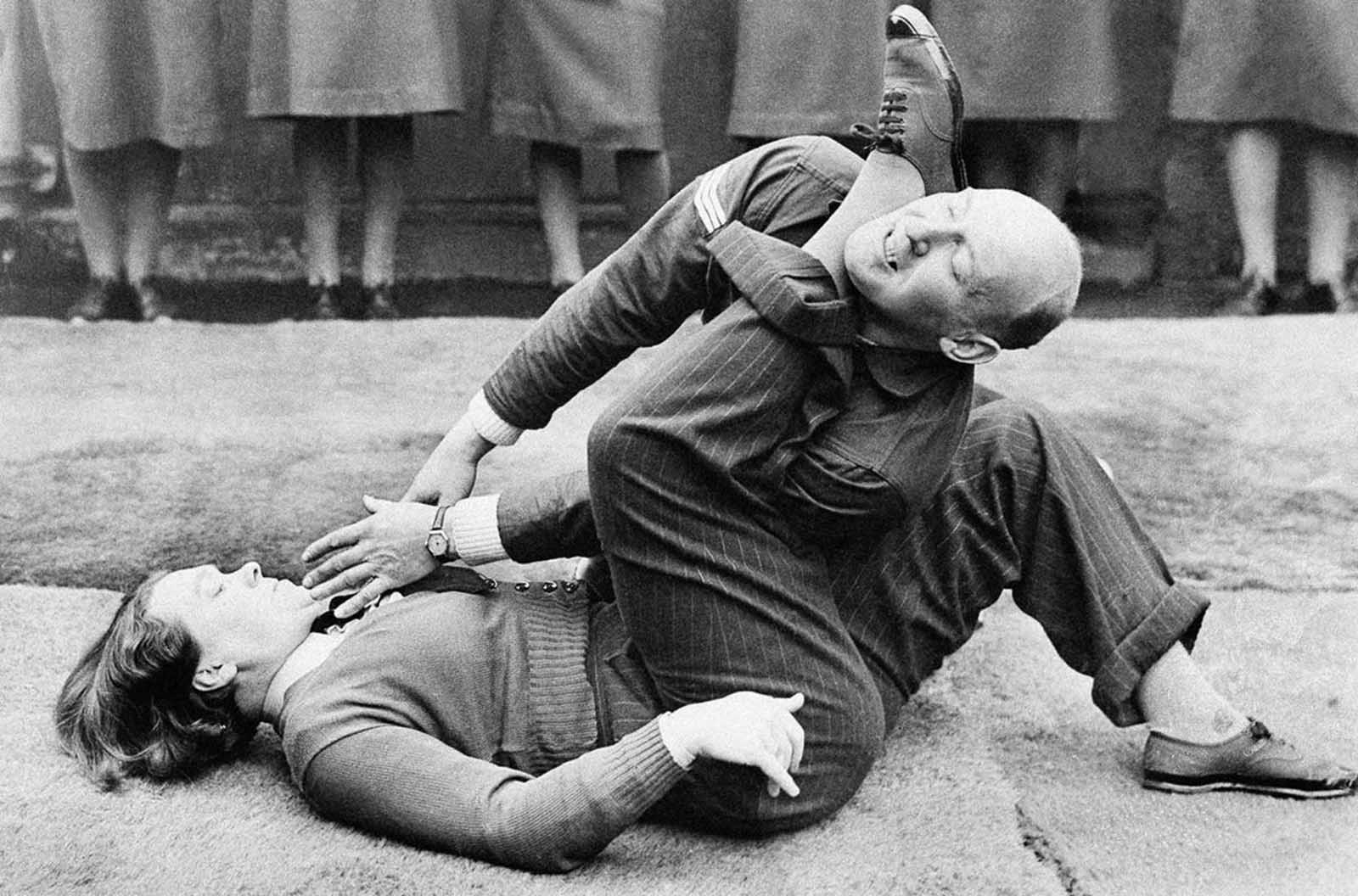

More than seven million women who had not been wage earners before the war joined eleven million women already in the American work force. Between 1941 and 1945, an untold number moved away from their hometowns to take advantage of wartime opportunities, but many more remained in place, organizing home front initiatives to conserve resources, to build morale, to raise funds, and to fill jobs left by men who entered military service. The U.S. government, together with the nation’s private sector, instructed women on many fronts and carefully scrutinized their responses to the wartime emergency. The foremost message to women—that their activities and sacrifices would be needed only “for the duration” of the war—was both a promise and an order, suggesting that the war and the opportunities it created would end simultaneously. Social mores were tested by the demands of war, allowing women to benefit from the shifts and make alterations of their own. Yet dominant gender norms provided ways to maintain social order amidst fast-paced change, and when some women challenged these norms, they faced harsh criticism. Race, class, sexuality, age, religion, education, and region of birth, among other factors, combined to limit opportunities for some women while expanding them for others. Several hundred thousand women served in combat roles, especially in anti-aircraft units. The U.S. decided not to use women in combat because public opinion would not tolerate it. However 400,000 women served in uniform in non-combat roles in the U.S. armed forces; 16 were killed by enemy fire. Many women served in the resistances of France, Italy, and Poland, and in the British SOE and American OSS which aided these. Other women, called comfort women, were forced into sexual slavery by the Imperial Japanese Army before and during World War II. The name “comfort women” is a translation of the Japanese euphemism and the similar Korean term wianbu is a euphemism for shōfu whose meaning is “prostitute(s)”. Estimates vary as to how many women were involved, with numbers ranging from as low as 20,000 to as high as 360,000 to 410,000, in Chinese sources; the exact numbers are still being researched and debated. Many of the women were from occupied countries, including Korea, China, and the Philippines, although women from Burma, Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia, Taiwan (then a Japanese dependency), Indonesia (then the Dutch East Indies), East Timor (then Portuguese Timor),and other Japanese-occupied territories were used for military “comfort stations”. Stations were located in Japan, China, the Philippines, Indonesia, then Malaya, Thailand, Burma, New Guinea, Hong Kong, Macau, and French Indochina.A smaller number of women of European origin from the Netherlands and Australia were also involved. According to testimony, young women from countries in Imperial Japanese custody were abducted from their homes. In many cases, women were also lured with promises of work in factories or restaurants; once recruited, the women were incarcerated in comfort stations in foreign lands. In Germany – On the eve of war 14.6 million German women were working, with 51% of women of working age (16–60 years old) in the workforce. Nearly six million were doing farm work, as Germany’s agricultural economy was dominated by small family farms. 2.7 million worked in industry. When the German economy was mobilized for war it paradoxically led to a drop in female work participation, reaching a low of 41% before gradually climbing back to over 50% again. This still compares favorably with the UK and the USA, both playing catchup, with Britain achieving a participation rate of 41% of women of working age in 1944. However, in terms of women employed in war work, British and German female participation rates were nearly equal by 1944, with the United States still lagging. The difficulties the Third Reich faced in increasing the size of the work force was mitigated by reallocating labor to work that supported the war effort. High wages in war industries attracted hundreds of thousands, freeing up men for military duties. Prisoners of war were also employed as farmhands, freeing up women for other work. The Third Reich had many roles for women, including combat. The SS-Helferinnen were regarded as part of the SS if they had undergone training at a Reichsschule SS but all other female workers were regarded as being contracted to the SS and chosen largely from Nazi concentration camps. Women also served in auxiliary units in the navy (Kriegshelferinnen), air force (Luftnachrichtenhelferinnen) and army (Nachrichtenhelferin). Hundreds of women auxiliaries (Aufseherin) served for the SS in the camps, the majority of which were at Ravensbrück. In 1944-45 more than 500,000 women were volunteer uniformed auxiliaries in the German armed forces (Wehrmacht). About the same number served in civil aerial defense, 400,000 volunteered as nurses, and many more replaced drafted men in the wartime economy. In the Luftwaffe they served in combat roles helping to operate the anti—aircraft systems that shot down Allied bombers. By 1945, German women were holding 85% of the billets as clericals, accountants, interpreters, laboratory workers, and administrative workers, together with half of the clerical and junior administrative posts in high-level field headquarters. Germany had a very large and well organized nursing service, with four main organizations, one for Catholics, one for Protestants, the secular DRK (Red Cross) and the “Brown Nurses,” for committed Nazi women. Military nursing was primarily handled by the DRK, which came under partial Nazi control. Frontline medical services were provided by male medics and doctors. Red Cross nurses served widely within the military medical services, staffing the hospitals that perforce were close to the front lines and at risk of bombing attacks. Two dozen were awarded the Iron Cross for heroism under fire. In Italy women joined the anti-fascist resistance, and also served in the fascist army of Mussolini’s rump state that formed in 1943. They did not serve in the main Italian army. Some 35,000 women (and 170,000 men) joined in the Resistance. However the women ‘staffetta’ were used only as auxiliary support and were not allowed in senior ranks. Most did cooking and laundry duty. Some were guides, messengers, and couriers near the front lines. A few were attached to small attack groups of five or six men engaged in sabotage. Some all-female units, engaged in civilian and political action. The Germans aggressively tried to suppress them, sending 5000 to prison, deporting 3000 to Germany. About 650 died in combat or by execution. On a much larger scale, non-military auxiliaries of the Catholic Centro Italiano Femminile (CIF) and the leftist Unione Donne Italiane (UDI) were new organizations that gave women political legitimacy after the war. Mussolini’s Salo Republic, a puppet state of the Germans, gave their women roles as “birthing machines” and as noncombatants in paramilitary units and police formations (Servizio Ausiliario Femminile). The commander was the brigadier general Piera Gatteschi Fondelli. The Soviet Union mobilized women at an early stage of the war, integrating them into the main army units, and not using the “auxiliary” status. More than 800,000 women served in the Soviet Armed Forces during the war, which is roughly 3 percent of total military personnel, mostly as medics. About 300,000 served in anti-aircraft units and performed all functions in the batteries—including firing the guns. A small number were combat flyers in the Air Force, forming 3 bomber wings and joining into other wings. Women saw also combat in infantry and armored units, and female snipers became famous after commander Lyudmila Pavlichenko made a record killing 309 nazis (mostly officers and enemy snipers). Throughout World War II, women appeared in Soviet war propaganda in various capacities. Between 1939 and 1941, wary of German militarism and expansionism, Soviet propaganda encouraged women to undertake paramilitary civil defense training. After the German invasion in 1941, propaganda portrayed women participating in war-related industries, in the medical sector, or in partisan units. Before the severe manpower shortages of 1942, women were prohibited from serving in combat positions, and Soviet propaganda celebrated women’s contributions on the home front. In March 1942, when the People’s Commissariat of Defense began enlisting women to replace male casualties in some combat roles, Soviet propaganda began honoring individual war heroines. The USSR utilized propaganda celebrating heroic servicewomen to recruit more female soldiers. As a result, the state directed these stories only towards female workers that could be spared for front line service. Magazines for women in industrial jobs, such as Rabotnitsa, called upon readers to fulfill their patriotic duty and take up arms like other brave female soldiers. Since agricultural work was vital for the war effort, articles for peasant women addressed females only as partisans. Media coverage ignored the broader contribution of female soldiers and concealed the number of women in combat positions. As the number of female soldiers increased, state media could no longer ignore their contribution to the war effort. When designated for a broader audience, propaganda emphasized the femininity of female soldiers, who were portrayed as pretty, energetic, and spirited. These women kept culture alive in the male dominated units, encouraging cleanliness among their male comrades. Propaganda represented older female soldiers as motherly figures, caring for the male soldiers, while younger women assumed a sisterly image. In this context, Soviet propaganda depicted the armed forces as a family, courageously defending the motherland against the Fascist invasion. When Britain went to war, as before in World War I, previously forbidden job opportunities opened up for women. Women were called into the factories to create the weapons that were used on the battlefield. Women took on the responsibility of managing the home and became the heroines of the home front. According to Carruthers, this industrial employment of women significantly raised women’s self-esteem as it allowed them to carry out their full potential and do their part in the war. During the war, women’s normative roles of “house wife” transformed into a patriotic duty. As Carruther’s put it, the housewife has become a heroine in the defeat of Hitler. The roles of women shifting from domestic to masculine and dangerous jobs in the workforce made for important changes in workplace structure and society. During the Second World War, society had specific ideals for the jobs in which both women and men participated in. When women began to enter into the masculine workforce and munitions industries previously dominated by men, women’s segregation began to diminish. Increasing numbers of women were forced into industry jobs between 1940-1943. As surveyed by the Ministry of Labour, the percentage of women in industrial jobs went from 19.75 percent to 27 percent from 1938-1945. It was very difficult for women to spend their days in factories, and then come home to their domestic chores and care-giving, and as a result, many women were unable to hold their jobs in the workplace. Britain underwent a labour shortage where an estimated 1.5 million people were needed for the armed forces, and an additional 775,000 for munitions and other services in 1942. It was during this ‘labour famine’ that propaganda aimed to induce people to join the labor force and do their bit in the war. Women were the target audience in the various forms of propaganda because they were paid substantially less than men. It was of no concern whether women were filling the same jobs that men previously held. Even if women were replacing jobs with the same skill level as a man, they were still paid significantly less due to their gender. In the engineering industry alone, the number of skilled and semi-skilled female workers increased from 75 percent to 85 percent from 1940-1942. According to Gazeley, even though women were paid less than men, it is clear that women engaging in war work and taking on jobs preserved by men reduced industrial segregation. In Britain, women were essential to the war effort. The contribution by civilian men and women to the British war effort was acknowledged with the use of the words “Home Front” to describe the battles that were being fought on a domestic level with rationing, recycling, and war work, such as in munitions factories and farms and men were thus released into the military. Women were also recruited to work on the canals, transporting coal and munitions by barge across the UK via the inland waterways. These became known as the ‘Idle Women’, initially, an insult derived from the initials IW, standing for Inland Waterways, which they wore on their badges, but the term was soon adopted by the women themselves. Many women served with the Women’s Auxiliary Fire Service, the Women’s Auxiliary Police Corps and in the Air Raid Precautions (later Civil Defence) services. Others did voluntary welfare work with Women’s Voluntary Service for Civil Defence and the salvation Army. Women were “drafted” in the sense that they were conscripted into war work by the Ministry of Labour, including non-combat jobs in the military, such as the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS or “Wrens”), the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF or “Waffs”) and the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS). Auxiliary services such as the Air Transport Auxiliary also recruited women. In the early stages of the war such services relied exclusively on volunteers, however by 1941 conscription was extended to women for the first time in British history and around 600,000 women were recruited into these three organizations. In these organizations, women performed a wide range of jobs in support of the Army, Royal Air Force (RAF) and Royal Navy both overseas and at home. These jobs ranged from traditionally feminine roles like cook, clerk and telephonist to more traditionally masculine duties like mechanic, armourer, searchlight, and anti- aircraft instrument operator. British women were not drafted into combat units, but could volunteer for combat duty in anti-aircraft units, which shot down German planes and V-1 missiles. Civilian women joined the Special Operations Executive (SOE), which used them in high-danger roles as secret agents and underground radio operators in Nazi-occupied Europe. (Photo credit: AP / Library of Congress). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe