The son of Besarion Jughashvili, a cobbler, and Ketevan Geladze, a washerwoman, Joseph was a frail child. At age 7, he contracted smallpox, leaving his face scarred. A few years later he was injured in a carriage accident which left his arm slightly deformed (some accounts state his arm trouble was a result of blood poisoning from the injury). Stalin always felt unfairly treated by life, and thus developed a strong, romanticized desire for greatness and respect, combined with a shrewd streak of calculating cold-heartedness towards those who had maligned him. He always felt a sense of inferiority before educated intellectuals and particularly distrusted them. Sent by his mother to the seminary in Tiflis (now Tbilisi), the capital of Georgia, to study to become a priest, the young Stalin never completed his education and was instead soon completely drawn into the city’s active revolutionary circles. Never a fiery intellectual polemicist or orators like Lenin or Trotsky, Stalin specialized in the humdrum nuts and bolts of revolutionary activity, risking arrest every day by helping organize workers, distributing illegal literature, and robbing trains to support the cause, while Lenin and his bookish friends lived safely abroad and wrote clever articles about the plight of the Russian working class. Although Lenin found Stalin’s boorishness offensive at times, he valued his loyalty and appointed him after the Revolution to various low-priority leadership positions in the new Soviet government. In 1922, Stalin was appointed to another such post, as General Secretary of the Communist Party’s Central Committee. Stalin understood that “cadres are everything”: if you control the personnel, you control the organization. He shrewdly used his new position to consolidate power in exactly this way–by controlling all appointments, setting agendas, and moving around Party staff in such a way that eventually everyone who counted for anything owed their position to him. By the time the Party’s intellectual core realized what had happened, it was too late–Stalin had his (mostly mediocre) people in place, while Lenin, the only person with the moral authority to challenge him, was on his deathbed and incapable of speech after a series of strokes, and besides, Stalin even controlled who had access to the leader. Driven by his own sense of inferiority, which he projected onto his country as a whole, Stalin pursued an economic policy of mobilizing the entire country to achieve the goal of rapid industrialization, so that it could stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the Capitalist powers. To this end, he forcefully collectivized agriculture (one of the Bolsheviks’ key policy stances in 1917 was to give the land to the peasants; collectivization took it back from them and effectively reduced them to the status of serfs again), instituted the Five-Year Plans to coordinate all investment and production in the country, and undertook a massive program of building heavy industry. Although the Soviet Union boasted that its economy was booming while the Capitalist world was experiencing the Great Depression, and its industrialization drive did succeed in rapidly creating an industrial infrastructure where there once had been none, the fact is that all this was done at an exorbitant cost in human lives. Measures such as the violent expropriation of the harvest by the government, the forced resettlement and murder of the most successful peasants as counterrevolutionary elements, and the discovery of a source of cheap labor through the arrest of millions of innocent citizens led to countless millions of deaths from the worst man-made famine in human history and in the camps of the Gulag.

Interesting facts about Stalin

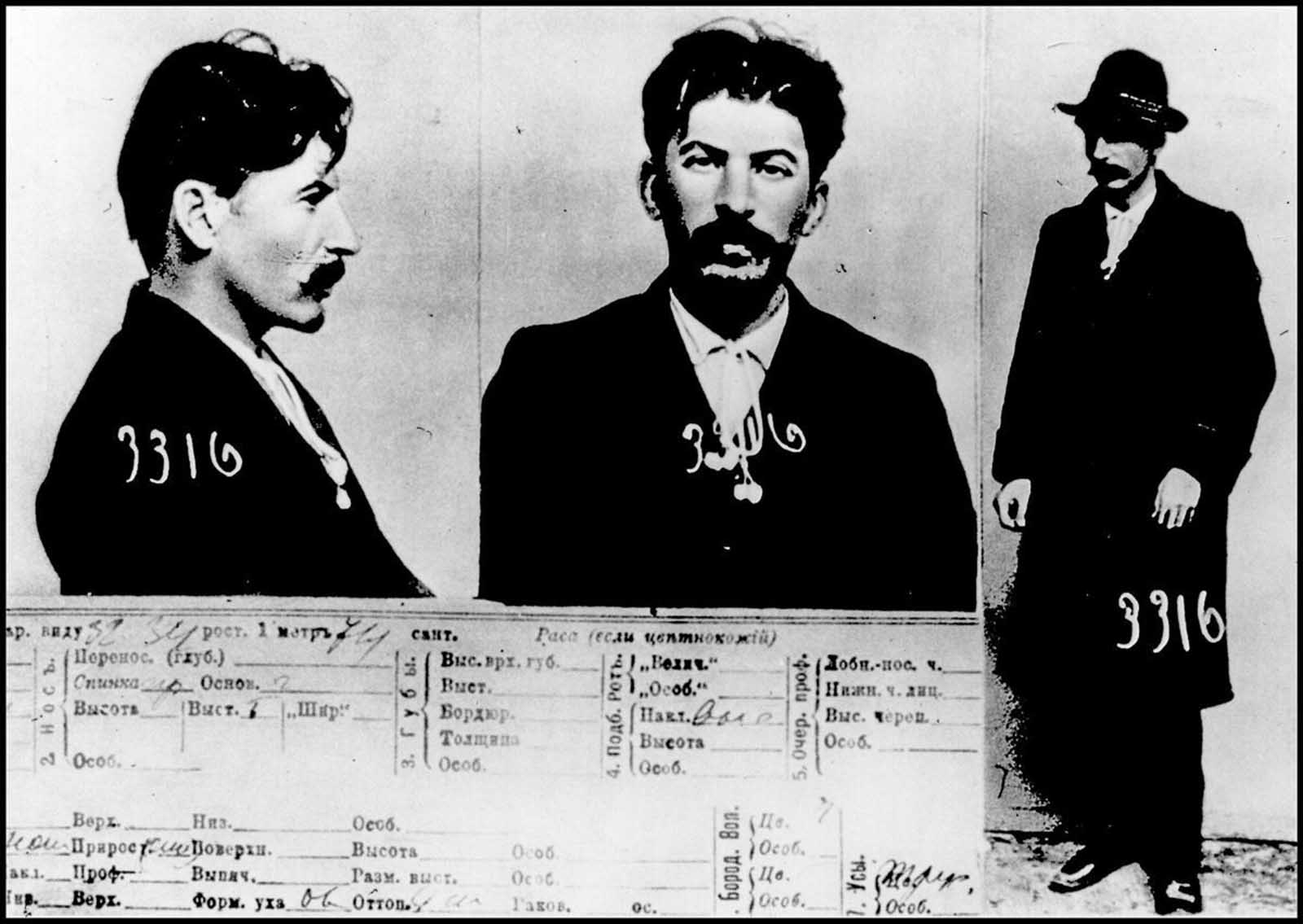

Like many outlaws, Stalin used many aliases throughout his revolutionary career, of which “Stalin” was only the last. During his education in Tiflis, he picked up the nickname “Koba”, after the Robin Hood-like protagonist from the 1883 novel The Patricide by Alexander Kazbegi. This became his favorite nickname throughout his revolutionary life. Among his friends he was sometimes known by his childhood nickname “Soso” – a Georgian diminutive form of the name Ioseb (Joseph). An article in the newspaper Pravda in 1988 claimed the word derives from the Old Georgian for “steel” which might be the reason for his adoption of the name Stalin. Сталин (“Stalin”) is derived from combining the Russian сталь (“stal”), “steel”, with the possessive suffix -ин (“-in”), a formula used by many other Bolsheviks, including Lenin. For a long time, Stalin’s date of birth was falsified. Although there is an inconsistency among published sources about Stalin’s year and date of birth, Iosif Dzhugashvili is found in the records of the Uspensky Church in Gori, Georgia as born on 18 December (Old Style: 6 December) 1878. As late as 1921, Stalin himself listed his birthday as 18 December 1878 in a curriculum vitae in his own handwriting. However, after his coming to power in 1922, Stalin changed the date to 21 December 1879. That became the day his birthday was celebrated in the Soviet Union. When Stalin achieved prominence in the communist regime in the 1920s, his mother was installed in a palace in the Caucasus, formerly used by the tsar’s viceroy. Stalin wrote letters to Keke occasionally. These letters were affectionate and upbeat, but short; it took him an excessively long time to write them because it had become difficult for him to write in Georgian (the only language his mother understood). N. Kipshidze, a doctor who treated Keke in her old age, recalled that when Stalin visited his mother in October 1935, he asked her: “Why did you beat me so hard?” “That’s why you turned out so well”, Keke answered. In return, his mother asked him: “Joseph – who exactly are you now?” “Do you remember the tsar? Well, I’m like a tsar”, replied Stalin. “You’d have done better to have become a priest” was his mother’s retort. Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe