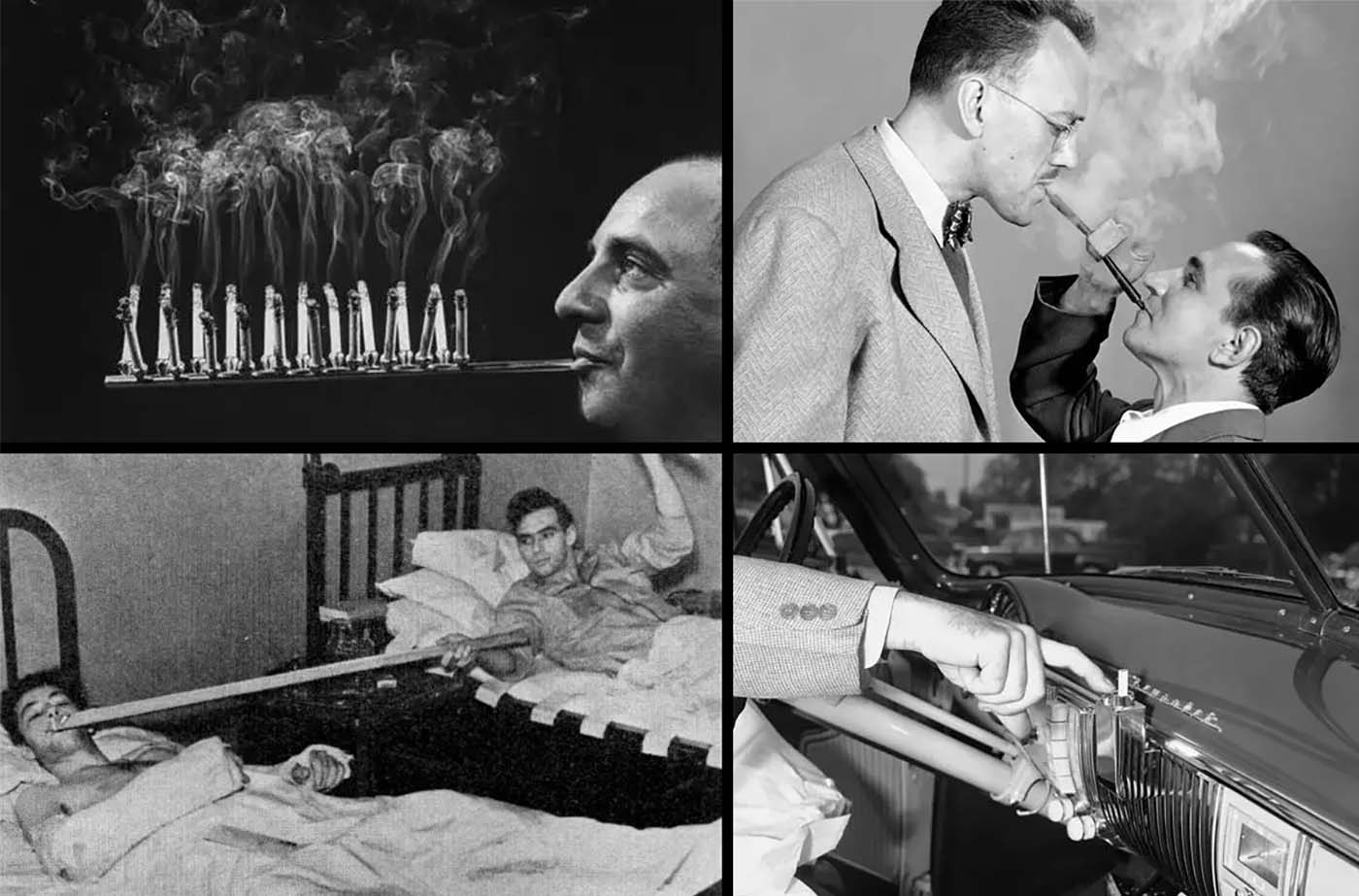

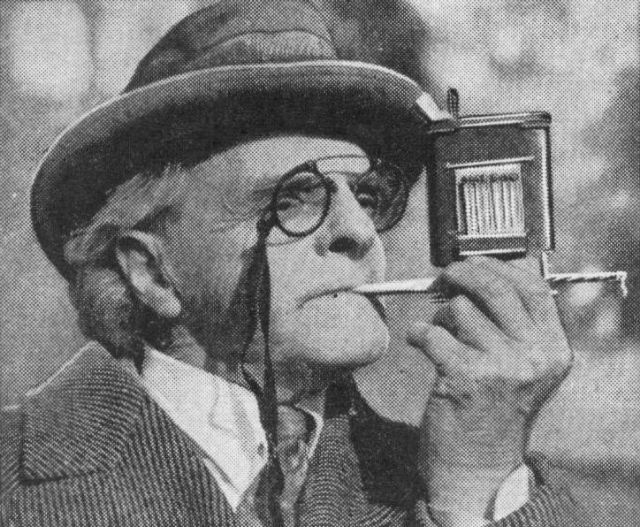

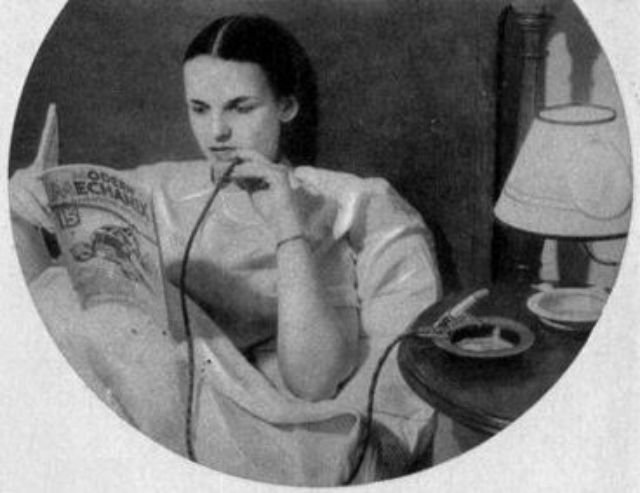

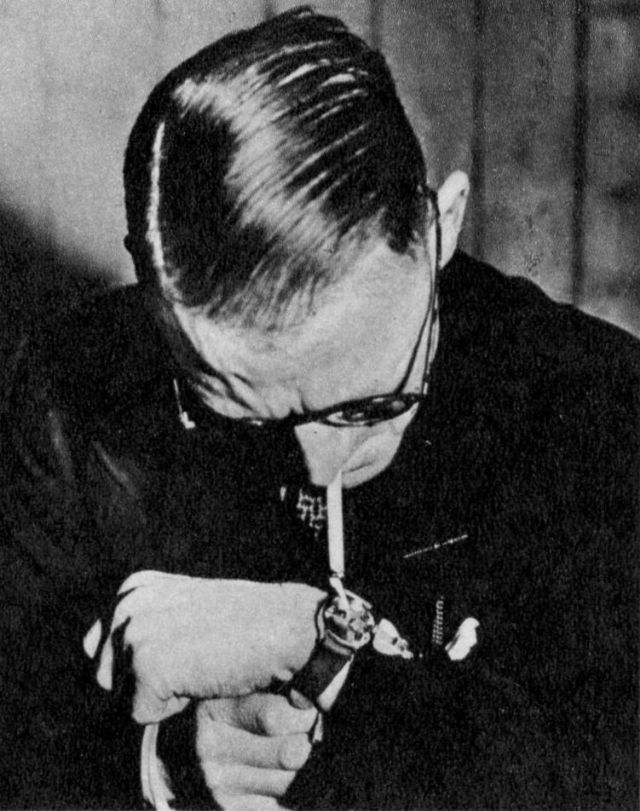

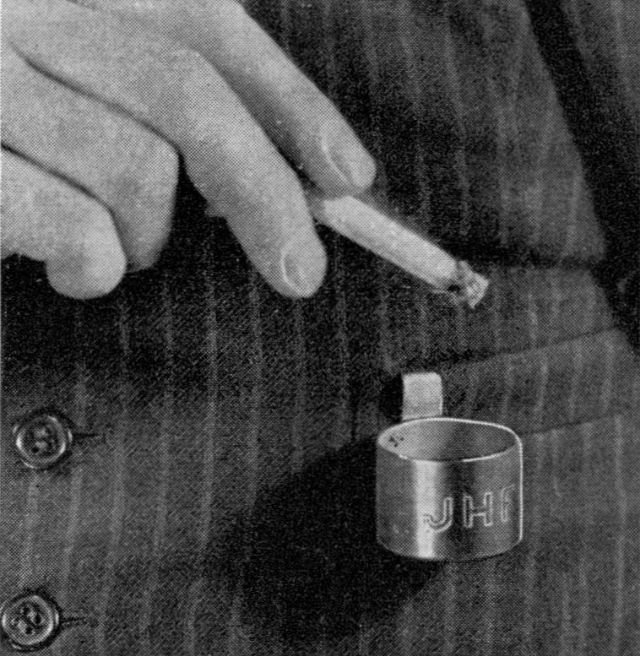

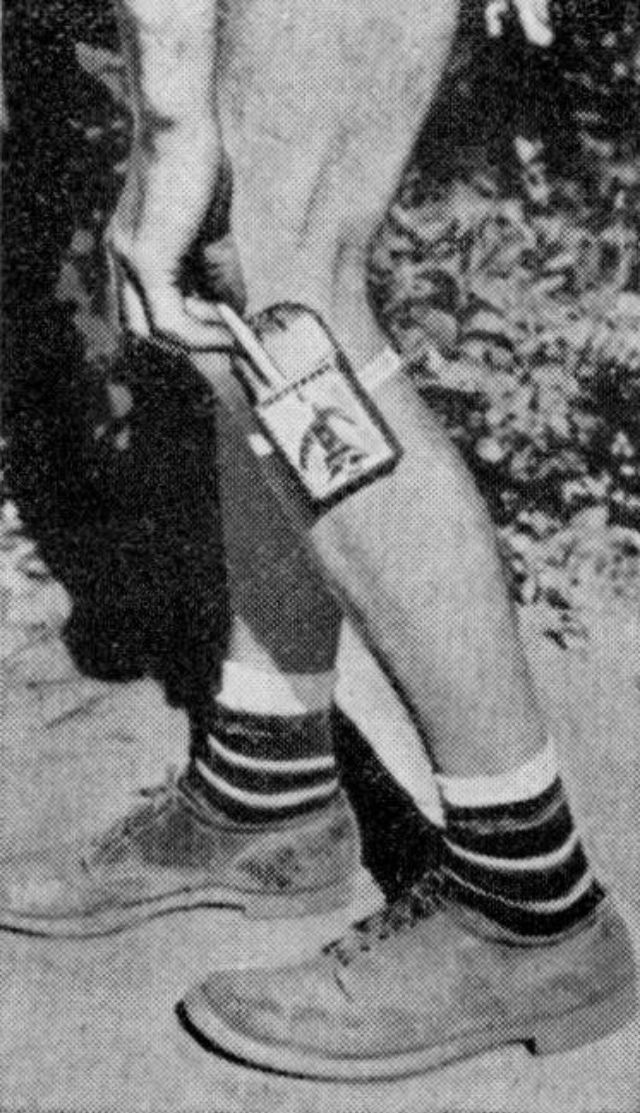

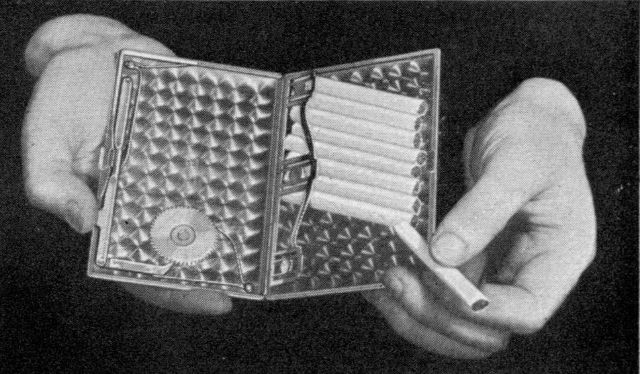

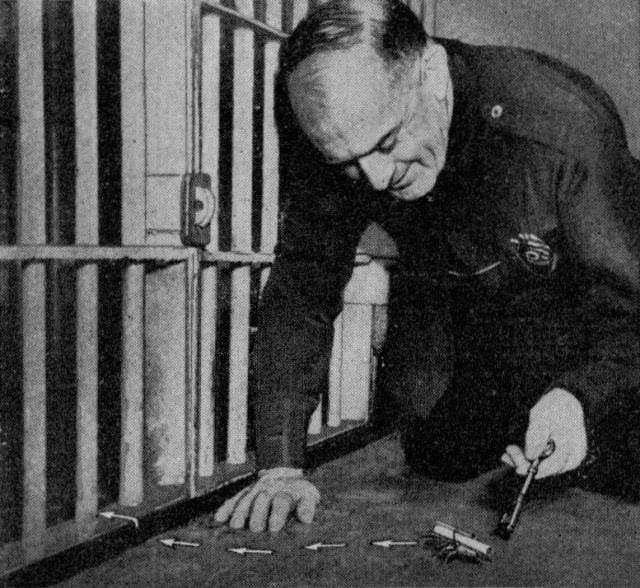

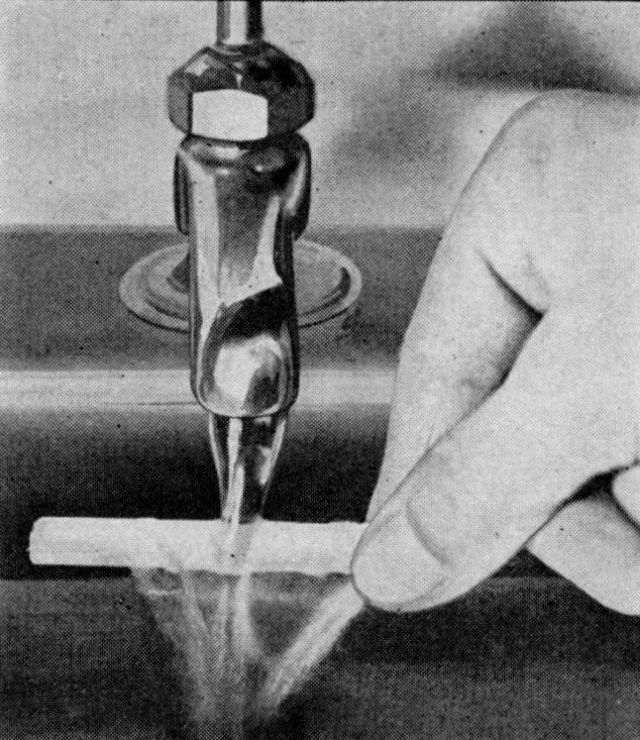

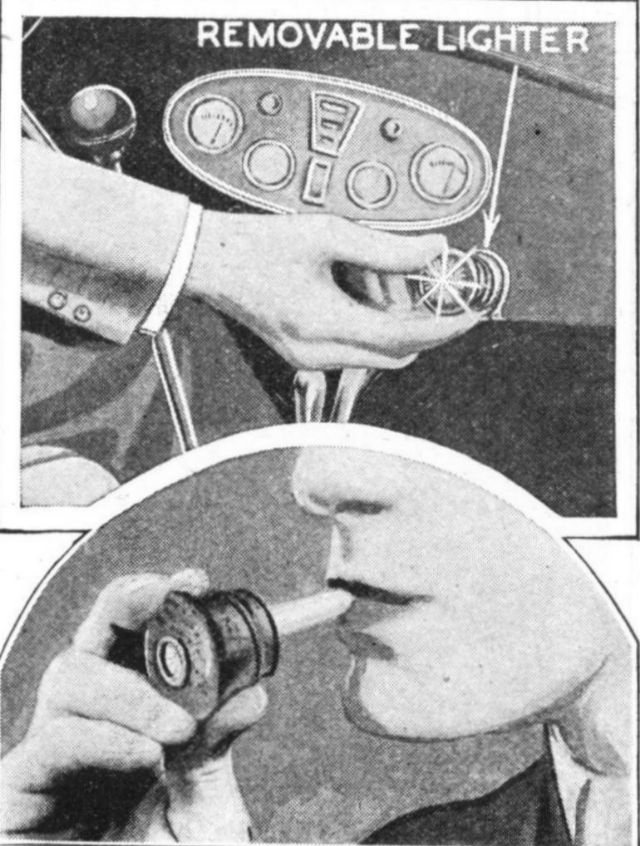

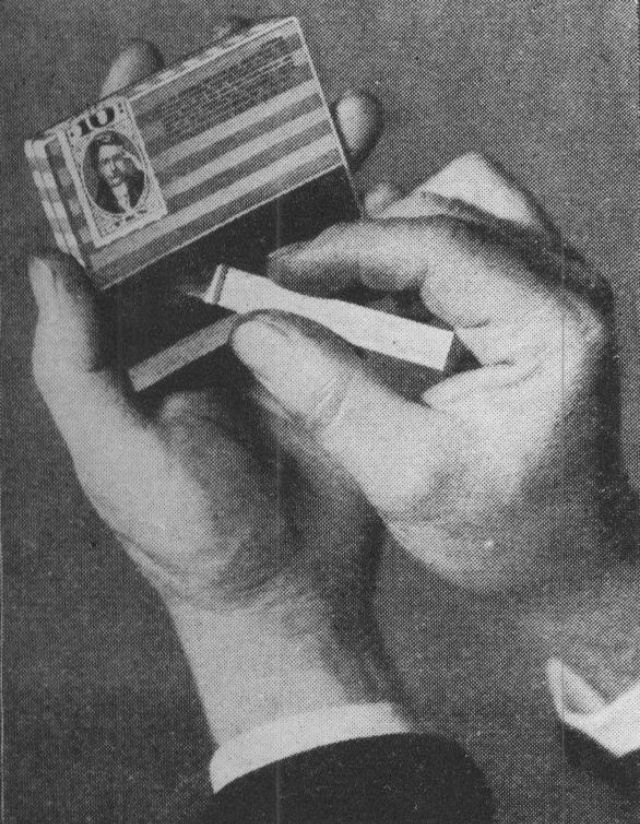

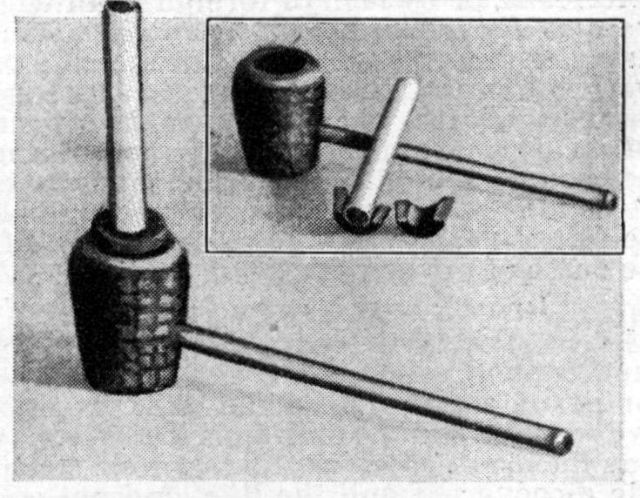

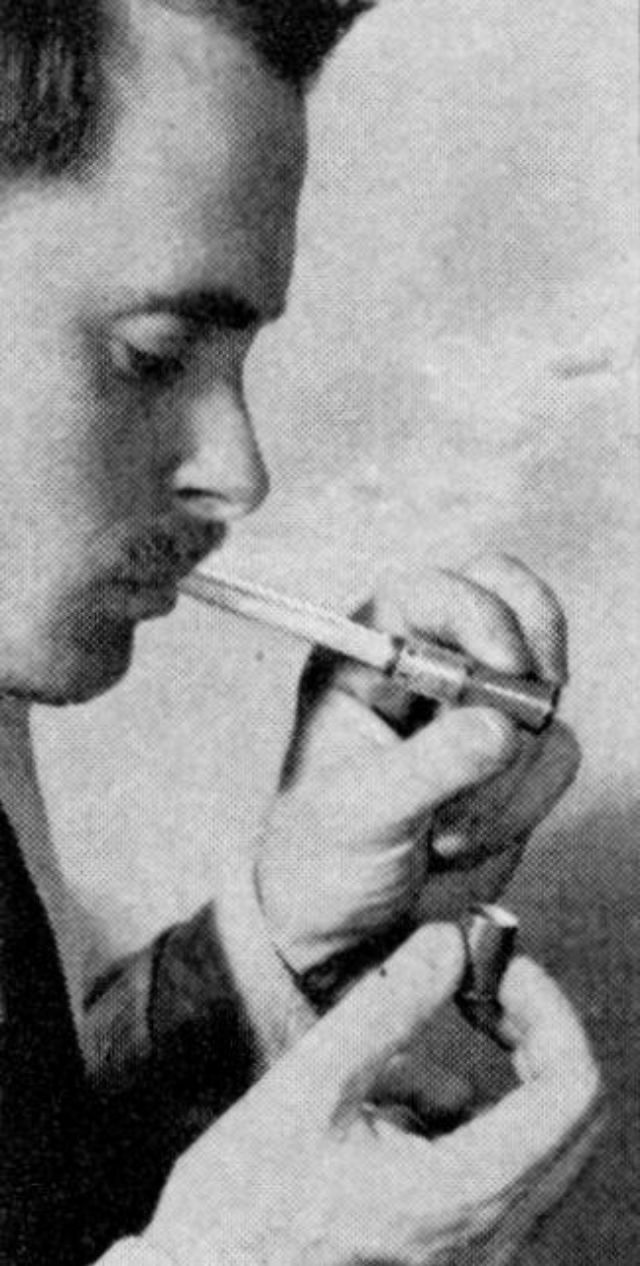

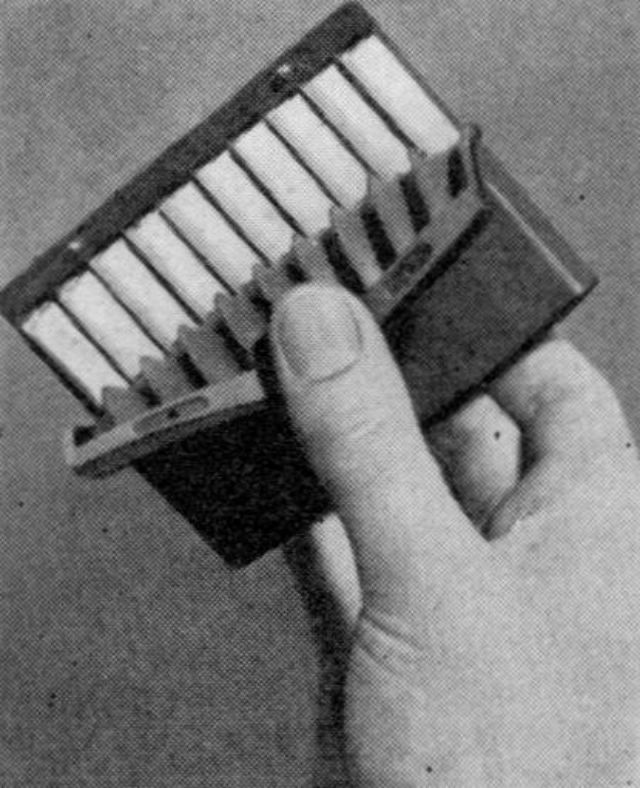

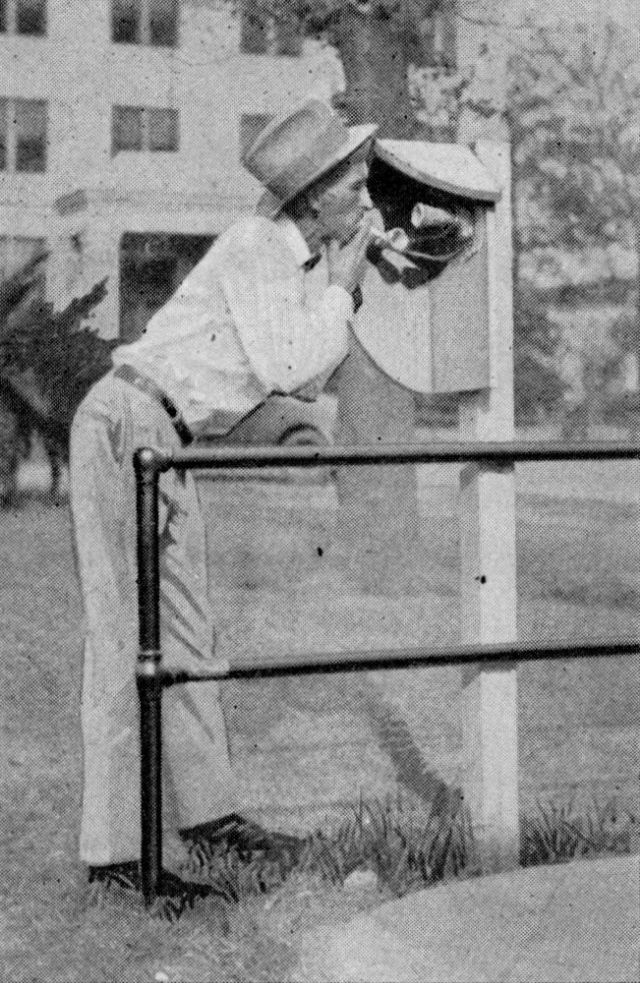

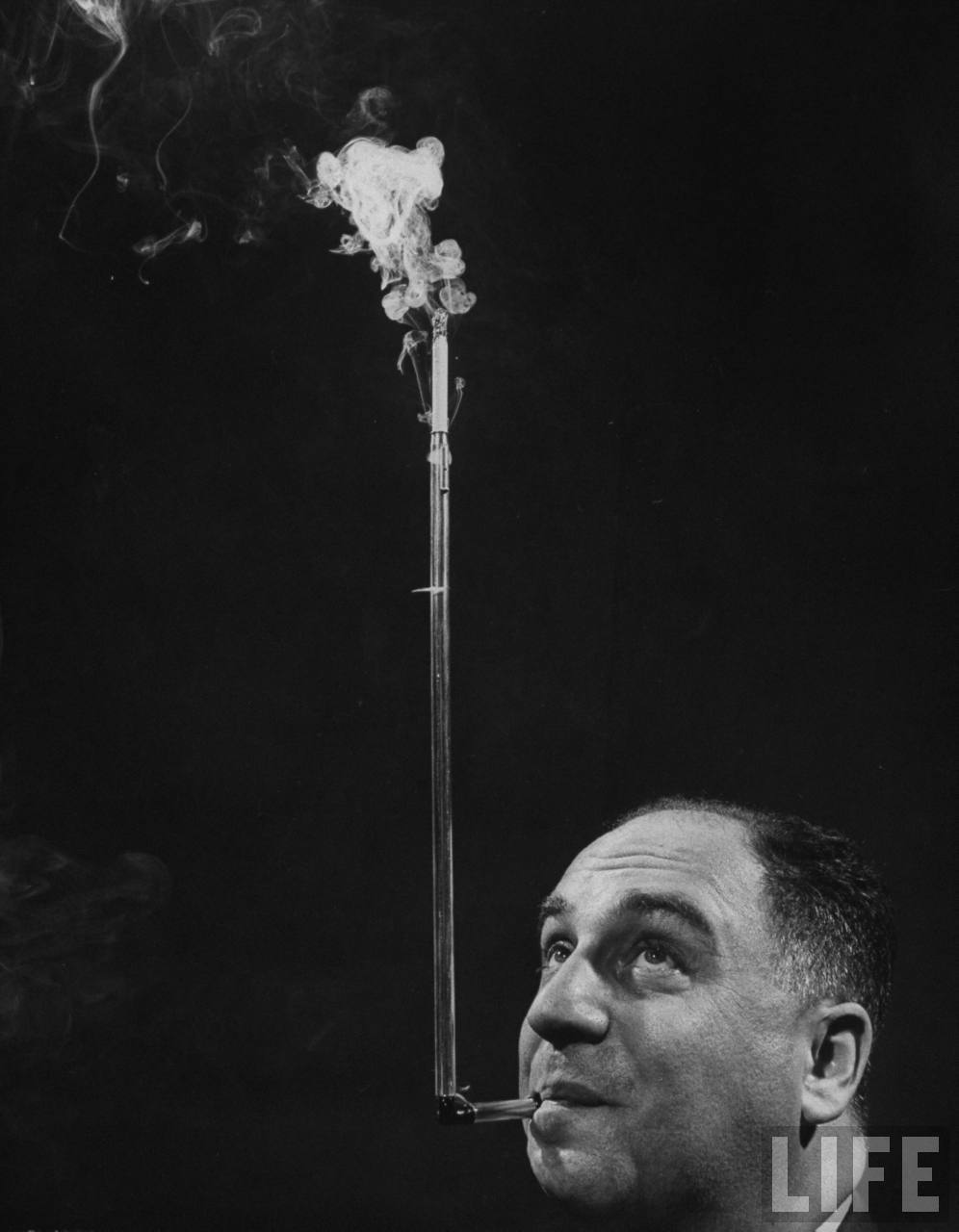

Inventors introduced and advertised several cigarette accessories, such as automated lighters, remote smoking apparatus, double-barrel cigarette holders, umbrella smoke holders, waterproof puffs, carry-on ashtrays, etc. Cigarette smoking grew rapidly in America in the early part of the twentieth century, following the invention of automatic cigarette rolling machines and the rise of advertising and promotion on an unprecedented scale. Cigarette use grew despite opposition from temperance advocates and religious leaders concerned that smoking would lead to alcohol abuse and narcotic drugs, especially among youth. During the first half of the century, however, neither the public nor most physicians recognized a significant health threat from smoking. With the end of Prohibition and the decline of the temperance movement, advertising in the 1930s and 1940s was defined by campaigns which often included explicit health claims, such as “They don’t get your wind” (Camel, 1935), “gentle on my throat” (Lucky Strike, 1937), “play safe with your throat” (Phillip Morris, 1941), and “Fresh as mountain air” (Old Gold, 1946). Smokers of Camels were even encouraged to smoke a cigarette between every course of a Thanksgiving meal–as an “aid to digestion.” Except for a brief period around the Great Depression, per capita cigarette consumption increased steadily until 1953, by which time 47% of American adults were smoking cigarettes and half of all physicians. In the early 1950s evidence implicating smoking as a cause of lung cancer began to appear more frequently in medical journals and the popular press. Cigarette sales declined in 1953 and the first part of 1954, but quickly rebounded as manufacturers rushed to introduce and market “filtered” cigarettes to allay health concerns. The emergence of the filter-tip cigarette was a direct response to the publicity given to evidence linking smoking and cancer, and consumers reacted by shifting over to the new designs. In 1952 filtered cigarettes accounted for less than 2% of sales; by 1957 this had grown to 40% and would surpass 60% by 1966. The advertised benefits of filters were illusory, however, given that smokers of filtered brands often inhaled as much or more tar, nicotine, and noxious gases as smokers of unfiltered cigarettes. Filters were not really even filters in any meaningful sense, since there was no such thing as “clean smoke.” The industry had recognized this as early as the 1930s, but smokers were led to believe they were safer. By 1957 the evidence implicating smoking as a causative factor in lung cancer had been established to a high degree of scientific certainty, leading to the first official statement from the US Public Health Service implicating smoking as a cause of lung cancer. The tobacco industry also took notice of the emerging evidence, but instead of acknowledging what they knew to be true, hired a public relations firm (in December 1953) to implement a massive campaign to challenge the evidence. Medical doctors and academic scholars were hired to defend the industry’s claim that the evidence was “merely statistical” or based only on “animal evidence”. The public relations campaign, which would extend for over 40 years, was designed with the goal of reassuring the public, especially current smokers, that the question of whether smoking caused harm was an “open controversy”. The 1964 report of the Surgeon General’s Advisory Committee marks the beginning of a significant shift in public attitudes about smoking. Declining adult per capita cigarette consumption after 1964 followed increasing public appreciation of the dangers of tobacco use, accompanied by increasing efforts to regulate the use, sale, and advertising of tobacco products. Since 1964 there has also been a dramatic shift in the public’s knowledge and attitudes about smoking. In the mid-1960s it was still common to see doctors, athletes, and radio, movie and TV celebrities smoking or advertising different cigarette brands, and cigarette companies were major sponsors of popular shows on all three television networks. The Federal Trade Commission in 1967 commented on how it was “impossible for Americans of almost any age to avoid cigarette advertising”, which is hardly surprising given the levels of money involved. In 2010, the US Surgeon General reported that from 1940 into 2005, an estimated $250 billion was spent in the U.S. on cigarette advertising (adjusted for inflation, in 2006 dollars). Many are inventions were devised to insure dry smoke, but it has remained for a clown appearing with a circus in England to solve the problem. An umbrella over the smoke keeps off the water and a spigot drains off excess moisture. Cigarettes that light themselves without matches have been made before, but this novelty in a new form has just been introduced by a San Francisco manufacturer. Ten cigarettes are packed in a box, each provided with a tip of yellow composition. Scratched like a safety match, upon a special surface of the box, a flare results that lights the cigarette. A strong wind does not interfere with the lighting, according to the maker. He claims his composition is free of objectionable taste in burning, overcoming the principal problem of other inventors who have sought self-lighting cigarettes. An “ammunition” hat designed with tuck in which are inserted twenty cigarettes, is proclaimed by stylists as the latest fad for co-eds. Wearing this hat, shown in the photo above, the co-ed needs no longer go through the awkward motions of searching through a handbag for her puffs. All she has to do is to reach up and pluck one from her hat. The cigarettes are arranged to appear like ornaments on the hat. The slots which hold the puffs are made extremely rigid so as to prevent breaking. To make a cigarette holder that filters and cools the smoke, procure a small size corncob and a close-grained cork. Trim the cork so that it fits tightly into the bowl with about 1/4 inch of the cork projecting to make removal of stubs easy. For a filter and cooler, place a small cotton wad and menthol crystals in the bowl. With a red hot iron burn a hole through the center of the cork to hold the cigarette. Then cut the cork in half, place the smoke between the corks, and insert it into the pipe. Smoking is coming to be such a convenient matter that it is a wonder any of us can resist becoming insatiable cigarette fiends. The latest device to ease the labor of lighting up a puff is an electric desk dispenser which delivers one cigarette at a time, fully lighted and ready to smoke. Shown in the accompanying photo above, the dispenser holds one package of cigarettes at a time and is operated by the easy pressure of the forefinger against a lever. The smoke, with its end aglow, pops out of a little aperture at the side. The dispenser is surprisingly small and is designed to take the place of individual holders and lighters occupying twice the space. Because a smoker often has a cigarette but no match with which to light it, an inventor has developed a self-lighting puff that eliminates the use of matches. The idea is unique in its field and should be received with favor by all tobacco users who have been caught in a similar predicament. The device consists of a container and its pack of specially prepared cigarettes. Each cigarette has an oxidized fiber ring added to the tip that ignites immediately, like an ordinary match, when the puff is rubbed on the side. No larger than a woman’s lipstick, a new mystery cigarette lighter works without flame or electricity. The smoker simply holds his cigarette against the porous top and inhales several times and this lights the smoke. The secret is that a blended fuel containing methyl alcohol is thus drawn through a porous pill containing platinum. Catalytic action, similar to that of platinum gas-stove lighters, causes the pill to glow and light the cigarette. Wind cannot interfere with the use of the lighter, which works if a cotton pad is kept saturated with fuel. An easily operated vending machine that sells one cigarette at a time and yet complies with the laws has been marketed for use in public places. The pufss are sold directly from the flat tins of fifty, and are made accessible to the buyer by the insertion of a penny in a slot. A new cigarette has a novel filter tip made of rolled, pleated paper. Besides protecting the smoker’s lips from the annoyance of loose tobacco ends, the rolled-in filter is said to provide cooler smoke. Equipped with a self-tilting mechanism, this ash tray makes it impossible for a cigarette to burn down so short that the weight of the over-hanging end causes the cigarette to over-balance and fall off the tray and burn the table or rug. If the cigarette is allowed to burn for any length of time while on the rest, its heat causes a spring within the tray to expand and tilt, thus dumping the burning butt into the tray. This tray in use eliminates not only the danger of damaging furniture as the result of forgotten cigarettes, but the possibility of fire from the same cause. Comfortable to carry, a new cigarette case of rubber is declared sufficiently flexible to conform to the body, but stiff enough to protect from damage the ten cigarettes it holds. To remove one, the elastic cover flap is drawn back as shown above. When released, it closes off its own accord. An electric cigarette lighter, shielded from the weather by a small roof, is an odd sight at a corner of a Beaumont, Texas, oil field. So dreaded a hazard is fire here that workmen are forbidden to carry matches. Violation of this rule is considered almost as serious an offense as it would be in a powder plant. To encourage its observance, the owners of the field installed the lighter, just outside the danger zone, for the convenience of employees who wished to smoke during the noon hour. As a result, the field boasts an enviable safety record. THE NOVEL cigarette case shown below contains not only smoking materials, but also a complete checkerboard and men. The white and black pieces are small pegs which fit into holes in the squares to prevent them from being lost. The driver drops a cigarette into a conventional opening and pushes a button located on the side. The button pops up to indicate that the cigarette is lit and ready to be smoked. The entire process can be done without taking one’s eyes off the road. (Photo credit and descriptions: Modern Mechanix’ blog / Article based on The Changing Public Image of Smoking in the United States: 1964–2014 by K. Michael Cummings and Robert N. Proctor / Other images from Wikimedia Commons and Flickr). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe