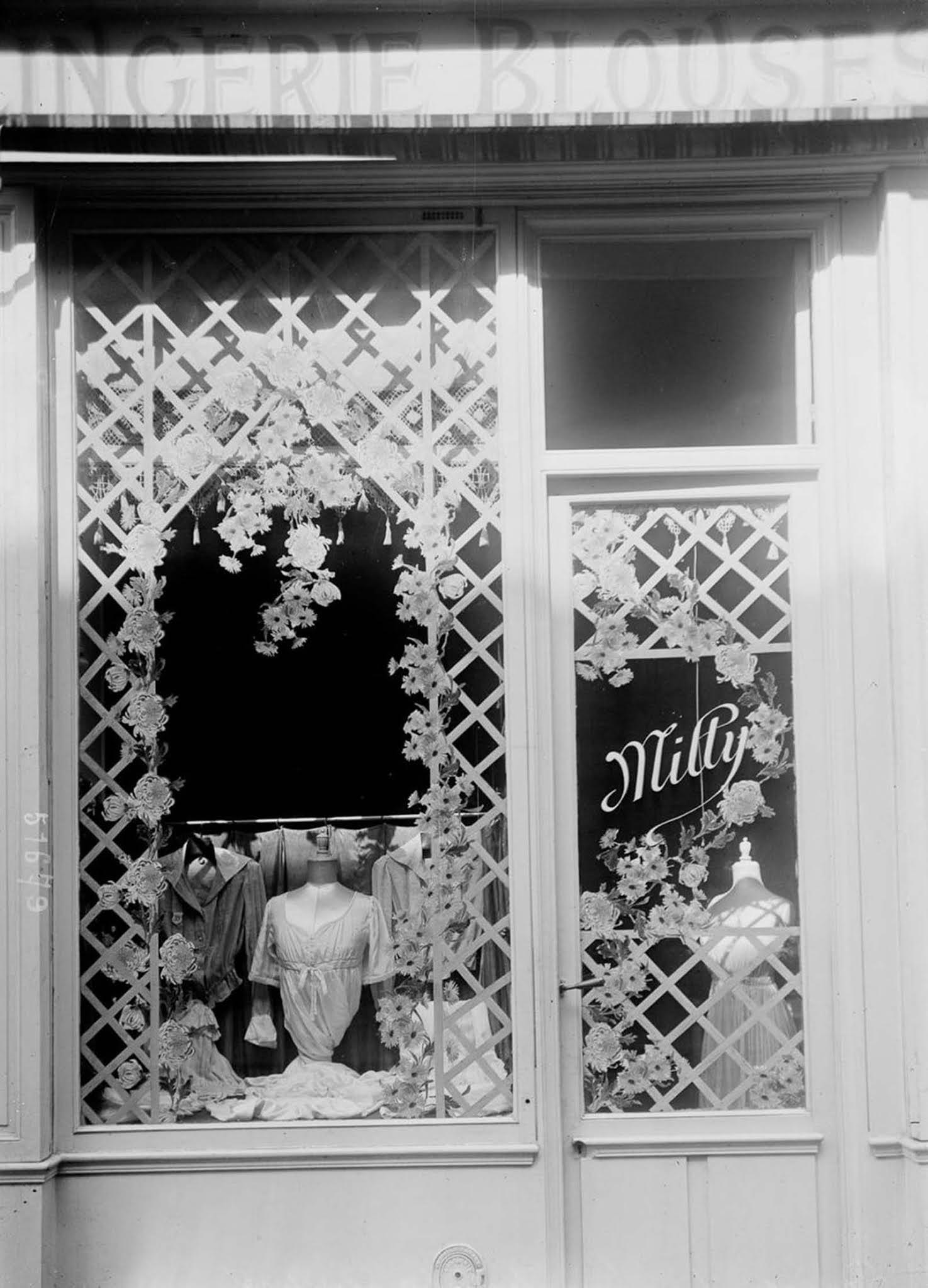

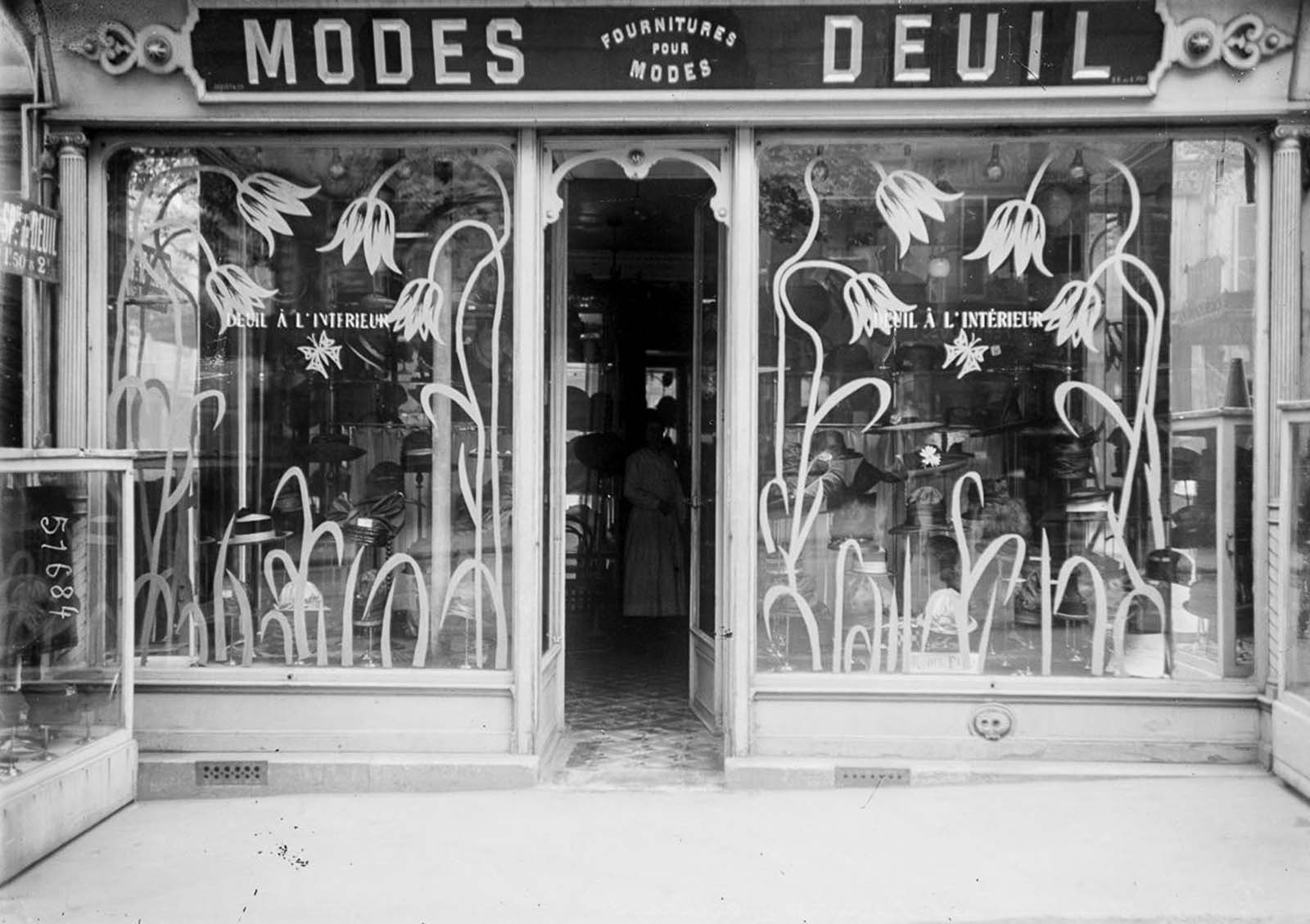

Once the war started, much of the city’s bustling life abruptly halted as men mobilized and shipped off to the frontlines. In their place, wives, daughters, sisters, and mothers filled the labor gap. Many shops closed, though those selling food and other daily provisions remained open. Several of Paris’ big hotels, devoid of guests and much of their staff, transformed into hospitals. In order to wreck France’s economy and military, reduce its population, and in short, cripple its morale as well as its ability to continue the war, the Germans bombed Paris without regard to the fact that most of the victims were civilians. The bombing succeeded in provoking just the right amount of terror; France’s minister of the interior could only keep government officials from fleeing Paris by threatening them with severe penalties. It was during this time that sandbags began to enter largely into the scenery of Paris. To protect its famous monuments from bombardment and shrapnel, the city’s population set up piles of sandbags, stored the important artwork in a safe location, removed the stained-glass windows from cathedrals and other buildings. Another creative protection method was reinforcing windows with lattices of masking tape which was never tested whether it really worked against the blast. Nevertheless, it offered some sort of psychological protection against the gloomy wartime backdrop. The city was regularly bombed by long-range German guns and Zeppelins. One of the most famous canons was called “The Paris Gun” which was specially built to shell Paris at a range, never before attained, of approximately 121 km (75 miles). The Paris Guns were moved to their emplacements near the German front lines on railway tracks and successively carried out an intermittent bombardment of Paris over a period of about 140 days, beginning in March 1918. The Paris Guns killed about 250 Parisians and wrecked a number of buildings, but they did not appreciably affect French civilian morale or the larger course of the war. The name Big Bertha, which was derisively applied to the guns by Parisians under bombardment from them, is more properly applied to the 420-millimeter howitzers used by the German army to batter Belgian forts in August 1914, at the start of the war.

(Photo credit: Biblioteque Nationale de France). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe