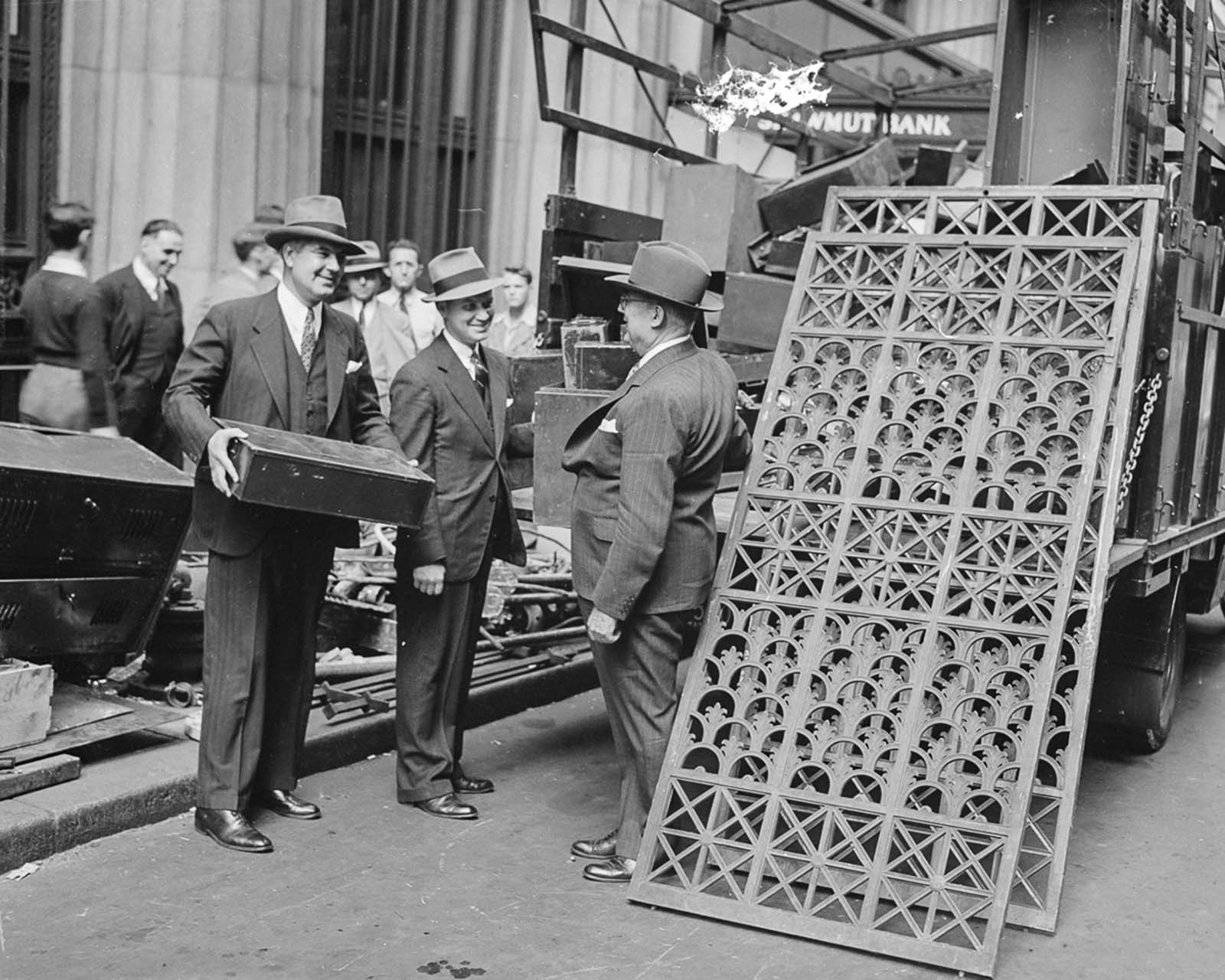

Citizens were asked to scour their homes and businesses for spare metal. From pots and pans to metal toys, to car bumpers, to farm equipment- any metal was considered valuable. Communities melted down Civil War cannons and tore down wrought iron fences, sacrificing their history for their future. When people came together to find scrap metal, these drives became larger community events that included performers, speeches, and games. In Lubbock, Texas, a bust of Hitler was erected as a target for patriotic citizens to hurl their unwanted items. Competitions were held to see which town, county, and state produced the most scrap, and the winners boasted of their feats. From June 15-30, 1942, the United States held a nationwide rubber drive. People brought in old or excess tires, raincoats, hot water bottles, boots, and floor mats. In exchange, they received a penny a pound. Although 450,000 tons of scrap rubber was collected, used rubber was found to be of poor quality. A paper drive in mid-1942 brought in so much paper that mills were inundated and actually called for a stop. However, by 1944 an acute paper shortage existed. The Boy Scouts and local schools organized regular paper drives, often coordinated with the tin can drives. The War Production Board started the Paper Troopers program, designed to sound like “paratroopers,” to involve schoolchildren in the effort. Most Americans viewed the scrap drives as their patriotic duty to contribute their time and their products. Historians, however, debate how necessary scrap drives were and whether or not they helped the United States defeat Germany, Italy, and Japan. While not all scrap materials proved useful, many did and provided a small but significant source of the material. Most importantly, these drives galvanized the Home Front and created a sense of patriotic unity.

(Photo credit: Leslie Jones / Boston Public Library). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe